McKenzie Wark

Journal #63 - March 2015

Marx: “All that is solid melts into air.”1 That effervescent phrase suggests something different now. Of all the liberation movements of the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries, one succeeded without limit. It did not liberate a nation, or a class, or a colony, or a gender, or a sexuality. What it freed was not the animals, and still less the cyborgs, although it was far from human. What it freed was chemical, an element: carbon. A central theme of the Anthropocene was and remains the story of the Carbon Liberation Front.

The Carbon Liberation Front seeks out all of past life that took the form of fossilized carbon, unearths it and burns it to release its energy. The Anthropocene runs on carbon.2 It is a redistribution, not of wealth, or power, or recognition, but of molecules. Released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, these molecules trap heat, they change climates. The end of prehistory appears on the horizon as carbon bound within the earth becomes scarce, and liberated carbon pushes the climate into the red zone.3

Powerful interests still deny the existence of the Carbon Liberation Front.4 Those authorities attentive to the evidence of this metabolic rift usually imagine four ways of mitigating its effects. One is that the market will take care of everything. Another proposes that all we need is new technology. A third imagines a social change in which we all become individually accountable for quantifying and limiting our own carbon “footprint.” A fourth is a romantic turn away from the modern, from technology, as if the rift is made whole when a privileged few shop at the farmer’s market for artisanal cheese.5 None of these four solutions seems quite the thing.

The first task of critique is to point out the poverty of these options.6 A second task might be to create the space within which very different kinds of knowledge and practice might meet. Economic, technical, political, and cultural transformations are all advisable, but at least part of the problem is their relation to each other. The liberation of carbon transforms the totality within which each of these specific modes of thinking and being could be practiced. That calls for new ways of organizing knowledge.

Addressing the Anthropocene is not something to leave in the hands of those in charge, given just how badly the ruling class of our time has mishandled this end of prehistory, this firstly scientific and now belatedly cultural discovery that we all live in a biosphere in a state of advanced metabolic rift. The challenge then is to construct the labor perspective on the historical tasks of our time. What would it mean to see historical tasks from the point of view of working people of all kinds? How can everyday experiences, technical hacks and even utopian speculations combine in a common cause, where each is a check on certain tendencies of the other?

Technical knowledge checks the popular sentiment toward purely romantic visions of a world of harmony and butterflies—as if that was a viable plan for seven billion people. Folk knowledge from everyday experience checks the tendency of technical knowledge to imagine sweeping plans without thought for the particular consequences—like diverting the waters of the Aral Sea.7] Books, 2013).] Utopian speculations are that secret heliotropism which orients action and invention toward a sun now regarded with more caution and respect than it once was. There is no other world, but it can’t be this one.8

What the Carbon Liberation Front calls us to create in its molecular shadow is not yet another philosophy, but a poetics and technics for the organization of knowledge. As it turns out, that’s exactly what Alexander Bogdanov tried to create. We could do worse than to pick up the thread of his efforts. So let’s start with a version of his story, a bit of his life and times, a bit more about his concepts, from the point of view of the kind of past that labor might need now, as it confronts not only its old nemesis of capital, but also its molecular spawn—the Carbon Liberation Front. Here among the ruins, something living yet remains.

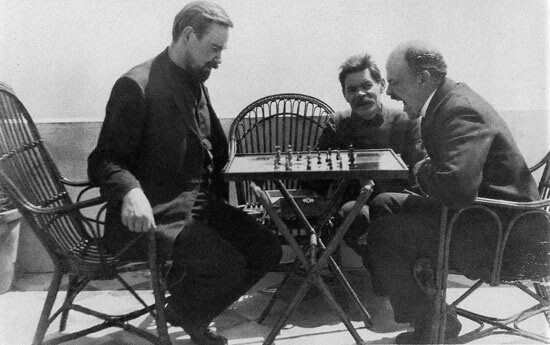

Vladimir Lenin plays chess with Alexander Bogdanov during a visit to Maxim Gorky, Capri, Italy, 1908.

