“Ensnared” and “Manipulated”: Official Statement by Valéria Chomsky Regarding Jeffrey Epstein

Valéria and Noam, 2014. Image Wikipedia.

As many are aware, my husband, Noam Chomsky, now 97, is confronting significant health challenges after suffering a devastating stroke in June 2023. Currently, Noam is under 24/7 medical care and is completely unable to speak or engage in public discourse.

Since this health crisis, I have been entirely absorbed in Noam’s treatment and recovery, solely responsible for him and his medical treatment. Noam and I don’t have any kind of public relations assistance. For this reason, only now have I been able to address the matter of our contacts with Jeffrey Epstein.

Noam and I have felt a profound weight regarding the unresolved questions surrounding our past interactions with Epstein. We do not wish to leave this chapter shrouded in ambiguity.

Throughout his life, Noam has insisted that intellectuals have a responsibility to speak the truth and expose lies — especially when those truths are uncomfortable to themselves.

As is widely known, one of Noam’s characteristics is to believe in the good faith of people. Noam’s overly trust[ing] nature, in this specific case, led to severe poor judgment on both our parts.

Questions have rightly been raised about Noam’s meetings with Epstein, and about administrative assistance his office provided regarding a private financial matter—one that had absolutely no relation to any of Epstein’s criminal conduct.

Noam and I were introduced to Epstein at the same time, during one of Noam’s professional events in 2015, when Epstein’s 2008 conviction in the State of Florida was known by very few people, while most of the public – including Noam and I – was unaware of it. That only changed after the November 2018 report by the Miami Herald.

When we were introduced to Epstein, he presented himself as a philanthropist of science and a financial expert. By presenting himself this way, Epstein gained Noam’s attention, and they began corresponding. Unknowingly, we opened a door to a Trojan horse.

Epstein began to encircle Noam, sending gifts and creating opportunities for interesting discussions in areas Noam has been working on extensively. We regret that we did not perceive this as a strategy to ensnare us and to try to undermine the causes Noam stands for.

We had lunch, at Epstein’s ranch, once, in connection with a professional event; we attended dinners at his townhouse in Manhattan and stayed a few times in an apartment he offered when we visited New York City. We also visited Epstein’s Paris apartment one afternoon for the occasion of a work trip. In all cases, these visits were related to Noam’s professional commitments. We never went to his island or knew about anything that happened there.

We attended social meetings, lunches, and dinners where Epstein was present and academic matters were discussed. We never witnessed any inappropriate, criminal, or reproachable behavior from Epstein or others. At no time did we see children or underage individuals present.

Epstein proposed meetings between Noam and figures that Noam had interest in, due to their different perspectives on themes related to Noam’s work and thought. It was in this academic context that Noam wrote a letter of recommendation.

Noam’s email to Epstein, in which Epstein sought advice about the press, should be read in context. Epstein had claimed to Noam that he [Epstein] was being unfairly persecuted, and Noam spoke from his own experience in political controversies with the media. Epstein created a manipulative narrative about his case, which Noam, in good faith, believed in. It is now clear that it was all orchestrated, having as, at least, one of Epstein’s intentions to try to have someone like Noam repairing Epstein’s reputation by association.

Noam’s criticism was never directed at the women’s movement; on the contrary, he has always supported gender equity and women’s rights. What happened was that Epstein took advantage of Noam’s public criticism towards what came to be known as “cancel culture” to present himself as a victim of it.

Only after Epstein’s second arrest in [July] 2019 did we learn the full extent and gravity of what were then accusations—and are now confirmed—heinous crimes against women and children. We were careless in not thoroughly researching his background. This was a grave mistake, and for that lapse in judgment, I apologize on behalf of both of us. Noam shared with me, before his stroke, that he felt the same way.

In 2023, Noam’s initial public response to inquiries about Epstein failed to adequately acknowledge the gravity of Epstein’s crimes and the enduring pain of his victims, primarily because Noam took it as obvious that he condemned such crimes. However, a firm and explicit stance on such matters is always required.

It was deeply disturbing for both of us to realize we had engaged with someone who presented as a helpful friend but led a hidden life of criminal, inhumane, and perverted acts.

Since the revelation of the extent of his crimes, we have been shocked.

In order to clarify the check: Epstein asked Noam to develop a linguistic challenge that Epstein wished to establish as a regular prize. Noam worked on it, and Epstein sent a check for US$20,000 as payment. Epstein’s office contacted me to arrange for the check to be sent to our home address.

Regarding the reported transfer of approximately $270,000, I must clarify that these were entirely Noam’s own funds. At the time, Noam had identified inconsistencies in his retirement resources that threatened his economic independence and caused him great distress. Epstein offered technical assistance to resolve this specific situation.

On this matter, Epstein acted accordingly, recovering the funds for Noam, in a display of help and very likely as part of a machination to gain greater access to Noam. Epstein acted solely as a financial advisor for this specific matter. To the best of my knowledge, Epstein never had access to our bank or investment accounts.

It is also important to clarify that Noam and I never had any investments with Epstein or his office—individually or as a couple.

I hope this retrospectively clarifies and explains Noam Chomsky’s interactions with Epstein. Noam and I recognize the gravity of Jeffrey Epstein’s crimes and the profound suffering of his victims. Nothing in this statement is intended to minimize that suffering, and we express our unrestricted solidarity with the victims.

This is a follow up post to, “A Response To Greg Grandin’s Chomsky-Epstein Article” published on Feb 6, 2026.

Valeria Chomsky’s statement on the Chomsky Epstein saga is out, and should confirm what any rational person should have known. The Chomskys did not know about Epstein’s horrific crimes until after his arrest, and when they did realize the magnitude of the crimes, they were as horrified as any of us. The Chomskys were responsible for poor judgment, and apologized for it.

A few additional points are worth bringing up. The Chomskys were not uniquely responsible for poor judgment. The entire scientific community that Chomsky was a part of trusted Epstein, as this email from Chomsky in 2023 makes clear.

Given these clarifications, all the takes about Chomsky-Epstein, including Grandin’s addendum, appear in particularly bad faith now. No one accounted for the possibility that Chomsky simply did not know about Epstein’s crimes at the time of his relationship with Epstein, and changed his mind as soon as he did know. Every single take was written as though Chomsky’s emails were written in public with no subsequent retraction.

Issues and knowledge often take time to crystallize. We know this in other cases. Not all Palestine activists concluded that what was happening in Gaza was a genocide at the same instant. The consciousness over genocide developed over a fairly long period of time. Would we really want a culture where those who came to the realization sooner start shaming those who came to the realization later, and that too based on what they say in private?

There is also more to say on the broader topic of civil liberties. It is worth re-reading Chomsky’s comments on the Faurisson affair: “it is a truism, hardly deserving discussion, that the defense of the right of free expression is not restricted to ideas one approves of, and that it is precisely in the case of ideas found most offensive that these rights must be most vigorously defended.” In my view, a similar logic holds for due process and civil liberties more broadly. They must be defended even when we are discussing horrific crimes like pedophilia. If we let the horror of the crimes allow us to play fast and loose with civil liberties, then it just opens the door for eroding civil liberties broadly, for the rest of us.

