It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Sunday, September 20, 2020

Published September 19, 2020 By Bob Brigham

With polls showing President Donald Trump trailing former Vice President Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential campaign, the incumbent appears nervous that he might lose a fair vote.

At a campaign rally in Fayetteville, North Carolina on Saturday, Trump spoke for over 90 minutes.

In addition to vowing he will “fill” the Supreme Court vacancy created by the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and accusations that Biden has performance-enhancing drugs injected in his ass, Trump threatened to call off the election by banning Biden from running.

“You can’t have this guy as your president,” Trump argued.

“You can’t have — maybe I’ll sign an executive order, you cannot have him as your president,” Trump argued as his supporters cheered.

Trump: Maybe I’ll sign an executive order, you can’t have him as your president pic.twitter.com/et3Y956a88

— Acyn Torabi (@Acyn) September 20, 2020

Social distancing and mask wearing is extremely common in the United States. But younger people, white people, men, and those with lower incomes are less likely than their counterparts to engage in measures that mitigate the spread of the novel coronavirus known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), according to new research published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

“In a situation like the current pandemic, where you have no vaccine and the virus is spreading quickly, the health behaviors of the public become your greatest asset in both controlling the spread of COVID-19 and protecting the public’s health,” said study author Fares Qeadan, an assistant professor of biostatistics at the University of Utah.

“The starting point for using this asset effectively is in knowing who is undertaking what protective health behaviors and how those behaviors intersect with perceptions of COVID-19 as a threat or not a threat.”

For their study, the researchers examined data from 25,269 American adults who participated in the COVID Impact Survey, a weekly survey conducted by the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago. The data was collected in April, May, and June of 2020.

“Our study found that the median number of protective measures taken by Americans is 9 (+-2) out of a list of 19 measures,” Qeadan told PsyPost, indicating a moderate level of compliance with measures to prevent the spread of the virus.

Nearly 95% of participants reported washing or sanitizing their hands, 90.11% reported staying six feet away from others, and 86.18% reported wearing a mask or face covering. About 40% of the participants reported working from home.

The researchers also found that demographic and socioeconomic variables were associated with differing rates of protective COVID-19 measures. “Specifically, the study reveals that individuals with higher incomes, insurance, higher education levels, large household size, age 60+, females, minorities, those who have asthma, have hypertension, are overweight or obese, and those who suffer from mental health issues during the pandemic were significantly more likely to report taking precautionary protective measures relative to their counterparts,” Qeadan told PsyPost.

“Further, this study shows that individuals with a known relationship to COVID-19 (positive for COVID-19, knowing an individual with COVID-19, or knowing someone who had died from COVID-19) are strongly engaged with the protective health measures of washing hands, avoiding public places, and canceling social engagements.”

“However, those with a COVID-19 diagnosis had stronger emphasis on self-isolation (cancelling social events, avoiding large crowds, staying home, and stockpiling food and water), whereas those living with someone with COVID-19 or having a close friend or family member dying from COVID-19 had stronger emphasis on personal protective health measures (washing/sanitizing hands, wearing a face mask, and six-feet distancing),” Qeadan explained.

“The takeaway message is to increase the number of protective measures one takes to fight this pandemic. I hope that people are seeking out evidence-based information during this pandemic and taking it seriously. Anyone who reads about our research can probably see themselves and people they know in the health behaviors we studied.”

“Our article, as well as others, provides readers an opportunity to reflect on if they are being safe enough and who they know that might need some encouragement in being a little safer. Hopefully, we have helped illuminate the relationships between health behaviors, some sociodemographic factors, and people’s lived experience with the virus,” Qeadan said.

“Follow-up studies would be helpful in understanding how behaviors and perceptions are changing over time; as numbers fall and rise are behaviors and perceptions changing accordingly or do people get fatigued over time and start to be less adherent to these protective measures?” Qeadan said.

“There is still work to do, but our data can be useful in targeting certain people who aren’t taking the virus as seriously as they should and it provides insight into how public information might be better targeted in future pandemics. It would be essential to conduct larger population-based studies that include areas where individuals are not able to access the internet.”

The study, “What Protective Health Measures Are Americans Taking in Response to COVID-19? Results from the COVID Impact Survey“, was authored by Fares Qeadan, Nana Akofua Mensah, Benjamin Tingey, Rona Bern, Tracy Rees, Sharon Talboys, Tejinder Pal Singh, Steven Lacey, and Kimberley Shoaf.

Police, protesters clash as London eyes tighter virus rules

Protesters take part in a "Resist and Act for Freedom" protest against a mandatory coronavirus vaccine, wearing masks, social distancing and a second lockdown, in Trafalgar Square, London, Saturday, Sept. 19, 2020. (Yui Mok/PA via AP)

Scuffles broke out as police moved in to disperse hundreds of demonstrators who gathered in London’s central Trafalgar Square. Some protesters formed blockades to stop officers from making arrests and traffic was brought to a halt in the busy area.