Red Star and The Philosophy of Living Experience THE THREE FOUNDERS OF BOLSHEVISM

It is notable that in his 1908 science fiction novel Red Star, Bogdanov already has inklings of the workings of the Carbon Liberation Front and its relation to climate. He anticipates the possibility of Martian (and hence of human) generated climate change at a time when the theoretical possibility was starting to occur to climate scientists, even though the infrastructure did not exist yet for measuring or computing climate models.9 The Martians of Red Star already possess a global knowledge concord, frictionless data gathering, and computational power that Earthly climate science would finally acquire by the late twentieth century. With that infrastructure in place, the Martians found then what humans have found only now—that collective labor transforms nature at the level of the totality.

In his book The Philosophy of Living Experience Bogdanov is not really trying to write philosophy so much as to hack it, to repurpose it for something other than the making of more philosophy. Philosophy is no longer an end in itself, but a kind of raw material for the design and organizing, not quite of what Foucault called discourses of power/knowledge, but more of practices of laboring/knowing.10 The projected audience for this writing is not philosophers so much as the organic intellectuals of the working class, exactly the kind of people Bogdanov’s activities as an educator-activist had always addressed. Having clearly read his Nietzsche, Bogdanov’s decision is that if one is to philosophize with a hammer, then this is best done, not with professional philosophers, but with professional hammerers.

Science, philosophy, and everyday experience ought to converge as the proletariat grows. Bogdanov: “When a powerful class, to which history has entrusted new, grandiose tasks, steps into the arena of history, then a new philosophy also inevitably emerges.”11 Marx’s work is a step in this direction, but only a step. Proletarian class experience calls for the integration of forms of specialized knowledge, just as it integrates tasks in the labor process. More and more of life can then be subject to scientific scrutiny. The task of today’s thought is to integrate the knowledge of sciences and social sciences that expresses the whole of the experience of the progressive class forces of the moment.

Bogdanov: “The philosophy of a class is the highest form of its collective consciousness.”12 As such, bourgeois philosophy has served the bourgeoisie well, but the role of philosophy in class struggle is not understood by that class. It wanted to universalize its own experience. But philosophies cannot be universal. They are situated. The philosophy of one class will not make sense to a class with a different experience of its actions in the world. Just as the bourgeoisie sponsored a revolution in thought that corresponds to its new forms of social practice, so too organized labor must reorganize thought as well as practice.

The basic metaphor is the naming of relations in nature after social relations.13 It can be found “at work” in the theory of causality, the centerpiece of any worldview. Authoritarian causality had its uses: it allowed the ordering of experience, and reinforced authoritarian cooperation in production. Worldviews that assume authoritarian causes when none were observed usually invoke invisible spirit authorities as causes. Horatio obeys Hamlet; Hamlet obeys his father’s ghost. Matter is subordinated to spirit. Thus the slave model of social relations became a whole ontology of what is and ever could be.

Bogdanov makes the striking argument that religion was the scientific worldview of its time. The old holy books are veritable encyclopedias, somewhat arbitrarily arranged, on how to organize farming, crafts, sexuality or aged-care. This was a valid form of knowledge so long as an authoritarian organization of labor prevailed. But as technique and organization changed, “religious thinking lost touch with the system of labor, acquired an ‘unearthly’ character, and became a special realm of faith.”14 There was a detachment of authority from direct production. Religion then becomes an objective account of a partial world.

Bogdanov thinks it no accident that the philosophical worldviews that partially displaced religion and authoritarian causation arose where mercantile exchange relations were prevalent—among the Greeks.15 Extended exchange relations suggest another causal model, abstract causality. Buyers and sellers in the marketplace come to realize that there is a force operating independently of their will, but operating in the abstract, as a system of relations, rather than acting as a particular cause of a particular event.

Rather than such a contemplative materialism, Bogdanov, like Marx, wants an active one, an account based on the social production of human existence. Bogdanov: “Nature is what people call the endlessly unfolding field of their labor-experience.”16 Nature is the arena of labor. Neither labor nor nature can be conceived as concepts without the other. They are historically coproduced concepts.

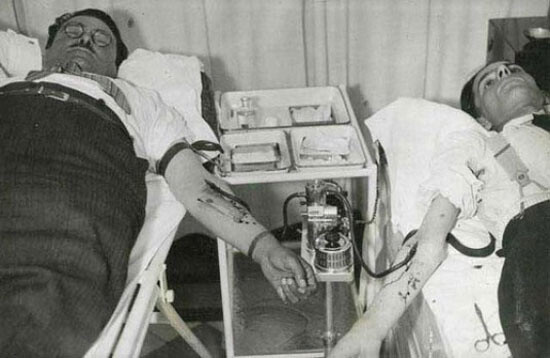

Later in his life, Bodganov was to found a research institute for blood transfusion.

