The United States is witnessing a boom in manufacturing investment, stimulated by massive government subsidies, but the skilled workforce necessary to support it is severely lacking.

Blog Post by Benn Steil and Elisabeth Harding

September 27, 2024

COUNCIL ON FORIEGN RELATIONS (CFR)

In order to make supply chains more resilient, boost domestic manufacturing, and compete with China in “strategic” industries, the Biden administration has—across the Inflation Reduction Act, Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and CHIPS and Science Act—pledged over $2.1 trillion in investment incentives.

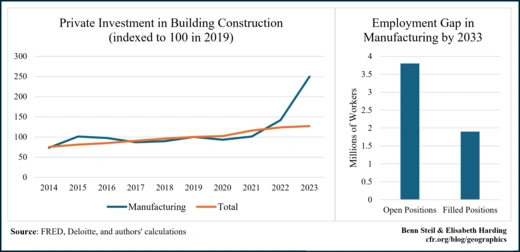

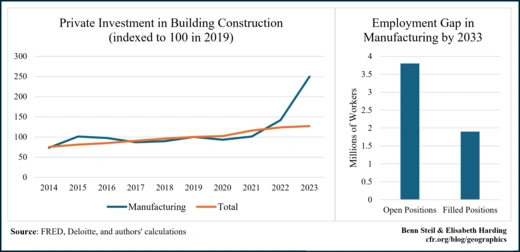

As a result, private investment in construction of manufacturing buildings, as shown in the left-hand figure above, has almost tripled since 2019—rising significantly more rapidly than investment in building construction overall. As shown in the right-hand figure, however, the United States lacks the human capital to sustain a manufacturing boom. By 2033, 3.8 million new positions will open, yet only half of these are likely to be filled.

Nearly 75 percent of this employment gap will owe to retirements. A quarter of U.S. manufacturing workers are over the age of 54, and those between 55 and 64 leave the industry at a higher rate than do those in other industries. Though the CHIPS Act gives preference to companies that provide workforce training and education investments, and the administration has promised to create jobs requiring only apprenticeships, a huge mass of new skilled entrants in areas such as engineering and computer science will still be required to replace the coming wave of retirees. Already, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) has had to delay production in its chip manufacturing plant in Arizona owing to a shortage of specialized workers. Going forward, reducing such shortages will require far wider policy initiatives, such as expanding scholarships for technical-college training and raising visa numbers for skilled foreign workers.

In order to make supply chains more resilient, boost domestic manufacturing, and compete with China in “strategic” industries, the Biden administration has—across the Inflation Reduction Act, Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and CHIPS and Science Act—pledged over $2.1 trillion in investment incentives.

As a result, private investment in construction of manufacturing buildings, as shown in the left-hand figure above, has almost tripled since 2019—rising significantly more rapidly than investment in building construction overall. As shown in the right-hand figure, however, the United States lacks the human capital to sustain a manufacturing boom. By 2033, 3.8 million new positions will open, yet only half of these are likely to be filled.

Nearly 75 percent of this employment gap will owe to retirements. A quarter of U.S. manufacturing workers are over the age of 54, and those between 55 and 64 leave the industry at a higher rate than do those in other industries. Though the CHIPS Act gives preference to companies that provide workforce training and education investments, and the administration has promised to create jobs requiring only apprenticeships, a huge mass of new skilled entrants in areas such as engineering and computer science will still be required to replace the coming wave of retirees. Already, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) has had to delay production in its chip manufacturing plant in Arizona owing to a shortage of specialized workers. Going forward, reducing such shortages will require far wider policy initiatives, such as expanding scholarships for technical-college training and raising visa numbers for skilled foreign workers.

No comments:

Post a Comment