The “Resist and Act for Freedom” rally saw dozens of people holding banners and placards such as one reading “This is now Tyranny” and chanting “Freedom!” Police said there were “pockets of hostility and outbreaks of violence towards officers.”

Britain’s Conservative government this week imposed a ban on all social gatherings of more than six people in a bid to tackle a steep rise in COVID-19 cases in the country. Stricter localized restrictions have also been introduced in large parts of England’s northwestern cities, affecting some 13.5 million people.

London Mayor Sadiq Khan said the city may impose some of the measures already in place elsewhere in the U.K. That may include curfews, earlier closing hours for pubs and banning household visits.

“I am extremely concerned by the latest evidence I’ve seen today from public health experts about the accelerating speed at which COVID-19 is now spreading here in London,” Khan said Friday. “It is increasingly likely that, in London, additional measures will soon be required to slow the spread of the virus.”

The comments came as new daily coronavirus cases for Britain rose to 4,322, the highest since early May.

The latest official estimates released Friday also show that new infections and hospital admissions are doubling every seven to eight days in the U.K. A survey of randomly selected people — not including those in hospitals or nursing homes — estimated that almost 60,000 people in England had COVID-19 in the week of Sept.4, about 1 in 900 people.

Britain has Europe’s worst death toll in the pandemic with 41,821 confirmed virus-related deaths, but experts say all numbers undercount the true impact of the pandemic.

In a statement, British police said the protesters Saturday were “putting themselves and others at risk” and urged all those at the London rally to disperse immediately or risk arrest.

___

Follow AP’s pandemic coverage at http://apnews.com/VirusOutbreak and https://apnews.com/UnderstandingtheOutbreak

Underwater and on fire: US climate change magnifies extremes

America’s worsening climate change problem is as polarized as its politics. Some parts of the country have been burning this month while others were underwater in extreme weather disasters.

The already parched West is getting drier and suffering deadly wildfires because of it, while the much wetter East keeps getting drenched in mega-rainfall events, some hurricane related and others not. Climate change is magnifying both extremes, but it may not be the only factor, several scientists told The Associated Press.

“The story in the West is really going to be ... these hot dry summers getting worse and the fire compounded by decreasing precipitation,” said Columbia University climate scientist Richard Seager. “But in the eastern part more of the climate change impact story is going to be more intense precipitation. We see it in Sally.”

North Carolina State climatologist Kathie Dello, a former deputy state climatologist in Oregon, this week was talking with friends abut the massive Oregon fires while she was huddled under a tent, dodging 4 inches (10 centimeters) of rain falling on the North Carolina mountains.

“The things I worry about are completely different now,” Dello said. “We know the West has had fires and droughts. It’s hot and dry. We know the East has had hurricanes and it’s typically more wet. But we’re amping up both of those.”

In the federal government’s 2017 National Climate Assessment, scientists wrote a special chapter warning of surprises due to global warming from burning of coal, oil and natural gas. And one of the first ones mentioned was “compound extreme events.”

“We certainly are getting extremes at the same time with climate change,” said University of Illinois climate scientist Donald Wuebbles, one of the main authors.

Since 1980, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has tracked billion-dollar disasters, adjusting for inflation, with four happening in August including the western wildfires. NOAA applied meteorologist Adam Smith said that this year, with at least 14 already, has a high likelihood of being a record.

Fifteen of the 22 billion-dollar droughts in the past 30 years hit states west of the Rockies, while 23 of the 28 billion-dollar non-hurricane flooding events were to the east.

For more than a century scientists have looked at a divide — at the 100th meridian — that splits the country with dry and brown conditions to the west and wet and green ones to the east

Seager found that the wet-dry line has moved about 140 miles (225 kilometers) east — from western Kansas to eastern Kansas — since 1980.

And it’s getting more extreme.

Nearly three-quarters of the West is now in drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. Scientists say the West is in about the 20th year of what they call a “megadrought,” the only one since Europeans came to North America.

Meager summer rains are down 26% in the last 30 years west of the Rockies. California’s anemic summer rain has dropped 41% in the past 30 years. In the past three years, California hasn’t received more than a third of an inch (0.8 centimeters) of rain in June, July and August, according to NOAA records.

California also is suffering its worst fire year on record, with more than 5,300 square miles (13,760 square kilometers) burned. That’s more than double the area of the previous record set in 2018. People have been fleeing unprecedented and deadly fires in Oregon and Washington with Colorado also burning this month.

“Climate change is a major factor behind the increase in western U.S. wildfires,” said A. Park Williams, a Columbia University scientist who studies fires and climate.

“Since the early 1970s, California’s annual wildfire extent increased fivefold, punctuated by extremely large and destructive wildfires in 2017 and 2018,” a 2019 study headed by Williams said, attributing it mostly to “drying of fuels promoted by human‐induced warming.”

