U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Scott Turner leads a prayer as U.S. President Donald Trump hosts his first cabinet meeting with Elon Musk in attendance, in Washington, D.C., U.S., February 26, 2025. REUTERS/Brian Snyder

Sarah K. Burris

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau was founded after the Wall Street Crisis and mortgage collapse that happened in 2007 and 2008, with the specific purpose of having a government agency that would regulate the financial industry for customers, not prioritize profits. But the top conversation wasn't the affordability crisis. It was prayer.

The president now welcomed prayers at the start of every government meeting. Federal employees are also encouraged to spend an hour each week in prayer while at work, CNN reported Sunday.

While Trump may not be focused on it, his allies are plotting to remake America in the image of a kind of Christian version of Sharia Law.

"By this summer, the group — Trump’s Religious Liberty Commission — is expected to produce a blueprint for policy changes that could redefine the boundaries between government and religion in American life," wrote CNN.

Trump told the commission that they must bring religion back to America. The group is focusing on ways to sue state and local governments that they say block "religious freedom." They'll try to block public funding of K-12 schools, they say, that are hostile to faith.

They're also watching for ways to bring cases before the Supreme Court that could give them an opportunity to remake the First Amendment's Establishment Clause, which bars the government from endorsing a national religion.

“We are in a religious and cultural war right now, and every single one of us is a combatant,” said TV "psychologist" Dr. Phil McGraw during a September meeting. “Nobody can afford to sit on the sidelines.”

The White House continues to berate devout Catholic President Joe Biden, claiming that he "weaponized" the federal government against the church.

While the Trump commission has some Jewish and Muslim leaders on it, the panel is dominated by far-right Christianity.

It wasn't until last week that the commission broke into the popular zeitgeist, when commissioner and "former beauty pageant contestant Carrie Prejean Boller, challenged Jewish speakers about their beliefs and Israel’s war against Hamas."

She's one of many on the commission eager to talk about the "satanic" forces coming from other religions they deem incorrect.

The commission, housed in the Justice Department, issues only nonbinding recommendations, but its influence is already evident. The Education Department recently warned schools they could lose funding if they block students or staff from praying, mirroring a proposal floated at a commission hearing, and the Pentagon moved to reinstate faith into the U.S. military after commissioners pushed for more power for chaplains and a return of prayer.

Commission member Kelly Shackelford claimed the group is finding “problems” with religious freedom across schools, government, the private sector, health care, and the military.

It's all part of a wider Trump‑era shift to faith‑based units across federal agencies that have been repurposed from mainly coordinating with religious charities to actively promoting far-right Christianity.

U.S. President Donald Trump in Clive, Iowa, January 27, 2026. REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque

A conservative Catholic was expelled from President Donald Trump’s so-called Religious Liberty Commission this week over remarks at a hearing on antisemitism in which she pushed back against those who conflate criticism of Israel and its genocidal war on Gaza with hatred of Jewish people.

Religious Liberty Commission Chair Dan Patrick, who is also Texas’ Republican lieutenant governor, announced Wednesday that Carrie Prejean Boller had been ousted from the panel, writing on X that “no member... has the right to hijack a hearing for their own personal and political agenda on any issue.”

“This is clearly, without question, what happened Monday in our hearing on antisemitism in America,” he claimed. “This was my decision.”

Patrick added that Trump “respects all faiths”—even though at least 13 of the commission’s remaining 15 members are Christian, only one is Jewish, and none are Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, or other religions to which millions of Americans adhere. A coalition of faith groups this week filed a federal lawsuit over what one critic described as the commission’s rejection of “our nation’s religious diversity and prioritizing one narrow set of conservative ‘Judeo-Christian’ beliefs.”

Noting that Israeli forces have killed “tens of thousands of civilians in Gaza,” Prejean Boller asked panel participant and University of California Los Angeles law student Yitzchok Frankel, who is Jewish, “In a country built on religious liberty and the First Amendment, do you believe someone can stand firmly against antisemitism... and at the same time, condemn the mass killing of Palestinians in Gaza, or reject political Zionism, or not support the political state of Israel?”

“Or do you believe that speaking out about what many Americans view as genocide in Gaza should be treated as antisemitic?” added Prejean Boller, who also took aim at the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) Working Definition of Antisemitism, which has been widely condemned for conflating criticism of Israel with anti-Jewish bigotry.

Frankel replied “yes” to the assertion that anti-Zionism is antisemitic.

Prejean Boller also came under fire for wearing pins of US and Palestinian flags during Monday’s hearing.

