LEFT BOLSHEVISM

The Stofflichkeit of the Universe: Alexander Bogdanov and the Soviet Avant-Garde

Prelude: Towards an Alternative Philosophical Genealogy of the Soviet Avant-Garde

Maria Chehonadskih

e-flux

Journal #88 - February 2018

One of the most discussed concepts of the Soviet avant-garde—variously characterized as “construction,” “tectonics,” “production,” or “life-building”—may seem to refer simultaneously to the formalist method in art and to a theory of social constructivism that departs from the idea of the “new Soviet man” and ends up with Stalin’s “engineers of the human soul.” The simultaneity of formalism and social constructivism normally explains the coexistence of the constructivist aesthetic program and the utilitarian politics of productivist art. As Benjamin Buchloh writes, constructivism passes from the expanded modernist aesthetics that “did not depart much further from the modernist framework of bourgeois aesthetics than the point of establishing models of epistemological and semiotic critique,” to the new industrialized forms of art.1 Optimism about technology and media leads constructivists to totalitarian Stalinism.2 Yve-Alain Bois goes so far as to argue that the total instrumentalization of art is inevitable when the critical modernist tradition is abandoned.3 In other words, the great achievements of the Soviet avant-garde conform to the standards of European modernist epistemologies, while utilitarian aesthetics and its function in the context of Stalinism signifies a break or a black hole, which the narrative of art history can only explain by turning to ethical and moral arguments against propaganda and instrumentalization. An alternative proposition would be to examine the philosophical core of the constructivist and productivist programs and rethink their epistemological foundation.

The confusion regarding the constructivists’ construction and the productivists’ production comes from a false genealogical attribution of these concepts to formalism and social constructivism. What has to be accounted for, and what is normally ignored, is the background of what I term “Empirio-Marxism.” The interest in empiricism among the pre- and postrevolutionary Marxists of the Russian Empire and the Soviet state is mainly known though Lenin’s famous Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, the book in which he accuses Bolshevik activist and philosopher Alexander Bogdanov of deviating from Marxism and of providing reactionary support for idealist philosophy.4 Indeed, Bogdanov brings together the notorious empiriokritizismus and the early Bolsheviks’ understanding of Marx to first propose the philosophy of “empiriomonism” (1900s)5 and then the universal science of organization, or “tektology” (1910s).6 Both doctrines correspond to the political idea of proletarian culture, implemented in the Proletkult (Proletarian Cultural-Enlightenment Organizations) movement after the October Revolution in 1917. Bogdanov, a principal theoretician of the movement, develops a conception of experience as a homogeneous field of collective praxis.

This is not an obvious reference point in relation to Russian avant-garde artists, since in their work there is no consistent presence of the problem of experience. There are no overt references to empiricism, Mach, or Bogdanov in the published archive of the Soviet avant-garde. It was more common to praise Lenin, and one can easily recall Dziga Vertov’s “Three Songs About Lenin” or Alexander Rodchenko’s “Worker’s Club,” with a portrait of the leader of the proletariat on a wall. Nonetheless, Empirio-Marxism was a very popular local tradition and Bogdanov had a greater intellectual authority in the art community due to his establishment of Proletkult. There are no official portraits of Bogdanov, but his philosophy in fact populates every single art-related book. This has been acknowledged only in Soviet publications, where avant-gardism is associated exclusively with Bogdanov’s ideas and political views.7 Nevertheless, it is also a very well-known fact that writer and engineer Andrei Platonov was a member of the Proletkult,8 and that the main theorist of productivist art, Boris Arvatov, worked as secretary of the Moscow Proletkult, while Rodchenko, Tretyakov, and Eisenstein, among others, collaborated with Proletkult studios.9 This fact has never led English-speaking theorists to examine closely Bogdanov’s philosophy or at least to consider Proletkult as an important intellectual and political reference. What I aim to discuss here is to what extent Bogdanov’s philosophy mediates methodologies of constructivism and productivism, and how these movements in turn radicalize and shift the philosophical and political claims of Bogdanov and the Proletkult.