During the western wildfires, more than a foot rain fell on Alabama and Florida as Hurricane Sally parked on the Gulf Coast, dropping as much as 30 inches (76 centimeters) of rain at Orange Beach, Alabama. Studies say hurricanes are slowing down, allowing them to deposit more rain.

The week before Sally hit, a non-tropical storm dumped half a foot of rain on a Washington, D.C., suburb in just a few hours. Bigger downpours are becoming more common in the East, where the summer has gotten 16% wetter in the last 30 years.

In August 2016, a non-tropical storm dumped 31 inches (nearly 79 centimeters) of rain in parts of Louisiana, killing dozens of people and causing nearly $11 billion in damage. Louisiana and Texas had up to 20 inches (51 centimeters) of rain in March of 2016. In June 2016, torrential rain caused a $1 billion in flood damage in West Virginia.

In the 1950s, areas east of the Rockies averaged 87 downpours of five inches or more a year. In the 2010s, that had soared to 149 a year, according to data from NOAA research meteorologist Ken Kunkel.

It’s simple physics. With each degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) that the air warms, it holds 7% more moisture that can come down as rain. The East has warmed that much since 1985, according to NOAA.

While climate change is a factor, Seager and Williams said what’s happening is more extreme than climate models predict and there must be other, possibly natural weather phenomenon also at work.

Pennsylvania State University climate scientist Michael Mann said that La Nina — a temporary natural cooling of parts of the equatorial Pacific that changes weather worldwide — is partly responsible for some of the drought and hurricane issues this summer. But that’s on top of climate change, so together they make for “dual disasters playing out in the U.S.,” Mann said.

As for where you can go to escape climate disasters, Dello said, “I don’t know where you can go to outrun climate change anymore.”

“I’m thinking Vermont,” she said, then added Vermont had bad floods from 2011’s Hurricane Irene.

___

Read stories on climate issues by The Associated Press at https://apnews.com/hub/climate.

___

Follow Seth Borenstein on Twitter at @borenbears.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

The corporate support for a QAnon-promoting politician is another example of how the conspiracy theory has penetrated mainstream politics, spreading beyond its origins on internet message boards popular with right-wing extremists.

Dozens of QAnon-promoting candidates have run for federal or state offices during this election cycle. Collectively, they have raised millions of dollars from thousands of donors. Individually, however, most of them have run poorly financed campaigns with little or no corporate or party backing. Unlike state Rep. Susan Lynn, who chairs the Tennessee House finance committee, few are incumbents who can attract corporate PAC money.

Though she repeatedly posted a well-known QAnon slogan on her Twitter and Facebook accounts, Lynn told the AP in an interview Friday that she does not support the conspiracy theory.

Walmart did not respond to repeated requests for comment made by email and through its website. An Amazon spokeswoman declined to comment. A spokeswoman for another donor to Lynn’s campaign, Kentucky-based distillery company Brown-Forman, which has a facility in Tennessee, said the company didn’t know about Lynn’s QAnon posts and wouldn’t have donated to her campaign through its Jack Daniel’s PAC if it had.

“Now that our awareness is raised, we will reevaluate our criteria for giving to help identify affiliations like this in the future,” Elizabeth Conway said in a statement.

Corporate PAC managers typically decide which candidates to support on the basis of narrow, pragmatic policy issues rather than broader political concerns, said Anthony Corrado, a Colby College government professor and campaign finance expert.

“In many instances, you don’t have any kind of corporate board oversight or any kind of accountability in terms of review of contributions before they’re made,” Corrado said. “Some corporations now have adopted policies about the supervision of PAC contributions because of the reputational risks involved in this.”

At least 81 current or former congressional candidates have supported the conspiracy theory or promoted QAnon content, with at least 24 qualifying for November’s general election ballot, according to the liberal watchdog Media Matters for America.

\

As of Friday, the candidates collectively had raised nearly $5 million in contributions for this election cycle, but only eight had raised over $100,000 individually, according to the AP’s review of Federal Election Commission data. The FEC’s online database doesn’t have any fundraising reports for 30 of the candidates, the vast majority of whom are running as Republicans.

Congress is virtually certain to have at least one QAnon-supporting member next year. Marjorie Taylor Greene, whose campaign has raised over $1 million, appeared to be coasting to victory in a deep-red congressional district in Georgia even before her Democratic opponent dropped out of the race.

At the state level, the AP and Media Matters have identified more than two dozen legislative candidates who have expressed some support or interest in QAnon.

QAnon centers on the baseless belief that President Donald Trump is waging a secret campaign against enemies in the “deep state” and a child sex trafficking ring run by satanic pedophiles and cannibals. Trump has praised QAnon supporters and often retweets accounts that promote the conspiracy theory.

QAnon has been linked to killings, attempted kidnappings and other crimes. In May 2019, an FBI bulletin mentioning QAnon warned that conspiracy theory-driven extremists have become a domestic terrorism threat.

