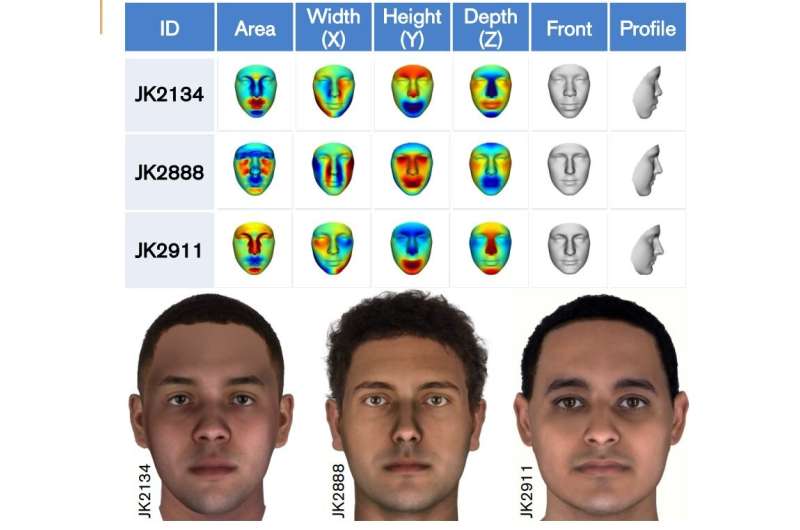

Faces of three ancient Egyptian mummies recreated using DNA technology and thermal meshing

A team of workers at Parabon Nanolabs has digitally recreated the faces of three mummies from ancient Egypt using DNA technology and thermal meshing. They have posted a release statement on the company's website describing their process and results.

The three mummies were found at a site in Egypt called Abusir el-Meleq, an ancient city located south of modern Cairo. Prior research has shown that they were buried sometime between 1380 BC and 425 AD. In 2017, researchers at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History found tissue that had survived in good enough condition to allow for genetic sequencing of the three bodies, all of whom were male. In this new effort, the workers have used data from that sequencing effort, along with other tools to digitally recreate the faces of the three mummies.

The process began with a type of phenotyping called Snapshot, which can be used to determine facial features, ancestry and skin color. It showed that all three of the mummies had once been young men with skin the color of modern Mediterranean or Middle Eastern people with deep brown eyes. They were also able to determine hair color and texture, freckling and facial shape. Next, the workers created 3D meshes using thermal scans of the mummies' heads. The meshes were then used to form the basic facial characteristics of the three young men (all three of whom were believed to be approximately 25 years old at the time of their death) based on their bone structure. The team then combined the data from their Snapshot phenotyping with their meshes to create digital images of the three men who lived thousands of years ago.

The workers note that there was severe degradation of the DNA, but point out that they did not need the full set of single nucleotide polymorphisms; all they needed were those that revealed information about certain traits that differ between individuals, such as eye and skin color. They note also that their techniques have also already been used to help identify the remains of people living in modern times as part of forensic efforts involved in cold cases.

Scans unveil secrets of world's oldest mummies

More information: parabon-nanolabs.com/news-even … rom-ancient-dna.html

© 2021 Science X Network

New approach to skeletal age-estimation can help identify juvenile remains

Peer-Reviewed PublicationIMAGE: DEANNA SMITH, AN SFU ARCHAEOLOGY MA STUDENT AND STUDY LEAD AUTHOR MEASURES A BONE IN THE LAB. view more

CREDIT: KOBIE HUANG

New research by SFU archaeologists could help forensic teams in their work to estimate the age of the remains of children discovered during archaeological work or in criminal investigative cases. Their study is published in the journal Forensic Science International.

While age is typically determined by dental records or other methods, such as measuring the long bones in the upper or lower limbs, those methods may not always be possible, especially in the case of young children. The researchers turned their attention to another approach—measuring the crania and mandibular bones, located in the skull.

For their study, researchers measured those bones in the child skeletal remains of known sex and age from natural history museum collections in Lisbon, Portugal and London, U.K. The bones were from 185 children from birth to 12.9 years who lived during the 1700s to 1900s. The measurements were found to provide a valid and comprehensive approach to juvenile age estimation.

According to SFU forensic anthropologist Hugo Cardoso, age, in combination with sex, context, and other characteristics of the skeleton, helps to narrow down who the child could be from a list of potential candidates. Families can then provide a DNA sample to confirm the identity of the child whose remains have been found, leading to closure for the family.

“Estimating the age of child remains is important because it helps with identification purposes, especially in criminal investigations,” says study lead Deanna Smith, an SFU archaeology MA student and member of the Wikwemikong First Nation. Determining the age of remains can help to reduce the pool of possibilities from a list of hundreds of missing children of various ages, for example.

Researchers assist in various situations where identification of remains is sought, from criminal investigations to cases with insufficient medical records to estimate age. “As physical anthropologists, we’re often called to identify found human remains, which then are subjected to a medicolegal death investigation,” says Cardoso, chair of the Department of Archaeology and co-director of the Centre for Forensic Research. “We are also involved in the study of remains found intentionally in archaeological projects, such as excavating a prehistoric or historic cemetery.”

Cardoso adds that in other archaeological contexts, excavating cemeteries can provide a snapshot of the entire population within a certain period of time and geographical area, allowing researchers to learn more about how people lived in the past—and age determination is a key factor. “Estimating age can help researchers to reconstruct demographics of the population and gain a better understanding of aspects of nutrition, health and stress during the growth years.”

###

JOURNAL

Forensic Science International

DOI

10.1016/j.forsciint.2021.110943

Extinction and origination patterns change

after mass extinctions

Extinction changes rules of body size evolution

Peer-Reviewed PublicationScientists at Stanford University have discovered a surprising pattern in how life reemerges from cataclysm. Research published Oct. 6 in Proceedings of the Royal Society B shows the usual rules of body size evolution change not only during mass extinction, but also during subsequent recovery.

