Moira Ritter

Wed, January 17, 2024

Archaeologists exploring the area near a hilltop castle in Switzerland found pieces of burned-down walls and charred framing — and discovered the ruins of a medieval cellar.

Within the cellar, experts found evidence of a weaving center and an array of metal objects indicating the existence of a forge. As they looked closer, the team spotted something else: a nearly fully preserved iron gauntlet.

The piece of armor is an exceptional discovery dating back about 700 years to the 14th century, according to a Jan. 16 news release from the Canton of Zürich.

Archaeologists have previously discovered similar artifacts, but most are from no later than the 15th century, officials said. Although five other gauntlets from earlier have been found, none are in near as good condition as the newly discovered armor.

The right hand four-fold finger glove is made of iron plates placed on top of one another, similar to scales, and connected with rivets, experts said. The pieces of the glove were then attached to the textile or leather inside with more rivets.

The armor offered its wearer a great range of movement and flexibility, likely so they could hold a sword while wearing the glove, Lorena Burkhardt, a project manager on the archaeology team, said in a Jan. 16 Facebook video shared by officials.

Inside the cellar, archaeologists also unearthed a trove of ancient metal objects, including a mold, hammer and tweezers, according to Burkhardt. The cellar was likely used as a weaving center where metal objects were forged.

Fragments of the corresponding left hand gauntlet were also discovered, archaeologists said.

Experts found the cellar near Kyburg Castle, which is about 15 miles northeast of Zürich.

The first mention of Kyburg Castle was in 1079, and its name means refuge castle, according to its website. Since 1865, the castle has functioned as a museum.

Tom Metcalfe

Tue, January 16, 2024

The remains of rare silver coins that were part of religious worship in an ancient Greek settlement.

Archaeologists in Greece have unearthed part of one of the largest hydraulic projects from the ancient world: an aqueduct that the Roman emperor Hadrian built to supply water to the city of Corinth.

The remnants of the aqueduct were discovered in October during excavations at the archaeological site of Tenea, an ancient Greek town a few miles south of Corinth, according to a translated statement from the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Hadrian, who ruled the Roman Empire from A.D. 117 to 138, ordered the aqueduct built to carry water for more than 50 miles (80 kilometers), from Lake Stymphalia in the hills to the west of the city.

Aqueducts were already known in Greece, and Hadrian also had one built to supply water to Athens. But his aqueduct to Corinth is mentioned as a monumental work by ancient writers.

The rediscovered section is just over 100 feet (30 meters) long and runs from north to south alongside a river. It consists of a channel covered by a semicircular roof, both made of stone and mortar.

Related: Vast subterranean aqueduct in Naples once 'served elite Roman villas'

The exterior walls are more than 10 feet (3.2 m) high, and the interior space where the water flowed is about 2 feet (60 centimeters) wide and 4 feet (1.2 m) high.

Rare coins

A team excavating near the aqueduct also found tombs from the Greek

Image 3 of 3

Structures were also built at the site in the Roman period after the first century BC, Including furnaces and a press for olive oil.

Corinth was one of the great cities of ancient Greece. It is about 40 miles (70 km) west of Athens, on the far side of the great isthmus that connects the Peloponnese Peninsula to the rest of Greece.