Lynn said her social media posts do not indicate any support for the conspiracy theory.

“This is the United States of America, and I am absolutely free to tweet or retweet anything I want,” she said. “I don’t understand why this is even an issue. Believe me, I am not in the inside of some QAnon movement.”

But in October 2019, Lynn retweeted posts by QAnon-promoting accounts with tens of thousands of followers. One of the posts she retweeted praised Trump and included the hashtag #TheGreatAwakening, a phrase commonly invoked by QAnon followers.

Between Oct. 31, 2019, and Jan. 9, 2020, her campaign received $4,750 in donations from Amazon.com Services LLC, BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee’s PAC, health insurer Humana, the Southwest Airlines Co. Freedom Fund and Walmart Inc.

“Like many other companies, our PAC periodically contributes to elected officials in Tennessee, including those serving in leadership like Rep. Lynn,” BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee spokeswoman Dalya Qualls said in a statement.

In April, Lynn updated her Facebook page with a cover photo that included a flag with stars forming a “Q” above the abbreviation “WWG1WGA,” which stands for the QAnon slogan “Where we go one, we go all.” In May and June, Lynn punctuated several tweets with the same abbreviation.

And when a leading QAnon supporter nicknamed “Praying Medic” tweeted the message, “Is it time to Q the Trump rallies?” Lynn responded, “It is time!” in a May 31 tweet of her own.

Lynn said she viewed “Where we go one, we go all” as a “very unifying slogan” and didn’t know it was a QAnon motto. However, a handful of Facebook users who replied to her updated cover photo in April commented on the QAnon connection. The flag is no longer her cover photo but could still be seen in the feed on her page on Friday.

In July, AT&T Tennessee PAC, Cigna Corporation PAC and Jack Daniel’s PAC contributed a total of $4,000 to Lynn’s campaign.

The PACs linked to BlueCross BlueShield, AT&T Tennessee, Cigna, Southwest Airlines and Jack Daniel’s had also previously donated to Lynn’s campaign before she amplified QAnon-promoting Twitter accounts last year.

AP contacted all of the companies mentioned in this story. Some did not respond to requests for comment and others declined to comment.

___

Associated Press data journalist Andrew Milligan in New Haven, Connecticut; and Adrian Sainz in Memphis, Tennessee, contributed to this report.

Ginsburg was also a reliable vote over the decades in favor of environmental protections.

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court Ruth Bader Ginsburg takes her seat as she arrives to address first-year law students at the Georgetown Law Center in Washington, DC on Sept. 20, 2017. | Nicholas Kamm/AFP/Getty Images

By ALEX GUILLÉN

09/19/2020

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who died Friday at age 87, helped establish critical Supreme Court precedent that empowered EPA to address the greenhouse gas emissions driving climate change.

The landmark ruling she joined in 2007 that affirmed EPA’s power set up the Obama administration to issue rules limiting carbon pollution from cars, power plants and other sources — and set up a contentious legal battle over the extent of federal authority still being waged today.

Though the core of her legacy centered on women’s rights and gender equality, Ginsburg was also a reliable vote over the decades in favor of environmental protections, and activists mourned her loss late Friday.

“Through her expansive mind, sound temperament and unwavering judicial integrity, she plied the Constitution as a living instrument of American life, lending it meaning in the life of us all,” said Gina McCarthy, president of the Natural Resources Defense Council and former EPA administrator.

"Our communities are safer, healthier and more free because of RBG," said League of Conservation Voters President Gene Karpinski.

Ginsburg was clearly aware of the threats posed by climate change. At an event in December, she cited Swedish teen climate activist Greta Thunberg as one of the future leaders giving her hope, according to Vanity Fair.

“The young people that I see are fired up, and they want our country to be what it should be,” she said. “One of the things that makes me an optimist are the young people.”

Ginsburg was part of the five-justice majority in the high court's first-ever ruling on climate change, 2007’s Massachusetts v. EPA, that said the Clean Air Act gave EPA the authority — and, effectively, a mandate — to regulate greenhouse gases from automobile tailpipes.

That ruling led directly to the Obama administration in 2009 beginning to regulate carbon dioxide emitted from cars and trucks for the first time at the federal level.

Then in 2011, Ginsburg authored another ruling, American Electric Power v. Connecticut, that reiterated EPA’s authority to target greenhouse gases — this time for a unanimous court.

Technically, Ginsburg ruled against several states that wanted to sue private power companies under public nuisance laws to set a cap on their carbon dioxide emissions. The prior 2007 ruling meant EPA’s authority blocked the states’ federal common law claims, Ginsburg wrote.

But environmentalists and Democrats saw a bright silver lining — confirmation that the federal government can and should be acting on climate change already.

The Obama administration subsequently moved to issue rules for power plants, at the time the nation’s top source of greenhouse gases, after Congress failed to pass a cap-and-trade bill.

