Just a year ago, carbon credits were all the rage. Companies struck deal after deal in a market that analysts said would grow at breakneck speed. Then, it all started unwinding. Because Big Oil was using carbon credits, too. Apparently, it wasn’t supposed to go this way.

Back in 2022, Shell said it would invest some $100 million in developing what are commonly called carbon sinks or ecosystems that absorb more carbon dioxide than they emit—if they emit any at all. The supermajor then planned to turn those sinks into a business, issuing carbon credits to sell to other companies in need of decarbonization.

In September last year, however, Shell dropped those plans. The change of heart followed an investigation carried out by The Guardian and Die Zeit that revealed as much as 90% of the carbon credits verified as legitimate by the largest carbon credit certification company at the time were essentially worthless.

The revelation made some noise and cast doubt over the usefulness of carbon credits in the energy transition. Some critics have even called the indulgences modeled on the Medieval practice that the Catholic church had of selling forgiveness for sins. And the biggest sinner of them all is, of course, the oil and gas industry.

The oil and gas industry has no other way to decarbonize except by offsetting the emissions related to its operations through carbon credits. It is no accident that Occidental, the first oil and gas company to make an emissions commitment in the U.S. oil patch, is investing heavily in direct air capture, which it would tie to the issuance of a version of carbon credits to sell to big emitters.

It is no accident that every energy company with decarbonization plans has carbon credits included in these plans—because the only other way for oil and gas companies to cut their emissions is by essentially committing suicide. And they are far from the only ones.

Related: Russia Launches 200 Missiles at Ukrainian Energy Installations

Last month, the United Nations targeted carbon credits, also called carbon offsets, as an overused tool for emission reduction when companies should actually be cutting their real emissions, the FT reported at the time. Indeed, the UN drafted a document recommending that companies do not use credit offsets at all outside government-regulated programs such as the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme.

“I would hope and I would expect that serious organisations that are committed to protecting ecosystems . . . don’t shut down an avenue for channelling that carbon finance,” the head of BP’s carbon trading business unit said in comments on the UN document at the time.

Now, Bloomberg is reporting that Big Oil has become the ultimate winner from that carbon credit market that the UN so dislikes. Calling the energy industry “the main perpetrators of the global climate disaster,” the report states that Big Oil is using carbon credits in order to reduce its Scope 3 emissions instead of physically reducing these emissions.