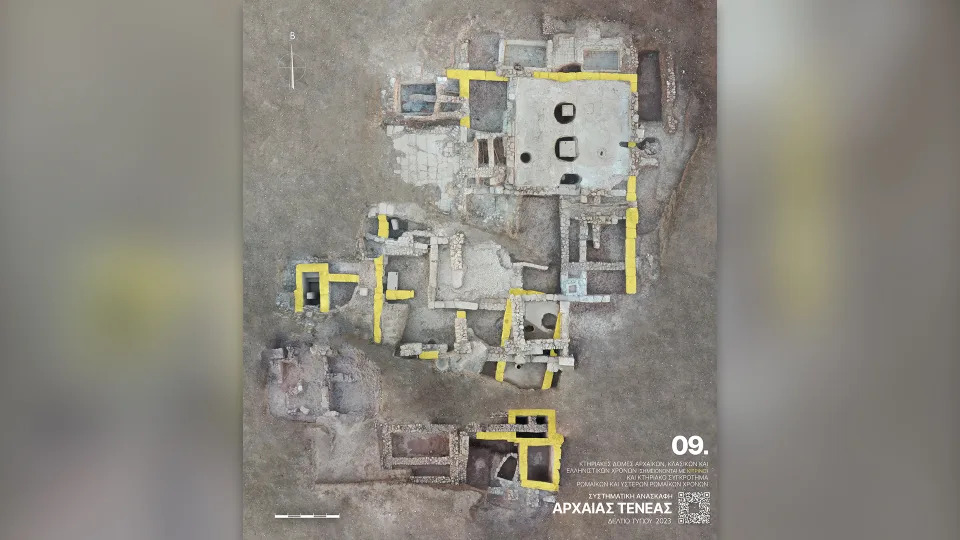

The archaeologists also announced the discovery of a building complex in Tenea dating to the late Archaic period (roughly the eighth to fifth centuries B.C.) until the Hellenistic period (roughly the second and first centuries B.C.) that included places of worship for Greek heroes or gods.

Image 1 of 3

The archaeologists found pieces of pottery from the Archaic and Hellenic period of the site's occupation, roughly between the 8th century and the first century B.C.

Image 2 of 3

The also found ornately decorated

Image 3 of 3

Pottery objects were also found in the tombs from the Archaic period, including small flasks and parts of metal compasses for drawing circles (shown in the upper center).

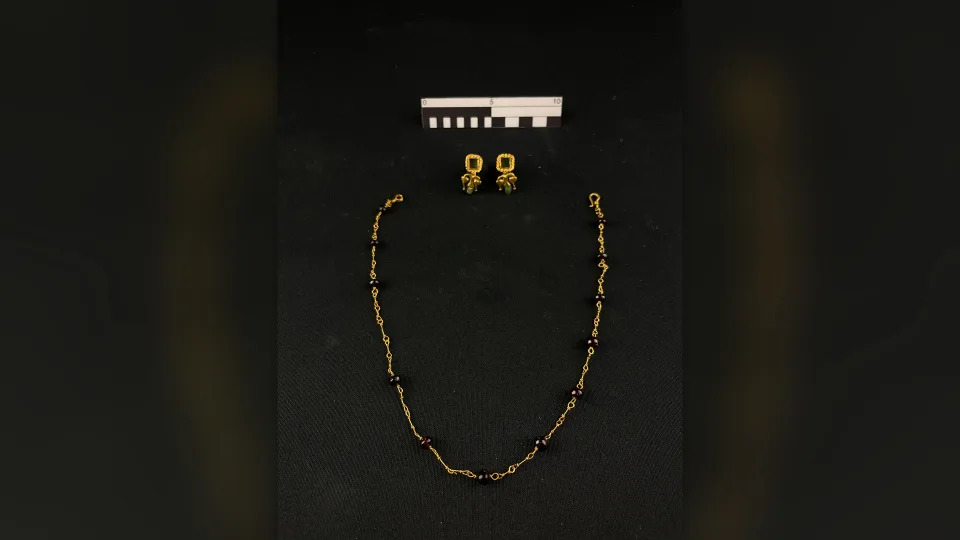

They also found 29 rare silver coins alongside a portable clay altar, as well as a miniature vase and a figurine of a horse and rider. The coins date to the late sixth century B.C. and include some of the rarest ancient Greek coins ever found, including three silver staters minted at Olympia during different ancient Olympic Games, which was then a religious festival celebrated every four years.

The coins were linked to the religious use of the site, evidence of which — including female and animal figurines — was found during excavations in 2022, according to the statement.