The regulatory and legal fighting over those power plant rules and their Trump administration replacements has meant power plants have not yet actually been subject to carbon dioxide regulation. But the specter of federal rules — along with market pressure from cheap natural gas and renewables — helped cause a huge shift in the nation's electricity mix: The U.S. is projected to generate just 20 percent of its electricity from coal this year, compared with almost half when the court ruled.

Coincidentally, Ginsburg’s ruling could play a key role in an upcoming legal battle over climate change compensations.

More than a dozen cities, counties and states in recent months have sued fossil fuel companies in state courts in a wave of lawsuits intended to make the corporations pay for climate change-related harms such as extreme weather and sea level rise. The companies have tried to move those cases out of the states and into federal courts — where they probably would be blocked as Connecticut’s suit was in 2011. But three appellate courts that have weighed in on the jurisdictional question have sent the cases back to the state courts, which could open the companies up to untold liability.

When the Supreme Court returns for its fall term in a few weeks, the eight remaining justices are slated to decide whether to wade into the jurisdictional fight in these climate change suits. If the justices allow them to continue in state courts, a fresh wave of litigation could soon hit greenhouse gas emitters.

While Ginsburg was a key voice in defining the Supreme Court’s short history on climate law, she also has a long record of voting for other types of environmental protection.

In 2001, she joined a unanimous court in ruling that EPA cannot consider implementation costs when deciding on national air quality limits for smog, soot and other major pollutants. It is considered one of the high court’s most important environmental rulings, and those EPA regulations are credited with saving and improving millions of lives.

Six years ago, Ginsburg led a 6-2 majority that reversed a lower court and upheld an Obama rule limiting air pollution that floats across state lines, saving a regulation credited with helping shut down some of the nation's dirtiest power plants.

And in April, she was part of a six-justice majority that said pollution that travels into waterways via groundwater can be subject to the Clean Water Act. While the high court's new standard was narrower than environmentalists had hoped, it nonetheless opens up companies to new potential liabilities.

Indeed, Ginsburg was a consistent vote in favor of broad Clean Water Act jurisdiction as questions about the reach of the 1972 law became a legal quagmire over the past two decades. Those questions are widely expected to reach the high court again in the coming years.

She joined with the court’s liberals in the dissent in Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. United States in 2001, in which the majority ruled that isolated ponds and wetlands are out of federal reach. In the 2006 case Rapanos v. United States, which resulted in a splintered 4-1-4 decision, Ginsburg joined an opinion by then-justice John Paul Stevens that argued for sweeping federal jurisdiction over virtually any water feature.

The Trump administration earlier this year finalized a regulation enshrining a narrow definition of federally protected waterways that legal experts say is on questionable ground, given that it is primarily based on then-Justice Antonin Scalia’s plurality opinion in the 2006 case, which garnered the backing of only four of the justices. Challenges to the Trump administration’s rule have been filed by Democratic attorneys general, environmental groups and property rights activists and are in their early stages in district courts across the country.

Annie Snider contributed to this report.

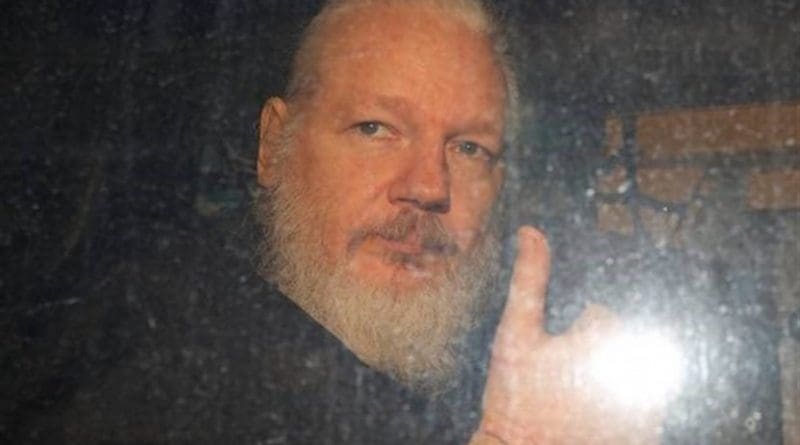

Assange’s Eighth Day At Old Bailey: Software Redactions, Iraq Logs And Extradition Act – OpEd

September 18, 2020 Binoy Kampmark

Julian Assange. Photo Credit: Tasnim News Agency

By Binoy Kampmark

The extradition trial of Julian Assange at the Old Bailey struck similar notes to the previous day’s proceedings: the documentary work and practise of WikiLeaks, the method of redactions, and the legacy of exposing war crimes. In the afternoon, the legal teams returned to well combed themes: testimony on the politicised nature of the Assange prosecution, and the dangers posed by the extra-territorial application of the Extradition Act of 1917 to publishing.

