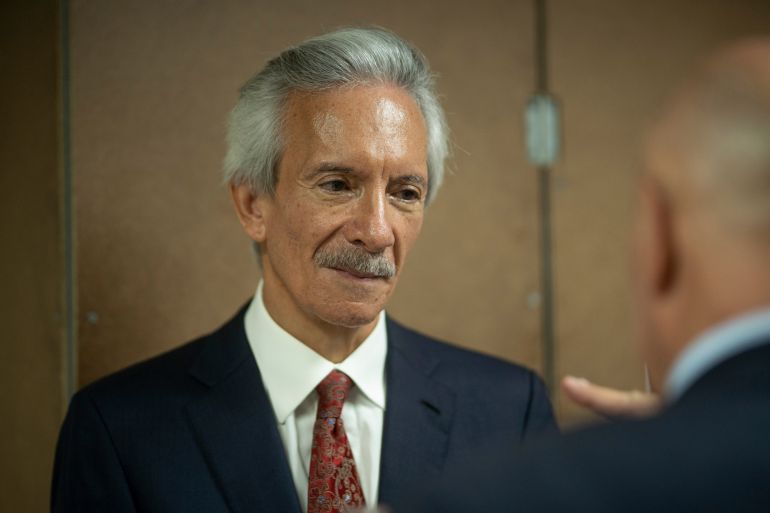

Critics have denounced the case against investigative journalist Jose Ruben Zamora as an attack on press freedom.

By Jeff Abbott

Published On 14 Jun 2023

An award-winning journalist in Guatemala has been convicted on criminal charges, in what human rights observers call yet another blow to press freedom and democracy in the Central American country.

José Rubén Zamora, a 66-year-old journalist and newspaper founder, was sentenced to six years in prison for money laundering.

“They treated us like criminals,” he said of the authorities who pursued the case. “They destroyed evidence.”

In announcing Wednesday’s verdict, the court in Guatemala City claimed Zamora had “harmed the Guatemalan economy”. The public prosecutor’s office had sought a 40-year sentence in the case.

Zamora, however, was acquitted on charges of blackmail and influence peddling.

The journalist, known for exposing corruption in Guatemala, still faces two other criminal cases, one pertaining to signatures on customs documents that did not match. That case was filed just days ahead of the sentencing.

The trial that concluded on Wednesday lasted only 11 sessions — held over 20 days — and has generated widespread concern and condemnation.

“My father is innocent,” the journalist’s son Jose Zamora told Al Jazeera ahead of Wednesday’s conviction.

“The [Guatemalan] state has kidnapped him,” he said. “They have subjected him, within this fabricated case, to a process that has been totally a violation of his due process.”

While the public prosecutor’s office has long maintained the case against Zamora was not about his journalism, critics say the accusations and rapid nature of the trial suggest otherwise.

The case stems from allegations made by Ronald Garcia Navarijo, a former banker accused of corruption, about a deposit of $38,000 that Zamora allegedly asked someone to make on his behalf, as part of a money-laundering scheme.

The Salvadoran newspaper El Faro reported that prosecutors prepared the case against Zamora within 72 hours of receiving the accusation.

Zamora was arrested in July 2022 and kept in pre-trial detention without being able to make his first appearance before the judge for nearly two weeks.

Other irregularities occurred throughout the trial, including Zamora being forced to change lawyers eight times, with at least four of his lawyers facing criminal charges related to the case.

Zamora and the newspaper he founded in 1996, El Periodico, have long worked to expose government misconduct. The paper has played a key part in uncovering alleged corruption in the current administration of President Alejandro Giammattei, publishing over 120 investigations into the government since January 2020.

But El Periodico was forced to close on May 15 amid the fallout from the Zamora case. Its journalists were investigated, and the newsroom had been targeted multiple times in recent years for tax audits.

In a statement, El Periodico’s leadership blamed “persecution” for shuttering the newsroom, as well as “the harassment of our advertisers”. Both Zamora’s case and El Periodico’s closure have raised concerns in the international community.

“They’re using all these tools to basically put [Zamora] out of business,” Carlos Martinez de la Serna, programme director with the US-based Committee to Protect Journalists, told Al Jazeera.

“[This is] sending a very chilling message to journalists — that basically reporting on corruption is a crime,” he said.

Attacks on press freedom

As the case against Zamora comes to a close, another case against journalists from El Periodico is set to begin.

In February, a judge authorised the investigation of nine journalists and columnists from El Periodico on charges of “conspiracy to obstruct justice”, following a request from the lead prosecutor in Zamora’s case. The charges stem from the publishing of stories critical of the legal proceedings against Zamora.

On June 5, the public prosecutor’s office officially requested all the stories published since July by the journalists and columnists in the case.

But the persecution against journalists extends beyond El Periodico’s newsroom, according to observers.

“The press is being harassed at the level of exposure of Jose Ruben Zamora, as well as other low-profile journalists and even community journalists,” Renzo Rosal, a political scientist at Guatemala’s Landivar University, told Al Jazeera.

