(RNS) — As more institutions adopt policies against caste discrimination, disagreements about caste's prevalence among those in the Hindu diaspora are stronger than ever.

Supporters and opponents of a proposed ordinance to add caste to Seattle’s anti-discrimination laws attempt to out-voice each other during a rally at Seattle City Hall, Feb. 21, 2023, in Seattle. (AP Photo/John Froschauer)

Richa Karmarkar

December 10, 2024

(RNS) — Nearly a decade ago, a newly migrated Karthikeyan Shanmugam, an IT engineer from Tamil Nadu, in southern India, was puzzled, to say the least, at the caste conversations among the Hindus he met in the Bay Area.

As they discussed the California Department of Education’s 2016 battle with Hindu advocacy organizations over mentions of India’s hierarchy of hereditary social classes in the state’s social studies textbooks, Shanmugam realized, he said in a recent interview, that some of his fellow Hindus were unconvinced that the caste system needed to be addressed at all.

Shanmugam is among those American Hindus who believe that the Indian diaspora has grown to the point that caste needs to be addressed out of its context in India. “Caste is something very apparent as part of the Indian perspective,” Shanmugam told RNS. “It has to be taught, and it has to be taught properly, the right way. If you try to hide caste, then there is no solution to it.”

Disagreements about whether caste originated from the Hindu religion or South Asian history more generally came to a fever pitch in California last year, when a landmark bill designating caste as an official category of discrimination was vetoed by Gov. Gavin Newsom after intense lobbying.

More than a dozen universities, colleges and companies have adopted caste as a protected category in their discrimination policies, opposed by similar groups that argued the inclusion would only mischaracterize all in the micro-minority for following discriminatory practices that had long been disavowed in their homeland.

Thenmozhi Soundararajan, front center, leads demonstrators marching in favor of SB 403 near the California Capitol building in Sacramento, Sept. 11, 2023. (Photo courtesy of Equality Labs)

As these institutions implement anti-caste policies, Hindu Americans feel it imperative to discuss the unintended consequences, and hidden complexities, of “the caste problem.”

RELATED: Rutgers task force report urges university to add caste discrimination ban

The problem, said Shanmugam, is that those Hindus living in the United States who don’t see caste often miss it because they haven’t suffered caste discrimination, likely because they themselves are higher on the “caste ladder.” These upper-caste Hindus, or Brahmins, he said, make up the majority of Hindus who initially had the access and money to build a life in the U.S.

“They have to understand what social justice is, and how they benefit from their caste privilege,” said Shanmugam. “They first have to acknowledge it.”

Shanmugam, who is not a Brahmin, knew from his own experience that caste divisions persist in the U.S. He has known co-workers to try to “sniff out” his caste with pointed religious questions, and seen blatant shaming of meat eaters in his social circles, as it could indicate a lower caste.

So why, asked Shanmugam, did it feel as if many Hindu Americans were denying this reality?

In part to raise awareness about caste frictions, Shamugan co-founded the Ambedkar King Study Circle, a support group for other recent immigrants who followed the teachings of caste abolitionist Bhimrao Ambedkar, who is said to have influenced the thinking of Martin Luther King Jr., whose son Martin Luther King III once called them “brother revolutionaries.”

People demonstrate against Senate Bill 403 during a rally near the California state Capitol in Sacramento, Sept. 9, 2023. (Photo courtesy of Sangeetha Shankar/HAF)

But some Hindus maintain that even talking about the caste system outside its native contexts not only unnecessarily extends its power but paints Hinduism as essentially discriminatory. The argument against California’s caste discrimination bill and other institutional caste policies from these advocates held that they were being pushed by campus or corporate DEI officials.

Last week, a new report from the Network Contagion Research Institute, a nonprofit center at Rutgers University that studies misinformation and hate ideology, found that caste education can actually increase bias, saying, “anti-oppressive pedagogy increases hostility, distrust, and punitive attitudes — escalating tensions instead of fostering inclusion.”

In other words, those exposed to a DEI curriculum about caste equity written by Equality Labs, a Dalit, or lower-caste civil rights group, were more likely to perceive Brahmins as an inherently oppressive group, or perceive discrimination when there isn’t any evidence of it, said Indu Viswanathan, a researcher who helped produce the report.

