PA Reporter

Thu, December 8, 2022

Levelling Up Secretary Michael Gove has granted planning permission for what would be the first new coal mine in 30 years but why is it so controversial?

– What is the proposal?

West Cumbria Mining (WCM) plans to open a deep coal mine on the former Marchon chemical works on the outskirts of Whitehaven, Cumbria, to mine metallurgical or coking coal for use in the steel industry.

The mine’s application says that nearly 2.8 million tonnes of coal will be extracted per year.

(PA Graphics)

– How long has it taken to get approval?

The development was first proposed in 2017 and has been approved three times by Cumbria County Council but then-communities secretary Robert Jenrick decided to “call in” the application so that an inquiry could be held to explore the arguments put forward by both supporters and opponents of the proposal. The decision was repeatedly delayed following the inquiry last year.

– How many jobs will it provide?

The inquiry heard the mine would provide 532 permanent jobs, 80% filled from the local workforce, and support 1,000 jobs in the supply chain.

– Why is it so controversial?

A little over a year ago the UK hosted the Cop26 climate summit in Glasgow, where it lobbied other countries to “consign coal to history”.

Opponents say the decision undermines UK efforts to reach net zero and sends the wrong signals to other countries about its climate priorities.

Labour shadow climate secretary Ed Miliband said it is “no solution to the energy crisis, it does not offer secure, long-term jobs, and it marks this Government giving up on all pretence of climate leadership”.

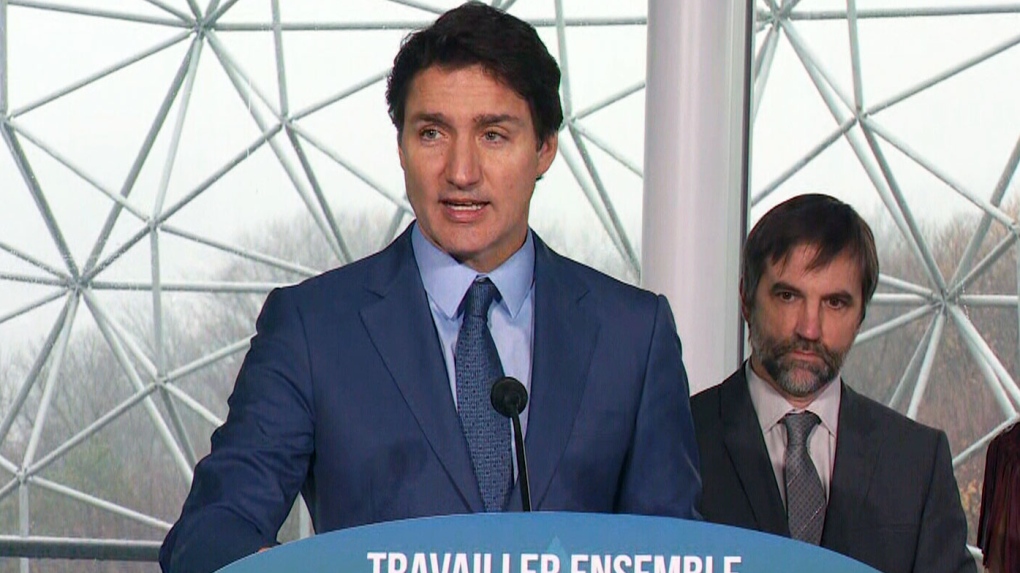

Demonstrators outside the proposed Woodhouse Colliery, south of Whitehaven

Gregory Jones KC, representing WCM at last year’s inquiry, claimed the development would be a world first in being a “net zero compliant” mine and help in the “transition” to a greener steel industry.

But WCM’s case was described as all “smoke and mirrors” by Estelle Dehon, representing South Lakes Action on Climate Change (SLACC).

Ms Dehon said a “myth has been spun” that local mined coal would be used in the UK only, instead of importing US coal, as the raw material could be exported across the world and the “magic of mitigation” and off-setting did not exist in reality.