At the very least, this requires us to separate a defence of due process and civil liberties from a defence of the underlying crimes. To his credit, Grandin recognizes this elementary point in at least one place in his article by noting that “Chomsky doesn’t deny Epstein’s crimes, defend Epstein’s actions, or argue that they are exaggerated.” The point is more general. The ACLU is

known to have defended the free speech rights of groups advocating pedophelia in the abstract. This would almost certainly have consisted of the ACLU advising said groups about how to present themselves, if needed, even in the public. In other words, the ACLU probably provided PR advice to monsters. But it doesn’t follow that the ACLU is endorsing them.

The process of eroding civil liberties in the context of the Epstein issue is happening right now. We see it with the cavalier attitude with which privacy is being treated when scouring the Epstein files. For instance, an otherwise careful (and excellent) commentator like Adam Johnson tweets that: “The thing is I’m sensitive to the potential that incidental or tangential contact with Epstein can unduly smear people’s names but the reality is this… hasn’t happened. And the newsworthiness of his friendly chit chats with Musk, Gates, Chomsky etc far outweighed this risk” Thus, for instance, it is apparently acceptable to breach details of Chomsky’s financial dispute with his children. The premise of the tweet is illuminating. Apparently, one may have an expectation of privacy, but if the person one is communicating with is convicted of a criminal offence in the future, then all bets are off.

Incidentally, I can cook up lots of reasons why scouring Adam Johnson’s private emails (and that of other commentators) might be of public interest. I’d like to learn more about how sexism and racism underpin the private lives of leftists, and also whether the way they raise their children is aligned with progressive values. I wonder how Johnson feels about that.

The point of this is not to argue against the “Epstein Transparency Act”. There may well be reasons that justify the privacy breach. But it is important to acknowledge that the breach is real. Having a cavalier attitude about it and the broader attempt to pursue guilt by association indicates that there is clearly a massive need for basic education of elementary civil liberties within the left. Chomsky was wrong in one respect in his note on Faurisson – he lamented the authoritarianism of French intellectuals. American intellectuals in 2026 are not much better.

It is undeniable that Chomsky’s email merits criticism, and Valeria Chomsky’s note is correct to strike an apologetic tone. But there never was and isn’t any justification for the blood-lust and viciousness of the attacks on Chomsky, often by alleged leftists. I hope they take a good look at themselves.

The recent release of emails and photos revealing new details about Noam Chomsky’s relationship with convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein has sparked controversy across the political spectrum.

Conservative and liberal outlets alike have used the photos to suggest one of the left’s most influential intellectuals was “rotten all along,” while many on the left, including myself, have felt surprise and disappointment that Chomsky would associate with someone so morally reprehensible.

But beneath the sensational headlines and photos circulating online without context lies a more complex story—one that demands we distinguish between actual evidence of wrongdoing and politically motivated character assassination.

As someone who has devoted decades to exposing American war crimes, corporate power, and the propaganda systems that sustain them, Chomsky deserves better than trial by association.

The evidence released thus far, while certainly worthy of critical examination, falls far short of implicating Chomsky in Epstein’s crimes or even suggesting he possessed knowledge of Epstein’s predatory behavior during their association.

As William Pettus writes, “The attacks say far more about the political moment than about him. His life’s work was built on the idea that power seeks to discredit critics not by refuting arguments, but by contaminating reputations. What’s happening now follows that pattern almost perfectly.”

The Facts of the Relationship

Let’s begin by establishing what the documentary record actually shows. According to emails and documents released by the House Oversight Committee, Chomsky and his wife Valéria were introduced to Epstein in 2015 “during one of Noam’s professional events,” according to Valéria Chomsky’s February 2026 statement. However, a letter attributed to Chomsky and found in Epstein’s files—likely written in 2017 or later, when Chomsky was at the University of Arizona—states that he met Epstein “about six years prior” and had “regular contact since,” which would point to roughly 2011. This discrepancy may reflect the difference between a brief initial introduction and the beginning of substantive correspondence—or simply the imprecision of memory.

What is clear from the correspondence is that from roughly 2015 through early 2019, they maintained periodic contact, discussing topics ranging from global finance and artificial intelligence to Middle Eastern politics and linguistics.

The documents also describe Epstein acting as a facilitator. Epstein reportedly arranged a call with a Norwegian diplomat involved in the Oslo Accords and helped arrange a meeting with former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak, a figure Chomsky had written about critically. Epstein also offered Chomsky access to his residences in New York and New Mexico.

The association went beyond professional contact. As Valéria writes in her statement:

“We had lunch, at Epstein’s ranch, once, in connection with a professional event; we attended dinners at his townhouse in Manhattan and stayed a few times in an apartment he offered when we visited New York City. We also visited Epstein’s Paris apartment one afternoon for the occasion of a work trip. In all cases, these visits were related to Noam’s professional commitments. We never went to his island or knew about anything that happened there.”

She adds:

“We attended social meetings, lunches, and dinners where Epstein was present and academic matters were discussed. We never witnessed any inappropriate, criminal, or reproachable behavior from Epstein or others. At no time did we see children or underage individuals present.”

On the question of how the relationship began, Valéria describes what amounts to a deliberate courtship:

“When we were introduced to Epstein, he presented himself as a philanthropist of science and a financial expert. By presenting himself this way, Epstein gained Noam’s attention, and they began corresponding. Unknowingly, we opened a door to a Trojan horse. Epstein began to encircle Noam, sending gifts and creating opportunities for interesting discussions in areas Noam has been working on extensively.”

There was also a financial dimension to the relationship. In March 2018, approximately $270,000 was transferred to Chomsky from an account associated with Epstein. Valéria’s statement clarifies:

“These were entirely Noam’s own funds. At the time, Noam had identified inconsistencies in his retirement resources that threatened his economic independence and caused him great distress. Epstein offered technical assistance to resolve this specific situation.”

She adds that “Epstein acted solely as a financial advisor for this specific matter” and that “Noam and I never had any investments with Epstein or his office—individually or as a couple.”

Valéria also reveals a previously unknown $20,000 payment: “Epstein asked Noam to develop a linguistic challenge that Epstein wished to establish as a regular prize. Noam worked on it, and Epstein sent a check for US$20,000 as payment.”

The email record and Valéria’s own description of Epstein as “a very dear friend” in a 2019 email to Steve Bannon suggests the relationship went beyond a purely professional or transactional association—though as one careful reader of the full email archive observed “the entire relationship develops around two trusts” that Noam had set up with his first wife Carol, and the painful family dispute that followed her death.