Assange the discerning publisher (for the defence) or reckless discloser (for the prosecution) were recurrent features. This time, it was John Sloboda, co-founder of the British NGO, Iraq Body Count, who took the stand. IBC had its origins in a noble sentiment: to give “dignity to the memory of those killed.” To know how loved ones perished sates a “fundamental human need”, and aids “processes of truth, justice, and reconciliation.” The outfit “maintains the world’s largest public database of violent civilian deaths since the 2003 invasion, as well as a separate running total which includes combatants.”

Central to Sloboda’s testimony was the importance of the Iraq War Logs, released in October 2010. As IBC puts it, the logs did not constitute the first release of US military data on Iraqi casualties but were pioneering, making it “possible to examine such data and to compare and combine it with other sources in a way that adds appreciably to public knowledge.” The compilation of 400,000 Significant Activity reports put together by the US Army comprised, in Sloboda’s words, “the single largest contribution to public knowledge about civilian casualties in Iraq.” They were, he told the court, “a very meticulous record of military patrols in streets in every area of Iraq, noting and documenting what they saw.” Some 15,000 previously unknown civilian deaths were duly identified.

In terms of collaboration, IBC approached WikiLeaks in the aftermath of publishing the Afghan War Diary. An invitation from Assange to join a media consortium including The Guardian, Der Spiegel and The New York Times followed. “It was impressed on us from our early encounters with Julian Assange that the aim was a very stringent redaction of documents to ensure that no information damaging to individuals was present.”

The redaction of the logs was part of a “painstaking process” that took “weeks”. Given the physical impossibility of manually redacting 400,000 documents in timely fashion, “The call was out to find a method that would be effective and would not take forever.” Sloboda made mention of a computer program developed by a colleague, one that would remove names from the documents. “It was a process of writing the software, testing it on logs, finding bugs, and running it again until the process was completed.”

The publication release was delayed, as the software in question “was not ready by the original planned publication date”. Modifications were also affected in terms of how thoroughly redaction might take place of “different categories of information”: the removal of architectural features (mosques, for instance), or expertise or professions of individuals.

Pressure was placed on WikiLeaks by the other media partners to publish. Their contribution to the redaction process had been sparse and manual: a mere sampling. Assange held firm against such impatience: redactions had to take place systematically; “the entire database,” recalled Sloboda, was “to be released together.” If anything, the final product was one of overcautious sifting, one overly pruned to prevent any dangers.

For all that, Sloboda insisted in his witness statement that a decade on, the Iraq War Logs “remain the only source of information regarding many thousands of violent civilian deaths in Iraq between 2004 and 2009.” The position of IBC was simple: “civilian casualty data should always be made public.” In doing so, no harm hard occurred to a single individual, despite repeated assertions by the US government to the contrary, not least because of the thorough redaction process. “It could well be argued, therefore, that by making this information public, [Chelsea] Manning and Assange were carrying out a duty on behalf of the victims and the public at large that the US government was failing to carry out.”

Joel Smith QC for the prosecution duly probed Sloboda on his experience in the field of classifying or declassifying documents, and whether he had earned his stripes dealing with corroborating sources in an oppressive regime. Such questioning had a simple purpose: to anathemise the civilian or journalist publisher of documents best left to agents and thumbing bureaucrats. Had Sloboda and staff at the IBC been appropriately vetted? “We paid a visit to the offices of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and were asked to sign a non-disclosure agreement with the then director Iain Overton. I don’t remember any vetting process.”

Sloboda, in his written submission, conceded that the previous publications by WikiLeaks, in particular the Afghan War Diary, came with its host of challenges, a “steep learning curve for all of those concerned.” To Smith’s questioning, he revealed that “there was a sense there needed to be a better process in the next round”, the redaction process having not quite been up to scratch.

Another line of the prosecution’s inquiry was the accuracy of the redaction. Was there human agency at any time in reviewing the war logs to avoid any “jigsaw risk” enabling the identification of individuals? Checking did take place, answered Sloboda, “but no human could go through them all.”

Smith, as with other prosecutors, persevered with the Assange as ruthless motif, this time asking if Sloboda was aware of comments allegedly made at the Frontline Club for journalists. The transcript of the event supposedly has the publisher claiming that WikiLeaks nursed no obligation to protect sources in leaked documents except in cases of unjust reprisal. “Today is the first time that I have read the transcript.” Sloboda could “remember nothing like that in our conversations about the Iraq logs.”

The possibility that Iraqi lives were probably put at risk was aired, with Smith reading a witness statement from assistant US attorney Kellen S. Dwyer that the Iraq War Logs had named local Iraqis who had been informants for the US military. (Dwyer’s competence might be gauged by the “cut and paste” mistake he made in revealing that Assange had been charged under seal.) To this unprovable assertion or assessment (qualifying risk and harm), Sloboda expressed surprise; if the reference was to “the heavily redacted logs published in October 2010, this is the first time I have heard of it.”

