Francis’s project for the Earth—a recovery of fellow feeling, with a special attention to the poor—is the only thing that can save us over time.

Pope Francis greets Swedish teenage environmental activist Greta Thunberg, right, during his weekly general audience in St. Peter's Square, at the Vatican, on Wednesday, April 17, 2019.

(Photo: Massimo Valicchia/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Apr 21, 2025

Just in case I thought one couldn’t feel more forlorn right now, the word came this morning of the death of Pope Francis. It hit me hard—not because I’m a Catholic (I’m a Methodist) but because I had always felt buoyed by his remarkable spirit. If he could bring new hope and energy to an institution as hidebound as the Vatican, there was reason for all of us to go on working on our own hidebound institutions—and if he could stand so completely in solidarity with the world’s poor and vulnerable, then it gave the rest of us something to aim for.

I thought this from the start, when he became the first pope to choose the name of Francis—that countercultural blaze of possibility in a dark time—and when he showed his mastery of the art of gesture, washing the feet of women, of prisoners, of Muslim refugees. (Only Greta Thunberg, with her school strike, has so mastered the power of gesture in modern politics).

But he brought that moral resolve to the question of climate change, making it the subject of his 2015 encyclical “Laudato Si,” the most important document of his papacy and arguably the most important piece of writing so far this millennium. I spent several weeks living with that book-length epistle in order to write about it for The New York Review of Books, and though I briefly met the man himself in Rome, it is that encounter with his mind that really lives with me. “Laudato Si” is a truly remarkable document—yes, it exists as a response to the climate crisis (and it was absolutely crucial in the lead-up to the Paris climate talks, consolidating elite opinion behind the idea that some kind of deal was required). But it uses the climate crisis to talk in broad and powerful terms about modernity.

The ecological problems we face are not, in their origin, technological, says Francis. Instead, “a certain way of understanding human life and activity has gone awry, to the serious detriment of the world around us.” He is no Luddite (“who can deny the beauty of an aircraft or a skyscraper?”) but he insists that we have succumbed to a “technocratic paradigm,” which leads us to believe that “every increase in power means ‘an increase of “progress” itself’… as if reality, goodness and truth automatically flow from technological and economic power as such.” This paradigm “exalts the concept of a subject who, using logical and rational procedures, progressively approaches and gains control over an external object.” Men and women, he writes, have from the start

intervened in nature, but for a long time this meant being in tune with and respecting the possibilities offered by the things themselves. It was a matter of receiving what nature itself allowed, as if from its own hand.

In our world, however, “human beings and material objects no longer extend a friendly hand to one another; the relationship has become confrontational.” With the great power that technology has afforded us, it’s become

easy to accept the idea of infinite or unlimited growth, which proves so attractive to economists, financiers, and experts in technology. It is based on the lie that there is an infinite supply of the Earth’s goods, and this leads to the planet being squeezed dry beyond every limit.

The deterioration of the environment, he says, is just one sign of this “reductionism which affects every aspect of human and social life.”

I think Francis’s project for the Earth—a recovery of fellow feeling, with a special attention to the poor—is the only thing that can save us over time. But it will take time—obviously for the moment we’ve chosen the opposite path, as exemplified by the fact that JD Vance, scourge of the refugee, darkened his last day on Earth.

In the meantime, Francis was very much a pragmatist, and one advised by excellent scientists and engineers. As a result, he had a clear technological preference: the rapid spread of solar power everywhere. He favored it because it was clean, and because it was liberating—the best short-term hope of bringing power to those without it, and leaving that power in their hands, not the hands of some oligarch somewhere.

As a result, he followed up “Laudato Si” with a letter last summer, “Fratello Sole,” which reminds everyone that the climate crisis is powered by fossil fuel, and which goes on to say

There is a need to make a transition to a sustainable development model that reduces greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere, setting the goal of climate neutrality. Mankind has the technological means to deal with this environmental transformation and its pernicious ethical, social, economic, and political consequences, and, among these, solar energy plays a key role.

As a result, he ordered the Vatican to begin construction of a field of solar panels on land it owned near Rome—an agrivoltaic project that would produce not just food but enough solar power to entirely power the city-state that is the Vatican. It is designed, in his words, to provide “the complete energy sustenance of Vatican City State.” That is to say, this will soon be the first nation powered entirely by the sun.