“Journalists who carry out their work in the interior of the country are victims of the same logic: the logic of persecution, the logic of criminalisation, so that no one investigates anything,” he explained.

Critics say the criminalisation of journalists has become further entrenched since President Giammattei took the oath of office in 2020. A number of renowned journalists have been forced into exile, while others have faced criminal charges and threats.

For example, Anastasia Mejía, a community journalist in Joyabaj, Quiche, was arrested in 2020 on charges of sedition and arson following her coverage of protests against the mayor of the largely Indigenous municipality in Guatemala’s western highlands. The charges were dropped a year after she was first accused.

In another case from 2022, Carlos Choc, a community journalist from the eastern municipality of El Estor, faced the criminal charge of “instigation to commit a crime” following his coverage of anti-mining protests.

Eventually, Choc was exonerated, but the threats against journalists in El Estor remain, as police continue to intimidate other journalists working in the area.

The verdict in the Zamora case comes within days of Guatemala’s general election on June 25, which has likewise been plagued by controversy.

The country’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal has ruled to exclude three presidential candidates from the race on charges of noncompliance with the country’s election laws. Those disqualifications — which targeted at least one frontrunner — have raised questions about the fairness of the elections and Guatemala’s democratic institutions.

“Today the elections are another indicator of serious democratic erosion,” Rosal says.

Human rights observers have warned that Guatemala has recently seen a sharp rollback of its democracy and its anti-corruption efforts, even beyond the upcoming elections.

Nearly four years ago, the administration of former President Jimmy Morales oversaw the closure of the International Commission Against Impunity (CICIG), a United Nations-backed initiative to address crime and corruption that enjoyed public support of 70 percent.

Giammattei’s administration has continued the trend of dismantling anti-corruption bulwarks, through prosecution of the judges, lawyers and activists involved in those efforts.

Accusations of corruption have also permeated the Guatemalan public prosecutor’s office in recent years. Both Attorney General Maria Consuelo Porras, who was controversially re-elected in May 2022, and Rafael Curruchiche, head of the Office of the Special Prosecutor Against Impunity, have been sanctioned by the United States for corruption and anti-democratic actions.

Critics say Guatemala is currently undergoing its greatest challenge since the country’s return to democracy in 1985, after decades of military rule. Back then, those democratic reforms paved the way for the 1996 peace accords that brought an end to the country’s 36-year-long internal conflict.

But for those who lived through those tumultuous times, Guatemala’s current democratic crisis is a painful setback.

“I struggled for the peace process so that there would be peace in Guatemala,” said Claudia Samayoa, a founder of the Human Rights Defenders Protection Unit in Guatemala (UDEFEGUA). Her organisation grew out of the peace accords and sought to implement its terms in the post-conflict period.

But Samoyoa explained that UDEFEGUA has likewise come under attack, with its leadership facing accusations of influence peddling in relation to Zamora’s case. The organisation has denied those allegations, dismissing them as a smear campaign against its human rights work.

“We have regressed in the exercise of the most basic right of defence,” Samayoa said. “These cases are backwards.”

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA

‘News Deserts’ Are Rampant in Latin America

A photo of journalists dedicated to covering the agendas of nearby communities, like these ones in a town in Colombia, is uncommon in poor areas of Latin American countries, where millions of people have no access to information of local interest. CREDIT: Chasquis Foundation

- Without the means to receive information about what is happening around them, millions of Latin Americans who live in poor remote rural or impoverished urban areas inhabit veritable news deserts, according to an increasing number of studies conducted by journalistic organizations in the region.

There are, for example, 29 million people in Brazil, 10 million in Colombia, seven million in Venezuela and up to three-quarters of the Argentine territory without access to journalism due to the absence of media outlets, or because the few existing local outlets are dedicated to entertainment, rather than news.

“When we talk about information deserts, we are also talking about what a robust media ecosystem implies: that there are not only enough media outlets, but also pluralism,” said Jonathan Bock, director of the Colombian Foundation for Press Freedom (FLIP).

This plurality must encompass “the topics that are covered, diversity of formats, media that address different audiences. A healthy ecosystem,” Bock added in a conversation with IPS from the Colombian capital.

A Jun. 7 forum organized by the Venezuelan branch of the Press and Society Institute (IPYS) displayed atlases and maps on news deserts in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela, based on research by organizations of journalists and academics from those countries.

Even without extrapolating from the results of these assessments, it is possible to estimate that news deserts affect a good part of the region, judging by the structural deficiencies of the population, and by conflictive situations in the media and journalism in nations such as those of Central America and the Andes.

“The social and geographical marginalization found in parts of our countries means that important segments of the population are in these news deserts. For example, indigenous populations lacking media outlets in their languages,” Andrés Cañizález, founder and director of the Venezuelan observatory Medianálisis, told IPS.