Human rights attorney and historian Carey Shenkman followed to testify via videolink. Shenkman, a keen student of the historical and often invidious use of the Espionage Act, was in the employ of the late and formidable Michael Ratner, president emeritus of the Center for Constitutional Rights. Shenkman’s written testimony is withering of the statute now being used with such relish against Assange.

Much said by Shenkman would be familiar to those even mildly acquainted with that period of executive overreach. It arose from “one of the most politically repressive” times in US history, a nasty product of the Woodrow Wilson administration’s fondness of targeting dissidents. “During World War I, federal prosecutors considered the mere circulation of anti-war materials a violation of the law. Nearly 2,500 individuals were prosecuted under the Act on account of their dissenting opposition to US entry into the war.” Among them were such notables as William “Big Bill” Haywood of the International Workers of the World, film producer Robert Goldstein and, with much disgrace, Eugene Debs, presidential candidate for the Socialist Party.

The word “espionage”, he explained to Judge Vanessa Baraitser, was a misnomer. “Although the law allowed for the prosecution of spies, the conduct it prescribed went well beyond spying.” The Act became the primary “tool for what President Wilson dubbed his administration’s ‘firm hand of stern repression’ against opposition to US participation in the war.”

As Shenkman noted in his statement to the court, the Act targeted spying for foreign enemies in wartime and was intended to address “such matters as US control of arm shipments and its ports”. But it also “reflected the government’s desire to control information and public opinion regarding the war effort.”

Its broadness lies in how it criminalises information: not merely “national security information” but all material falling under the umbrella of “national defence” information. Shenkman has previously argued that public interest defences focused on the positive outcomes of disclosures be given to whistleblowers and hacktivists. But for the First Amendment advocate, the Espionage Act remains fiendishly controversial when it comes to the press, the reason, he testified, why there was never “an indictment of a US publisher under the law for the publication of secrets. Accordingly, there has never been an extraterritorial indictment of a non-US publisher under the Act.”

The idea of prosecuting publishers involving grand juries had been flirted with in some cases, but never seen through. Shenkman offered a few highlights. The Chicago Tribune faced the possibility in 1942 when it published secrets after the Battle of Midway. The effort crumbled when the prosecutor in that case, William Mitchell, expressed doubts that the Espionage Act extended to newspapers. The Truman administration had also tentatively tested these waters, arresting three journalists and three government sources for conspiracy to violate the Act. No indictments followed, though it emerged that political pressure had been brought to bear on the Justice Department from “multiple factions within the Truman administration.” An uproar led to a jettisoning of the case and the imposition of small fines.

Previous examples are also noted in Shenkman’s court submission, including the threatened prosecutions of Seymour Hersh during the Ford administration, and James Bamford in 1981. Dick Cheney, future dark puppeteer of the George W. Bush administration, felt it would be “a public relations disaster” to target Hersh.

According to Shenkman, a chilling change in the winds took place during the Obama administration, if only briefly. Fox News journalist James Rosen had been named as an “aider, abettor, and co-conspirator” in a Justice Department case against Stephen Kim, a State Department employee. The effort stalled and Eric Holder’s remarks on resigning as Attorney General in 2014 spoke of deep regret that Rosen had ever been named. Journalists felt relief.

Then came the Assange indictment. “I never thought based on history we’d see an indictment that looked like this.” It was part of the Trump administration’s desire “to escalate prosecutions as well as ‘jailing journalists who publish classified information.’ The Espionage Act’s breath provides such a means.”

Prosecutor Claire Dobbin was blunter than her colleague, preoccupied with attacking Shenkman’s credibility for having worked with Ratner when representing Assange. Little time was spent on the substance of Shenkman’s submission; instead, the prosecution sought to convince the witness that the case against Assange would be best heard on US soil.

What mattered to Dobbin was taking the politics out of the prosecution. Surely, she put to Shenkman, he could still believe in 2015 that the US would bring charges against Assange. The less than subtle insinuation here is that a refusal to do so under the Obama administration was merely a lull rather than an abandonment of interest. “[O]ftentimes,” replied Shenkman, “these things are left to simmer, but ultimately, an indictment was not brought.” Had President Barack Obama and Attorney General Holder wished to pursue Assange, they would have surely shown a measure of eagerness to do so.

More could be said about the politicisation thesis: the singular use of the Espionage Act, the framing of the charges, and the timing of the indictment, all pointing to “a highly politicized prosecution.”

Prosecutorial tactics switched to hair splitting. What constituted the stealing of national security and national defence information? Would that be covered by the First Amendment? Depends, countered Shenkman, reminding Dobbin of the recent 9th Circuit Court of Appeals decision in United States v Moalin accepting the merit of Edward Snowden’s disclosures on unwarranted surveillance by the National Security Agency, despite deriving from an instance of theft.