The being of nature is not something a philosophy can dogmatically claim to know. It is not void, or matter, it is whatever appears as resistance in labor. Bogdanov changes the object theory from nature in the abstract to the practices in which it is encountered and known: “The system of experience is the system of labor, all of its contents lie within the limits of the collective practice of mankind.”

Take thermodynamics as an example. Industrialization runs on carbon. Demand for carbon in the form of coal meant that miners dig deeper and deeper. Pumping water out of deep mines becomes an acute problem, and so the first application of steam power was for pumping water out of mines. Out of the practical problem of designing steam-driven pumps arises the abstract principles of thermodynamics as a science.17 Thermodynamic models of causation then become the basic metaphor for thinking about causation in general, extended by substitution to explain all sorts of things.

There are at least two levels of labor activity: the technical and the organizational. Both have to overcome resistance. Technical labor has to overcome the recalcitrance of matter itself. Organizational labor has to overcome the emotional truculence of the human components of a laboring apparatus. Its means of motivation is ideology, which for Bogdanov has a positive character, as a means of threading people together around their tasks. What the idealist thinker unwittingly discovers is the labor-nature of our species-being—ideology as organization and the resistance to it—a not insignificant field of experience, but a partial one.

Before Marx, neither materialists nor idealists oriented thought within labor. The materialists thought the ideal an attribute of abstract matter; the idealists thought matter an attribute of an abstract ideal. Both suffer from a kind of abstract fetishism, or the positing of absolute concepts that are essences outside of human experience and that are its cause. Bogdanov: “An idea which is objectively the result of past social activity and which is the tool of the latter, is presented as something independent, cut off from it.”18 This abstract fetishism arises from exchange society. Causation moves away from particular authorities, from lords and The Lord, but still posits a universal principle of command.

This is why Bogdanov takes his distance even from materialist philosophy before Marx, for it still posits an abstract causation: matter determines thought, but in an abstract way. Whether as “matter” or “void,” a basic metaphor is raised to a universal principle by mere contemplation, rather than thought through social labor’s encounters with it. The revival in the twenty-first century of philosophies of speculative objects or vitalist matter is not a particularly progressive moment in Bogdanovite terms.

The labor point of view has to reject ontologies of abstract exchange with nature.19 Labor finds itself in and against nature. Labor is always firstly in nature, subsumed within a totality greater than itself. Labor is secondly against nature. It comes into being through an effort to bend resisting nature to its purposes. Its intuitive understanding of causality comes not from exchange value but from use value. Labor experiments with nature, finding new uses for it. Its understanding of nature is historical, always evolving, reticent about erecting an abstract causality over the unknown. The labor point of view is a monism, yet one of plural, active processes. Nature is what labor grasps in the encounter, and grasps in a way specific to a given situation. Marx: “The chief defect of all hitherto existing materialisms … is that the thing, sensuousness, is conceived only in the form of the object of contemplation, but not as sensuous human activity, practice, not subjectively.”20

The basic metaphor, the one which posits an image of causality, is just a special instance of a broader practice of thought. All philosophies explain the world by metaphorical substitution.21 A great example in which Marx himself participates would be the way metabolism moves between fields, from respiration in mammals to agricultural science to social-historical metabolism. Substitution extends from the experience of either nature or labor as resistance (materialism or idealism). But in either case, progress in knowledge is limited. The result tends to be the thought of activity without matter or of matter without activity. This is the problem which “dialectical materialism” imagines itself to have solved, although it has done so only abstractly.

The labor point of view calls for a thought which embodies its ambitions. Bogdanov: “Dialectical materialism was the first attempt to formulate the working-class point of view on life and the world.”22 But not the last. Strikingly, the labor point of view implies a new understanding of causality. The apparatuses of both modern science and machine production generate new experiences of causation. As in modern chemistry, labor can interrupt and divert causal sequences. Matter is not a thing-in-itself beyond experience, but a placeholder for the not-yet-experienced.