In this reading, Epstein’s helpfulness during what Chomsky described as “the worst thing that’s ever happened to me”—a bitter financial conflict with his own children over inheritance—explains much of the apparent warmth. Epstein was, by multiple accounts, “extremely helpful” throughout this crisis, and “the occasional dinners and side conversations are marginal in comparison to financial matters.”

This doesn’t excuse the association, but it provides important context for understanding how Epstein—who spent millions cultivating relationships with academics and public figures—was able to embed himself in Chomsky’s life at a moment of profound personal vulnerability.

The Letter of Recommendation

One of the most discussed documents in the release is an undated letter addressed “To whom it may concern” that praises Epstein effusively, describing his “limitless curiosity, extensive knowledge, penetrating insights, and thoughtful appraisals” and calling him “a highly valued friend and regular source of intellectual exchange and stimulation.”

When this letter first surfaced, many—including Greg Grandin in The Nation, Norman Finkelstein, Jennifer Loewenstein, and myself—questioned its authenticity, noting the absence of a signature, university letterhead, or any record of Chomsky sending it, and suggesting the language didn’t sound like him.

Valéria’s statement, however, confirms that Chomsky did write it: “Epstein proposed meetings between Noam and figures that Noam had interest in, due to their different perspectives on themes related to Noam’s work and thought. It was in this academic context that Noam wrote a letter of recommendation.”

The letter is disappointing, though Valéria’s framing suggests it was written as a professional courtesy within what Chomsky understood to be an academic context. It remains an example of precisely the kind of poor judgment this article as a whole explores—the willingness to extend generosity and trust without sufficient scrutiny.

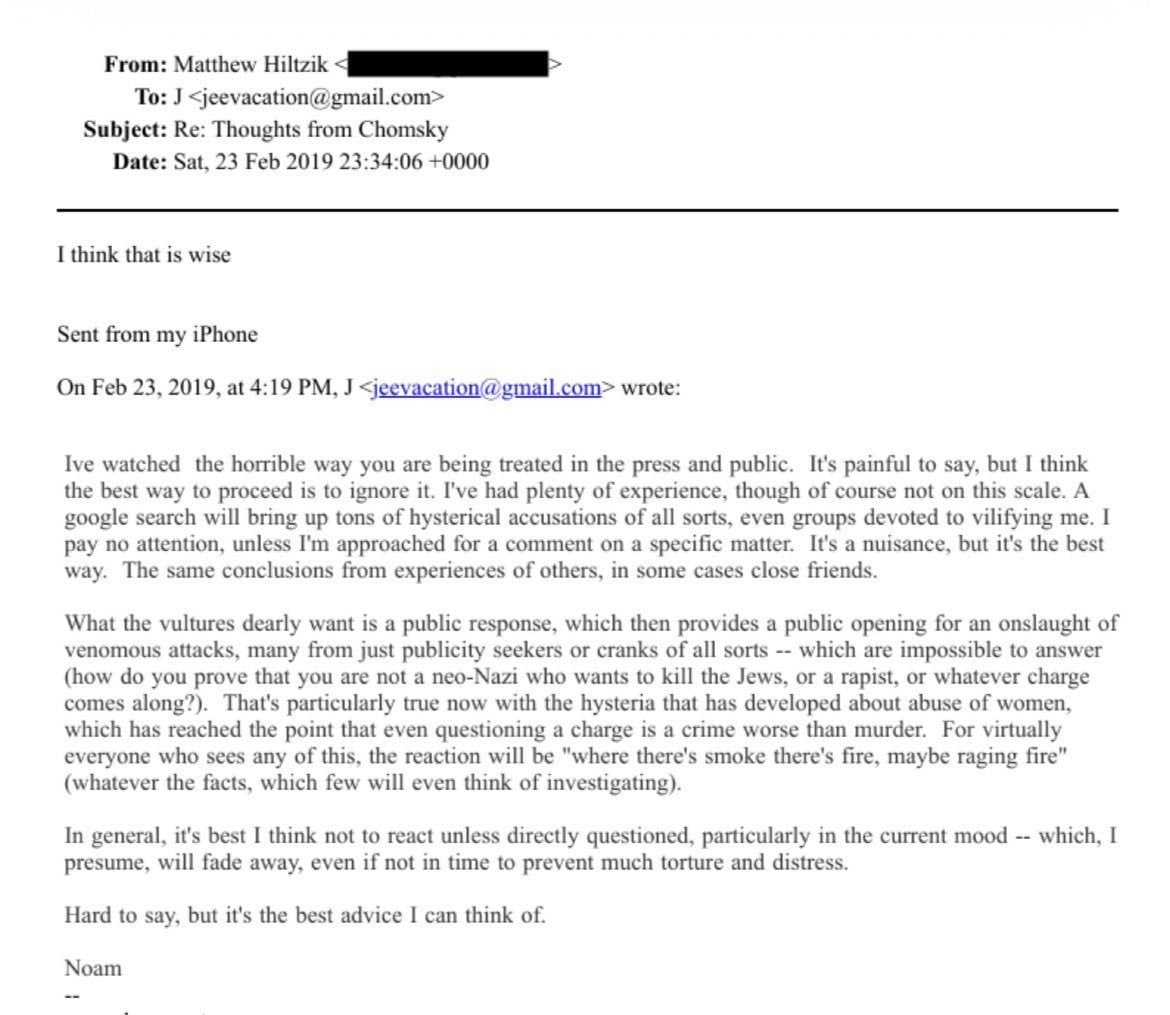

The “Advice” Email (February 2019)

The most troubling revelation from the newly released files is an exchange from February 23, 2019—three months after the Miami Herald published Julie K. Brown’s exposé detailing how Epstein had operated a transatlantic sex trafficking network targeting children and young girls. In this exchange, Epstein wrote to Chomsky asking for advice on handling his “putrid press,” which was “spiralling out of control.”

As Greg Grandin reports in The Nation, Chomsky responded the same day, sympathetically. He urged Epstein to ignore the news and not to comment. Chomsky’s response referenced his own experience dealing with public vilification: “A google search will bring up tons of hysterical accusations of all sorts, even groups devoted to vilifying me… venomous attacks, many from just publicity seekers or cranks of all sorts.” He then referenced #MeToo and “the hysteria that has developed about abuse of women, which has reached the point that even questioning a charge is a crime worse than murder.”

This is, to put it plainly, awful to read.

Even under the most charitable interpretation, Chomsky was treating the well-documented accusations against a sex trafficker as analogous to the bad-faith political smears he’d endured throughout his own career. The comparison is stomach-churning—and it represents a profound failure of the moral imagination Chomsky spent his career applying to geopolitics.

Valéria addresses this directly in her statement: “Epstein had claimed to Noam that he [Epstein] was being unfairly persecuted, and Noam spoke from his own experience in political controversies with the media. Epstein created a manipulative narrative about his case, which Noam, in good faith, believed in.”