– What do supporters say?

Those who have welcomed the decision say the mine will create jobs and opportunity in the area.

Mike Starkie, Conservative mayor of Copeland in Cumbria, said “the biggest announcement in generations” will “bring jobs, prospects and opportunity to the people of west Cumbria and the people of west Cumbria are going to be grateful for generations”.

The Observer view on the indefensible decision to open a deep coalmine in a climate crisis

Observer editorial

The government says the needs of UK steelmaking override the environmental impact. The industry thinks differently

The decision to approve a new £165m coalmine in Cumbria reveals an unpleasant truth about the government. It demonstrates, with brutal clarity, that No 10 has no credible green agenda and does not understand or care about the climatic peril our world is facing.

Ministers are clearly focused only on short-term, tactical gain – in this case, to give a brief boost to local employment – at the expense of forming a strategy for reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050 and maintaining world leadership in the battle to limit the impact of greenhouse gas emissions on our climate.

Lord Deben, chair of the Climate Change Committee, the government’s independent adviser, has described the decision to approve the colliery – to be built by West Cumbria Mining – as “absolutely indefensible”. The former Conservative minister is quite correct in this analysis, which, in line with other experts, flatly contradicts the levelling up secretary Michael Gove’s arguments for approving the mine at Woodhouse near Whitehaven.

The government claims that the Woodhouse colliery, the first deep coalmine to be approved for 30 years, will produce coking coal that is desperately needed for steelmaking in Britain and is therefore vital for UK industry as a whole. This is untrue. For one thing, British steelmakers will be legally required – as part of our climate obligations – to move to low-carbon production in the next 13 years. When that happens it will no longer be able to use coking coal. Output from Woodhouse colliery therefore has no long-term future in Britain.

Approval of this coalmine … confirms that the government’s protestations in favour of a green economy are a shamPaul Ekins, UCL Institute for Sustainable Resources

In any case, the coal that will be dug up at the mine will have a high sulphur content. Many UK steelmakers have indicated that this makes it unacceptable from the start; two companies have already rejected any prospect of ever burning Woodhouse coal. Thus its short-term use in the UK also looks limited, with only one of the current four blast furnaces expected to exploit its coal. As a result, industry figures and energy experts predict that around 90% of Woodhouse’s coal will be exported – to a world that already has a glut of fossil fuels. Steelmaking in Europe is also changing and will rely on hydrogen, not coal, in the near future – leaving Britain to seek markets for its Cumbrian coal in places where environmental constraints are limited. In the process, we will have become a supplier of dirty fuel to the planet.

Approval of the colliery seriously tarnishes the UK’s reputation as a global leader on climate action and opens us up to well-justified charges of hypocrisy. Telling other countries to ditch coal while creating new mines will seriously undermine British negotiators’ chances of influencing climate summits. India and other developing nations will certainly not be happy to be told to avoid using fossil fuels by a country that is exploiting new sources of the most polluting of all hydrocarbons.

It is a grim, unsettling, shameful situation that was summed up by Professor Paul Ekins, of the Institute for Sustainable Resources at University College London, last week: “Actions speak louder than words, and approval of this coalmine, instead of seeking investment in renewable energy on the same site, confirms that the government’s protestations in favour of a green economy are a sham.”

Scientists estimate that the colliery will lead to the release of 250m tonnes of carbon dioxide over the next 30 years. West Cumbria Mining says it will create around 500 jobs. In an overheating world, which will become increasingly intolerant of fossil fuels, these jobs are going to be short lived.

Could Cumbria coalmine be stopped despite government green light?

Mine could affect Britain’s climate commitments, which some believe could help get decision struck down

Fiona Harvey

The government has given the green light to a new coalmine in Cumbria, the first in the UK for more than 30 years, but already moves have begun to challenge the decision before construction work can start.

Climate campaigners are examining the decision with a view to a legal challenge, based on the UK’s national and international legally binding climate commitments.

