Michel Bruneau, University at Buffalo

Tue, November 7, 2023

Acapulco's beachfront condo towers were devastated by Hurricane Otis. Rodrigo Oropeza/AFP via Getty Images

Acapulco wasn’t prepared when Hurricane Otis struck as a powerful Category 5 storm on Oct. 25, 2023. The short notice as the storm rapidly intensified over the Pacific Ocean wasn’t the only problem – the Mexican resort city’s buildings weren’t designed to handle anything close to Otis’ 165 mph winds.

While Acapulco’s oceanfront high-rises were built to withstand the region’s powerful earthquakes, they had a weakness.

Since powerful hurricanes are rare in Acapulco, Mexico’s building codes didn’t require that their exterior materials be able to hold up to extreme winds. In fact, those materials were often kept light to help meet earthquake building standards.

Otis’ powerful winds ripped off exterior cladding and shattered windows, exposing bedrooms and offices to the wind and rain. The storm took dozens of lives and caused billions of dollars in damage.

A US$130 million luxury condo building on the beach in Acapulco before Hurricane Otis struck on Oct. 25, 2023. Hamid Arabzadeh, PhD., P.Eng.

The same Acapulco condo tower after Hurricane Otis. Hamid Arabzadeh, PhD., P.Eng.

I have worked on engineering strategies to enhance disaster resilience for over three decades and recently wrote a book, “The Blessings of Disaster,” about the gambles humans take with disaster risk and how to increase resilience. Otis provided a powerful example of one such gamble that exists when building codes rely on probabilities that certain hazards will occur based on recorded history, rather than considering the severe consequences of storms that can devastate entire cities.

The fatal flaw in building codes

Building codes typically provide “probabilistic-based” maps that specify wind speeds that engineers must consider when designing buildings.

The problem with that approach lies in the fact that “probabilities” are simply the odds that extreme events of a certain size will occur in the future, mostly calculated based on past occurrences. Some models may include additional considerations, but these are still typically anchored in known experience.

This is all good science. Nobody argues with that. It allows engineers to design structures in accordance with a consensus on what are deemed acceptable return periods for various hazards, referring to the likelihood of those disasters occurring. Return periods are a somewhat arbitrary assessment of what is a reasonable balance between minimizing risk and keeping building costs reasonable.

However, probabilistic maps only capture the odds of the hazard occurring. A probabilistic map might specify a wind speed to consider for design, irrespective of whether that given location is a small town with a few hotels or a megapolis with high-rises and complex urban infrastructure. In other words, probabilistic maps do not consider the consequences when an extreme hazard exceeds the specified value and “all hell breaks loose.”

How probability left Acapulco exposed

According to the Mexican building code, hotels, condos and other commercial and office buildings in Acapulco must be designed to resist 88 mph winds, corresponding to the strongest wind likely to occur on average once every 50 years there. That’s a Category 1 storm.

A 200-year return period for wind is used for essential facilities, such as hospital and school buildings, corresponding to 118 mph winds. But over a building’s life span of, say, 50 years, that still leaves a 22% change that winds exceeding 118 mph will occur (yes, the world of statistics is that sneaky).

