Manufacturing Jobs: Unions Made Them Good, Not the Factories

Detroit Industry Murals, Diego Rivera, Detroit Institute of Art. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

The effort to bring back manufacturing jobs has been a major theme in the 2024 election. Both parties say they consider this a high priority for the next administration. However, there is a notable difference in that the Biden-Harris administration has actively supported an increase in unionization, while the Republicans have indicated at best neutrality if not outright hostility towards unions.

This distinction is important in the context of manufacturing jobs. Many people seem to assume that manufacturing jobs are automatically good jobs, paying more than non-manufacturing jobs.

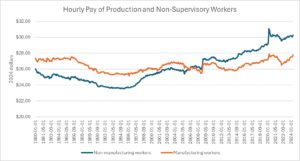

While that was true four decades ago, before the massive job loss of manufacturing jobs due to trade, it is not clear this is still the case. The figure below shows the average hourly pay, in 2024 dollars for production and non-supervisory workers in manufacturing and elsewhere in the private sector.[1]

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and author’s calculations.

As can be seen, workers in manufacturing had a substantial edge in pay at the start of this period, earning a premium of more than 5.0 over their counterparts in other industries. However, this flips in 2006, and since then pay for non-manufacturing workers has outpaced pay for workers in manufacturing. In the most recent data, non-manufacturing workers get almost 9.0 percent more in hourly pay than workers in manufacturing.

To be clear, this is not a comprehensive comparison of relative pay. A full comparison would have to incorporate benefits and also adjust for differences in the workforce, such as education and location. An analysis done by Larry Mishel at the Economic Policy Institute in 2018 found that there was still a substantial premium for manufacturing workers over the years 2010-2016 when controlling for these factors. A more recent analysis from the Federal Reserve Board found that this premium had disappeared altogether, even when controlling for these factors.

While further research may produce different results, there is little doubt that the manufacturing premium has been sharply reduced, if not eliminated altogether, over the last four decades. The main reason for the decline in the premium is not a secret, there has been a huge drop in the percentage of manufacturing workers who are unionized.

In 1980, 32.3 percent of manufacturing workers were union members. This compares to a unionization rate of 15.0 percent for the rest of the private sectors. By comparison, in 2023 just 7.9 percent of manufacturing workers were union members, only slightly higher than the 5.9 percent rate for the private sector as a whole.

The implication of the loss of the wage premium coupled with the decline in unionization rates is that there is little reason to believe that an increase in the number of manufacturing jobs will mean more good jobs, unless they are also unionized. It is not the factories that make these jobs good jobs, it is the unions.

Notes.

[1] The category of production and non-supervisory workers includes roughly 80 percent of the workforce. It excludes managers and highly paid professionals, so changes in pay at the top end will not have much impact on these data.

This first appeared on Dean Baker’s Beat the Press blog.

No comments:

Post a Comment