The level of emotion—of love—in this decision is notable. The pope named “Laudato Si” (“Praised be”) after the first two words of his namesake’s “Canticle to the Sun,” and “Fratello Sole” was even more closely tied—those are the words that the first Francis used to address Brother Sun. I reprint the opening of the Canticle here, in homage to both men, and to their sense of humble communion with the glorious world around us.

All praise be yours, my Lord, through all that you have made,

And first my lord Brother Sun,

Who brings the day; and light you give to us through him.

How beautiful is he, how radiant in all his splendor!

Of you, Most High, he bears the likeness.

The world is a poorer place this morning. But far richer for his having lived.

© 2022 Bill McKibben

Bill Mckibben is the Schumann Distinguished Scholar at Middlebury College and co-founder of 350.org and ThirdAct.org. His most recent book is "Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out?." He also authored "The End of Nature," "Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet," and "Deep Economy: The Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future."

Full Bio >

Scientific consensus, climate and Catholicism: A look back at Pope Francis’s environmental legacy

Pope Francis's legacy includes efforts to open the eyes of the world’s 1.3 billion Catholics to the dangers of climate change.

Pope Francis has died on Easter Monday, 21 April, aged 88, the Vatican has announced.

Elected in 2013 following the resignation of Pope Benedict XVI, he was the head of the Catholic Church for just over a decade.

He will be remembered in part for his efforts to open the eyes of the world’s 1.3 billion Catholics to the dangers of climate change.

Throughout his life, he was vocal about these risks, especially their impact on the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people.

"Pope Francis has been a towering figure of human dignity, and an unflinching global champion of climate action as a vital means to deliver it," UN climate chief Simon Stiell said on the passing of Pope Francis.

"Through his tireless advocacy, Pope Francis reminded us there can be no shared prosperity until we make peace with nature and protect the most vulnerable, as pollution and environmental destruction bring our planet close to ‘breaking point’."

Stiell added that Pope Francis "had a deep working knowledge of complex climate issues, and his leadership brought together those most powerful forces of faith and science to deliver unimpeachable truths, highlighting the costs of the climate crisis for billions of people".

"His Holiness’ passing will be felt profoundly by countless millions, but his message will live on: Humanity is community. And when any one community is abandoned – to poverty, starvation, climate disasters and injustice – all of humanity is deeply diminished, materially and morally, in equal measures."

‘The planet being squeezed dry’

During his leadership of the Catholic Church, Pope Francis frequently spoke about climate change.

Perhaps his most striking note on the subject was Laudato si’: On Care For Our Common Home, a 184-page landmark document published in 2015. In this pastoral letter, Pope Francis laments the state of environmental damage and global warming, criticising consumerism and taking aim at the “modern myth of unlimited material progress”.

“It is based on the lie that there is an infinite supply of the earth’s goods, and this leads to the planet being squeezed dry beyond every limit,” he wrote.

The text also lays out the scientific case for human-caused climate change, linking it to a moral perspective and warning of “serious consequences” if things don’t change. Pope Francis left no doubt that he backed the scientific consensus that global warming was down to greenhouse gases released by human activity.

This document also came just six months before COP21 - the UN climate change conference where the historic Paris Agreement was signed. Many believe it, and the Vatican’s involvement in negotiations, had a not insignificant impact on this outcome.

Delegations from Catholic countries made strong climate commitments during this COP. The Pope’s ability to speak to people across many divides paved the way for him to become even more deeply involved in future UN climate change conferences.