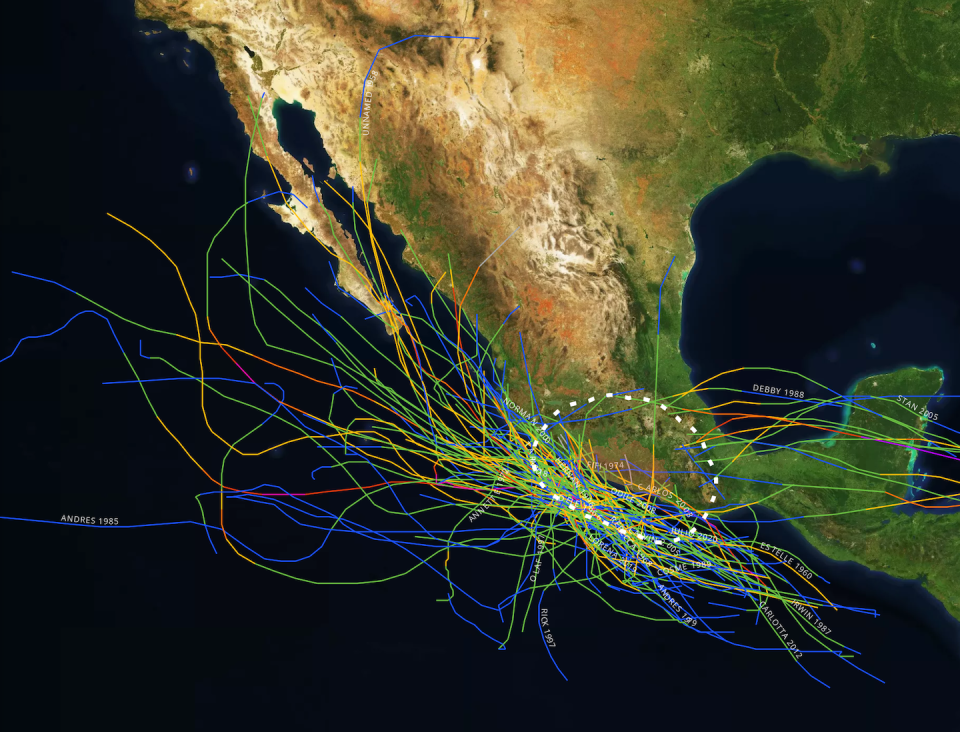

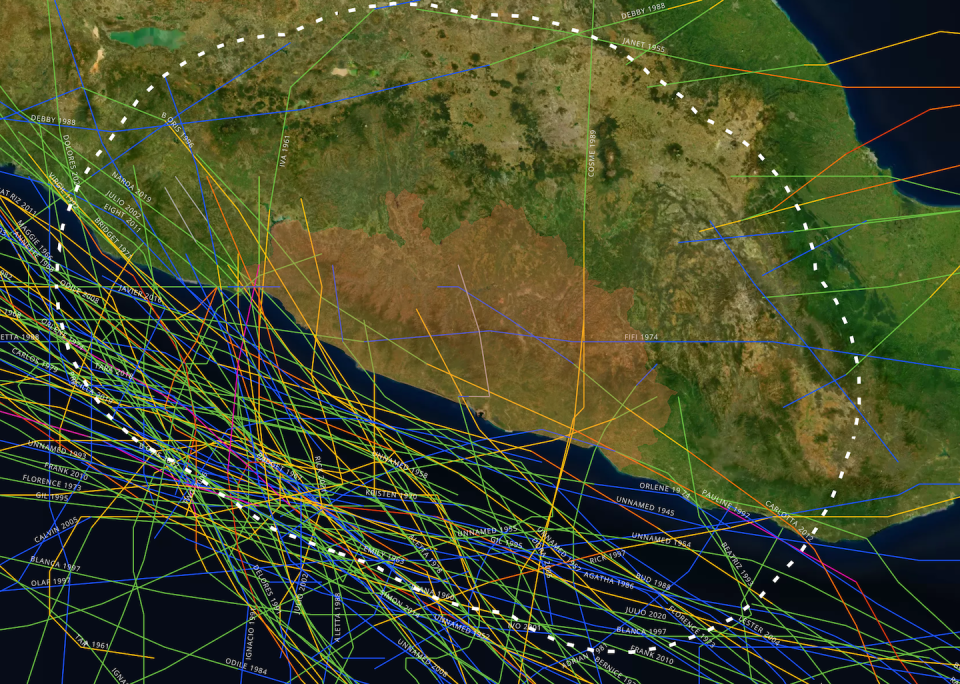

Mexico’s hurricane history in storm tracks. NOAA

A century of hurricane storm tracks near Acapulco show several offshore storms that brought strong winds and rain to the city, but few direct landfalls. Acapulco Bay is in the center of the map on the coast. Red, pink and purple lines are categories 3, 4 and 5, respectively. NOAA

The probability wind maps for both return periods show Acapulco experiences lower average wind speeds than much of the 400 miles of Mexican coast north of the city. Yet, Acapulco is a major city, with a metropolitan population of over 1 million. It also has more than 50 buildings taller than 20 stories, according to the SkyscraperPage, a database of skyscrapers, and it is the only city with buildings that tall along that stretch of the Pacific coast.

Designing for a 50-year return period in this case is questionable, as it implies a near 100% chance of encountering wind exceeding this design value for a building with a 50-year life span or greater.

Florida faces similiar challenges

The shortcomings of probabilistic-based maps that specify wind speeds have also been observed in the United States. For example, new buildings along most of Florida’s coast must be able to resist 140 mph winds or greater, but there are a few exceptions. One is the Big Bend area where Hurricane Idalia made landfall in 2023. Its design wind speed is about 120 mph instead.

A 2023 update to the Florida Building Code raised the minimum wind speed to approximately 140 mph in Mexico Beach, the Panhandle town that was devastated by Hurricane Michael in 2018. The Big Bend exception may be the next one to be eliminated.