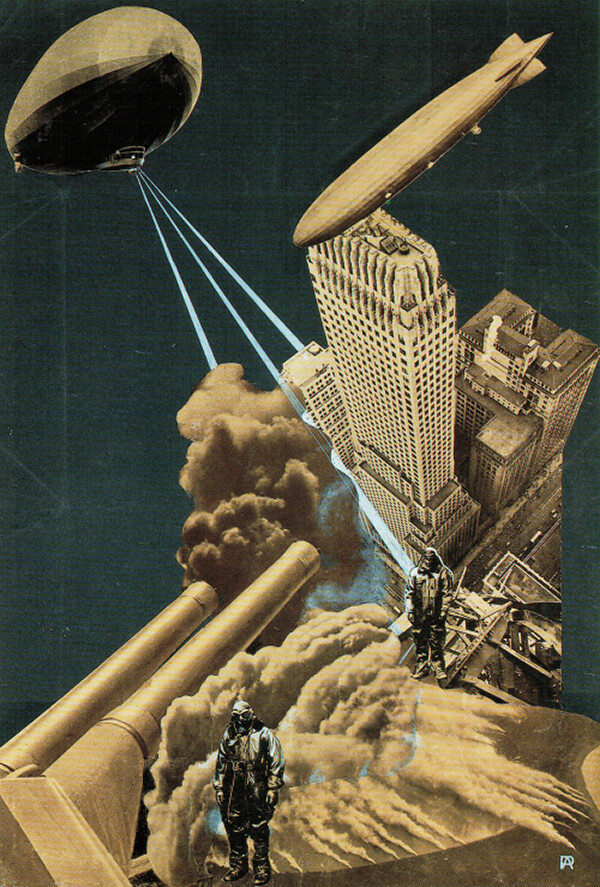

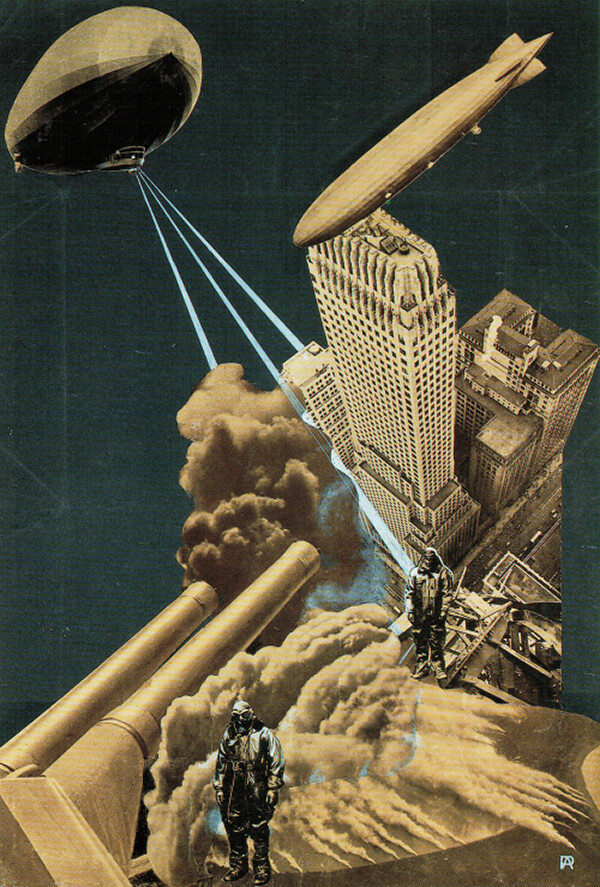

Alexander Rodchenko, War of the Future, 1930. Magazine illustration.

Bogdanov’s Ontology of Organization and the Art of World-Building

Bogdanov’s conception of organization rests on a basic empiricist assumption that experience of the outside world is given to us in the conjunctions of an object’s attributes. The decomposition of these attributes gives elementary sensations of space, time, color, form, and size. However, the elements of experience are sensations only in psychical reality, whereas the same elements may belong to physical bodies as attributes—the squareness and redness of a brick are the sensual, perceptible, physical properties of this object.10 The connection between the psychical and physical realms should be understood as a complex unity that unfolds as an exchange of sensations and properties within an environment that is itself neutral to this subject-object distinction. In other words, there is no sovereignty of a knowing subject who reflects on objects outside it, because there is no outside. This subject is already an object, a complex product of exchanges between physical and psychical elements. Ontologically, this exchange produces a series of “life-complexes” (forms of life, including social forms); and epistemologically, it constitutes a monist point of view on the otherwise heterogeneous self-organizing flow of psychical and physical concatenations: “The universe presents itself to us as an endless flow of organising activity. The ether of electrical and light waves was probably that primeval universal environment from which matter with its forces—and later on also life—crystallised.”11

Bogdanov’s empiriomonism tends to reformulate the biological and the social in terms of the organizational logic of psychophysical complexes. Taken as isolated entities, psychic and physical complexes exist in a pure state of spontaneity, or the lowest level of organization. This spontaneity preserves higher organizational forms only in analysis and in the practical composition of the elements into new series. A rock is a spontaneously formed physical combination of minerals, and fear is a spontaneously formed psychical combination of stimuli and reaction. But the fear of wild animals that leads to the construction of a house made out of rock is a product of a higher psychophysical organization.

