Severe Drought in Sacramento Valley Slams Farmers, Salmon and Migratory Birds

The drought has stunted grasses that Josh Davy's cattle usually feed on, so he prepares hay for them at his ranch near Red Bluff. (Miguel Gutierrez Jr./CalMatters)

Rachel Becker

CALMATTERS

May 26,2022

LONG READ

Standing on the grassy plateau where water is piped onto his property, Josh Davy wished his feet were wet and his irrigation ditch full.

Three years ago, when he sank everything he had into 66 acres of irrigated pasture in Shasta County, Davy thought he’d drought-proofed his cattle operation.

He’d been banking on the Sacramento Valley’s water supply, which was guaranteed even during the deepest of droughts almost 60 years ago, when irrigation districts up and down the valley cut a deal with the federal government. Buying this land was his insurance against droughts expected to intensify with climate change.

But this spring, for the first time ever, no water is flowing through his pipes and canals or those of his neighbors: The district won’t be delivering any water to Davy or any of its roughly 800 other customers.

'Without the water, we have dirt. It's basically worthless.'

Mathew Garcia, rice farmer, Glenn County

Without rain for rangeland grass where his cows forage in the winter, or water to irrigate his pasture, he will probably have to sell at least half the cows he’s raised for breeding and sell all his calves a season early. Davy expects to lose money this year — more than $120,000, he guesses, and if it happens again next year, he won’t be able to pay his bills.

“I would never have bought [this land] if I had known it wasn’t going to get water. Not when you pay the price you pay for it,” he said. “If this is a one-time fluke, I’ll suck it up and be fine. But I don’t have another year in me.”

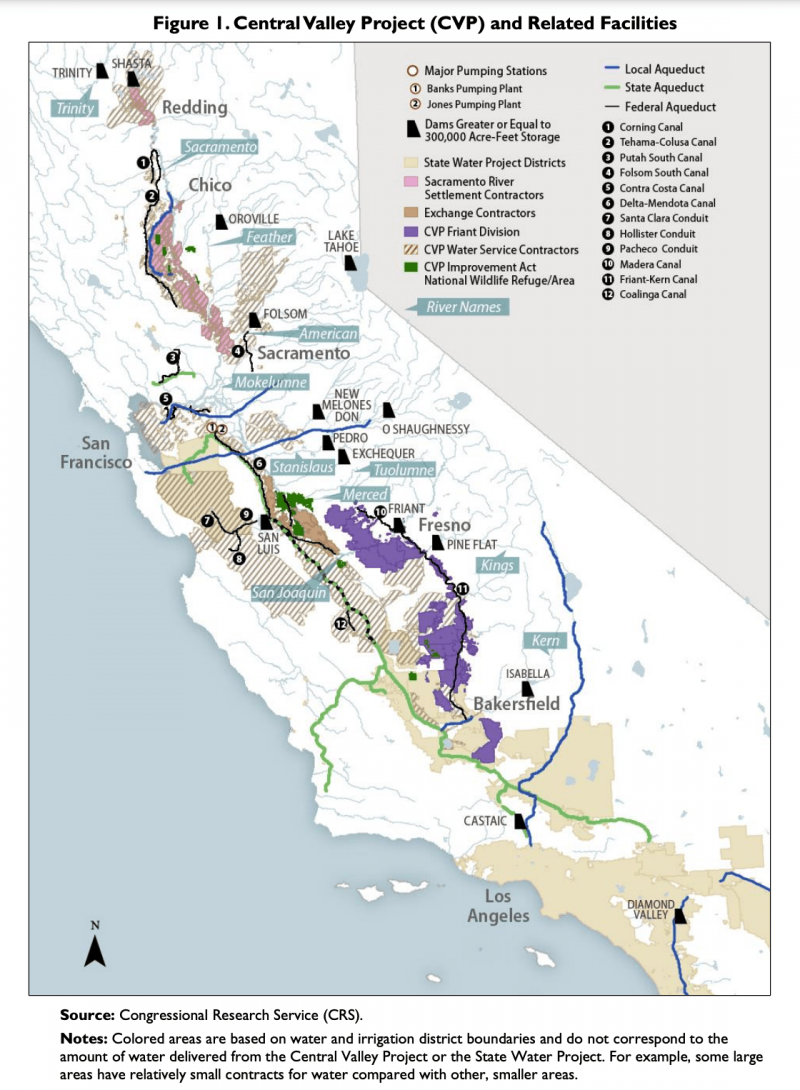

Since 1964, the water supply of the western Sacramento Valley has been virtually guaranteed, even during critically dry years, the result of an arcane water rights system and legal agreements underlying operations of the Central Valley Project, the federal government’s massive water management system.