Acapulco’s earthquake design weakness

A saving grace for Acapulco is that it is located in one of Mexico’s most active seismic risk zones – for example, a magnitude 7 earthquake struck nearby in 2021. As a result, the lateral-load-resisting structural systems in tall buildings there are designed to resist seismic forces that are generally larger than hurricane forces.

However, a drawback is that the larger the mass of a building, the larger the seismic forces the building must be designed to resist. Consequently, light materials were typically used for the cladding – the exterior surface of the building that protects it against the weather – because that translates into lower seismic forces. This light cladding was not able to withstand hurricane-force winds.

Had the cladding not failed, the full wind forces would have been transferred to the structural system, and the buildings would have survived with little or no damage.

A ‘good engineering approach’ to hazards

A better building code could go one step beyond “good science” probabilistic maps and adopt a “good engineering approach” by taking stock of the consequences of extreme events occurring, not just the odds that they will.

In Florida, the incremental cost of designing for wind speeds of 140 mph rather than 120 mph is marginal compared to total building cost, given that cladding able to resist more than 140 mph is already used in nearly all of the state. In Acapulco, with the spine of buildings already able to resist earthquake forces much larger than hurricane forces, designing cladding that can withstand stronger hurricane-level forces is likely to be an even smaller percentage of total project cost.

Someday, the way that design codes deal with extreme events such as hurricanes, not only in Mexico, will hopefully evolve to more broadly account for what is at risk at the urban scale. Unfortunately, as I explain in “The Blessings of Disaster,” we will see more extreme disasters before society truly becomes disaster resilient.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world.

It was written by: Michel Bruneau, University at Buffalo.

Read more:

Dreaming of beachfront real estate? Much of Florida’s coast is at risk of storm erosion that can cause homes to collapse, as Daytona just saw

Some coastal areas are more prone to devastating hurricanes – a meteorologist explains why

Michel Bruneau does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Grieving Acapulco mother fears for future after breadwinner son's death in hurricane

Wed, November 8, 2023

Aftermath of Hurricane Otis in Acapulco

By Jose Luis Gonzalez

ACAPULCO, Mexico (Reuters) - Since Hurricane Otis killed her fisherman son in the Mexican beach resort of Acapulco last month, 69-year-old Manuela Garcia Estrada worries she will not be able to cope now that her main economic support is gone.

"He was the one who maintained me, he was the one who made sure I was well" said Garcia, fighting back tears as she took the body of her 47-year-old son, Hugo Sosa Garcia, for burial after he drowned in Acapulco bay during the storm.

Garcia, who has a surviving son who is disabled and cannot work, and another living elsewhere in Mexico, is one of thousands of Acapulco residents whose lives were shattered by Otis, the most powerful hurricane ever to strike the country's Pacific coast.

She, Hugo, her disabled son and two dogs shared a house which she said had been "completely destroyed" by Otis.

"How will I rebuild it, what am I going to do?" she asked.

Wreaking havoc in the city of nearly 900,000, Otis, a Category 5 hurricane, killed dozens of people and left thousands more without roofs over their heads. Dozens more are still missing. Some business leaders fear the city will not recover until 2025.

On Monday, dozens of people marched through central Mexico City to protest what they saw as a lack of government support after widespread looting, power cuts and destruction of ATMs left supplies of food and water running low in Acapulco.

President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has launched a $3.4 billion recovery plan and pledged to get Acapulco back on its feet quickly. A few major supermarkets have begun reopening.

The Army has vowed to massively ramp up its presence there, almost tripling the National Guard's deployment in Acapulco's home state of Guerrero.

Garcia said her son's death is still not sinking in.

"I'll be waiting for my son to come home," she said. "He always brought food: 'What do you want to eat today, mom?'"

(Reporting by Jose Luis Gonzalez; Writing by Dave Graham; Editing by Sandra Maler)

View comments (7)

Mexico plans major military presence in Acapulco after hurricane

Reuters

Tue, November 7, 2023

MEXICO CITY (Reuters) - Mexico's government on Tuesday unveiled a plan to nearly triple the National Guard deployment in the state of Guerrero to massively ramp up security in Acapulco after the crime-plagued beach resort was devastated by a hurricane last month.

Hurricane Otis, the strongest to ever hit Mexico's Pacific coast, hammered Acapulco, killing dozens of people, causing billions of dollars in damage and sparking widespread looting.

The influx of National Guard troops to the stricken city will make Guerrero, which lies in southern Mexico, home to the biggest deployment of any state, the government said.