Bogdanov’s example is the concept of energy, which is neither substance nor idea but whose discovery emerges out of the practical relationship of the labor apparatus to a nature which resists it. Energy is not in coal or oil, but an outcome of an activity of labor on these materials. Bogdanov: “Labor causality gives man a program and a plan for the conquest of the world: to dominate phenomena, things, step by step so as to receive some from others and by means of some to dominate others.”23

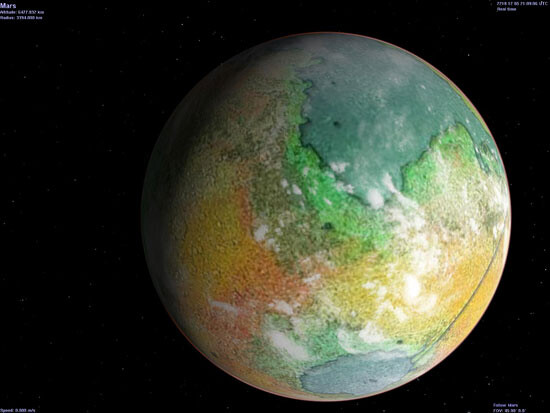

Mars One Mission is a not-for-profit independent organization that has put forward plans to bring the first humans onto Mars and establish a permanent colony there by 2025.

Return to Red Mars

Alternative futures branch like dendrites away from the present moment, shifting chaotically, shifting this way and that by attractors dimly perceived. Probably outcomes emerge from those less likely.

—Kim Stanley Robinson

“Arkady Bogdanov was a portrait in red: hair, beard, skin”—and red politics, although it will turn out that there is another kind entirely.24 He is a descendant of Alexander Bogdanov, and he is on his way to Mars, together with ninety-nine other scientists and technicians. Or one hundred others, it will turn out, when the stowaway surfaces. This First Hundred (and one) are the collective protagonist of Kim Stanley Robinson’s famous Mars Trilogy: Red Mars, Green Mars, and Blue Mars, published in the early 1990s.

If Bogdanov’s 1908 novel is a détournement of pop science fiction, then Robinson’s first part, Red Mars, is a détournement of the robinsonade, a version of Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe story. If we were to pick just one book as the precursor to capitalist realism, Crusoe might well be it. What makes it so characteristic of the genre is that it lacks any transcendent leap toward the heavens or the future. It is as horizontal as a pipeline. It is about making something of this world, not transcending it in favor of another. It makes adventure into the calculus of arbitrage, of the canny knack of buying cheap and selling dear.

In Robinson Crusoe, the shipwrecked Robinson does not depend on God or Fortune for help, he helps himself. He sets himself to work, as if he were both boss and laborer. There’s no spontaneous bravery, no tests of honor, no looking very far upwards or very far forwards. Robinson’s labors are nothing if not efficient. What is useful is beautiful on the island of capitalist realist thought, and what is both beautiful and useful is without waste. There is no room for Platonov’s fallen leaf. The world is nothing but a set of potential tools and resources.

Defoe organizes the bourgeois worldview with a forward-slanting grammar in which time is segmented and arranged serially. Robinson confronts this, does that, attains this benefit. Here’s a characteristic sentence: “Having mastered this difficulty, and employed a world of time about it, I bestirred myself to see, if possible, how to supply two wants.” Moretti: “Past gerund; past tense; infinitive: wonderful three part sequence.”25 It’s the “grammar of growth.” Bourgeois prose is a rule-based but open-ended style.

This grammar creates a whole new visibility for things. In Defoe, things can be useful in themselves. They are connectable only sideways, in networks of other things. With this you get that, with that you make this, and so on. Things are described in detail. Everything appears as a potential resource or obstacle to accumulation. What is lost is the totality. The world dissolves into these particulars. The capitalist realist self sees a world of particular things as if they were there to be the raw materials of the work of accumulation, for it knows no other kind of work.

In Red Mars, Robinson bends the robinsonade to other purposes. There is neither heaven nor horizon, but the practical question of how various ideologies overcome the friction of collaborative labor. It is not a story of an individual’s acquisition and conquest. It’s a story about collective labors. The problem here is the invention of forms of organization and belief for a post-bourgeois world. Robinson’s ambition is the invention of a grammar that might come after that of capitalist realism.

A fan representation depicts Kim Stanley Robinson's terraformed planet from the Red, Green, and Blue Mars trilogy.

