By Andy Corbley

-Nov 24, 2023

(Image credit Sonia Díaz-Navarro et al. via Live Science)

Researchers don’t know why, but a late-Neolithic, early-Copper Age woman underwent two cranial surgeries throughout her adult life—newly found archaeological remains from Spain have revealed.

Imagine for a moment everything that a successful surgery requires: orderlies, razor-sharp implements, anesthetic, disinfectant, and anatomical knowledge of the affected are the bare necessities for a procedure, none of which are common finds among Stone Age habitations

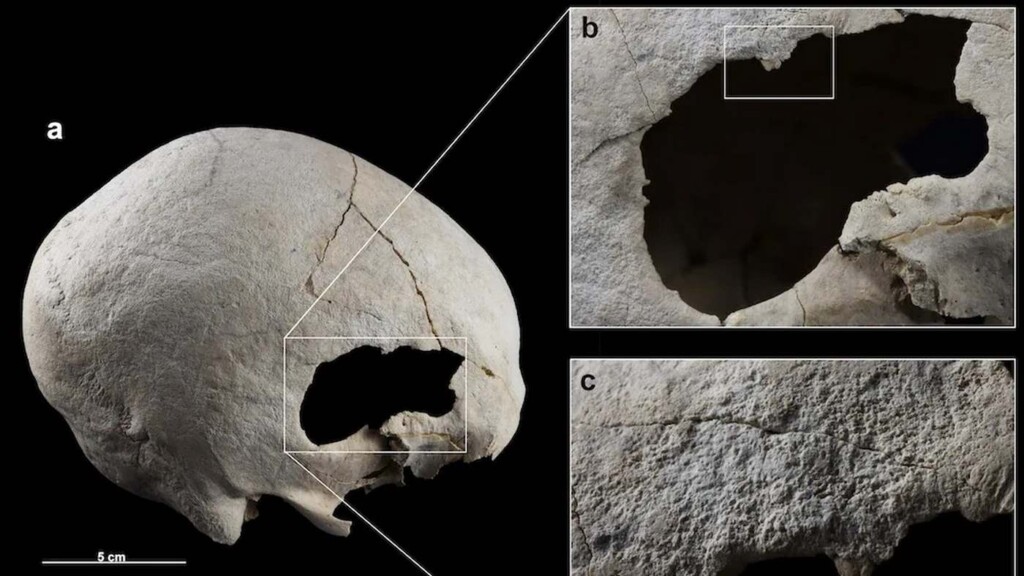

Yet in a burial site at Camino del Molino, located in Caravaca de la Cruz in Southeastern Spain, the skull of a 35 to 40-year-old woman was found with expertly made trepanations, or surgical entries into the cranium.

Trepanations mean the surgeon was trying to access the dura mater, the outermost layer of tissue surrounding the brain and spinal cord, and forensic analysis showed it was neither a wound of violence, nor some form of ritual cannibalism, because the areas around the trepanations were clean; without fractures, and the woman lived months after the second of the two procedures was finished.

It’s a stunning demonstration of medical knowledge and acumen for a people who had only just barely worked out the smithing of copper tools.

It also demonstrates the value that these primitive societies placed on the lives of loved ones, as this woman might already have been a grandmother and near the end of her life, yet was operated on twice in her twilight years, which would have included a substantial period of recovery during which she contributed no food or labor to the community while still consuming food collected by others.

The funerary site of Camino del Molino contains 1,348 individuals, and this woman who had lived a full life for a Neolithic/Copper Age human, lived months after the second of two surgeries in the same part of the brain was concluded. She eventually died during the period of the funerary pit’s second use phase which stretched from 2566 to 2239 BCE. The Copper Age woman’s skeleton as seen at the burial site. (Image credit: Sonia Díaz-Navarro et al. via Live Science)

The Copper Age woman’s skeleton as seen at the burial site. (Image credit: Sonia Díaz-Navarro et al. via Live Science)

“This is a cranial region rarely documented in prehistoric trepanations, as it contains the temporalis muscles and important blood vessels,” the authors write in their paper on the discovery in the International Journal of Paleopathology.

One of the authors spoke to Live Science about their discovery, describing the full extent of the procedure and what it must have required in a Paleolithic environment.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE: 24,000-Year-Old Cave Art Suddenly Found in Well-Known Paleolithic Cave Shelter in Spain

“This [trepanation] involves rubbing a rough-surfaced lithic [stone] instrument against the cranial vault, gradually eroding it along all its edges to create the hole,” said Sonia Díaz-Navarro, corresponding author on the paper from the Department of Prehistory, Archaeology, and Anthropology at the University of Valladolid.