The Guardian understands that lawyers working for NGOs will be looking for grounds to bring a high court claim against the planning permission. If such a claim were to succeed, the court could strike down the government’s decision and send it back to ministers to redetermine.

Tony Bosworth, an energy campaigner at Friends of the Earth, said: “The evidence against this mine is huge. It will have a significant impact on UK climate targets, while the market for coal is already disappearing. The UK steel industry wants to move to greener production, like its counterparts in mainland Europe who are rapidly moving away from coal.”

Another threat to the mine’s future is the general election that must take place within the next two years. Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the Green party have all made clear their opposition to the new mine.

Caroline Lucas, Green Party MP for Brighton Pavilion, vowed to keep fighting: “This government has backed a climate-busting, backward-looking, business-wrecking, stranded asset coalmine. This mine is a climate crime against humanity – and such a reckless desire to dig up our dirty fossil fuel past will be challenged every step of the way.”

Protesters are also gearing up to take local action at the site of the mine, and any banks and investors that finance the mine will also be put under pressure in public campaigns.

All of this means that it is possible that the new mine will never be operational. The economic viability of the mine – which will cost £165m, create 500 new jobs and produce an estimated 2.8m tonnes of coking coal a year, for steel-making – is already in doubt. Two UK steel companies have said they will not need its coal, and most leading European steel-makers are adopting green production methods.

Ron Deelan, a former chief executive of British Steel, said: “This is a completely unnecessary step for the British steel industry, which is not waiting for more coal as there is enough on the free market available. The British steel industry needs green investment in electric arc furnaces and hydrogen to protect jobs and make the UK competitive.”

The UK’s own steel industry must reach net zero emissions by 2035, according to the government’s independent statutory advisers on climate, the Committee on Climate Change.

Philip Dunne, the Tory MP who is chair of the environmental audit committee in parliament, said: “Coal is the most polluting energy source, and is not consistent with the government’s net zero ambitions. It is not clear cut to suggest that having a coalmine producing coking coal for steelmaking on our doorstep will reduce steelmakers’ demand for imported coal. On the contrary, when our committee heard from steelmakers earlier this year, they argued that they have survived long enough without UK domestic coking coal and that any purchase of coking coal would be a commercial decision.”

For these reasons, about 83% of the coal produced is likely to be for export, but who the customers may be remains unknown. Steel produced using coal may soon face penalties in the EU, where moves are under way to bring in “carbon border adjustment mechanisms” (CBAMs), which operate as tariffs on high-carbon, favouring lower-carbon products instead, such as steel made with renewable energy.

Simon Nicholas, energy finance analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, said: “The decision comes as the UK steel sector calls for government support to transition to low-carbon technology, in a bid to remain competitive with the European steel industry, which has seen an acceleration in its technology transition away from coal in 2022.”

Supporters of the mine point to the 500 to 530 jobs that are likely to be created. But environmental experts said many more jobs were likely in green industries in future, such as windfarms, solar farms, replacing gas for heating with district heating networks and heat pumps, and tree-planting and nature conservation.

Rebecca Willis, professor in energy and climate governance at the University of Lancaster, said: “There is no business case or scientific justification for this mine, which has only been made possible by a quirk of our planning laws. It will harm the UK’s climate credentials and do very little for communities in Cumbria, where the focus should be on delivering long-term, secure and green jobs.”

Reaction from climate campaigners in developing countries, which have for years been urged by the UK to move away from coal, has also been critical.

Steve Maël Size, of the Care For Environment/CAN group in Cameroon, pointed out that the UK had made coal a key issue in its presidency of the Cop26 climate summit in Glasgow last year. “If a power like the UK, which was among the pioneers in the fight against coal, decides to reinvest to open [a coalmine], that would mean that it has long fought for nothing,” he said.

Northern spotted owls, which in Canada live only in old-growth forests in southwest B.C., are critically endangered. Photo: Province of British Columbia /

Northern spotted owls, which in Canada live only in old-growth forests in southwest B.C., are critically endangered. Photo: Province of British Columbia /