“I wore an American flag pin next to a Palestinian flag as a moral statement of solidarity with civilians who are being bombed, displaced, and deliberately starved in Gaza,” Prejean Boller said Tuesday on X in response to calls for her resignation from the commission.

“I did this after watching many participants ignore, minimize, or outright deny what is plainly visible: a campaign of mass killing and starvation of a trapped population,” she continued. “Silence in the face of that is not religious liberty, it is moral complicity. My Christian faith calls on me to stand for those who are suffering [and] in need.”

“Forcing people to affirm Zionism as a condition of participation is not only wrong, it is directly contrary to religious freedom, especially on a body created to protect conscience,” Prejean Boller stressed. “As a Catholic, I have both a constitutional right and a God-given freedom of religion and conscience not to endorse a political ideology or a government that is carrying out mass civilian killing and starvation.”

Zionism is the movement for a homeland for the Jewish people in Palestine—their ancestral birthplace—under the belief that God gave them the land. It has also been criticized as a settler-colonial and racist ideology, as in order to secure a Jewish homeland, Zionists have engaged in ethnic cleansing, occupation, invasions, and genocide against Palestinian Arabs.

Prejean Boller was Miss California in 2009 and Miss USA runner-up that same year. She launched her career as a Christian activist during the latter pageant after she answered a question about same-sex marriage by saying she opposed it. Then-businessman Trump owned most of Miss USA at the time and publicly supported Prejean Boller, saying “it wasn’t a bad answer.”

Since then, Prejean Boller has been known for her anti-LGBTQ+ statements and for paying parents and children for going without masks during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Council on American Islamic Relations (CAIR) commended Prejean Boller Wednesday “for using her position to oppose conflating criticism of Israel with antisemitism and encourage solidarity between Muslims, Christians, and Jews,” calling her “one of a growing number of Americans, including political conservatives, who recognize that corrupted politicians have been trying to silence and smear Americans critical of the Israeli government under the guise of countering antisemitism.”

“We also condemn Texas Lt. Gov. Patrick’s baseless and predictable decision to remove her from the commission for refusing to conflate antisemitism with criticism of the Israel apartheid government,” CAIR added.

In her statement Tuesday, Prejean Boller said, “I will not be bullied.”

“I have the religious freedom to refuse support for a government that is bombing civilians and starving families in Gaza, and that does not make me an antisemite,” she insisted. “It makes me a pro-life Catholic and a free American who will not surrender religious liberty to political pressure.”

“Zionist supremacy has no place on an American religious liberty commission,” Prejean Boller added.

President Donald Trump prays during a group prayer during the National Prayer Breakfast in Washington, D.C., February 5, 2026. REUTERS/Al Drago

Thomas Kika

Donald Trump's forceful and brutish handling of his foreign and domestic policies saw him likened to a "pagan king" in a new analysis in The New York Times, with documentary filmmaker Leighton Woodhouse arguing that he has abandoned the true ideals at the heart of "Christian values."

In a piece for the Times published Wednesday, Woodhouse took inspiration from Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney's comments about Trump's leadership style, which he summed up as, "the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must." Woodhouse delved extensively into the philosophies of ancient, pre-Christian societies, which he argued more closely resemble the operating philosophy of Trump's second presidency.

Trump, Woodhouse wrote, operates as is if "the weak and the vanquished" have no "inherent moral value at all," meaning that the U.S. can do whatever it likes, so long as it has the power to do so. He also cited comments last month from Trump's controversial adviser, Stephen Miller, in which he justified the president's desire to take Greenland by arguing that the world is "governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power," and that the U.S. can not be bound by "international niceties" if it has the power to do something it wants.

All of that flies in the face of the core principles of Christianity, which Trump and many others in his administration have claimed to fight for. The true values of the religion, Woodhouse explained, are based on the notion that even the weak have inherent worth, and that assaults on them are an affront to God. In this way, he concluded, Trump's conduct puts him more in line with Ancient Greek or pre-Christian Roman rulers.

"By brazenly jacking Venezuela for its oil and threatening to acquire Greenland against its will, the U.S. is acting as the ancient Greeks, the ancient Persians and the Germanic tribes conducted themselves: brutishly, without shame or apology," Woodhouse wrote.

He continued: "And the abdication of Christian values is already shaping the conduct of our government toward its citizens, as in Minneapolis, where immigration agents have killed two protesters. The Trump administration appears unconstrained not only by the limits imposed by the Constitution but by the standards of an average American’s conscience. Federal agents’ treatment of both immigrants and U.S. citizens in Minneapolis is the reflection of a government that has abandoned the moral instinct that it is wrong for the powerful to abuse the weak."