She adds an important clarification:

“Noam’s criticism was never directed at the women’s movement; on the contrary, he has always supported gender equity and women’s rights. What happened was that Epstein took advantage of Noam’s public criticism towards what came to be known as ‘cancel culture’ to present himself as a victim of it.”

There is some supporting evidence for this framing.

In late 2018, Epstein sent Chomsky a draft op‑ed giving a detailed, lawyerly defense of his 2008 case, arguing among other things that state prosecutors had weighed “exculpatory evidence, including sworn testimony from many that they lied about being eighteen years old.” Chomsky replied that this was “a powerful and convincing statement.”

In other words, Epstein gave Chomsky a version of events that played directly to his existing biases—and Chomsky bought it. As Valéria writes, “One of Noam’s characteristics is to believe in the good faith of people. Noam’s overly trusting nature, in this specific case, led to severe poor judgment on both our parts.”

This doesn’t excuse Chomsky’s response, but it does help explain how it happened. A man who spent decades scrutinizing state power and media narratives was susceptible to having those same instincts weaponized against him by a skilled manipulator. As Grandin observes, Chomsky “reflexively treats emotionally wrenching matters as if they can be defused through adherence to abstract principles.”

With Faurisson, it was free speech. With Epstein, it was due process and the presumption of unfair persecution. In both cases, the rigid application of principle blinded him to the moral stakes.

It’s also worth noting that Chomsky’s record on these issues is more complicated than the 2019 email alone suggests. In interviews, he has spoken forcefully against pornography as “humiliation and degradation of women,” comparing it to sweatshop labor and child abuse.

When an interviewer asked how the conditions of pornography should be improved, Chomsky replied: “Just like child abuse, you don’t want to make it better child abuse, you want to stop child abuse. Suppose there’s a starving child in the slums, and you say ‘well, I’ll give you food if you’ll let me abuse you’… is that an argument? The answer to that is stop the conditions in which the child is starving, and the same is true here. Eliminate the conditions in which women can’t get decent jobs, not permit abusive and destructive behavior.”

He has said of the #MeToo movement that it “grows out of a real and serious and deep problem of social pathology” that “has exposed it and brought it to attention,” while cautioning about “confusing allegation with demonstrated action.” These are not the views of someone indifferent to the exploitation of women—but they are the views of someone whose rigid commitment to procedural principle could be exploited by a sophisticated predator.

The best-faith reading is that Chomsky was in genuine denial about the accusations, seeing them through the prism of his own experience with decades of bad-faith smears. His close friendship with Lawrence Krauss—a physicist who faced sexual harassment allegations—may have further reinforced his instinct to be skeptical of such accusations within his social circle. But his total lack of empathy in the email, and his flippant dismissal of what the Miami Herald had by that point thoroughly documented, warrants serious criticism.

His later correspondence suggests he did eventually acknowledge the gravity of Epstein’s crimes (discussed in the next section). But his refusal to publicly denounce Epstein, even after the full scope of the crimes became clear, and the defensive posture he and Valéria maintained until her February 2026 statement, has already burned through a great deal of the good will he once had among millions.

In fairness, Chomsky’s silence on Epstein is consistent with a lifelong pattern. As he wrote in one exchange:

“I don’t recall a statement ever denouncing anyone, even the worst mass murderers. When the question comes up I condemn the crimes—though usually I am reluctant to hop on bandwagons and join the crowd. Nixon was a monster, but when it became fashionable to denounce him, I didn’t join.”

The Chomsky family was also famously private—Noam and Valéria consistently guarded their personal lives and rarely engaged with public controversies on a personal level. These are understandable traits in context, but context is something the vast majority of people will never dig deep enough to find. Most will see the headlines, the photo on the plane, the “hysteria” quote—and draw reasonable conclusions from incomplete information. That’s a consequence Chomsky brought on himself, however unintentionally.

To what degree Valéria’s explanation will work to restore that good will, time will tell.

What Chomsky Actually Knew

The central question is what Chomsky knew, and when. Here the record presents a genuine tension.

Valéria’s statement claims they were unaware of Epstein’s 2008 conviction until the Miami Herald’s November 2018 investigation:

“Noam and I were introduced to Epstein at the same time, during one of Noam’s professional events in 2015, when Epstein’s 2008 conviction in the State of Florida was known by very few people, while most of the public – including Noam and I – was unaware of it.”

But when Chomsky was asked about his relationship with Epstein in 2023, he told The Wall Street Journal:

“Like all of those in Cambridge who met and knew him, we knew that he had been convicted and served his time, which means that he re-enters society under prevailing norms — which, it is true, are rejected by the far right in the US and sometimes by unscrupulous employers… I’ve had no pause about close friends who spent many years in prison, and were released. That’s quite normal in free societies.”

These two accounts are difficult to fully reconcile. It’s possible Chomsky learned of the conviction at some point between 2015 and 2018 without it registering as disqualifying. It’s also possible Valéria’s recollection—written three years after his stroke—reflects an honest reconstruction rather than a precise timeline. What seems clear is that by the time Chomsky gave advice to Epstein in February 2019, he was aware of both the conviction and the Herald’s reporting, yet remained skeptical of the accusations.

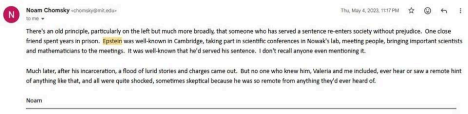

Since first publishing this piece, a reader forwarded an email exchange he had with Chomsky about Epstein, shared here with permission. Chomsky’s response, dated May 4, 2023, provides important insight into his reasoning:

“There’s an old principle, particularly on the left but much more broadly, that someone who has served a sentence re-enters society without prejudice. One close friend spent years in prison. Epstein was well-known in Cambridge, taking part in scientific conferences in Nowak’s lab, meeting people, bringing important scientists and mathematicians to the meetings. It was well-known that he’d served his sentence. I don’t recall anyone even mentioning it.

Much later, after his incarceration, a flood of lurid stories and charges came out. But no one who knew him, Valeria and me included, ever [heard] or saw a remote hint of anything like that, and all were quite shocked, sometimes skeptical because he was so remote from anything they’d ever heard of.”

As Jennifer Loewenstein has explained, the general public during 2008-2017 knew only that Epstein had been convicted of solicitation of prostitution and procurement of a minor for prostitution, and served 13 months. What they didn’t know was that behind this lenient arrangement was a secret sweetheart deal, and that the victims’ evidence had been “effectively dismissed by higher-ups in Florida and Washington.”

Research into the media record during this period supports the claim that the New York Times—Chomsky’s primary newspaper—largely whitewashed and suppressed the story of Epstein’s rigged prison sentence, despite extensive reporting in the local Palm Beach Post. MIT faculty who interacted with Epstein similarly did not disclose his criminal record when accepting donations, which facilitated the initial connections.

The full extent of Epstein’s sex trafficking operation and the systematic nature of his abuse of children only became widely known after the Miami Herald’s November 2018 investigation by Julie K. Brown, which led to Epstein’s 2019 arrest on federal sex trafficking charges.