RELATED STORIES

—2,700-year-old temple with altar overflowing with jewel-studded offerings unearthed on Greek island

—2,800-year-old figurines unearthed at Greek temple may be offerings to Poseidon

—Hidden colors and intricate patterns discovered on the 2,500-year-old Parthenon Marbles from ancient Greece

The latest excavations have also uncovered structures built during the early period of Roman rule, after the first century B.C., including furnaces and an olive press, a Roman-era cemetery with elaborate stone tombs, and the remains of a prehistoric settlement thought to be from the Bronze Age, roughly 2600 to 2300 B.C. — long before the legendary fall of Troy, which is supposed to have happened around the 12th century B.C.

Artifacts from this earliest settlement included obsidian tools, animal figurines and large amounts of fine pottery. Much of the pottery was imported from the Greek areas of Aegina, Attica, Argolida and Corinth, showing the trading contacts the settlement had established with these areas, the statement said.

Ancient Roman necropolis holding more than 60 skeletons and luxury goods discovered in central Italy

Kristina Killgrove

Wed, January 17, 2024

Gold necklace in situ around a partially excavated skeleton.

A Roman-era necropolis that likely holds the remains of the upper crust has been discovered in central Italy, and it contains nearly 60 graves replete with gold jewelry and the remains of leather footwear, pottery and other precious goods.

The cemetery, found ahead of construction work for a solar energy project in the town of Tuscania, may have been associated with a hotel-like villa that served as a way station for important travelers, such as provincial officials.

"The jewels, but also the glass, pottery, the footwear, the numerous coins, give us an image of people who enjoyed a certain well-being and could afford some small luxuries," Emanuele Giannini of the archaeology firm Eos Arc and the lead archaeologist at the site, told Live Science in an email.

Excavation of the necropolis.

Most of the tombs were in the so-called "cappuccina" style — a common burial type in which the deceased were covered with stone or ceramic tiles arranged in an A-frame shape. However, the archaeologists also found simple graves with no such covering, as well as skeletons contained in large ceramic vessels and evidence of some cremations.

Related: Elite Roman man buried with sword may have been 'restrained' in death

Burial of two people.

Dated to the height of the Roman Empire, to between the second and fourth centuries A.D., the necropolis was likely associated with a way station called a "mansio." There, dignitaries and other officials could stop for rest and refreshments while on government business. Giannini said that historical sources mention a mansio called Tabellaria along the via Aurelia, an ancient road which ran roughly from Pisa to Rome; the location of this mansio is just 1,640 feet (500 meters) from the cemetery, suggesting a connection.

Image 1 of 2

Tomb containing a person and a ceramic pot.

Image 2 of 2

Cappuccina style tomb.

So far, archaeologists have made only basic assessments of the newfound skeletons in terms of sex and age-at-death, and they suggest that the people lived in an urban context. "Discovering who they were is part of my research," Giannini said.

Image 1 of 2

Gold earrings after conservation.

Image 2 of 2

Gold necklace and earrings after conservation.

He and his team plan to undertake genetic studies to learn more about the 67 people who were buried in the necropolis, including trying to figure out whether the tombs that contained more than one person held the remains of family members.

RELATED STORIES

—Roman-era tomb scattered with magical 'dead nails' and sealed off to shield the living from the 'restless dead'

—'Completely unique' Roman mausoleum discovered in rubble of London building site

—Dozens of decapitated skeletons uncovered at ancient Roman site in England

In addition, the artifacts found in the excavation are being studied and restored, Giannini said, and when that is complete, they will be exhibited in a local museum. "We have already done a lot, but much still remains to be done," he said.

Using the latest technology, Giannini and his team hope to extend their research by reconstructing the lives of the ancient population of the area in as detailed a manner as possible. The project is "ambitious but realistic," according to Giannini, but key to better understanding how people lived during the time of the Roman Empire.

No comments:

Post a Comment