As we can see, the psychophysical complexes are constructed first in labor activity. In the wake of the rise of labor technics, the sum of the elements grows, but their usage depends on “technical and cognitive goals.”12 The laboring subject appeals either to actions or to the attributes of objects out of necessity. Splitting and crushing, for example, led to the invention of the concept of the atom.13 Labor’s use of the elements of experience—be it a rock in construction, or ore in industry, or oil in painting, or the concept of the atom in philosophy—corresponds to use value, on the grounds that it emerges from a social need to distinguish and differentiate experience in order to develop production—domestic, industrial, scientific, or artistic. In Bogdanov, use value appears as an ontological principle of usefulness, and value as an essentially vitalist quality.14 This process of extracting, shaping, and composing the elements of experience into life-complexes, Bogdanov identifies with Marxian Verdinglichung (reification).15

This means that the object, or rather the organization of objects, is a historically produced system of relations. The ready-made object is the work in progress of laboring humanity:

The practice of this great social organism is nothing other than world-building … This world, which has been constructed and continues to be under construction … is the most grandiose and perfected that we know … Such is our picture of the world: an unbroken series of forms of organization of elements—of forms that develop in struggle and interaction without any beginning in the past, without any end in the future.16

Any kind of social practice is the labor of organization, or the labor of world-building. That is why Bogdanov’s theory of art corresponds to the same organizational ontology:

Artistic creativity, combined and often alloyed with cognition, as may be seen in many pieces of belles-lettres, poetry and painting, organizes understanding, feelings and emotions by its own methods. In art the organization of ideas and the organization of things are inseparable. For instance, an architectural construction, a statue, or a painting as they are, might be regarded as systems of “dead” elements—of stone, metal, canvases and paint; but the lively meanings of pieces of art belong to the complexes of images and emotions to which they give life in a human psyche.17

Art is one of the many forces within the logic of organization. However, only collectivized proletarian labor produces the art of total organization. The proletariat brings elements of the “lowest” life in nature and “unconscious” life in society to the noncontradictory and rational form of psychophysical unity. Bourgeois culture is based on competition and exploitation, and as a result, on the production of conflicting partial systems. To make an exit from partial irrational systems, such as capitalism, would mean to construct a new totality; some names for this new totality are “universal organization,” “classless society,” and “proletarian culture.” The highest degree of organization is a homogeneous wholeness based on unified industrial labor, solidarity, comradeship, and collectivization.18