Since the 1980s, evolutionary biologists have debated whether mass extinctions and the recoveries that follow them intensify the selection criteria of normal times – or fundamentally shift the set of traits that mark groups of species for destruction. The new study finds evidence for the latter in a sweeping analysis of marine fossils from most of the past half-billion years.

Whether and how evolutionary dynamics shift in the wake of global annihilation has “profound implications not only for understanding the origins of the modern biosphere but also for predicting the consequences of the current biodiversity crisis,” the authors write.

“Ultimately, we want to be able to look at the fossil record and use it to predict what will go extinct, and more importantly, what comes back,” said lead author Pedro Monarrez, a postdoctoral scholar in Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth). “When we look closely at 485 million years of extinctions and recoveries in the world’s oceans, there does appear to be a pattern in what comes back based on body size in some groups.”

Build back smaller?

The study builds on recent Stanford research that looked at body size and extinction risk among marine animals in groupings known as genera, one taxonomic level above species. That study found smaller-bodied genera on average are equally or more likely to than their larger relatives to go extinct.

The new study found this pattern holds true across 10 classes of marine animals for the long stretches of time between mass extinctions. But mass extinctions shake up the rules in unpredictable ways, with extinction risks becoming even greater for smaller genera in some classes, and larger genera losing out in others.

The results show smaller genera in a class known as crinoids – sometimes called sea lilies or fairy money – were substantially more likely to be wiped out during mass extinction events. In contrast, no detectable size differences between victims and survivors turned up during “background” intervals. Among trilobites, a diverse group distantly related to modern horseshoe crabs, the chances of extinction decreased very slightly with body size during background intervals – but increased about eightfold with each doubling of body length during mass extinction.

When they looked beyond the marine genera that died out to consider those that were the first of their kind, the authors found an even more dramatic shift in body size patterns before and after extinctions. During background times, newly evolved genera tend to be slightly larger than those that came before. During recovery from mass extinction, the pattern flips, and it becomes more common for originators in most classes to be tiny compared to holdover species who survived the cataclysm.

Gastropod genera including sea snails are among a few exceptions to the build-back-smaller pattern. Gastropod genera that originated during recovery intervals tended to be larger than the survivors of the preceding catastrophe. Nearly across the board, the authors write, “selectivity on body size is more pronounced, regardless of direction, during mass extinction events and their recovery intervals than during background times.”

Think of this as the biosphere’s version of choosing starters and benchwarmers based on height and weight more than skill after losing a big match. There may well be a logic to this game plan in the arc of evolution. “Our next challenge is to identify the reasons why so many originators after mass extinction are small,” said senior author Jonathan Payne, the Dorrell William Kirby Professor at Stanford Earth.

Scientists don’t yet know whether those reasons might relate to global environmental conditions, such as low oxygen levels or rising temperatures, or to factors related to interactions between organisms and their local surroundings, like food scarcity or a dearth of predators. According to Payne, “Identifying the causes of these patterns may help us not only to understand how our current world came to be but also to project the long-term evolutionary response to the current extinction crisis.”

Fossil data

This is the latest in a series of papers from Payne’s research group that harness statistical analyses and computer simulations to uncover evolutionary dynamics in body size data from marine fossil records. In 2015, the team recruited high school interns and undergraduates to help calculate the body size and volume of thousands of marine genera from photographs and illustrations. The resulting dataset included most fossil invertebrate animal genera known to science and was at least 10 times larger than any previous compilation of fossil animal body sizes.

The group has since expanded the dataset and plumbed it for patterns. Among other results, they’ve found that larger body size has become one of the biggest determinants of extinction risk for ocean animals for the first time in the history of life on Earth.

For the new study, Monarrez, Payne and co-author Noel Heim of Tufts University used body size data from marine fossil records to estimate the probability of extinction and origination as a function of body size across most of the past 485 million years. By pairing their body size data with occurrence records from the public Paleobiology Database, they were able to analyze 284,308 fossil occurrences for ocean animals belonging to 10,203 genera. “This dataset allowed us to document, in different groups of animals, how evolutionary patterns change when a mass extinction comes along,” said Payne.

Future recovery

Other paleontologists have observed that smaller-bodied animals become more common in the fossil record following mass extinctions – often calling it the “Lilliput Effect,” after the kingdom of tiny people in Jonathan Swift’s 18th-century novel Gulliver’s Travels.

Findings in the new study suggest animal physiology offers a plausible explanation for this pattern. The authors found the classic shrinking pattern in most classes of marine animals with low activity levels and slower metabolism. Species in these groups that first evolved right after a mass extinction tended to have smaller bodies than those that originated during background intervals. In contrast, when new species evolved in groups of more active marine animals with faster metabolism, they tended to have larger bodies in the wake of extinction and smaller bodies during normal times.

The results highlight mass extinction as a drama in two acts. “The extinction part changes the world by removing not just a lot of organisms or a lot of species, but by removing them in various selective patterns. Then, recovery isn’t just equal for everyone who survives. A new set of biases go into the recovery pattern,” Payne said. “It’s only by combining those two that you can really understand the world that we get five or 10 million years after an extinction event.”

Payne is also a professor of geological sciences and, by courtesy, of biology.

Support for this research was provided by the U.S. National Science Foundation and Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences.

METHOD OF RESEARCH

Data/statistical analysis

SUBJECT OF RESEARCH

Not applicable

ARTICLE TITLE

Mass extinctions alter extinction and origination dynamics with respect to body size

ARTICLE PUBLICATION DATE

6-Oct-2021