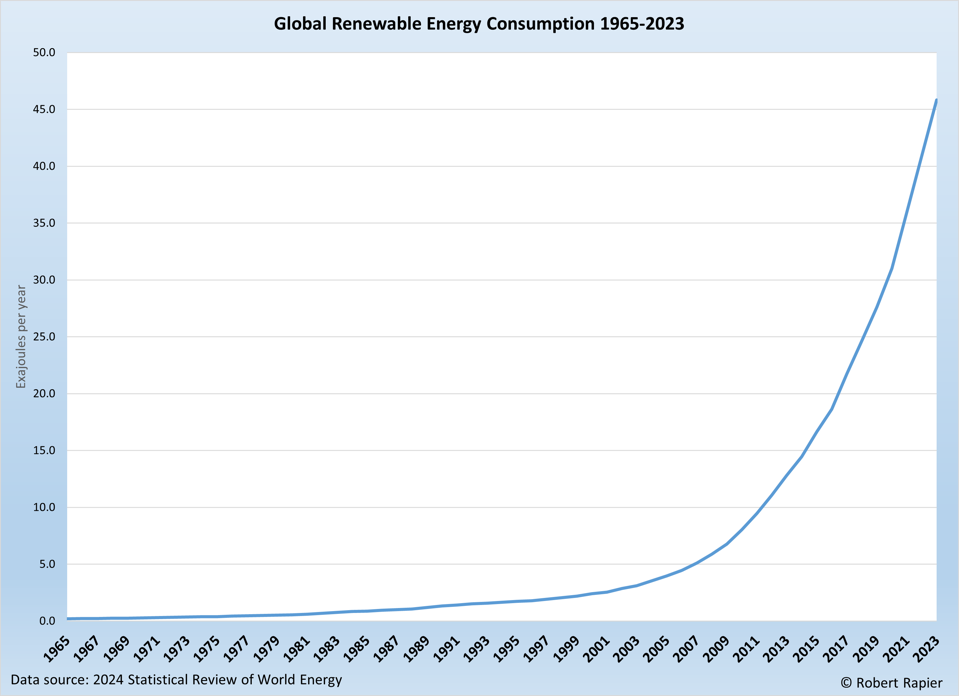

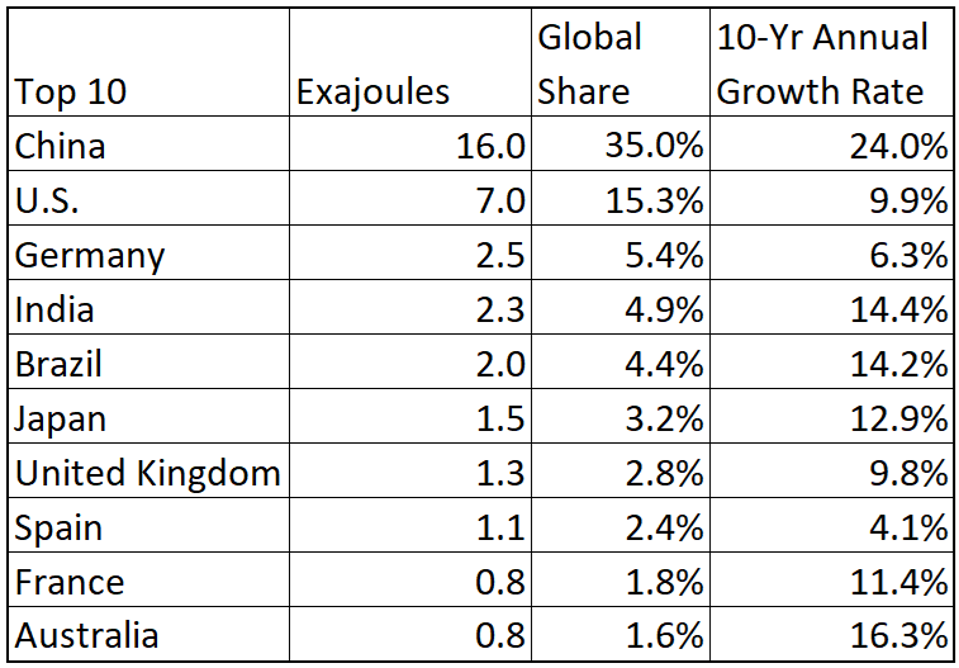

Yet there is a twist: Big Oil is far from the only industry doing this. Big Tech, a massive emitter that is only getting even more massive by the data center, is doing exactly the same thing—because there is no way Big Tech can source 100% of the electricity it needs from wind, solar, and batteries, not without carbon credits. Neither can any other industry that needs a reliable supply of energy around the clock.

Climate activists, however, have a problem exclusively with Big Oil, even though some involved in the transition have argued that Big Oil using carbon credits to offset their emissions is, in fact, part of the transition and, as such, a positive. Activists have argued—correctly—that carbon credits would help the oil and gas industry to survive for longer, implying their ultimate goal is the demise of that industry as the final solution to the climate change problem, regardless of the cost.

Businesses, meanwhile, have continued using carbon credits, with institutions emerging to make sure they are not worthless, as the Guardian/Zeit investigation revealed. The most influential of these, the Science Based Targets initiative, became the site of a scandal focused on those troublesome Scope 3 emissions earlier this year when it did an about-turn on its original policy, announcing it would, from now on, let companies count credits towards Scope 3 emission reductions.

The announcement caused an uproar among the SBTi’s employees, so the organization had to do another about-turn and go back to its original stance on Scope 3 emissions and credits. The reason for the uproar was the same reason that Bloomberg laments Big Oil’s position as what it called a big winner of the carbon credit system as a whole: not enough actual emission reductions.

Critics of the system are certainly right to point that out. From another perspective, however, the transition is about net zero rather than absolute zero. If carbon credits work as advertised, they should be contributing to an overall reduction in emissions. Also, it should not matter which industry uses these if the ultimate goal is to lower emissions of carbon dioxide.

By Irina Slav for Oilprice.com