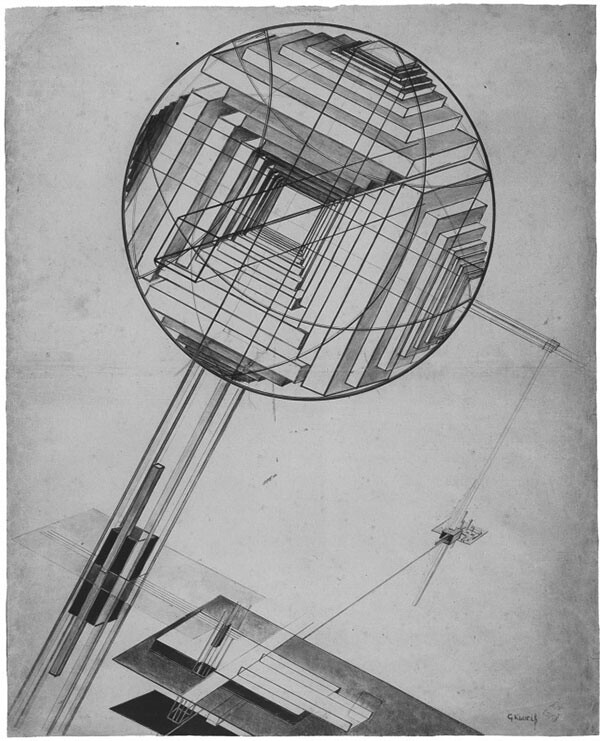

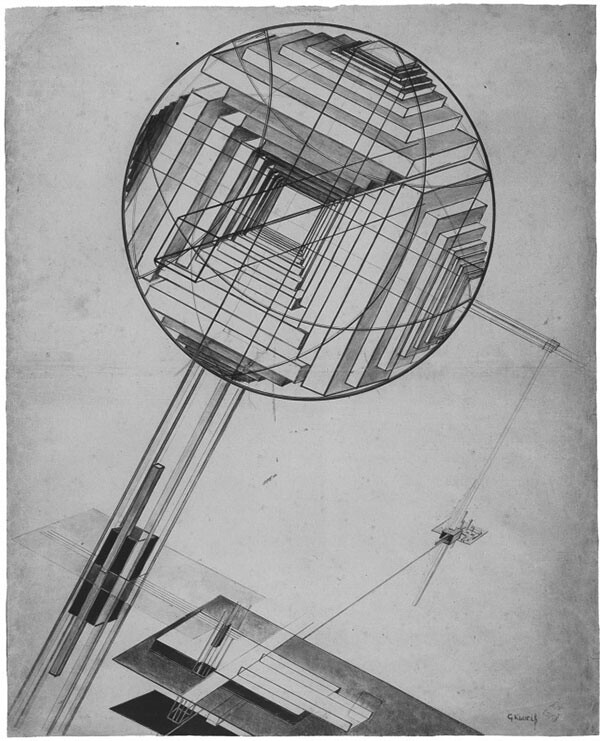

Gustav Klutsis, Construction, 1921.

World-Building Abolishes Art: Construction, Production, and Organization in the Avant-Garde

It is not hard to see how Bogdanov’s world-building is close to the productivist figures of the “life-builder” and “engineer-constructor.” Art is a labor of shaping and composing an object according to the usefulness of a color and a form, writes Osip Brik.19 In the manifesto “Constructivism,” Alexei Gan provides a three-page-long quotation from Bogdanov to support an argument about the importance of organization and production. Gan claims that material production replaces representational art. This new mode of production saves the “solid material and formal foundations of art, such as line, flatness, volume, and action,” along with the purposeful activity of “materialistically grounded” artistic labor. Constructivism is Bogdanov’s organizational science, which seeks a form of “organization and cementation for the mass labor processes, mass actions in the whole of social production.”20 This may lead to the conclusion that the three famous disciplines of constructivism—construction, facture (faktura), and tectonics—fully correspond to the principles of organization. It has even been argued that tectonics is a cipher for tektology.21 Bogdanov’s philosophy seems to be foundational, and one can read the theory of constructivism back into empiriomonism and tektology: faktura is the process of extracting and manufacturing the elements of nature, while construction is the aggregation of the complexes of elements into a purposeful organizational plan—tectonics. The organizational point of view appeals to Nikolai Chuzhak as a grandiose cosmogony of all-embracing life-building:

People who look at art from the point of view of communist monism inevitably come to the conclusion that art is only a quantitatively individual, temporary, and predominantly emotional method of life-building, and, as such, cannot remain isolated, or what is more, self-sustaining compared with other approaches to life-building.22

A similar Bogdanovian detour into the various currents of art practice, albeit more grandiose still, was that of the Proletkultist Boris Arvatov. In Art and Production, at once a presentation of research and an energetic manifesto, the history of art is shown to unfold within the terms of Bogdanov’s history of labor. According to this narrative, art has always been a part of production: for instance, crafts, frescos, and architecture served the everyday needs of premodern societies. However, under the rule of capitalism, art becomes instead an individualistic, self-organizing activity. Easel painting is one significant example of the contemplative representational function of art in bourgeois society. Arvatov seeks the new forms of a “proletarian monism” in which the productive capacity of art to shape the environment can be restored.23 The figure of the engineer-constructor expresses the unity of invention and construction in creating a new “form of being,” or communism.24 The construction of the new elements of experience—a.k.a., the labor of organization—gives art a place in production. In other words, it makes art productive.