There was a divergence of views on the issue of “hacking” as well. “Are you saying that hacking government databases is protected under the First Amendment?” shot Dobbin. Again, more clarity was needed, suggested Shenkman. The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, for instance, makes no reference to the term. Nuance is required: “crack a password’ and “hack a computer” have “scary” connotations; in other instances there would be “ways the First Amendment could be relevant.”

Given such disagreement and lack of clarity of terms, Dobbin pushed Shenkman to agree that a US court would be the most appropriate body to determine the issue. “No,” came the emphatic answer. The way the indictment had been drafted was political. The prosecution had, effectively, dithered.

Home » Assange’s Eighth Day At Old Bailey: Software Redactions, Iraq Logs And Extradition Act – OpEd

Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge.

By AMY GOODMAN and DENIS MOYNIHAN |

September 19, 2020

The role of the free press is to hold power accountable, especially those who would wage war. Press freedom itself is currently on trial in London, as Julian Assange, founder and editor-in-chief of the whistleblower website Wikileaks, fights extradition to the United States over an ever-evolving array of espionage and hacking charges. If extradited, Assange faces almost certain conviction followed by up to 175 years in prison. His unjust imprisonment would also shackle journalists worldwide, serving as a stark example to anyone daring to publish leaked information critical of the U.S. government.

U.S. prosecutors allege that Assange conspired with Chelsea Manning, a Private in the U.S. Army, to illegally download hundreds of thousands of war logs from Iraq and Afghanistan, along with a huge trove of classified cables from the U.S. State Department.

The first disclosure from this massive whistleblower release was a video that Wikileaks called “Collateral Murder.” It was recorded aboard a U.S. Apache helicopter gunship as it patrolled the skies above Baghdad on July 12, 2007. The Apache crew recorded video and audio of their slaughter of a dozen men on the ground below, including a Reuters cameraman, Namir Noor-Eldeen, 22, and his driver, Saeed Chmagh, 40. After the initial high-calibre machine gun attack, a van arrived to help the wounded. The Apache crew received permission to “engage” the van and opened fire, tearing apart the front of the vehicle, injuring two children in the van. Reuters had unsuccessfully sought the video for years.

Before long, The New York Times, The Guardian and Der Spiegel had worked together with Wikileaks and Assange, publishing stories based on the disclosures. They detailed war crimes committed by U.S. forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, torture at CIA blacksites, abuses at the U.S.’s notorious Guantanamo Bay prison camp, and cynical diplomatic dealings by State Department officials.

“It is a clear press freedom case,” Jennifer Robinson, one of Julian Assange’s attorneys, said recently on the Democracy Now! news hour. “The First Amendment is understood to protect the media in receiving and publishing that information in the public interest, which is exactly what WikiLeaks did.”

The British authorities have kept Assange in almost complete isolation in London’s high security Belmarsh prison since arresting him in April, 2019, dragging him out of the Ecuadorian embassy. Granted political asylum by Ecuador, he lived inside the dark, cramped embassy for over seven years. When a rightwing president took power in Ecuador, he revoked Assange’s asylum and allowed the arrest.

Nils Melzer, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture, visited Assange in Belmarsh, and reported afterwards, “I spoke with him for an hour…then we had a physical examination for an hour by our forensic expert, and then we had the two-hour psychiatric examination.

And all three…came to the conclusion, that he showed all the symptoms that are typical for a person that has been exposed to psychological torture over an extended period of time.”

The conditions of Assange’s imprisonment have only worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. He hasn’t spoken publicly in court, other than once, shouting “Nonsense!” in response to one of the many unsupported claims by the U.S. prosecutor. The presiding magistrate threatened to have Assange removed. Experts have lined up to defend Assange, including legendary Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg.

In 1971, Ellsberg released the Pentagon Papers, the secret history of the United States’ war in Vietnam, documenting how successive administrations had lied to the public about the war. Like Assange, he provided the leaked documents to the New York Times. Also like Assange, Ellsberg was charged under the Espionage Act, and could have spent life behind bars.

Ultimately, a judge threw out his case, when it was revealed that President Nixon had ordered criminal break-ins seeking derogatory information on Ellsberg.

In a prepared statement in Assange’s defense, Ellsberg reflected on the importance of the Wikileaks disclosures. “I consider them to be amongst the most important truthful revelations of hidden criminal state behavior that have been made public in U.S. history,” he said. “The American public needed urgently to know what was being done routinely in their name, and there was no other way for them to learn it than by unauthorized disclosure.”

Many of the war crimes exposed by Wikileaks, in cooperation with established news organizations around the world, occurred under President George W. Bush. Assange’s prosecution began under President Barack Obama. Then-Vice President Joe Biden called Assange a “high-tech terrorist.” Now, President Trump, who said during his 2016 campaign, “WikiLeaks, I love WikiLeaks,” wants to lock up Assange and throw away the key. No president, of any party, should be allowed to threaten the free press. Indeed, it is essential to the functioning of a democratic society.