Similar analysis also recently came from The Bulwark's Andrew Egger, who wrote that Trump seems to view himself "as Christianity’s Punisher," someone willing to do the "dirty work" of committing violence to protect the faith. This, Egger argued, runs directly against the religion's core values.

"This is part of what makes Trump-brand Christianity as a cultural and political force so dangerous," Egger concluded. "Trump’s political project is seen by the MAGA faithful as utterly righteous, the work of God on earth against the forces of Satan. But he has broad license to transgress all moral boundaries as he does that work... None of this, it should probably go without saying, is compatible in the slightest with the teachings of actual Christianity. Sin is sin, the faith teaches, no matter whom it’s directed against..."

Evangelical Pastor Paula White with U.S. President Donald Trump in the White House (Official White House Photo by Joyce N. Boghosia/Flickr)

A recent meeting of President Donald Trump's Religious Liberty Commission rapidly devolved into a shouting match between commission members over the issue of antisemitism.

That's according to a Tuesday article by MS NOW's Ja'han Jones, who wrote that several conservative Christian members of the commission got into a "fit of infighting" when discussing antisemitism on college campuses. Commission members Carrie Prejean Boller (who was Miss California U.S.A. in 2009) and Seth Dillon — who is the CEO of conservative satire site The Babylon Bee — battled over far-right commentator Tucker Carlson and whether MAGA influencer Candace Owens is antisemitic.

"I have not heard one thing out of her mouth that I would say is antisemitic," Boller said of Owens, despite Owens being named "Antisemite of the Year" in 2024 by advocacy group StopAntisemitism.

Boller also argued loudly with several Jewish commission members over the difference between antisemitism and anti-Zionism, the latter of which is typically defined by support for the modern state of Israel (though it is also seen as a coded attack on Jewish people). Boller, who is Catholic, proclaimed "Catholics do not embrace Zionism," and garnered boos from the crowd when condemning Islamophobia.

Now, Boller is facing calls from within the MAGA world to either resign for the commission, or for her to be removed if she refused to step down. This includes far-right commentator Laura Loomer (known as Trump's informal "loyalty enforcer") who called Boller's comments "disgraceful."

"The Trump administration should not reward individuals who openly spread anti-Jewish propaganda," Loomer tweeted.

Trump convened the Religious Liberty Commission last year, whose members include Texas Lieutenant Gov. Dan Patrick (R) and Dr. Phil McGraw, as well as former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson, Rev. Franklin Graham, Pastor Paula White and Cardinal Timothy Dolan, among others. Their commission itself is set to disband on July 4 of this year, unless Trump chooses to extend it. Jones wrote that given the outburst at its latest meeting, the commission may likely sunset this summer.

"That MAGA world is engaged in this kind of circular firing squad over antisemitism is no surprise and, one might argue, the natural outcome for a political movement fueled by bigotry of varying sorts," Jones wrote.