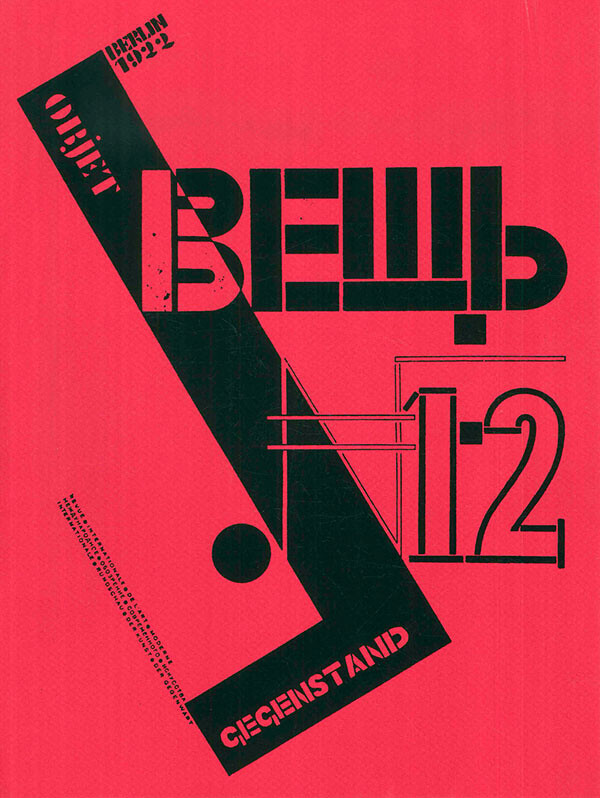

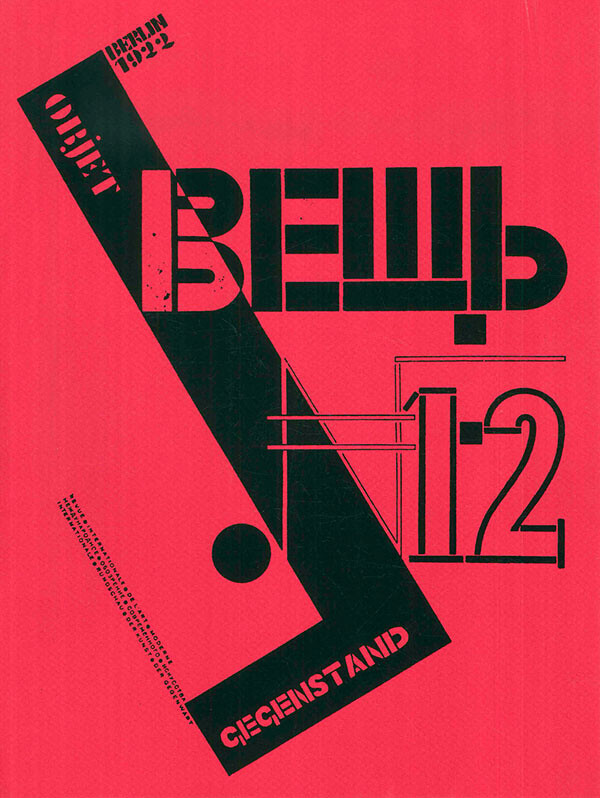

Cover of the journal Veshch/Gegenstand/Objet (1922), edited by El Lissitzky and Ilya Ehreburg.

If constructivism and productivism are oriented towards the production of new forms of being and communist world-building, the task of art, according to Bogdanov, is less radical and much more modest. Art is the education of the senses. It organizes feelings and emotions into images and forms. The “unity of form and content,” “harmony,” and “creativity” are epithets that Bogdanov uses to discuss proletarian art.25 Despite the contradiction between the enormous ambitions of the artistic avant-garde and the modest role of art in Bogdanov’s system, the theorists of constructivism and productivism tried to reinterpret Bogdanov’s organization of the senses for their own benefit. Nikolai Tarabukin understands the organization of emotions in empiricist terms, as the orientation of a subject in its natural and social environment. An artist does not copy but organizes nature on the canvas, building a landscape according to compositional laws. Painting establishes a particular “point of view” for the perceiving viewer. “The artist is the organizer of our visual orientation,” concludes Tarabukin.26 Chuzhak also accepts the emotional concept of art: “Art is an original, mainly emotional (only mainly and it only differs from science in this advantage) dialectical approach to life-building.”27 The content of the constructivist “dialectical modelling” consists of “the tangible thing” and “the idea, the thing in its model.”28

In an early Proletkultist article entitled “Proletarian Poetry” (1922), Andrei Platonov states that proletarian art has to begin with the organization of “immaterial things”—images and symbols of things; or simply put, words. He distinguishes three elements of a word: idea, image, and sound. The organization of poetry according to the triangular properties of a word is the process of gathering all wandering feelings and senses into one thought. The word-becoming of thought penetrates reality better than empty abstractions, because it makes conscious both sensibility and proletarian experience. From the organization of triangular words into thoughts, humankind will proceed to the organization of matter and world-building.29

The triangular words of Platonov recognize only proletarian experience; they materialize in words the “troubled” sound of the “gurgling of acid and alkaline grasses being digested in [the] stomachs” of the proletariat.30 Triangular words may also prove that a thought is the process of material production through “a certain pressure in the dark warmth.”31 This is the point of view of labor experience, the articulation of what is seen and what happens from the perspective of a laboring body: it speaks as it labors. Triangular words are material as much as immaterial, since they are embodied in the experience of the laboring proletariat. Platonov writes “not with words, imagining and copying real living languages, but rather with pieces of living language.”32 Similarly, Dziga Vertov writes “kino-thing[s] via filmed frames” and creates “visual thinking.”33 This art of seeing organizes the chaos of impressions into a new “class vision.”34 This does not mean that Vertov and Platonov prefer a naturalistic photographic copy of reality. Instead, they produce reality, or better yet, the universal point of view of the laboring population of the earth.