“He Knew Epstein Was a Registered Sex Offender”

One of the most common and understandable criticisms I’ve received since first publishing this piece is: “Chomsky knew Epstein was a convicted sex offender and didn’t care. He associated with him anyway. That alone is disqualifying.”

The timeline is complicated by the tension between Valéria’s claim that they were unaware of the conviction until 2018 and Chomsky’s own 2023 statements suggesting he did know. Whether the reintegration principle was being applied consciously from the start or only after learning about the conviction later, it is clear that by 2018-2019, Chomsky was making a deliberate choice to maintain the relationship with full knowledge.

In response, Chomsky’s critics suggest there’s only one obvious moral stance, and that those who choose otherwise must not care about victims or, worse, condone such behavior. But the question it raises—what obligations we have toward people who’ve served their sentences—reveal legitimate disagreements in society that reflect differing views on punitive versus restorative justice.

View 1: Certain crimes—particularly sex crimes—warrant permanent social exile regardless of legal consequences served. Association with such individuals, even years after release, reflects moral failure, indifference to victims, or social acceptance of their crimes.

View 2: People who serve court-ordered sentences deserve a path back to civil society. Permanent exile creates a permanent underclass and undermines any notion of rehabilitation. This principle applies even when we find the crime abhorrent and the punishment inadequate, because the goal is to support reintegration.

Chomsky has consistently held View 2. And it is worth noting that research on sex offender recidivism actually supports the idea that “positive social relationships actually lower recidivism rates,” and that “familial relationships and social support have greater power over human behavior than sanctions, restrictions, and punishments.”

In the same 2023 email exchange provided to me by a reader, Chomsky spoke to his support of View 2:

“It used to be a truism on the left that all of us have the potential to be saints or sinners. It’s not an innate disposition. Circumstances, upbringing, social norms, all sorts of things enter into good and bad behavior. That’s why the left always stressed the need for efforts for rehabilitation. By now it’s virtually gone. In the US at least.”

From this perspective, abandoning the principle because it catastrophically failed in one case means accepting permanent exile for entire categories of offenders—regardless of what work they’ve done toward genuine accountability.

Critics counter that someone who spent a career scrutinizing how power protects itself should have been more skeptical when encountering a wealthy financier with a sex offense conviction. That’s a fair point. But demanding he investigate everyone’s rehabilitation status before professional engagement sets an impossible standard—he’s spoken with war criminals, corporate executives, and government officials responsible for mass deaths without vetting their moral transformation. We also know Epstein was spending millions of dollars to infiltrate academic circles to ensure he appeared respectable and reformed.

As Valéria concludes:

“We were careless in not thoroughly researching his background. This was a grave mistake, and for that lapse in judgment, I apologize on behalf of both of us. Noam shared with me, before his stroke, that he felt the same way.”

She adds:

“In 2023, Noam’s initial public response to inquiries about Epstein failed to adequately acknowledge the gravity of Epstein’s crimes and the enduring pain of his victims, primarily because Noam took it as obvious that he condemned such crimes. However, a firm and explicit stance on such matters is always required.”

Reasonable people can disagree about whether the reintegration principle should apply to sex offenders, whether Chomsky applied it with sufficient scrutiny, and whether this level of contact was appropriate. What the evidence doesn’t support, regardless of which view one holds, is the claim that Chomsky was knowingly complicit in Epstein’s crimes.

Steve Bannon & The Old School Principle of Talking to Everyone

When asked if he regretted his association with Epstein, Chomsky responded:

“I’ve met [all] sorts of people, including major war criminals. I don’t regret having met any of them.”

This principle can be seen throughout his life.

As Grandin writes in The Nation, Chomsky “earned a reputation early in his career as someone whose door was always open—who talked to anyone who knocked and answered any letter delivered.” When email arrived at MIT in the mid-1980s, “the stream of letters Chomsky received was largely replaced by a torrent of e-mails. But Chomsky’s open-door policy continued. He still felt obligated to answer all, or nearly all, the people who wrote him.”

Norman Finkelstein commented on this: “It is an incontrovertible fact that Professor Chomsky met and corresponded with everyone. He didn’t discriminate; that was his modus operandi. That disposes of the bulk of the accusations leveled against Professor Chomsky.”

And as Bev Stohl, Chomsky’s office secretary for 24 years, recounted in her memoir, his inability to say no was perhaps his defining personal flaw:

“‘I don’t know why people don’t hear no when I write to them,’ was Noam’s frequent lament… He had debated William F. Buckley, Jean Piaget, Michel Foucault, and B.F. Skinner without breaking a discernable sweat, but preferred that I be the naysayer, the killjoy to the inquiring public, I think because of his ambivalence. He hated saying no.”

This openness extended across the political spectrum—including, as recently released documents show, to Steve Bannon. A photo of Chomsky and Bannon was found in Epstein’s files, and there’s evidence Epstein tried to arrange a Bannon interview with Chomsky for a never-finished documentary meant to rehabilitate Epstein’s image.

Michael Albert, who has worked alongside Chomsky for decades and co-founded Z Magazine, commented on this in his piece, “Chomsky Reassessed?“:

“You may wonder, why would Noam actually want to talk to Bannon, for example, if in his proximity? Or to Epstein?

Explanation one: he admired Bannon and Epstein and wanted to aid them or he even just enjoyed being around such people.

Explanation two: He was curious and given the chance he wanted to learn things useful to his work of dismantling lies and violence. When face-to-face, even with the Devil, Noam would be civil. It was his way. So I admit that I find it hard to fathom why explanation one beats out explanation two, given the existence of Noam’s history.”

A Question of Proportion

The question isn’t whether Epstein deserved harsher consequences than his 2008 sweetheart plea deal—he absolutely did, and his subsequent crimes warranted life in prison. The failure of prosecutors to charge him appropriately represents a massive injustice to his victims.

But here’s the central question: Should Chomsky be condemned for associating with Epstein during a period when Epstein was not yet a social pariah, when numerous faculty and staff at MIT were using his financial services, when he was still being invited to academic conferences and hosting dinners with scientists and intellectuals, and when the full scope of his crimes remained sealed from public view?

Bill Gates met with Epstein repeatedly after his conviction, even staying at his mansion. Dozens of academics and scientists accepted his funding and attended his gatherings. MIT’s Media Lab took his donations and hosted him for nine visits between 2013 and 2017, while Harvard gave him a personal office, a key card, and hosted him for more than 40 documented visits.

Collectively, hundreds of men and women in respected academic circles associated with Epstein, post-2008 conviction. Yet the media treatment of these associations has largely been “errors in judgment” or “unfortunate lapses.”

Chomsky, by contrast, faces calls for wholesale delegitimization of his life’s work—a response his longtime friends and colleagues find both disproportionate and disconnected from the actual facts.