“To perform this surgery, the affected individual likely had to be strongly immobilized by other members of the community or previously treated with a psychoactive substance that would alleviate pain or render them unconscious,” she said, adding that plants with natural antibacterial properties must have been used to prevent the obvious and serious risk of infection

Two overlapping holes were discovered between the woman’s temple and the top of her ear. The first was 2.1 inches wide by 1.2 inches long, and the second was smaller, at 1.3 by 0.47 inches, created into the already-healed bone tissue of the first trepanation.

ANOTHER CASE OF PREHISTORIC SURGERY: Evidence of Amputation in Prehistoric Times Shows Patient Surviving for a Decade–Proves Medical Expertise Existed

The authors determined that it must have been this rubbing or scraping technique that was used, rather than drilling, as it was safer and presented a lower risk of bleeding out. Despite the obvious difficulty in the act, the authors note that the whole literature of ancient or prehistoric surgery has demonstrated little detectable error in the use of the bladed stones.

While holes in her head were not the result of a wound inflicted by another human or animal, the authors can’t rule out the possibility that the surgery was performed as the result of a wound or injury, as other skeletons in the Camino de Molino bear signs of trauma.

Researchers don’t know why, but a late-Neolithic, early-Copper Age woman underwent two cranial surgeries throughout her adult life—newly found archaeological remains from Spain have revealed.

Imagine for a moment everything that a successful surgery requires: orderlies, razor-sharp implements, anesthetic, disinfectant, and anatomical knowledge of the affected are the bare necessities for a procedure, none of which are common finds among Stone Age habitations

Yet in a burial site at Camino del Molino, located in Caravaca de la Cruz in Southeastern Spain, the skull of a 35 to 40-year-old woman was found with expertly made trepanations, or surgical entries into the cranium.

Trepanations mean the surgeon was trying to access the dura mater, the outermost layer of tissue surrounding the brain and spinal cord, and forensic analysis showed it was neither a wound of violence, nor some form of ritual cannibalism, because the areas around the trepanations were clean; without fractures, and the woman lived months after the second of the two procedures was finished.

It’s a stunning demonstration of medical knowledge and acumen for a people who had only just barely worked out the smithing of copper tools.

It also demonstrates the value that these primitive societies placed on the lives of loved ones, as this woman might already have been a grandmother and near the end of her life, yet was operated on twice in her twilight years, which would have included a substantial period of recovery during which she contributed no food or labor to the community while still consuming food collected by others.

The funerary site of Camino del Molino contains 1,348 individuals, and this woman who had lived a full life for a Neolithic/Copper Age human, lived months after the second of two surgeries in the same part of the brain was concluded. She eventually died during the period of the funerary pit’s second use phase which stretched from 2566 to 2239 BCE.

The Copper Age woman’s skeleton as seen at the burial site. (Image credit: Sonia Díaz-Navarro et al. via Live Science)

The Copper Age woman’s skeleton as seen at the burial site. (Image credit: Sonia Díaz-Navarro et al. via Live Science)“This is a cranial region rarely documented in prehistoric trepanations, as it contains the temporalis muscles and important blood vessels,” the authors write in their paper on the discovery in the International Journal of Paleopathology.

One of the authors spoke to Live Science about their discovery, describing the full extent of the procedure and what it must have required in a Paleolithic environment.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE: 24,000-Year-Old Cave Art Suddenly Found in Well-Known Paleolithic Cave Shelter in Spain

“This [trepanation] involves rubbing a rough-surfaced lithic [stone] instrument against the cranial vault, gradually eroding it along all its edges to create the hole,” said Sonia Díaz-Navarro, corresponding author on the paper from the Department of Prehistory, Archaeology, and Anthropology at the University of Valladolid.

“To perform this surgery, the affected individual likely had to be strongly immobilized by other members of the community or previously treated with a psychoactive substance that would alleviate pain or render them unconscious,” she said, adding that plants with natural antibacterial properties must have been used to prevent the obvious and serious risk of infection

Two overlapping holes were discovered between the woman’s temple and the top of her ear. The first was 2.1 inches wide by 1.2 inches long, and the second was smaller, at 1.3 by 0.47 inches, created into the already-healed bone tissue of the first trepanation.

ANOTHER CASE OF PREHISTORIC SURGERY: Evidence of Amputation in Prehistoric Times Shows Patient Surviving for a Decade–Proves Medical Expertise Existed

The authors determined that it must have been this rubbing or scraping technique that was used, rather than drilling, as it was safer and presented a lower risk of bleeding out. Despite the obvious difficulty in the act, the authors note that the whole literature of ancient or prehistoric surgery has demonstrated little detectable error in the use of the bladed stones.

While holes in her head were not the result of a wound inflicted by another human or animal, the authors can’t rule out the possibility that the surgery was performed as the result of a wound or injury, as other skeletons in the Camino de Molino bear signs of trauma.

No comments:

Post a Comment