But as California weathers a third year of drought, conditions have grown so dry and reservoirs gotten so low that the valley’s landowners and irrigation districts are being forced to give up more water than ever before. Now, this region, which has relied on the largest portion of federally managed water flowing from Lake Shasta, is wrestling with what to do as its deal with the federal government no longer protects them.

An irrigation canal on Davy’s pasture in Shasta County is bone-dry on April 27, 2022. (Miguel Gutierrez Jr./CalMatters)

All relying on the lake’s supplies will make sacrifices: Many are struggling to keep their cattle and crops. Refuges for wildlife also will have to cope with less water from Lake Shasta, endangering migratory birds. And the eggs of endangered salmon that depend on cold water released from Shasta Dam are expected to die by the millions.

For decades, water wars have pitted growers and ranchers against nature, north against south. But in this new California, where everyone is suffering, no one is guaranteed anything.

“In the end, when one person wins, everybody loses,” Davy said. “And we don’t actually solve the problem.”

Portioning out the river's precious water

This parched valley was once a land of floods, regularly inundated when the Sacramento River overflowed to turn grasslands and riverbank forests into a vast, seasonal lake.

Colonizers who flooded into California on the tide of the Gold Rush of 1849 staked their claims to the river’s flow with notices posted to trees in a system of “first in time, first in right.”

The river was corralled by levees, the region replumbed with drainage ditches and irrigation canals. Grasslands and swamps lush with tules turned to ranches and wheat fields, then to orchards, irrigated pasture and rice.

The federal government took over in the 1930s, when it began building the Central Valley Project’s Shasta Dam, which displaced the Winnemem Wintu people. A 20-year negotiation between water rights holders — the colonizers, who comprised miners, landowners and irrigation districts — and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation culminated in a deal in 1964.

Today, under the agreements, which were renewed in 2005, nearly 150 landowners and irrigation districts that supply almost half a million acres of agriculture in the western Sacramento Valley are entitled to receive about three times more water than Los Angeles and San Francisco use in a year.

It’s a controversial amount in the parched state. Before this year, the Sacramento River Settlement Contractors, as they’re called, received the largest portion of the federally managed supply of water that flows from Shasta Lake. It’s more than cities receive, more than wildlife refuges, more even than other powerful agricultural suppliers like the Westlands Water District farther south.

Their contract bars the irrigation districts’ supply from being cut by more than a quarter in critically dry years. During the last drought in 2014, federal efforts to cut it to 40% of the contracted amount were met with resistance, and deliveries ultimately increased to the full 75% allocation for the dry year.

But this year, facing exceptionally dry conditions, the irrigation districts negotiated with state and federal agencies, and agreed in March to reduce their water deliveries to 18%. Other agricultural suppliers with less senior rights are set to get nothing.

Growers understand that they have to sacrifice some water this year, said Thaddeus Bettner, general manager for Glenn-Colusa Irrigation District, the largest of the Sacramento River Settlement Contractors and one of the largest irrigation districts in the state. But he wondered why irrigation districts in the western Sacramento Valley draw so much of the blame.

“I understand we’re bigger than everybody so we catch the focus,” Bettner said. “We’re just trying to survive this year. Frankly, it’s just complete devastation up here. And it’s unfortunate that the view seems to be that we should get hurt even more to save fish.”

Cutting deliveries to growers means that more water can flow through the rivers, which slightly raises the chances for more endangered winter-run Chinook salmon to survive this year.

“They had the water rights to take 75% of their allocation instead of 18%, and we were anticipating another total bust,” said Howard Brown, senior policy advisor with NOAA Fisheries’ West Coast Region. “One hundred percent temperature-dependent mortality [of salmon eggs] would not have been something out of reason to imagine.”

Yet more than half the eggs of endangered winter-run Chinook salmon are expected to die this year, according to the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Low water levels at Shasta Lake on April 25, 2022. (Miguel Gutierrez Jr./CalMatters)

State and federal biologists are racing to move some of the adult salmon to a cooler tributary of the Sacramento River and a hatchery.

“We’re spreading the risk around, and putting our eggs in different baskets,” Brown said. “The animal that’s on the flag of California is extinct. How many can we afford to lose before we lose our identity as people and as citizens of California?”

'Nothing like I thought I'd ever see' in the Sacramento Valley

In any other year, Davy would run his cattle on rain-fed rangeland he leases in Tehama County until late spring before moving the herd to his home pasture, kept green and lush with spring and summer irrigation.

Davy, who grew up roping and running cattle, supports his career as a full-time rancher with his other full-time job as a farm adviser with the University of California Cooperative Extension, specializing in livestock, rangelands and natural resources.