We should remember that Epstein’s public legitimacy depended on appearing reformed, credible and respectable in the circles Chomsky frequented. That’s no doubt why Epstein would have focused on building relationships with Chomsky and other luminary figures and diplomats, to insulate him from potential scrutiny.

As Valéria writes:

“It is now clear that it was all orchestrated, having as, at least, one of Epstein’s intentions to try to have someone like Noam repairing Epstein’s reputation by association.”

[…]

“It was deeply disturbing for both of us to realize we had engaged with someone who presented as a helpful friend but led a hidden life of criminal, inhumane, and perverted acts.”

What the Record Doesn’t Show

Here’s what the evidence doesn’t establish:

- Any evidence Chomsky knew about or participated in Epstein’s sex crimes

- Any evidence Chomsky received money directly from Epstein (the $270,000 was his own funds; the $20,000 was payment for work)

- Any evidence Chomsky was at locations where abuse occurred

- Any victim testimony implicating Chomsky

- Any evidence Chomsky provided material support for Epstein’s criminal activities

As the Epstein Web Tracker (an independent documentation project) concludes: “A name in a document is not proof of a crime. Being on a calendar or guest list shows contact, not guilt. Context matters. A scheduled dinner or intellectual meeting belongs in a different category than a wire-transfer record or a co-ownership filing for a shell company.”

The Political Function of This Scandal

It’s worth asking who benefits from the Chomsky-Epstein scandal. Chomsky has spent his career arguing that American presidents are war criminals, that capitalism is fundamentally exploitative, and that mainstream media manufactures consent for elite interests. He is, in short, a figure the establishment has every reason to want discredited.

The Epstein scandal provides the perfect vehicle: guilt by association dressed up as moral reckoning. It allows critics to avoid engaging with Chomsky’s actual arguments about power, imperialism, and propaganda while casting him as a hypocrite who consorted with the very elites he claimed to oppose.

But this critique fundamentally misunderstands Chomsky’s project.

He has never argued that intellectuals should refuse to speak with powerful people or that we should create a cordon sanitaire around anyone who has committed crimes. On the contrary, his entire method has been to understand how power works by engaging directly with those who wield it, analyzing their justifications, and exposing the contradictions between their rhetoric and their actions.

An astute question to this, I’ve seen, is that if Noam engaged with radioactive figures for research purposes, where are his published findings (about Bannon, for instance)? But from what I’ve learned, Noam didn’t feel obligated to write about every single individual he encountered. Noam was more focused on systems and big picture issues over individuals. I think his experiences contributed to his ever evolving understanding of the world, which then fed into his wider work.

“Not long after he was photographed with Steve Bannon,” Greg Grandin writes, “Chomsky gave a speech at Boston’s Old South Church denouncing Bannon as ‘the impresario’ of an ‘ultranationalist, reactionary international’ movement.”

Grandin concludes in his well-researched and recommended piece, “Chomsky was not a sentimental member of what Giridharadas calls the ‘Epstein Class.'”

His Life’s Work Still Stands

Whatever one makes of Chomsky’s relationship with Epstein, I don’t believe it should overshadow the monumental contributions he has made to our understanding of power, propaganda, imperialism, and corporate capitalism. His work on:

- Manufacturing Consent and the propaganda model of media

- The Pentagon Papers and Vietnam War crimes

- East Timor and Indonesia’s U.S.-backed genocide

- Central America and Reagan’s terrorist campaigns

- The Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- Neoliberalism and corporate power

- Linguistic theory and cognitive science

…has shaped multiple generations of scholars, activists, and journalists. These contributions don’t evaporate because he acted according to principles he’s held throughout his life—despite those principles failing him in this case.

Here’s Where I Land

I want to be clear: I’m not arguing Chomsky made the right call in maintaining a relationship with Epstein.

His lack of a forceful condemnation of Epstein before his stroke is undeniably disappointing.

The February 2019 “advice” email is indefensible in its tone, even if the underlying intent was to counsel a person he believed—naively, wrongly—was being unfairly persecuted. And Valéria’s confirmation that Chomsky wrote the letter of recommendation, in language far more effusive than the relationship warranted, only adds to the picture of poor judgment.

But what I am arguing is that:

- The evidence released thus far does not implicate Chomsky or his wife in Epstein’s crimes or suggest they had knowledge of Epstein’s predatory behavior during their association.

- Valéria’s statement—which acknowledges “severe poor judgment on both our parts,” apologizes for their “grave mistake,” and expresses “unrestricted solidarity with the victims”—represents the kind of honest reckoning that has been missing from this story.

- There is no evidence “Chomsky didn’t care about the victims” or saw Epstein’s crimes as “not a big deal.” His disposition reflects debatable but legitimate differences on the left about reintegration norms—combined with a catastrophic failure to apply the same skepticism toward Epstein that he applied to power structures throughout his career. As Michael Albert, a long-time colleague attests: “I am confident that Noam’s hate for sexism, misogyny, racism, exploitation and fascism didn’t lose even a tiny fraction of its passion and clarity due to his ‘time spent with’ Epstein and/or Bannon. Just like his understanding of the American political system didn’t somehow disappear when he said we should vote for the lessor evil in swing states. And just like his compassion for victims of Nazism didn’t diminish when he defended Faurisson’s free speech.”

- We can debate and critique Chomsky’s association with Epstein—and his genuinely troubling February 2019 email—without participating in what is essentially a politically motivated smear campaign.

- I believe criticism of Chomsky is absolutely warranted, and I’ve done my best to model what a fair and proportionate accountability process might look like for Noam, or any longtime ally to our movements. Aside from his disastrous failure of judgment with Epstein, even as the evidence piled up, his defensive public response was an entirely self-inflicted wound, which Valéria has since acknowledged. But that said, I don’t want to put his legacy on a pedestal or in the grave. If we insist our intellectual heroes be completely free from any serious mistakes, poor judgment calls, or ethical blind spots—we will have few heroes left, and find ourselves constantly disappointed. This standard also serves power perfectly: it ensures the public constantly purges its most effective voices over human fallibility while establishment figures face no comparable scrutiny.Chomsky has spent seven decades doing work most of us will never approach—documenting atrocities, exposing propaganda systems, standing against empire when it was deeply unpopular. We can hold complexity: acknowledging Chomsky’s failures while refusing to participate in his delegitimization. The alternative—treating any flaw as disqualifying—leaves us with few to learn from and no capacity to build the movements we desperately need.

