Once again the Greek ferry system has attracted international attention for the abnormal and poor operational standards that have become a “custom of the trade.” The master of a ro/pax ferry who saved his ship, passengers and crew from an imminent grounding has not been applauded, but has instead been arrested, fired and ridiculed. Is he a criminal or a hero?

Scapegoats have been a convenient solution to cover the systematic malfunctions that have prevailed for years in the Greek Islands ferry scene, and masters are the stars of this unacceptable standard. The master of the ferry Saonisos acted prudently and pushed away from the pier when gusty side winds hit his vessel during a “touch-and-go” Med mooring maneuver, exactly as vessels have done every day in the Aegean for decades. Unfortunately for him, bystanders with mobile phones captured the scene, and he has been treated as a criminal for doing what he was trained and expected to do - save his ship from an imminent hard grounding.

Why did this occur, and how did we get in this point? Let’s have a look at the history of how the Greek ferry scene developed its current practices.

The Aegean Sea counts numerous islands that have long been connected with the mainland by ferries, and in recent decades a ro/pax ferry system has been developed to serve the increasing development of these islands. Vessel quality, size and service have all improved, but port facilities – which are a key component of the system – have not.

Figure 1: The Fast Ferries Andros in an emergency abort maneuver to avoid a breakwater grounding in Gavrio Port. Courtesy www.enandro.gr

The region’s underdeveloped port facilities are totally disproportional to current vessel size and traffic volume. Therefore, the only solution for fitting bigger and bigger vessels into tiny ports was the development of the master’s and the crew’s skill. The use of the Med mooring technique for a rapid “touch-and-go” turnaround was honed and advanced under siginificant commercial pressure, and evolved into a standard operational procedure serving countless passengers and vehicles yearly, despite the constant adverse weather conditions of the Aegean.

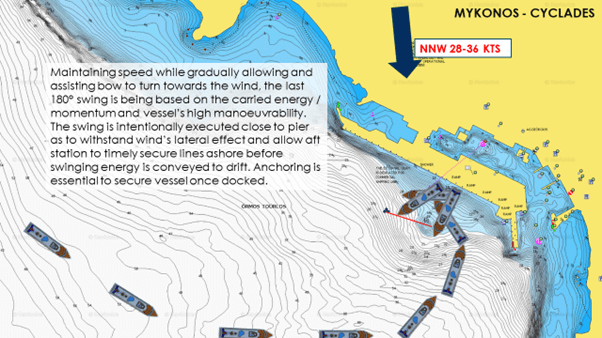

The Med mooring technique mostly used by ro/pax ferries, and the docking occurs with simultaneous use of anchors, aft mooring lines and a lowered ramp, which acts as a ‘brake’ due to its weight. While in the past the vessel was secured with numerous mooring lines, in a ferry system where sequential port calls are planned and executed in a 15-20 minute timeframe, the Med mooring technique has time saving advantages.

Figure 2: A standard Med mooring maneuver in Mykonos using anchor and mooring lines with stern ramp. Courtesy of the author

Under pressure to serve the islands, many of which have turned to tourist destinations, the current ferry system developed and established itself. While not rigidly safe as seen from international maritime carriage terms and standards, it is statistically decent, and it has allowed companies to develop, islanders and visitors to move, and masters and crewmembers to make their living.

Andros Port is only two hours by ferry from Rafina, the second port in the Attica region serving numerous travelers. The island does not have an airport, and traffic is primarily served by ro/pax ferries. The main port in the northwest is called Gavrion, and it is in a small bay that is hampered by side northerlies that accelerate through the valley on the north edge. The result is that ferries often have to dock with gusty katabatic winds with sustained speeds higher than 50 knots.

As the vessels get bigger and bigger, Gavrion's port basin remains the same, and the entrance limits the vessel’s size (in case of an aborted approach, it must be able to pass through in parallel, as in figures 1 and 3). Despite the serious risks, this is the standard at this and other ports in the region.

Figure 3: The ro/pax Superferry in an emergency abort maneuver at Gavrion under severe katabatic northerlies. Courtesy www.EnAndro.gr

What the master of the ferry Saonisos witnessed last week was a typical side gust against his ship, like many before him. Unluckily for him, a car tried to drive up the ramp for unknown reasons while his ship started drifting towards the southerly breakwater, resulting in ship’s ramp stuck under the vehicle.

Forced to decide if he would let the heavy winds push his ship aground on the adjacent breakwater, he ordered an emergency abort maneuver to end the docking, as every prudent master should do. He saved everyone, with the exception of minor damage to the car.

Instead of being applauded for his seamanship skills and his timely action to avert a disaster, he has been criminalized, fired and ridiculed internationally. A viral video circulating online shows the scene of the event, but not the context. It is his bad luck that Article 291 of the Greek penal code sees him as a criminal and not a hero.

Until the Greek government decides to face reality and invest in safe port infrastructure, Greek ferry masters should consider setting aside their skills and their sense of community service, and instead systematically abort similar port calls whenever poor weather conditions prevail. This would ensure safe operation despite inevitable interruptions in regular island ferry services.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.