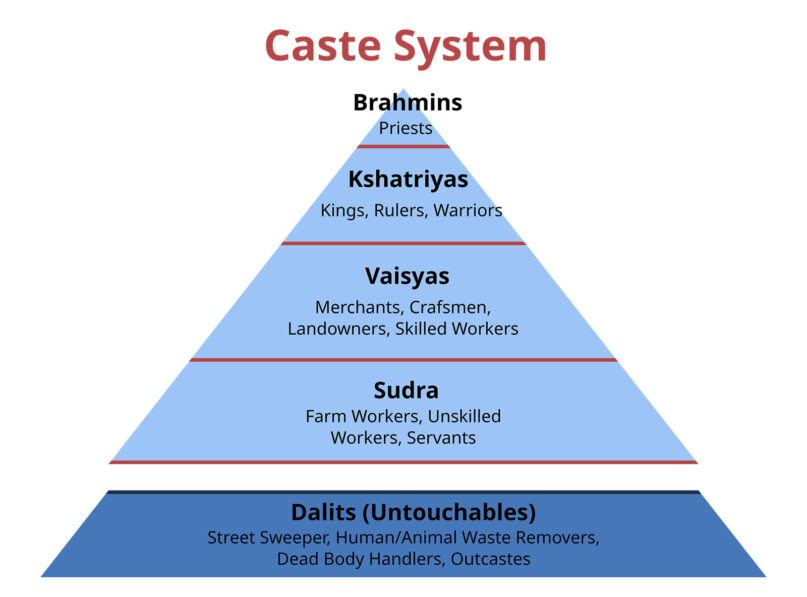

Many Americans’ introduction to the caste system, she said, begins as early as middle school, when they find plastered in their social studies textbook a four-section pyramid, with Brahmins at the top and Shudras, or untouchables, at the bottom. The chart has become infamous among Indian American students, who are often faced with uncomfortable questions as a result.

The Caste System pyramid, as seen in many textbooks. (Image courtesy Wikimedia/Creative Commons)

“Categorical discrimination exists in every society,” said Viswanathan, “but when it’s represented as the bulk of what you need to know about a group of people, that’s when things begin to get skewed, and your concepts of that group of people and the purpose of their tradition start to become skewed.”

The versions of caste that come from the Hindu Scriptures, said Viswanathan, can’t be explained in a single diagram, nor can Western frameworks of the “food chain” articulate the nuances of caste, including the checks historically placed on those of a higher status, the role of regional and linguistic communities in caste designations, and the years of reparations put forth for those born in so-called backward castes.

DEI circles in schools and offices, then, she said, leave little room for progressive-minded individuals like herself to push back against the dominant narrative, which she sees as turning increasingly “anti-Brahmin.”

“We are a community like no other,” she said. “We’re a small group in the United States, but we maintain the incredible, sort of unimaginable diversity of India, even amongst the diaspora. But the story that is being peddled is that whatever is happening in India is also happening here.”

Pushpita Prasad, of the advocacy organization Coalition of Hindus of North America, said the fight against institutional caste policies has been pulled off-track by a “feel-good ignorance” that exists among well-meaning, but uninformed, lawmakers. She said that though she has lived in the U.S. for 25 years, she never heard caste being discussed until Equality Labs released its first survey in 2016 — which has since been criticized by other researchers for its methodology.

“It’s interesting that DEI, a concept that should have been about teaching pluralism, has become fundamentally so linear that it divides the world into black and white, good and evil, and it can’t see beyond that,” said Prasad.

Raju Rajagopal. (Courtesy photo)

But Raju Rajagopal, a self-described “caste-privileged” Hindu who sits on the board of Hindus for Human Rights, a social justice advocacy group, said those who say they see no evidence of caste discrimination are “missing the point.”

“You may think that you’re being falsely accused, but until you’re able to put yourself in the shoes of the discriminated, at least show some understanding of why they feel this perception. Unless you can give some safe space for Dalits to openly talk about what they’ve gone through, you’re not going to have the data to say that.”

In Rajagopal’s eyes, mentions of caste will only increase as more Indians immigrate to this country. The difficult conversations that will result are unavoidable and require the participation of all Hindus, regardless of their views on its origins. It is thus the responsibility of Hindus, he says, to “educate the mainstream American community, not to distance ourselves from something that our ancestors have contributed heavily to, similar to racism.”

Talking about caste gives teachers and parents the chance to highlight how Indians have tried to mitigate its effects, Rajugopal said, such as India’s affirmative action effort known as the reservation system. “There’s plenty that we can highlight to the children to say, ‘This is a problem, but look at all the things that we have done now.’ We have to do our bit in America.”

No comments:

Post a Comment