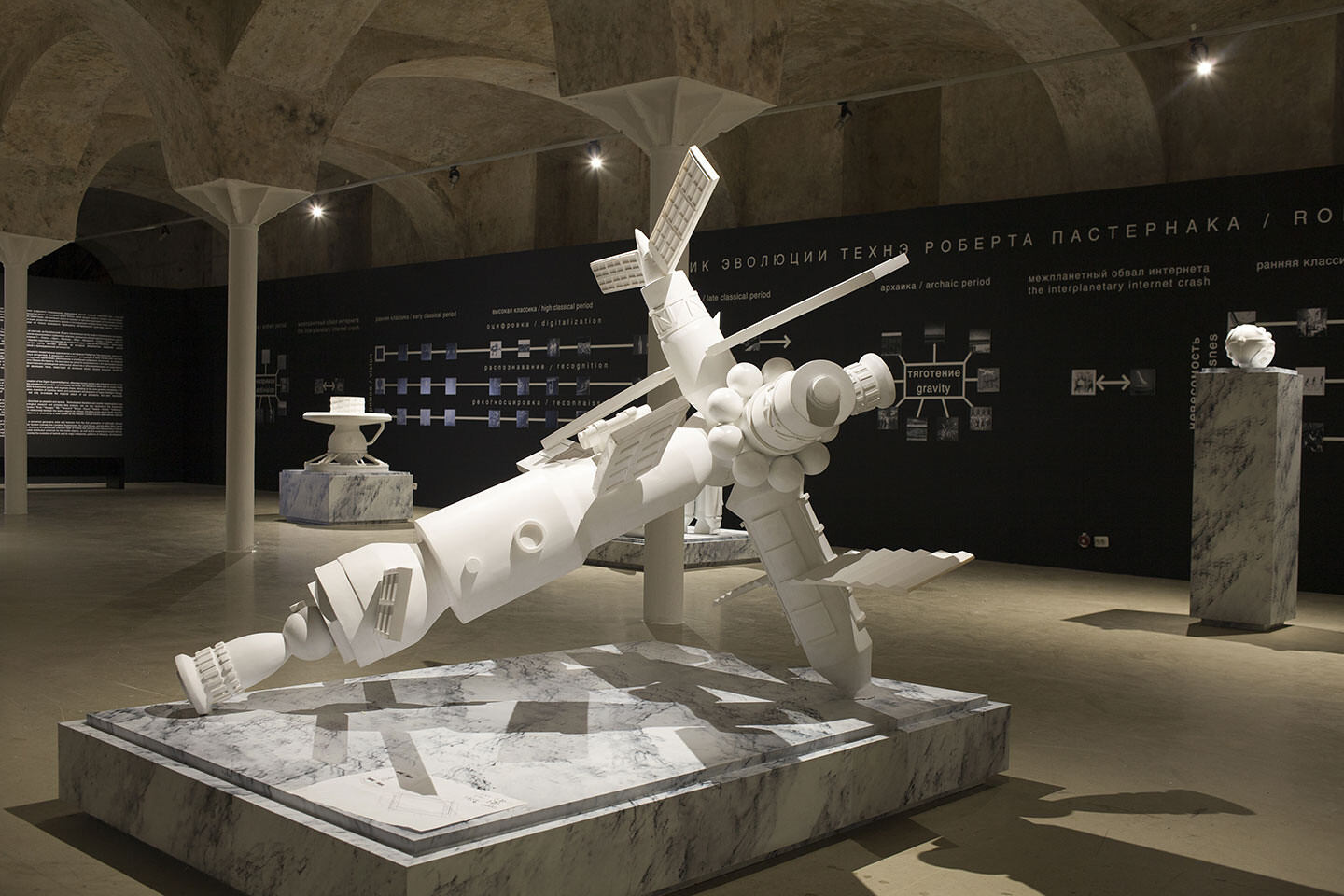

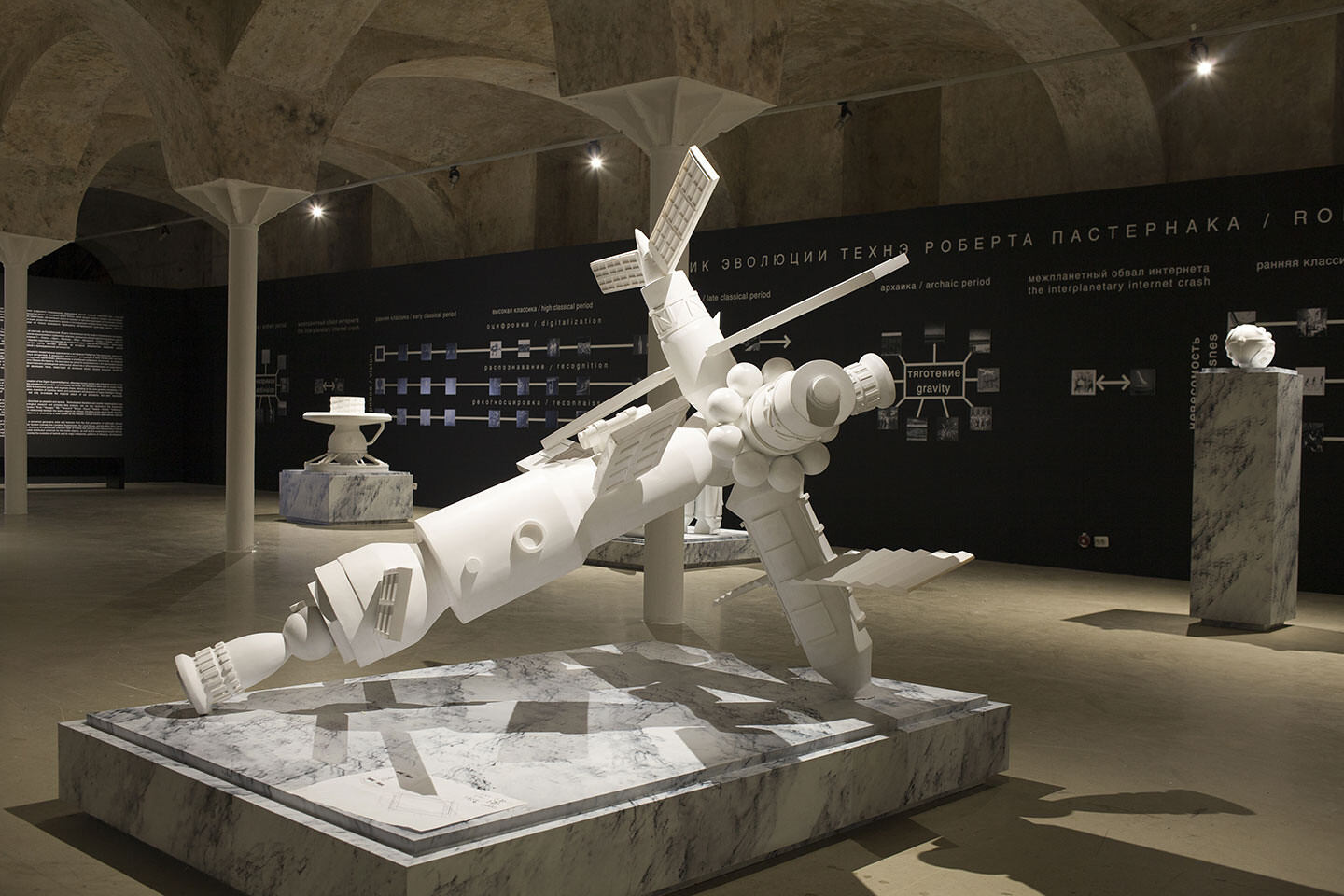

Arseny Zhilyaev, Return, 2017. Installation view.

The Stofflichkeit of the Universe: Platonov and the Thinghood of a Thing

The organization of the sensible is already the organization of matter, since the sensible is embodied proletarian experience. That is why the nature of psychophysical elements—those unities of experience—occupies Platonov as much as the materiality of words and sounds. In his science fiction story The Impossible (1921), he writes:

The Swedish physicist Arrhenius has a beautiful, amazing hypothesis concerning the origin of life on the earth. It is his guess that life is neither a local nor a terrestrial phenomenon. It has been transported to us from other planets through enormous ethereal spaces in the form of the smallest and most elementary colonies of organisms … Perhaps atoms, and atoms of atoms—electrons—are the same microorganism, but only in its limited, initial form.35

Similar reflections about atoms and electrons are repeated by the scientist Popov in Platonov’s science fiction story “Ethereal Tract.” Popov’s theory includes an understanding of living and dead matter: the center of atoms is filled with both living and dead electrons, and the dead electrons serve as food for the living ones.36 This living entity—this elemental unit of self-organizing matter—is, according to Platonov’s vocabulary, a “substance [veshchestvo] of existence.”