In Red Star, Bogdanov’s voyager to Mars is a single representative of the most technically skilled and class-conscious workers, out to see the utopian society of labor as an already existing form. In Red Mars, on the long and dangerous voyage from Earth to Mars, and in the early days of their arrival, the First Hundred debate just exactly what it is they have been sent to organize on the “New World” of Mars. Several positions emerge, each an unstable mix of political, cultural, and technical predispositions. As in Platonov, characters each bear out a certain concept of what praxis could be. Over the course of the three books, which are in effect one big novel, these positions will evolve, clash, collaborate, and out of their matrix form the structure not just of a new polity but of a new economy, culture, and even nature.

The leaders of this joint Russian-American expedition are Maya Toitovna and Frank Chalmers, experienced space and science bureaucrats. Frank and Maya are different kinds of leaders, one cynical the other more emotive. They quickly find their authority doubled, and troubled, by more committed and charismatic potential leaders, Arkady Bogdanov and John Boone. Bogdanov and Boone overidentify with the political ideologies of their respective societies, Soviet and American, the Marxist and the liberal.26 They actually believe! Chalmers and Toitovna find this especially dangerous to their more pragmatic authority.

These four could almost form a kind of “semiotic rectangle,” an analytic tool used by both Fredric Jameson and Donna Haraway.27 It’s tempting to reach into the bag of tricks of formal textual analysis and run the Mars Trilogy through the mesh of such devices. The problem is that Robinson already includes such devices within the text itself. The character of Michel the psychiatrist is particularly fond of semiotic rectangles, for example. The usual “innocence” of the text in relation to the formal critical method no longer applies here—Robinson did, after all, study with Fredric Jameson. Perhaps that’s why Robinson always seems to want his stories to exceed the formal properties of such a schema. Rather, his characters form loose networks of alliance and opposition, always making boundaries and linkages. The novel tracks one possible causal sequence in a space of possibilities. There’s no single underlying design.

Complicating the four points of the semiotic rectangle of Maya and Frank, Arkady and John, are three outlier figures: Hiroko Ai, who runs the farm team; the geologist Ann Claybourne; and Saxifrage Russell, the physicist. Hiroko, Ann, and Sax are different versions of what scientific and technical knowledge might do and be. Hiroko’s shades off into a frankly spiritual and cultish worship of living nature. Ann’s is a contemplative realism, almost selfless and devoted to knowledge for itself. Sax sees science not as an end in itself but a means to an end—“terraforming” Mars.

Robinson did not coin the term “terraforming,” but he surely gives it the richest expression of any writer.28 While there is plenty in the Mars Trilogy on the technical issues in terraforming Mars, Robinson also uses it as a Brechtian estrangement device to open up a space for thinking about the organization of the Earth.29 On Mars, questions of base and superstructure, nature and culture, economics and politics, can never be treated in isolation, as all “levels” have to be organized together. Maya: “We exist for Earth as a model or experiment. A thought experiment for humanity to learn from.”30 Perhaps Earth is now a Mars, estranged from its own ecology.

Of the First Hundred, Arkady Bogdanov has the most clearly revolutionary agenda, and one straight out of proletkult. He objects to the design for their first base, Underhill:

with work space separated from living quarters, as if work were not part of life. And the living quarters are taken up mostly with private rooms, with hierarchies expressed, in that leaders are assigned larger spaces … Our work will be more than making wages—it will be our art, our whole life … We are scientists! It is our job to think things new, to make them new!31

There are many actually existing, contemporary or historical societies that for Robinson exude hints of utopian possibility: the Mondragon Co-ops, Yugoslav self-management, Red Bologna, the Israeli kibbutz, Sufi nomads, Swiss cantons, Minoan or Hopi matriarchies, Keralan matrilineal land tenure. One of the more surprising is the Antarctic science station. This he experienced first-hand in 1995 on the National Science Foundation’s Artists and Writer’s Program.32

Robinson imagines the first Mars station at Underhill as just like a scientific lab—and just as political. As Arkady would say, ignoring politics is like saying you don’t want to deal with complex systems. Arkady: “Some of us here can accept transforming the entire physical reality of this planet, without doing a single thing to change ourselves or the way we live … We must terraform not only Mars, but ourselves.”33 Thus the most advanced forms of organization can be a template for the totality.