Three years ago, he sold his home in Cottonwood, on the Shasta-Tehama county line, for a fixer-upper nearby with holes in the floor, a shoddy electrical system and windows that wouldn’t close. This fixer-upper had two inarguable selling points: a view of Mount Shasta, and water from the Anderson-Cottonwood Irrigation District, a settlement contractor.

This year, without rain, the grass where his cows forage through the winter crunches underfoot.

“This grass should be up to my waist right now,” Davy said, readying a chute he would soon use to transport his cattle. He unloaded hay from his pickup to feed the cows and calves until he could move them — unheard of, he said, in April.

Cattle feed on hay in Tehama County. (Miguel Gutierrez Jr./CalMatters)

Forty miles away, his pasture, green from the April rains, is faring a little better — but the green can’t last without irrigation. Thinking about it too hard makes Davy feel sick.

“I try to stick to what I can get done today, and then assume next year I’ll be OK. I think that’s the mantra for agriculture: Next year will be better,” he said.

About 75 miles south of Davy’s ranch, rangeland and irrigated pastures open up to orchards and thousands of acres of empty rice fields.

“Nothing like I thought I’d ever see,” said Mathew Garcia, gazing at one of his dry rice fields in Glenn, about an hour and a half north of Sacramento.

In any other year, he would have been preparing to seed and flood the crumbled clay. This year, he had to abandon even the one field he’d planned to irrigate from a well; the ground was too thirsty to hold the water.

Garcia’s water comes from two different irrigation districts with settlement contracts. This year, the roughly 420 acres he farms will see water deliveries either eliminated or too diminished to plant rice. He’ll funnel the water instead to his tenant’s irrigated pasture where cattle graze.

“Without the water, we have dirt. It’s basically worthless,” Garcia said. “It’s very depressing.”

California is one of the main rice producers in the United States, and almost all is grown in the Sacramento Valley. It’s an especially water-demanding crop: The plants and evaporation drink up about two-thirds of the flows; the rest dribbles through the earth to refill groundwater stores or flows back into irrigation ditches that supply other crops, rivers and wetlands.

Garcia places some of the blame on the weather. But he also blames federal regulators, who allow water to flow from the reservoirs year-round for fish, wildlife and water quality.

“Everybody says, well, you shouldn’t farm in the desert. Does this look like a desert to you? No. It looks like fertile, beautiful farmland with the most amazing irrigation system that’s ever been put in. And they’re just taking the water from it. They’re creating a desert,” Garcia said

.

Mathew Garcia, standing in one of his fallow rice fields in Glenn, says he can't plant anything this year because of reduced water deliveries. (Miguel Gutierrez Jr./CalMatters)

In the depths of California’s last historic drought from 2012 through 2016, Garcia could still plant his fields. Even with last year’s reduced water deliveries, he planted — filling the gaps in water supply by pumping from his groundwater wells.

Garcia will survive this year: He credits his wife’s foresight to purchase crop insurance years ago. Without it, he said, he’d be done — he’d have to sell land, maybe find another job.

“If this drought sustains, I don’t know how long insurance is going to last. And then at what point do you throw in the towel?” said Garcia. “There’s a teetering point somewhere. Everybody’s is different. I don’t know where mine is yet.”

Local water suppliers anticipate that about 370,000 acres of cropland will go fallow in the western Sacramento Valley, the result of diminished deliveries to the settlement contractors. Most of those acres lie in Colusa and Glenn counties, where agriculture is the epicenter of the economy. Money and jobs radiate from the fields to the crop dusters and chemical suppliers, rice driers and warehouses.

And, like the water, jobs for farmworkers have dried up.

For nine years, Sergio Cortez has been traveling from Jalisco, Mexico, to work in Sacramento Valley fields. This is the driest he’s ever seen it, and he knows that next year could be worse.

“Aquí el agua es todo, pues,” he said. “Al no haber agua, pues no hay trabajo.” Water is everything, he said. If there’s no water, there’s no work.

The parking lot at the migrant farmworker housing in Colusa County where Cortez and his family live for part of the year was full of cars and pickups that would normally be parked at the fields. Cortez hadn’t worked in two days.

For Adolfo Morales Martinez, 74, it had been a month since he worked. And, at the end of April, his unemployment benefits were about to end.

“Desesperados. Estamos desesperados,” he said. “Pues en el campo gana uno poquito, no? Y sin nada? No mas.” We’re desperate, he said. In the fields, he can earn a little. But now, nothing.

Normally Morales Martinez drives a tractor, readying rice fields for planting. Now it’s like a desert, his wife, Alma Galavez, said.

“Eso está desértico, vea. Todo. Nada, nada. Está feo y triste,” she said. There’s nothing. It’s ugly and sad.