The Russian word veshchestvo can mean “matter,” “substance,” “thing,” “materiality,” or “stuff.” Robert Chandler, who has translated a number of Platonov’s works into English, often renders veshchestvo as “substance,” but also sometimes as “essence,” “thing,” or “object.” The root of the noun veshchestvo is veshch’, which means “thing.” Remember that Lissitzky titled his journal Veshch/Gegenstand/Objet. Maria Dmitrovskaia, a Russian researcher of Platonov, notes that the parallel usage of veshchestvo, veshch’, “matter,” and “body” corresponds to the archaic meaning in Old Medieval Russian, where veshch’ and veshchestvo sometimes were synonymous and where the understanding of a human body as veshchestvo was common. In archaic Russian, veshchestvo meant to be a material substratum of the world. It indicated things in existence and was a synonym of the word “material.” Such Platonov expressions as “metallic veshchestvo” and “fluid veshchestvo” were very common in eighteenth-century Russia.37

Veshchestvo is a reminder of veshch’; it is an elemental unit or an element of a decomposed psychophysical complex. In this sense veshchestvo is close to the English colloquial word “stuff,” or the German Stoff and Stofflichkeit. There is a scene in Platonov’s novel The Foundation Pit where the main character Voshchev collects “the objects [veshchi] of unhappiness and obscurity.”38 Thus, veshchestvo here appears as a memory of veshch’, as the remainder of its exhaustion in the past. It seems that this strange praxis of collecting the leaves, garbage, and destroyed objects of material culture exemplifies the act of recomposing and recollecting matter. In Bogdanov’s terminology, Voshchev is organizing life—the “veshchestvo of existence”—into complexes—veshchi. In Nikolai Fedorov’s terminology, he is collecting dead molecular pieces to resurrect the thinghood of a thing, the veshchnost’ veshchi, in the future. In 1931 Platonov writes:

The vulgar worldview [of materialism] anticipates that life is a combination of biological processes: “a human” properly is some sort of result of the relations and interactions of these forces—a human is relation. This is only half true. The other half is that the human is by itself veshchestvo, “materialism” included in bio-combinations. From here, and only from here—the human as by itself veshchestvo, and not only as relation—can one draw the great general conclusion that the door to the secret of nature is still open for humans. If, by contrast, a human is only “relation,” “combination,” etc., those doors are closed forever.39

For constructivism and productivism, forms of being emerge in the process of building and constructing the new. But for Platonov, the new already exists in the old, in the crumpled and poor form of veshchestvo. World-building is the resurrection of existing particles and elements, the restoration of a thing, the assembling of wandering senses, thoughts, and relations. The lowest entity—veshchestvo—corresponds to the molecular biology of self-organizing matter, but it produces the highest degree of organization: socially organized experience. Communism emerges out of the poverty of the elemental, out of the poor bodies of the proletariat. The laboring proletariat consists of those “who silently made useful veshchestvo” and those who signify not just a sociology of class relations, but also a restoration of the world in the process of communist world-building.40

Veshchestvo is a building material for the object and subject, the physical and the psychical composition of bodies, relations, and serial complexes of activities. It expresses degrees and logics of organization and structuring on the molecular, biological, and social levels. The constitutive unit of life is an element of experience in Bogdanov’s philosophy, and a veshchestvo of negative organizational spontaneity in Platonov. Taken together, the element of experience and veshchestvo introduce the principal role of the organizing force of being that shapes life-building. The Empirio-Marxist ontology of organization assumes the constructive and constitutive means of an art that not only changes, but also shapes forms of social being. Material culture as the organization of things, relations, and people replaces the concept of art.

The author thanks Danny Hayward for his help in editing this article.

Maria Chehonadskih is a philosopher and critic. She received PhD in philosophy from the Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy, Kingston University (London) in 2017. Chehonadskih works on the problem of Soviet epistemologies across Marxist philosophy, literature and art. She wrote a number of texts on Soviet philosophy, art theory and post-Soviet politics, and contributed to Radical Philosophy, South Atlantic Quarterly, Moscow Art Magazine and Alfabeta2. Chehonadskih occasionally curates and works in collaboration with artists. Her last exhibition ‘Shadow of a Doubt’ (curated together with Ilya Budraitskis) was dedicated to the problem of conspiracy (Moscow, 2014). Lives and works in London.

© 2018 e-flux and the author