A field station like Underhill is not only an advanced social form, for Arkady it connects to a deep history:

This arrangement resembles the prehistoric way to live, and it therefore feels right to us, because our brains recognize if from three million years of practicing it. In essence our brains grew to their current configuration in response to the realities of that life. So as a result people grow powerfully attached to that kind of life, when they get a chance to live it. It allows you to concentrate your attention on the real work, which means everything that is done to stay alive, or make things, or satisfy our curiosity, or play. That is utopia … especially for primitives and scientists, which is to say everybody. So a scientific research station is actually a little model of prehistoric utopia, carved out of the international money economy by clever primates who want to live well.34

Not everyone has ever got to live such a life, even at Underhill, and so the scientific life isn’t really a utopia. Scientists carved out refuges for themselves from other forms of organization and power rather than work on expanding them. The crux of the “Bogdanov” position in the Mars Trilogy is making the near-utopian aspect of the most advanced forms of collaborative labor a general condition.

This Arkady Bogdanov, not unlike the real Alexander Bogdanov a century before him, is a kind of sacrifice to the revolution. Nearly all of the early leaders fall, in one way or another, and not least because they are too much the products of the old authoritarian organizational world. Mars has to transform its pioneers, or nurture new ones, on the way to another kind of life. A new structure of feeling has to come into existence, not after but before the new world. This is what Alexander Bogdanov thought was the mission of proletkult. Overcoming the logic of sacrifice is not the least of its agenda.35

John Boone, meanwhile, finds many of Arkady’s ideas wrong, and even dangerous. John Boone is a charismatic, hard-partying Midwesterner. He is politically cautious, but acknowledges that “everything’s changing on a technical level and the social level might as well follow.”36 His mission, at first, is to forget history and build a functioning society. But while dancing with the Sufis, he has his epiphany: “He stood, reeling; all of a sudden he understood that one didn’t have to invent it all from scratch, that it was a matter of making something new by synthesis of all that was good in what came before.”37 Bogdanovists are modernists who start over; Booneans are détourners of all of the best in received cultures. Boone practices his own style of détournement, copying and correcting, and tearing off enthusiastic speeches:

That’s our gift and a great gift it is, the reason we have to keep giving all our lives to keep the cycle going, it’s like in eco-economics where what you take from the system has to be balanced or exceeded to create the anti-entropic surge which characterizes all creative life … 38

The crowd cheers, even if nobody quite understands what Boone is talking about.

Saxifrage Russell is a more phlegmatic kind of scientist, entranced by the this-ness, the “haecceity,” of whatever he happens to be working on.39 For Sax, the whole planet is a lab, and when John Boone asks him, “who is paying for all this?” Sax answers: “The sun.” Sax quietly ignores the heavy involvement of metanational companies, for whom the whole Mars mission is a colonization and resource extraction enterprise. When John later uses this same answer to Arkady, the latter won’t have it: “Wrong! It’s not just the sun and some robots, it’s human time, a lot of it. And those humans have to eat …”40 Like Arkady, Sax sees science as a component of a larger praxis of world building, but for Arkady there’s still more. There’s the question of what kind of world and who it is for—the question of the labor component of the cyborg apparatus.

For Sax, science is creation. “We are the consciousness of the universe, and our job is to spread it around, to go look at things, to live wherever we can.” Ann the geologist disagrees. “You want to do that because you think you can … It’s bad faith, and it’s not science … I think you value consciousness too high and rock too little … Being the consciousness of the universe does not mean turning it into a mirror image of us. It means rather fitting into it as it is.”41 But what does it mean, to “fit in,” when the fitting changes what it is in? Is it not metaphorically more like a refraction?

Ann’s is the most “flat” ontology of the First Hundred.42 Human subjectivity has no privilege in her world, and neither does life. The real for her is this: “The primal planet, in all its sublime glory, red and rust, still as death; dead; altered through the years only by matter’s chemical permutations, the immense slow life of geophysics. It was an old concept—abiologic life—but there it was, if one cared to see it, a kind of living, out there spinning, moving through the stars that burned …”43 If the basic metaphor for Hiroko is that life is spirit, and for Sax that life is development, for Ann it is at best selection, the lifeless life of impacts and erosions of the geological eons.