- Part of what inspired me to write this article goes far beyond Chomsky. It is about the health of our movements and how we navigate tension and accountability for those that have made serious mistakes.This rush to discard movement leaders (or anyone in the struggle) over flawed judgments, serious mistakes or legitimate differences in perspective is not a new pattern on the left. Bernie Sanders has also been called a “sellout” and a “traitor” for endorsing Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden—strategic choices aimed at preventing worse outcomes. On the other end, Dr. Cornel West, long beloved by the left, was dismissed by many for running third party. Jill Stein is still exiled by millions for her choices. Kshama Sawant and others are rejected by many because of their campaign to ensure Kamala Harris lost to Trump as punishment for supporting the genocide in Gaza. I saw their campaign as an understandable but catastrophic strategic mistake, with immense consequences, but I still see her as a sister in the struggle, and Chomsky has been condemned for all number of statements and positions he’s made over his lifetime. I have strong disagreements with all of them, but I still consider them brothers and sisters in the struggle. As a student of Thich Nhat Hanh for 20 years, that is just my disposition.In my view, the left’s circular firing squad tendency too often treats any moral failure, legitimate disagreement or tactical compromise (or lack of it) within unjust systems as grounds for complete dismissal, erasing decades of contribution with alarming speed. This asymmetry of focus and attention isn’t accidental. It’s easier to tear down our own than to sustain the difficult work of building power against entrenched interests.

In Defense of Reasoned Disagreement

The evidence may change. More documents may be released that fundamentally alter our understanding of Chomsky’s relationship with Epstein. If and when that happens, we should reassess accordingly. But based on what we know now, these associations complicate his legacy, but don’t warrant the blanket condemnation he’s faced across the political spectrum.

I respect those that disagree, but in my book, Chomsky is still a legend—human, flaws and all.

His work exposing how elites manufacture consent for the status quo was instrumental in me becoming an activist and co-founding Films For Action.

I’ve never agreed with Chomsky on everything or revered him as infallible, but my respect for him or anyone has never depended on that. Nor Chris Hedges, Amy Goodman, Kshama Sawant, or Bernie Sanders. Nor activists in my community who I often disagree with.

One of the principles I learned from Chomsky’s work was how to engage with ideas I oppose: through reasoned argument rather than moral condemnation, by addressing the strongest version of an opponent’s case rather than caricaturing it, and by maintaining that people can disagree in good faith without being enemies. He modeled this even when dealing with his harshest critics—responding to their arguments rather than attacking their character.

Though a majority appears to appreciate my article, the critical responses so far have varied between thoughtful and harsh. Despite my critiques of Chomsky throughout the piece, my refusal to condemn him wholesale has been met with equally forceful condemnation.

Some critiques are quite uncharitable. Some deliberately misread my argument. Some admit they didn’t read the article at all. Others offer legitimately understandable counterarguments that I respect, which has helped me improve this article and my own thinking.

It’s that last category that matters. There are legitimate disagreements on the left about what Chomsky’s association with Epstein means and whether it’s disqualifying. The same goes for any number of his ideas and positions.

What I object to is the refusal to acknowledge that legitimate disagreement exists at all. The insistence that anyone who weighs this evidence differently must be defending sexual predation, or deserves to be dismissed with the same contempt they reserve for Chomsky himself. That pattern—treating moral complexity as moral failure, demanding unanimous condemnation as proof of virtue—is exactly what I’m critiquing.

It’s an old school ethic, one Chomsky practiced throughout his career, to maintain space for principled disagreement without resorting to character assassination.

We can argue vigorously about whether Chomsky’s judgment failed him (I agree it did), about what standards we should apply, about whether this episode undermines his legacy—and still treat each other as people attempting to navigate complex issues in good faith.

Against Hero Worship

One recurring criticism in left circles dismisses Chomsky as a “poor man’s Michael Parenti,” someone who didn’t lead the revolution, who sold out, who wasn’t radical enough. Similar attacks target Bernie Sanders for working within the Democratic Party, or dismiss any activist who doesn’t meet some imagined purity threshold.

This is ironically its own form of hero worship—just inverted. It assumes the only activists we should respect are those with the most radically uncompromising politics.

But here’s the thing: I’m actually doing the opposite of holding Noam on a pedestal. I don’t expect any single activist, intellectual, or politician to lead us to liberation. That’s not how change works, and placing that burden on individuals sets us up for endless cycles of disappointment and denunciation.

Instead, I appreciate contributions for what they are. Chomsky introduced millions of people to sophisticated critiques of power and manufacturing consent. That’s valuable. Bernie Sanders moved policy conversations leftward and inspired a generation of organizers. That’s valuable. Anarchists blockading pipelines risk their freedom to slow ecological collapse. That’s valuable. None of them are perfect. None of them will save us. All of them contribute something worth building on.

We never needed Chomsky or any movement figure like Michael Parenti, Kshama Sawant, Chris Hedges, Amy Goodman, Bernie Sanders, Cornel West, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, or anyone else to be a perfect avatar for our politics.

What we’ve always needed is millions of people to get off the sidelines and into the game, taking the best from these influences, learning from their mistakes and respecting a diversity of perspectives and contributions.

The rush to judge, not just Chomsky, but all of our movement leaders, reflects the same mistake as hero worship—just with the valence flipped. Both approaches treat individuals as either saints or frauds, saviors or sellouts, rather than as humans with mixed records whose work we can learn from while remaining clear-eyed about their limitations.

Real movements need many people contributing in different ways—some writing theory, some organizing unions, some running for office, some engaging in direct action, some building alternative institutions. Demanding that everyone pursue the most radical possible path, or dismissing anyone whose life doesn’t match an imaginary revolutionary ideal, doesn’t build power. It just ensures we keep eating our own while the actual structures of concentrated power remain untouched.

That serves power far more effectively than any of Chomsky’s mistakes ever could.

[LAST UPDATED 2/08/26]

Tim Hjersted is the director and co-founder of Films For Action, a library dedicated to the people building a more free, regenerative and democratic society

Lord Mandelson: Trapped in the Epstein Web

Photograph Source: Number 10 – Prime Minister Keir Starmer – OGL 3

Jeffrey Epstein certainly got around. He moved virally, galloping through the cells of the establishment. What was more, he was permitted to. Dead and buried, the financier, convicted paedophile, sex trafficker, eugenics follower, and the man all in power would want to know, continues to ruin reputations, casting doubt on many relationships, and stirring investigations into his correspondents.

Much of this damage is emanating from that noxious font of revelation, despair and disgrace hosted by the US Department of Justice, entitled the Epstein Library. As a result of these 3.5 million files or so, Noam Chomsky, saint of the progressive Left, may well find himself the poorer for his foolish correspondence sneering at “the hysteria that has developed about abuse of women”. Former US President Bill Clinton and his wife and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton have agreed to do filmed depositions for the House Committee on Oversight and Governance Reform. And in Britain, Lord Peter Mandelson, immodestly seeing himself as the creator of New Labour, finds himself facing potential criminal investigations in the UK and the European Union.

Mandelson’s case is particularly dire. Here was a person who had already lost his job in the cabinet twice over issues involving matters of money and the wealthy. In 1998, he resigned as trade and industry secretary after obtaining a loan of £373,000 from the Paymaster General, Geoffrey Robinson, to purchase a house. In 2001, he fell foul over a passport application from Indian billionaire Srichand Hinduja who had pledged £1m in sponsorship for the Millenium Dome project when Mandelson was in charge.

