Sex and the Symbiont: Can Algae Hookups Help Corals Survive Climate Change?

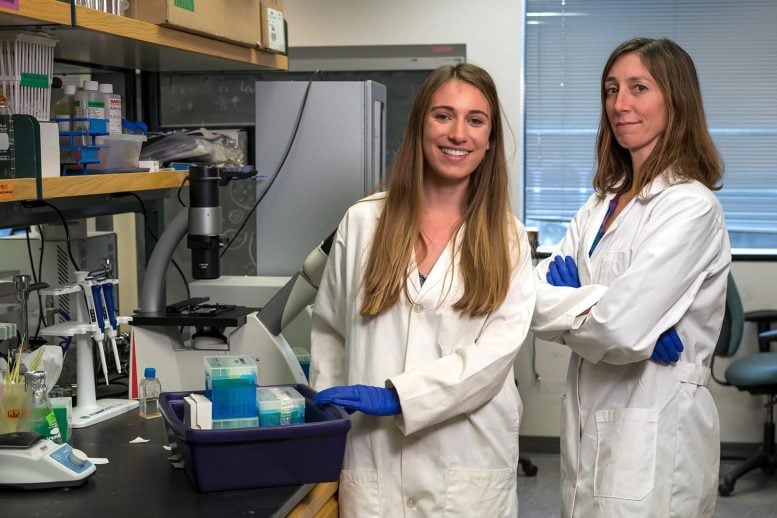

Rice University’s Lauren Howe-Kerr, left, and Adrienne Correa discovered that symbiont algae found on corals in French Polynesia are able to reproduce via mitosis and sex. That could make it easier to develop algae that better protect coral reefs from the effects of climate change. Credit: Brandon Martin/Rice University

Rice biologists’ discovery can be used to help climate-challenged reefs survive for now.

A little more sexy time for symbionts could help coral reefs survive the trials of climate change. And that, in turn, could help us all.

Researchers at Rice University and the Spanish Institute of Oceanography already knew the importance of algae known as dinoflagellates to the health of coral as the oceans warm, and have now confirmed the tiny creatures not only multiply by splitting in half, but can also reproduce through sex.

That, according to Rice marine biologist Adrienne Correa and graduate student Lauren Howe-Kerr, opens a path toward breeding strains of dinoflagellate symbionts that better serve their coral partners.

Dinoflagellates not only contribute to the stunning color schemes of corals, but critically, they also help feed their hosts by converting sunlight into food.

“Most stony corals cannot survive without their symbionts,” Howe-Kerr said, “and these symbionts have the potential to help corals respond to climate change. These dinoflagellates have generation times of a couple months, while corals might only reproduce once a year.

“So if we can get the symbionts to adapt to new environmental conditions more quickly, they might be able to help the corals survive high temperatures as well, while we all tackle climate change.”

In an open-access study in Nature’s Scientific Reports, they wrote the discovery “sets the stage for investigating environmental triggers” of symbiont sexuality “and can accelerate the assisted evolution of a key coral symbiont in order to combat reef degradation.”

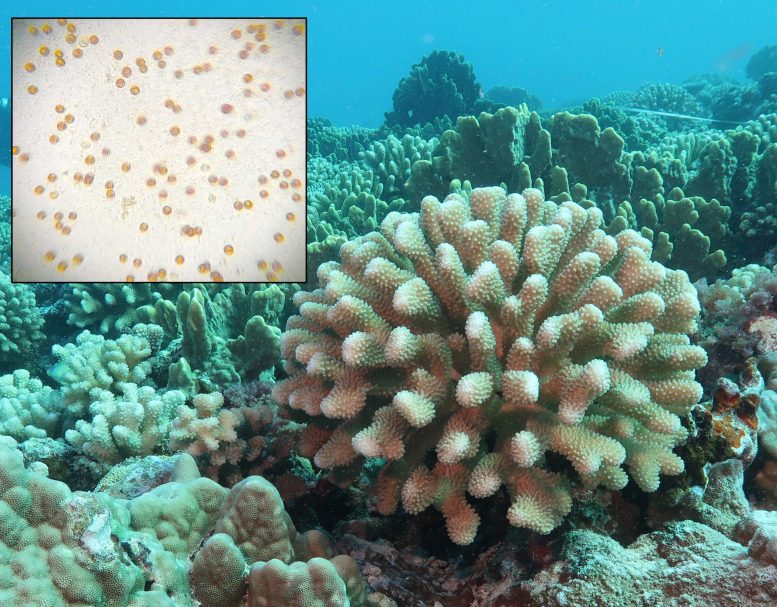

A coral of the type studied by scientists at Rice University is protected by dinoflagellates (inset), algae that turn sunlight into food to feed and protect reefs. The study showed the algae are able to reproduce via sex, opening a path toward accelerated evolution of strains that can better protect coral from the effects of climate change. Credit: Inset by Carsten Grupstra/Rice University; coral image by Andrew Thurber/Oregon State University

To better understand the algae, the Rice researchers reached out to Rosa Figueroa, a researcher at the Spanish Institute of Oceanography who studies the life cycles of dinoflagellates and is lead author on the study.