Later, Robinson compares Ann’s relation to Mars to that of a caravan of itinerant Arab miners: “They were not so much students of the land as lovers of it; they wanted something from it. Ann, on the other hand, asked for nothing but questions to be asked. There were so many different kinds of desire.”44 For the miners, nature is that which labor engages; for Ann, nature is that which appears to science only, shorn of any wider sense of praxis. Ann’s worldview is not so entirely selfless, with its “concentration on the abstract, denial of the body and therefore of all its pain.”45 Nevertheless it does speak to an absolute nonhuman outside to knowledge, an outside that even Sax will eventually have to acknowledge.

While also technically trained, Hiroko is more of a mystic. She believes in what Hildegard of Bingen called viriditas, or the greening power. This is the key to her aerophany, her landscape religion. Hiroko: “There’s a constant pressure, pushing toward pattern. A tendency in matter to evolve into ever more complex forms. It’s a kind of pattern gravity, a holy greening power we call viriditas, and it is the driving force of the cosmos …”46 Arkady wants a kind of work beyond its alienation in wage labor; Hiroko wants work to be a kind of worship. As with Ann, Hiroko has a kind of ontology, but a vitalist and constructivist one, oriented to a practice that transforms its object.47 In each case it’s a substitution, which starts with a kind of labor and imagines a universe after its basic metaphor.

There’s a constant play in the Mars Trilogy between what is visible and what it hidden. Hiroko hides Coyote, the stowaway, and herself goes into hiding, with her followers, on Mars. She asks Michel the psychotherapist to go with them when they leave the Underhill base and set up a secret sanctuary:

We know you, we love you. We know we can use your help. We know you can use our help. We want to build just what you are yearning for, just what you have been missing here. But all in new forms. For we can never go back. We must go forward. We must find our own way. We start tonight. We want you to come with us.”

And Michel says, “I’ll come.”48

When Hiroko, the Green Persephone, surfaces again, her actions require some justifying: “We didn’t mean to be selfish … We wanted to try it, to show by experiment how we can live here. Someone has to show what you mean when you talk about a different life … Someone has to live that life.”49 This is another tension in the Mars Trilogy: between political struggle and the enactment of another life directly, in the everyday, as experiments in self-organization that create new structures of feeling.

In the color scheme of the books, Hiroko stands for Green and Ann for Red. To estrange us a little from what we think these colors mean, the Greens are those who favor one or other kind of terraforming, to artificially make a biosphere for life. For the Greens, nature is synonymous with life. For the Reds, nature is prior to life, greater than life. “Ann was in love with death.”50 The Red Mars isn’t really a living one, and the Green one is more like a garden or a work of art—culture. Neither are an ecology, if by that one means some ideal model of a homeostatic, self-correcting world. For the Greens, nature is that with which one works; for the Reds, it is that which one contemplates.

Part of the problem is working up an organizational language adequate to techno-science, or as Boone says to Nadia Chernishevsky the engineer: “Muscle and brain have extended out through an armature of robotics that is so large and powerful that it’s difficult to conceptualize. Maybe impossible.” Life is a tektological problem, lived against external constraints, but as Frank despairs, “they lived like monkeys still, while their new God powers lay around them in the weeds.”51

A stereo image shows a patch of pebbles, dust, and a scrap of distressed plastic—trash on Mars of unspecified origin—photographed using Curiosity's Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI). NASA speculates that the plastic was part of the delivery vehicle, presumeably shredded during landing.

It is like Platonov’s tragedy of nature and technology in a different mode. The potential of technical power far outstrips organizational forms or concepts, which remain narrowly acquisitive and instrumental. They are on Mars to prepare the way for corporate resource extraction, after all. This is the driving tension of the Mars Trilogy. All of the experiences of Mars, through study, work, or worship, are fragments of a new ingression, but they have to link together, overcome their boundaries, and form a new boundary against the exploitative and militarized forms of life that sent them all there. But crucially in Robinson, not only is a potential politics (Arkady and John) counterposed to an actual one (Frank and Maya), but a potential technics is counterposed to the actual one of the metanationals (with the Sax character moving from the one to the other). The struggle for utopia is both technical and political, and so much else besides.