"This plan seeks to have the National Guard in the municipality of Acapulco permanently to continue guaranteeing security," Defense Minister Luis Cresencio Sandoval said at a press conference with President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador.

In Acapulco, the National Guard presence will increase from 360 members to 9,860, Sandoval said. Guerrero's total will rise to 14,620 from 5,120 at present.

The number is more than double the nearly 7,000 troops stationed in the violence-ravaged central state of Guanajuato, which has had the highest National Guard presence.

Mexico will set up 38 bases across Acapulco, a city of nearly 900,000 people, to house the troops.

Crime has for years been a blight on Acapulco, which in 2022 was among the 10 most violent cities in the world, according to data published by a Mexican civil society group, the Citizen Council for Public Security and Criminal Justice.

At times during the past dozens years the city has been the most violent in Mexico, according to the group. While its homicide rate has eased somewhat, recent months have seen a slew of violent incidents, including a journalist's brazen murder and the deadly ambush of 13 police officers near the city.

The creation of the National Guard has been a pillar of Lopez Obrador's security strategy and a target of critics who argue his policies have failed to make Mexico safer, pointing to record numbers of homicides on his watch.

(Reporting by Brendan O'Boyle; editing by Jonathan Oatis)

Mexico Hurricane Otis

Soldiers guard the streets while residents take items from local stores after Hurricane Otis ripped through Acapulco, Mexico, Oct. 26, 2023.

(AP Photo/Marco Ugarte, File)

Two weeks after Hurricane Otis, Acapulco shadow of former self

Samir Tounsi

Tue, November 7, 2023

Saul Parra is searching for his brother Fernando, a boat crew member who disappeared during Hurricane Otis (FRANCISCO ROBLES)

Families search for missing relatives as shops and bars gradually reopen -- two weeks after a devastating hurricane, Mexico's beachside city of Acapulco is struggling to regain a semblance of normality.

A few bathers soak up the sun on Manzanillo beach, near residential buildings whose windows were smashed by winds that reached 165 miles (270 kilometers) per hour.

At the feet of the 27-floor Marena residence in the exclusive Punta Diamante district, mattresses and cushions lie amid debris on the beach.

Inspired by the shape of a ship's sail filled with wind, its luxury apartments once sold for more than one and a half million dollars each, but they have been left uninhabitable by the fury of Otis.

Many businesses have not only been damaged but also looted.

Schools remain closed until further notice.

In Acapulco Bay, navy divers search for missing people among destroyed or submerged yachts.

At least 48 were killed and more than 30 are still unaccounted for after Hurricane Otis came ashore in the early hours of October 25 as a scale-topping category 5 storm, according to authorities.

Relatives of four crew members from the Litos yacht who disappeared reunite by the sea for the first time.

"We know nothing. I think the government is hiding the truth from us," Saul Parra says next to a missing persons poster for his brother Fernando.

"It's time to raise our voice. Time is passing. If we have a chance of finding them alive, it's slipping through our hands," he adds.

- Aid efforts -

On the city's main beachfront avenue, dozens of residents queue for a free dish of meat and rice.

"Every day we prepare around 4,000 meals," says Brian Chavez, 22, a volunteer for World Central Kitchen, an organization that provides food during humanitarian crises.

Elsewhere, the navy distributes toilet paper -- part of a wider aid effort by Mexico's authorities.

A few meters away, a taco restaurant has resumed service.

The kebab-style meat rotates on a spit as Mexican music plays in the background.

On Monday, a major supermarket near the beach reopened its doors, allowing customers to enter in groups of 10, under the control of the army.

"I'm very happy to be able to obtain basic necessities," says Yameli, a mother who came with her two daughters.

"We bought tomatoes, vegetables, ham, some fruit juice. Some products were missing, like tuna and bread," she says.

In the middle-class Progreso district, away from the seafront, trash cans pile up on the street in the humid heat.

"It's starting to stink. They need to be collected urgently" says resident Laura Salvide, who fears the insanitary conditions will cause outbreaks of disease.

A lack of drinking water is another problem, she complains.

A few streets away, garbage collectors are at work.

- Guarding neighborhoods -

Tangled power lines hang from pylons in the city, ripped down by the hurricane.

Teams from the state electricity company have been hard at work for the past fortnight repairing damage.

Even so, part of Acapulco is still plunged into darkness after nightfall, including Campeche Street, where residents have made barricades with wooden pallets and corrugated metal sheets.

"We do it for our safety," says Alfredo Villalobos.