“We taught her about the coral-algae system and she taught us about sex in other dinoflagellates, and we formed a collaboration to see if we could detect symbiont sex on reefs,” Howe-Kerr said.

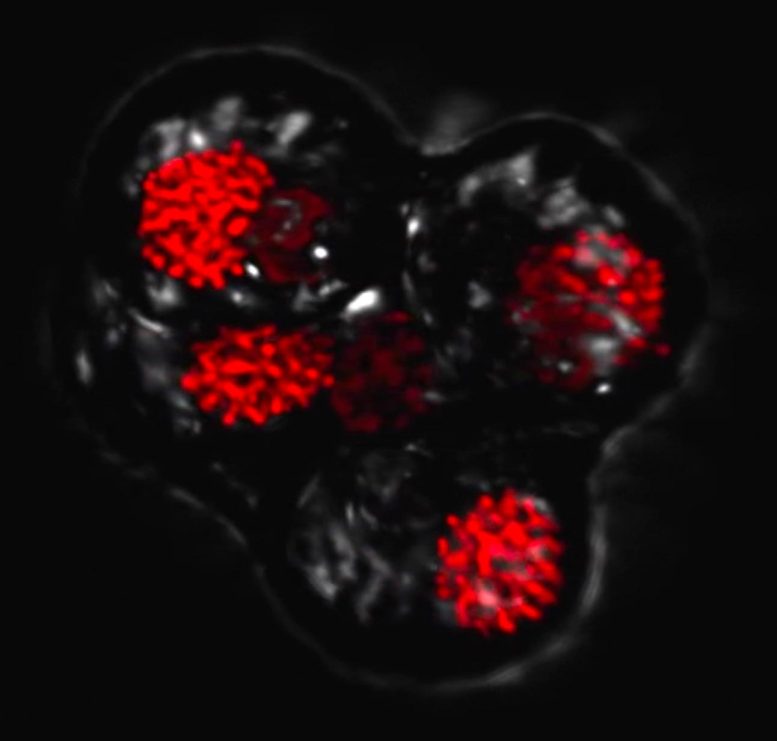

“In genomic datasets of coral dinoflagellates, researchers would see all the genes coral symbionts should need to reproduce sexually, but no one had been able to see the actual cells in the process,” said Correa, an assistant professor of biosciences. “That’s what we got this time.”

The discovery follows sampling at coral reefs in Mo’orea, French Polynesia, in July 2019 and then observation of the algae through advanced confocal microscopes that allow for better viewing of three-dimensional structures.

A dinoflagellate tetrad cell that will soon split into four separate cells, captured by Rice University scientists through a confocal microscope. The cell’s four nuclei are depicted in red. Researchers at Rice and in Spain determined from experiments that these symbionts, taken from a coral colony in Mo’orea, French Polynesia, are able to reproduce both through mitosis and via sex. Credit: Correa Lab/Rice University

“This is the first proof that these symbionts, when they’re sequestered in coral cells, reproduce sexually, and we’re excited because this opens the door to finding out what conditions might promote sex and how we can induce it,” Howe-Kerr said. “We want to know how we can leverage that knowledge to create more genetic variation.”

“Because the offspring of dividing algae only inherit DNA from their one parent cell, they are, essentially, clones that don’t generally add to the diversity of a colony. But offspring from sex get DNA from two parents, which allows for more rapid genetic adaptation,” Correa said.

Symbiont populations that become more tolerant of environmental stress through evolution would be of direct benefit to coral, which protect coastlines from both storms and their associated runoff.

“These efforts are ongoing to try to breed corals, symbionts and any other partners to make the most stress-resistant colonies possible,” Correa said. “For coral symbionts, that means growing them under stressful conditions like high temperatures and then propagating the ones that manage to survive.

“After successive generations we’ll select out anything that can’t tolerate these temperatures,” she said. “And now that we can see there’s sex, we can do lots of other experiments to learn what combination of conditions will make sex happen more often in cells. That will produce symbionts with new combinations of genes, and some of those combinations will hopefully correspond to thermotolerance or other traits we want. Then we can seed babies of the coral species that host that symbiont diversity and use those colonies to restore reefs.”

Reference: “Direct evidence of sex and a hypothesis about meiosis in Symbiodiniaceae” by R. I. Figueroa, L. I. Howe-Kerr and A. M. S. Correa, 22 September 2021, Scientific Reports.

DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-98148-9

The research was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and the European Community Project (DIANAS-CTM2017-86066-R), a Lewis and Clark Grant from the American Philosophical Society, a Wagoner Foreign Study Scholarship, the National Science Foundation (1635798) and an early-career research fellowship from the Gulf Research Program of the National Academy of Sciences (2000009651).