Despite a heavily blotted copybook, Mandelson still secured the confidence of Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer to be appointed ambassador to Washington in anticipation of the second Trump administration. The association between Mandelson and the late Epstein was already known, making the appointment dangerous in the extreme. The publication of certain emails revealing the continuing friendship post-conviction doomed yet another job.

The extent of that association is now becoming even more apparent. Now notorious for being a convicted paedophile, Epstein was receiving updates from Mandelson following the 2010 general election. (Mandelson had been politically revived as business secretary.) Seeing his hold on power slide, Prime Minister Gordon Brown was trying to secure a coalition with the Liberal Democrats. “GB now having ‘secret’ talks with [Lib Dem leader Nick] Clegg in Foreign Office,” Mandelson informs Epstein on May 9. On May 10, he again updates Epstein: “Finally got him to go today.”

Within hours Brown announced that he would be resigning as Labour leader but continuing as prime minister, a precondition demanded by Clegg in holding coalition talks. These came to naught, with Lib Dem leader preferring to share power with the Conservatives of David Cameron. But throughout, the Mandelson-Epstein exchanges take place, with the financier more than happy to offer morsels of wisdom. In one instance, Epstein suggests that the Liberal Democrat-Labour coalition would comprise “15m v 10 million votes”. This is then followed by another suggestion: “[W]hy not let tories govern with minority, no coalition”. In doing so, they would be unable to get “anything done”. Mandelson replies that this was unlikely “cos GB thinks British economy will collapse without [him] at helm.”

Epstein also proffers his view about Brown’s credibility as a continuing prime minister, informed by a certain “jess”. Supporting the Labour leader “will be seen as bad form commercially, he has lost the confidence of the public.” The views of investment bank JP Morgan are also given, they being “very concerned that the pound could be the next currency to falter. and big time. uncertainty not in your favour”.

Epstein also received what appears to be advanced notice of a 500 billion euro bailout intended to save the euro as the Greek economy was imploding. European finance ministers had rapidly concluded that the bailout was necessary to contain financial contagion in the eurozone. The night prior to the deal’s conclusion, the financier badgers Mandelson: “Sources tell me 500 b euro bailout, almost complete.” The reply: “Sd be announced tonight.” Mandelson promised to call after leaving 10 Downing Street.

The previous year, Mandelson had gleefully informed Epstein about asset sales and tax changes being considered by the Brown government. That conduct, and the broader disposition of Mandelson as business secretary to Epstein, has led the Metropolitan Police to commence an investigation. “Following this release and subsequent media reporting,” Metropolitan Police Commander Ella Marriot stated, “the Met has received a number of reports relating to alleged misconduct in public office. The reports will be reviewed to determine if they meet the criminal threshold for investigation.”

On February 3, Balazs Ujvari, a spokesperson of the European Commission, also revealed interest in investigating potential breaches, considering Mandelson’s time as European Commissioner for Trade. “We have rules in place emanating from the treaty and the code of conduct that commissioners, including former commissioners, have to follow.”

Epstein’s web is looking increasingly, and alarmingly, expansive. Not only did the wily, persuasive man of advice slither his way into the confidence of the governing classes, he invited the easy betrayal of secrets. He was not only a conduit for young flesh and pleasures, but for classified information.

Being the Prince of Darkness, Mandelson has always managed some form of reputational reincarnation. This time, a stake has been taken to him. Let us hope it stays there, lodged for posterity. As for the party he represents, and the daft Prime Minister who made him ambassador to Washington, the die may well have been cast. What the Profumo affair did for the Macmillan government in the early 1960s Mandelson risks doing to Starmer’s in 2026.

By AFP

February 10, 2026

In an Instagram post, Roan said that "no artist, agent or employee should be expected to defend or overlook actions that conflict so deeply with our own moral values" - Copyright GETTY IMAGES NORTH AMERICA/AFP Amy Sussman

US singer-songwriter Chappell Roan announced on Monday that she had left her talent agency, after its CEO was named in files related to late convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.

The Epstein Files Transparency Act (EFTA), passed overwhelmingly by Congress in November, compelled the Department of Justice (DOJ) to release all of the documents in its possession related to the disgraced financier.

Roan, 27, had been represented by “Wasserman,” an agency that boasts a number of high-profile clients, including Adam Sandler and Brad Pitt, and is led by Casey Wasserman, who is also the chairman of the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics.

In an Instagram post on Monday, Roan said that “no artist, agent or employee should be expected to defend or overlook actions that conflict so deeply with our own moral values.”

“I have deep respect and appreciation for the agents and staff who work tirelessly for their artists and I refuse to stand by,” she added.

The Grammy winner noted that “artists deserve representation that aligns with their values” and the decision “reflects my belief that meaningful change in our industry requires accountability and leadership that earns trust.”

Roan made no mention of Epstein himself or the Epstein files in the statement announcing her departure from the talent agency.

Wasserman in a statement last month acknowledged what appeared to be a series of flirty and sexually suggestive emails he exchanged in 2003 with Ghislaine Maxwell.

Maxwell was sentenced to two decades in prison in 2022 for her role in a scheme to sexually exploit and abuse multiple minor girls with Epstein.

Wasserman, 51, who was married at the time of his flirtations with Maxwell, has not been accused of any wrongdoing in the Epstein scandal, which has dogged US President Donald Trump’s administration.

Trump moved in the same social circles as the disgraced financier and his right-wing base has long been obsessed with the belief that Epstein oversaw a sex trafficking ring for the world’s elite.

2 Comments

This Chomsky scandal isn’t just exposing his flaws, but the distasteful eagerness of leftists willing to assume the absolute worst of someone they supposedly admired.

Chomsky was hurting and Epstein helped and he didn’t want to look too deeply at his friend’s background. This isn’t a flaw limited to elitists. If you have ever had a friend or family member who was accused of something bad you might know the temptation to think it can’t be true. Why anyone would think this is just an elitist failing escapes me. It isn’t. People could say Chomsky should be ashamed of his actions but many seem to want to go much further and treat him as a monster.

It could be that playing the role of public moralist is itself corrupting. Chomsky should have noticed the beam in his own eye and his leftist critics might ask themselves why they feel the need to demonize him.

Chris Hedges has a different view:

“. . . [Valeria Chomsky’s] letter regurgitates the formula of everyone outed in the Epstein files. I know and have long admired Noam. He is, arguably, our greatest and most principled intellectual. I can assure you he is not as passive or gullible as his wife claims. He knew about Epstein’s abuse of children. They all knew. And like others in the Epstein orbit, he did not care. . . . Noam, of all people, knows the predatory nature of the ruling class and the cruelty of capitalists, where the vulnerable, especially girls and women, are commodified as objects to be used and exploited. He was not fooled by Epstein. He was seduced. . . . The ruling class offers nothing without expecting something in return. The closer you get to these vampires the more you become enslaved. Our role is not to socialize with them. It is to destroy them.”