Some residents in the city have even been seen guarding their districts with machetes and baseball bats.

On Monday morning, at the other end of Campeche Street, a decapitated body was found, according to an AFP photographer.

Suspicion quickly fell on criminal gangs who have been settling scores for years in the region, tarnishing Acapulco's fun-loving reputation.

Down by beach, a night-time bar pumps out loud music on an unlit street.

Rubble is still piled up in front of the establishment.

The city's nightlife is gradually reawakening, but it is not the same as before Otis.

"We have a really reduced menu," says Andres Boleo.

He says he makes a round trip of hundreds of miles (kilometers) to collect supplies for his snack bar.

Despite the difficulties, Boleo is sure of one thing: "Acapulco will always be Acapulco."

Two weeks after Hurricane Otis, Acapulco shadow of former self

Samir Tounsi

Tue, November 7, 2023

Saul Parra is searching for his brother Fernando, a boat crew member who disappeared during Hurricane Otis (FRANCISCO ROBLES)

Families search for missing relatives as shops and bars gradually reopen -- two weeks after a devastating hurricane, Mexico's beachside city of Acapulco is struggling to regain a semblance of normality.

A few bathers soak up the sun on Manzanillo beach, near residential buildings whose windows were smashed by winds that reached 165 miles (270 kilometers) per hour.

At the feet of the 27-floor Marena residence in the exclusive Punta Diamante district, mattresses and cushions lie amid debris on the beach.

Inspired by the shape of a ship's sail filled with wind, its luxury apartments once sold for more than one and a half million dollars each, but they have been left uninhabitable by the fury of Otis.

Many businesses have not only been damaged but also looted.

Schools remain closed until further notice.

In Acapulco Bay, navy divers search for missing people among destroyed or submerged yachts.

At least 48 were killed and more than 30 are still unaccounted for after Hurricane Otis came ashore in the early hours of October 25 as a scale-topping category 5 storm, according to authorities.

Relatives of four crew members from the Litos yacht who disappeared reunite by the sea for the first time.

"We know nothing. I think the government is hiding the truth from us," Saul Parra says next to a missing persons poster for his brother Fernando.

"It's time to raise our voice. Time is passing. If we have a chance of finding them alive, it's slipping through our hands," he adds.

- Aid efforts -

On the city's main beachfront avenue, dozens of residents queue for a free dish of meat and rice.

"Every day we prepare around 4,000 meals," says Brian Chavez, 22, a volunteer for World Central Kitchen, an organization that provides food during humanitarian crises.

Elsewhere, the navy distributes toilet paper -- part of a wider aid effort by Mexico's authorities.

A few meters away, a taco restaurant has resumed service.

The kebab-style meat rotates on a spit as Mexican music plays in the background.

On Monday, a major supermarket near the beach reopened its doors, allowing customers to enter in groups of 10, under the control of the army.

"I'm very happy to be able to obtain basic necessities," says Yameli, a mother who came with her two daughters.

"We bought tomatoes, vegetables, ham, some fruit juice. Some products were missing, like tuna and bread," she says.

In the middle-class Progreso district, away from the seafront, trash cans pile up on the street in the humid heat.

"It's starting to stink. They need to be collected urgently" says resident Laura Salvide, who fears the insanitary conditions will cause outbreaks of disease.

A lack of drinking water is another problem, she complains.

A few streets away, garbage collectors are at work.

- Guarding neighborhoods -

Tangled power lines hang from pylons in the city, ripped down by the hurricane.

Teams from the state electricity company have been hard at work for the past fortnight repairing damage.

Even so, part of Acapulco is still plunged into darkness after nightfall, including Campeche Street, where residents have made barricades with wooden pallets and corrugated metal sheets.

"We do it for our safety," says Alfredo Villalobos.

Some residents in the city have even been seen guarding their districts with machetes and baseball bats.

On Monday morning, at the other end of Campeche Street, a decapitated body was found, according to an AFP photographer.

Suspicion quickly fell on criminal gangs who have been settling scores for years in the region, tarnishing Acapulco's fun-loving reputation.

Down by beach, a night-time bar pumps out loud music on an unlit street.

Rubble is still piled up in front of the establishment.

The city's nightlife is gradually reawakening, but it is not the same as before Otis.

"We have a really reduced menu," says Andres Boleo.

He says he makes a round trip of hundreds of miles (kilometers) to collect supplies for his snack bar.

Despite the difficulties, Boleo is sure of one thing: "Acapulco will always be Acapulco."

No comments:

Post a Comment