Extreme effects on salmon and birds, too

Environmental advocates and California tribes have been fighting the growers’ and irrigation districts’ claim to California’s finite water supply for years, citing inadequate water to maintain water quality and temperatures for endangered fish and the Sacramento Delta.

“People who have built their farms in the desert, or in areas where their water has to be exported to them, need to think about changing. Because that’s what’s killing the state,” said Caleen Sisk, chief and spiritual leader of the Winnemem Wintu Tribe, whose lands were flooded with the damming of Lake Shasta.

To Sisk, the salmon that once spawned in the tributaries above the Central Valley signal the region’s health. “If there are no salmon, there will be no people soon,” she said.

Federal scientists estimate that last year about three-quarters of endangered winter-run Chinook salmon eggs died because the water downstream of a depleted Lake Shasta was too warm. Only about 3% of the salmon ultimately survived to migrate downriver.

“It’s been clear for decades that there was a need to reduce diversions,” said Doug Obegi, senior attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council. “The consequences are just becoming more and more extreme.”

In 2020, California sued the Trump administration over what it said were flawed federal assessments for how the Central Valley Project’s operations harm endangered species.

The judge sent the federal plans back for more work and approved what he called a “reasonable interim approach“ that called for prioritizing fish and public safety over irrigation districts. He called the contracts an “800-pound gorilla” and said they “make it exceedingly and increasingly difficult” for the federal government to be “sufficiently protective of winter-run [salmon].”

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation spokesperson Gary Pitzer said the agency worked with the districts to reach an agreement on how much water to deliver because “it’s the right thing to do, particularly during drought — one of the worst on record.”

Environmental advocacy groups applauded the reduced allocations to the Sacramento Valley irrigation districts. But they also raised concerns that other irrigation districts with similar contracts elsewhere in the state would still see their full dry-year allocations, and cautioned that the temperatures will still kill salmon by the scores this year.

Wildlife refuges where birds can rest and eat during their 4,000-mile winter journeys along the Pacific Flyway also are receiving significantly less water this year.

Curtis McCasland, manager of the Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge Complex, expects less than half a typical year’s water supply to be delivered to the refuges this year — cobbled together from purchased water supplies, federal deliveries and, he hopes, storm flows this winter.

North of Sacramento, the five refuges in the complex are painstakingly tended wilderness in a sea of agriculture. More than a century ago, wetlands fanned out for miles on either side of the flood-prone Sacramento River. Now, more than 90% of the state’s wetlands are gone, drained for fields, homes and businesses. Those remaining in these refuges now depend on water flowing from Shasta Dam and shunted through irrigation canals.

At the end of April, the Colusa National Wildlife Refuge offered an oasis among the barren rice fields, which normally provide about two-thirds of the migrating bird’s calories. Dark green bulrushes rose from shallow ponds where shorebirds jackhammered their bills in and out of the muck.

An American bittern feeds at the Colusa National Wildlife Refuge

on April 28, 2022. (Miguel Gutierrez Jr./CalMatters)

McCasland knows all this lush green can’t last. As he steered an SUV past black-necked stilts picking their way through the water and ducklings paddling ferociously, he talked of bracing for another dry year.

“Instead of being those postage stamps in a sea of rice, we’re going to be postage stamps in a sea of fallow fields,” McCasland said.

In a typical year, the refuge wetlands that depend on federal water get much less water than the settlement contractors are entitled to — about 4% of the total, McCasland estimates. And he worries that this year, whatever water they do receive won’t be enough to keep all these birds fed and healthy.

More than a million birds descend on the refuges every winter to rest and find food. More stop in the surrounding rice fields, which are largely dry this year.

“In years where Shasta is at a normal or average level, it should be no problem to get us the water,” he said. “In years like this, certainly it’s going to be terribly difficult.”

The drought may already have taken a toll. Last November, only 745,000 birds landed in the refuge, a decrease of more than 700,000 from November of 2019, although some may have remained farther north because of unseasonably balmy weather there.

The refuges are like a farm, where McCasland and his colleagues carefully cultivate tule, shrubs and grasses with pulses of summertime irrigations. With less water this summer, these wintertime food sources for birds will dry and shrivel. And with less water during the peak of fall and winter migrations, hungry birds will be packed together in the few remaining marshes — raising the risk of outbreaks from diseases like avian botulism or cholera.

“There’s not a lot of places for these birds to go,” McCasland said. “The Sacramento Valley has always been the bankable piece. ... They do have wings, they may be able to move through.” But, he added, “the question is, what happens next?”

CalMatters Photo Editor Miguel Gutierrez contributed to this story.

.jpg)

.jpg)