The first Martian revolution—there will be three—is in a sense against “feudalism,” against a residual part of the social formation based on self-reproducing hierarchies. It is a revolution against a world where the ruling class, like the Khans of Kiva, is impoverished by its distance from any real work—in this case an interplanetary distance. It arises out of the conflict that pits the First Hundred, leading the Martian working class, against the metanational corporations and their private armies. As Frank Chalmers says: “Colonialism had never died … it just changed names and hired local cops.”52 To the metanats, Mars has no independent existence. To the Martians, it’s a place where the apparent naturalness of the old economic order is exposed as artifice, inequality, and fetishism.

The first revolution founders. It’s vanguard is poorly coordinated, and relies too much on force, in a situation where the population in revolt is now heavily dependent on vulnerable infrastructure, which turns out to be egressive and fragile. The metanats and their goons need only shut down life support to bring refractory populations to heel. Bogdanov’s law of the minimum applies here. The movement is forced underground. But perhaps this same technoscience can also support autonomous spaces outside the metanat order, where new kinds of everyday life and economic relation might arise.

The first revolution is perhaps their 1905 Russian Revolution, although as Frank says, “Historical analogy is the last refuge of people who can’t grasp the current situation.”53 The first revolution results in a treaty of sorts, negotiated by Frank, the cynical and pragmatic politician. For Frank, “the weakness of businessmen was their belief that money was the point of the game.”54 Sax at this point still wants metanat investment, but Frank wants to contain it. As Frank says to Sax: “You’re still trying to play at economics, but it isn’t like physics, it’s like politics.”55 Science and capital, it is clear to Frank but not yet to Sax, are not natural allies.

In defeat, Arkady and the Bogdanovists will hide in plain sight, to continue the revolution of everyday life: “Why then we will make a human life, Frank. We will work to support our needs, and do science, and perhaps terraform a bit more. We will sing and dance, and walk around in the sun, and work like maniacs for food and curiosity.” They will create the counter-spectacle of an underground as a “totalizing fantasy,” onto which everyone projects their wants.56 It is a matter of making extravagant proposals for another life with enough serious seduction to draw bored and disaffected labor into believing in it.57

Failure to spark a global revolution on Mars prompts a kind of theoretical introspection, not unlike the ones that happened after the failure of world proletarian revolution in early twentieth-century Earth, and which resulted in the theoretical reflections of Western Marxism.58 It is neatly captured in a dialogue between Frank Chalmers and his assistant:

“How can people act against their own obvious material interests?” he demanded of Slusinki over his wristpad. “It’s crazy! Marxists were materialists, how did they explain it?”

“Ideology, sir.”

“But if the material world and our method of manipulating it determine everything else, how can ideology happen? Where did they say it comes from?”

“Some of them defined ideology as an imaginary relationship to a real situation. They acknowledged that imagination was a powerful force in human life.”

“But then they weren’t materialists at all!” He swore with disgust. “No wonder Marxism is dead.”

“Well, sir, actually a lot of people on Mars call themselves Marxists.”59

Most Western Marxists thought ideology in its negative aspect, its misrecognition; Bogdanov was more interested in its affirmative aspect, in the way an ideology overcomes resistance to a given form of social labor.60 From that point of view what matters in this exchange is the form of the dialogue between Frank and Slusinki—master and servant—rather than the content—a Marxisant critique of ideology. The Martians do not yet have a form of communication that express the organizational style of their emergent social formation. The problem is not with the language or the theory, its with the forms of organization and communication. The failure of this revolution does not call for the Western Marxist turn to the superstructures, but rather a Bogdanovite turn to evolving new forms of organization, including a new infrastructure.

The Martians are not ready for their revolution. Still, even an unsuccessful struggle can create powerful structures of feeling, which may have future uses. “Arkady answered them all cheerfully. Again he felt that difference in the air, the sense they were all in a new space together, everyone facing the same problems, everyone equal, everyone (seeing a heating coil glowing under a coffee pot) incandescent with the electricity of freedom.”61 As Platonov says, we are comrades when we face the same dangers.

This text is an edited excerpt from McKenzie Wark's book Molecular Red: Theory for the Anthropocene, forthcoming in April 2015 from Verso.

McKenzie Wark (she/her) teaches at The New School and is the author, most recently, of Capital is Dead (Verso, 2019) and Reverse Cowgirl (Semiotext(e), 2020).

© 2015 e-flux and the author