The Catholic Church and UN climate conferences

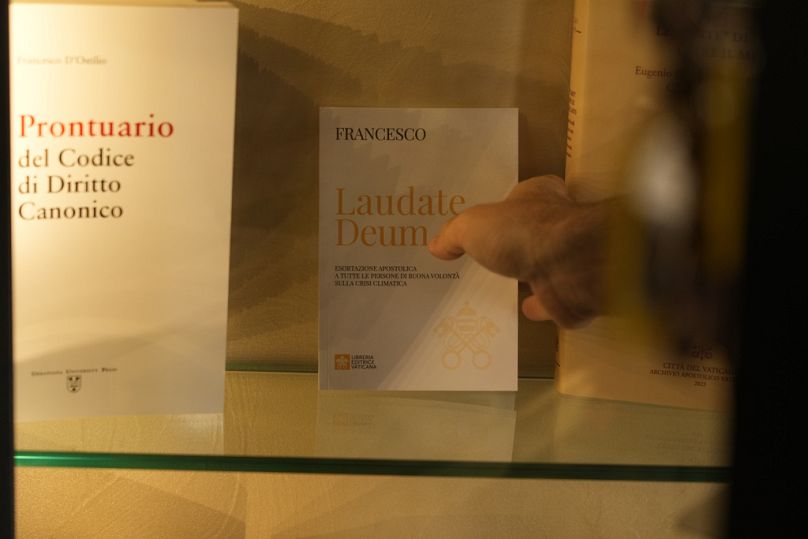

Ahead of COP28 in Dubai in 2023, Pope Francis revisited the topic with an updated treatise on climate change. Laudate Deum is an apostolic exhortation calling for urgent action on the crisis.

“With the passage of time,” he wrote, “I have realised that our responses have not been adequate, while the world in which we live is collapsing and may be nearing breaking point.”

This time, he specifically took aim at citizens of wealthy countries living an “irresponsible lifestyle.” In the US, for example, Pope Francis highlighted that emissions per person were two times higher than in China and seven times more than the average of the world’s poorest countries.

He also pinpointed the continued use of fossil fuels as the primary driver of climate change.

Pope Francis intended to go to COP28 himself, making history as the first Pope to address the climate change conference. Flu and lung inflammation, however, prevented him from travelling to Dubai, with his speech instead read by Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Parolin.

Again, drawing together moral obligations and scientific consensus, he criticised efforts to shift blame for the climate crisis to the rising population figures in poor countries. Instead, he singled out historic emitters “responsible for a deeply troubling ecological debt”.

Hitting on one of the main topics of COP28, he said it was only fair that these countries that have used excessive amounts of fossil fuels wipe out the debts of poorer nations. Who pays for the loss and damage done by climate change is an argument that still continues to this day.

Pope Francis was once again too unwell to travel to COP29 in Azerbaijan last year but sent a message to the UN climate conference. Vatican’s secretary of state, Cardinal Pietro Parolin, instead delivered his message to world leaders gathered in Baku.

He said that the "real challenge of our century” was indifference towards the climate crisis, emphasising that “indifference is an accomplice to injustice”.

The Pope appealed to countries which have contributed the most greenhouse gases to acknowledge their "ecological debt" to others.

He called for “a new international financial architecture” that was “based on the principles of equity, justice, and solidarity”.

The Catholic Church organises its own climate conference

Throughout his life and even up to the end, Pope Francis continued to highlight issues of inequality in the consequences of climate change.

In 2019, he backed calls for ecocide to be made the “fifth crime against peace” - an evil equivalent to genocide and ethnic cleansing - and declared it a sin. He has met with presidents, prime ministers, heads of state, CEOs, and boards of big companies over the years to talk about the issue.

And in May 2024, he organised the Catholic Church’s own three-day conference on climate resilience at the Vatican. Attendees included 16 mayors of international cities such as London Mayor Sadiq Khan and Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo, as well as governors from around the world.

Rather than solely focusing on mitigating climate change, it drew attention to the need for human adaptation. The Pope questioned political leaders on whether “we are working for a culture of life or for a culture of death.”

“The wealthier nations, around one billion people, produce more than half of the heat-trapping pollutants,” he told participants of the summit.

“On the contrary, the three billion poorer people contribute less than 10 per cent, yet they suffer 75 per cent of the resulting damage.”

This summit once again saw Pope Francis reiterate his belief that the destruction of the environment is an “offence against God” and a “structural sin” that endangers all people.

It is statements like these that made Pope Francis a respected voice on climate change, with many praising his ability to drive collective action across divides. He will be remembered for his moral leadership that bridged the gap between the interconnected issues of poverty, climate adaptation and the consequences of human-caused global warming.

No comments:

Post a Comment