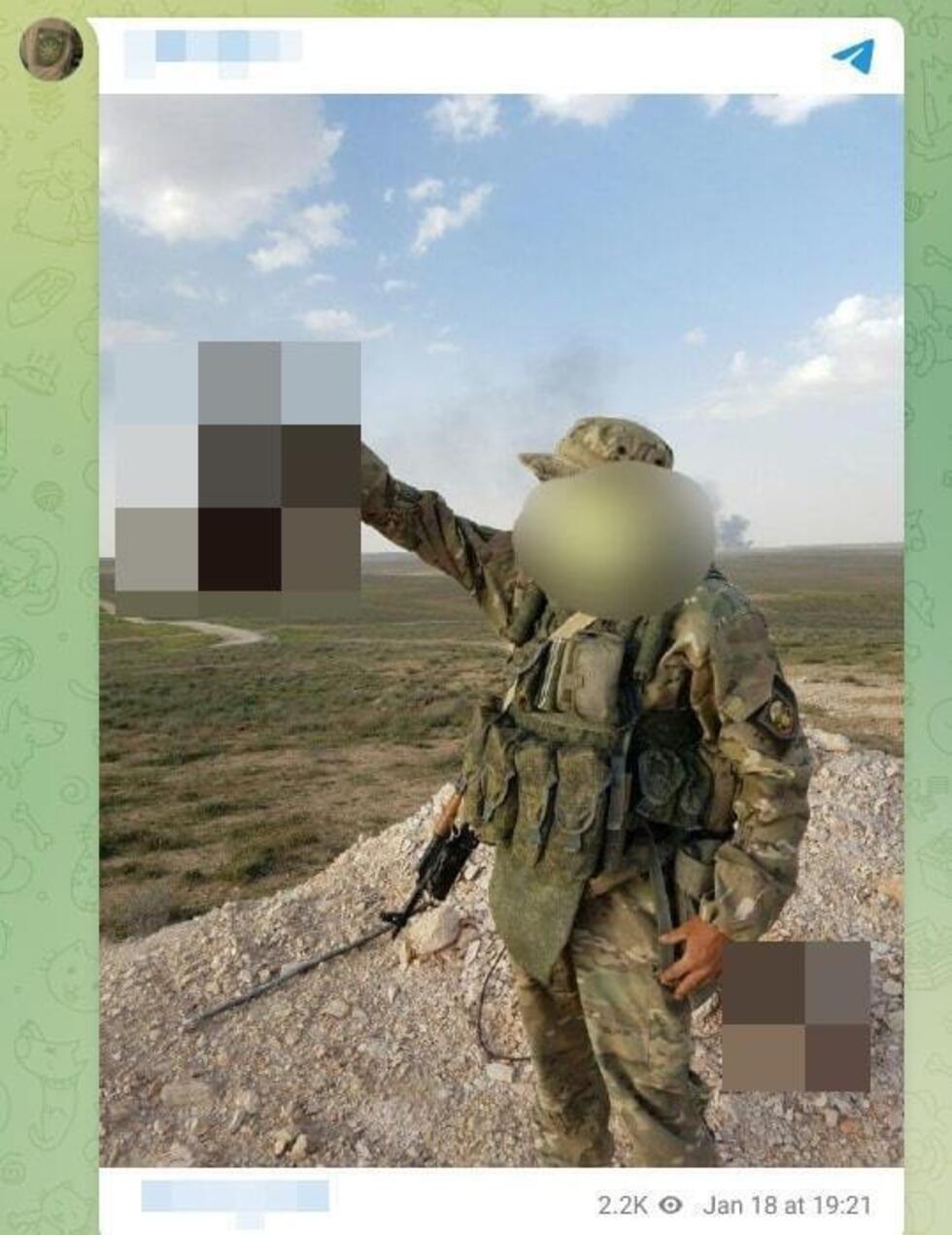

Videos posted on social media by the Rusich paramilitary group feature pagan rituals, heavy machine guns and Nazi salutes and promote violence and supremacist ideology. © Telegram / dshrg2 - Molfar.Institute

Videos posted on social media by the Rusich paramilitary group feature pagan rituals, heavy machine guns and Nazi salutes and promote violence and supremacist ideology. © Telegram / dshrg2 - Molfar.Institute

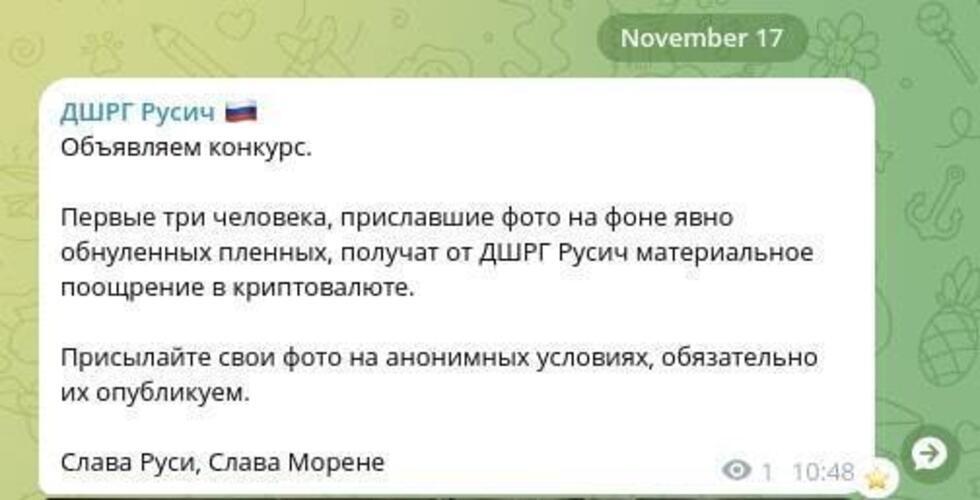

This message was posted on Rusich Telegram channel on November 15. It calls on followers to send images of Ukrainian soldiers who have been executed in exchange for payment. © Telegram / dshrg2

This message was posted on Rusich Telegram channel on November 15. It calls on followers to send images of Ukrainian soldiers who have been executed in exchange for payment. © Telegram / dshrg2