Journalistic organizations from Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela show maps or atlases that indicate, using colors, the most and least deserted areas in terms of access to news in their respective countries. CREDIT: IPS

Atlases and statistics

A study by the Argentine Journalism Forum (FOPEA), coordinated by Irene Benito, took a census of 560 areas in that country and considered 47.9 percent of them news deserts, 25.2 percent in “semi-desert” conditions, 17.1 percent as “semi-forests”, and 9.8 percent as “forests”, or areas with an abundance of media outlets and news.

“As in other Latin American nations, in many areas there are media outlets and journalists, but there is no quality coverage. They deal with other things, not the interests of their communities, while the propaganda apparatus of the powers-that-be is in overly robust health,” Benito said in the IPYS forum.

In Brazil, the most recent News Atlas, released in March, recorded the existence of 13,734 media outlets in that country of 208 million inhabitants, but not a single one in 312 of its 5,568 municipalities. These 312 municipalities are home to 29.3 million people with no access to local news.

Although hundreds of online media outlets emerge every year “and now more municipalities have at least one or two media outlets, many are not independent or are biased, because they depend on the city government or religious movements,” said Cristina Zahar, from the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (ARAJI).

In a third of Colombia, where 10 of the country’s 50 million inhabitants live – many areas far from the big cities – there are no mass media, and in another third, home to 16 million people, the existing media outlets are dedicated to entertainment, according to FLIP’s Cartography of Information.

In Venezuela, seven million people live in municipalities where there are no media outlets, and that figure rises to 15 million – in a country of 28 million people – if municipalities with only one or two media outlets, considered “semi-deserts”, are included, according to IPYS.

Unlike other countries, “the situation has worsened, with the massive closure of radio stations ordered by the government – at least 81 in 2022 alone, and 285 since 2003 – with radio being the medium that has the greatest penetration in remote areas,” Daniela Alvarado, head of freedom of information at IPYS, told IPS.

Remote rural areas far from the main cities and often in border regions are among the most affected by deficient infrastructure and lack of media outlets that enable local residents access to general information about their local environment and possibilities of participation in decisions that concern them. CREDIT: ECLAC

Exclusion, once again

In the case of Colombia, one cause for the breadth of news deserts is violence, “war, one of whose strategic aims is to pressure or close down news, journalism that can reveal, report, warn and monitor what happens in areas of conflict,” said Bock.

In 45 years of armed conflict in Colombia, 165 journalists were murdered, “strategic killings, because they reported on things, and became symbols,” Bock stressed.

“But it also has to do with a different kind of exclusion, of weak economies and little interest on the part of politics and government institutions in promoting independent and plural journalism, seen in some contexts as the enemy, and with society getting used to it and not demanding” independent reporting, the Colombian analyst said.

Another thing that has happened in countries in the region is that “traditional media, and many new digital outlets, emerged and are concentrated where there was already an audience and sources of advertising, which is combined with pre-existing inequalities to create an abyss between big cities and small towns and the countryside,” said Cañizález.

In news deserts, infrastructure failures abound and there are absences or deficiencies in internet services, with providers that do not access these territories, aggravating the situation of local inhabitants who often only have simple mobile phones and cannot obtain news and information through digital or social networks.

However, news deserts are not exclusive to rural, remote or border areas; in cities themselves there is a dearth of local media outlets, or the outlets have their own agendas on issues in poor urban communities, which are also impacted by the crises that face journalism in general.

This is the case of Venezuela, which “is caught up in a complex and continuous economic, political and social crisis that has led to the deterioration of its media ecosystem,” Alvarado said, adding that it also faces “a communicational hegemony (on the part of the State) that is manifested in censorship and self-censorship.”

Newspapers and television stations were driven to shut down, by government decision or suffocated due to lack of paper and advertising, or their sale paved the way for their closure; or, as in the case of many radio stations, closure is a constant looming threat. Online media suffer from internet cuts and harassment of their journalists.

Even in urban areas, such as this one in Caracas, the adverse climate of news deserts has an impact, for example with the closure of print media outlets caused by political decisions or economic crises, which forces traditional kiosks to subsist by replacing newspapers, which are no longer available, with candy and snacks. CREDIT: Public domain

What can be done?

“The challenge seems immeasurable, but we are not sitting quietly by, we must not give up on what is our right as a community public service,” said Benito.

The State “should promote, at least in the area of its competence, which is radio, television and internet, inclusive policies throughout the nation’s territory, guaranteeing basic rights, including the right to communication and information for all citizens,” stated Cañizález.

Zahar said that “sustainability is the challenge,” due to the difficulties many new media outlets, local or not, face in supporting themselves, and the advantages of digital media “that have fewer barriers to entry, can experiment with formats and financing mechanisms, and make quick changes.”

Bock said “we must think about the financing of journalism where there are fragile economies, see it as a public service but an independent one, to address the training of people practicing journalism in those places.”

Together with the support of the government and the international community, “models could be developed in which the big media sponsor local media in very small places or where there is clearly a news desert,” Cañizález said.

“But that’s still not even discussed in a number of our countries,” he said. “It is an issue that concerns journalism but has not drawn public attention. The debate is still very much confined to reporters.”

No comments:

Post a Comment