Juneteenth — June 19th, also known as Emancipation Day — is one of the commemorations of people seizing their freedom in the United States.

Celebrate. But We Can’t Teach?

This beautiful tradition of Black freedom should be taught in school.

Yet, if the right wing has its way, it will be illegal to teach students about Juneteenth. At least 44 states have passed or proposed legislation to prohibit teaching about structural racism. The goal of conservative legislators: to outlaw teaching about the founding of this country on slavery and genocide or the long Black freedom struggle.

Some statewide bills ban teaching about the very structures and systems that led to enslavement as well as how these structures continue to manifest in policing, redlining, voter suppression laws, and more.

But educators around the country continue to pledge to teach the truth about structural racism.

This month, educators in at least 170 sites around the country are participating in the Teach Truth campaign. They are rallying to defend the right to teach truthfully, to protest book bans, and to defend LGBTQ+ rights.

It is time to redouble our commitment to teach about the long Black freedom struggle, including Juneteenth.

Background on Juneteenth

Here are key points from scholars Greg Carr, Christopher Wilson, and Clint Smith on the history beyond the traditional textbook narrative about Juneteenth.

Black Troops Spreading the Word with Every Marching Foot

By Howard University professor Greg Carr, transcribed from a Teach the Black Freedom Struggle Online Class

While General Granger read the Emancipation Proclamation off that veranda in Galveston, there were at least nine regiments of the United States Colored Troops marking their way through Texas, the last of the 10 states in the Confederacy to give up. Black troops, some of those same Black troops that have captured Richmond, those Black troops were now in Texas. So while Granger makes the formal announcement on June 19th, and a year later to the day, Black folks start celebrating Juneteenth formally, those Black troops are spreading the word with every marching foot as they come across the South.

June 19th is the official day marking these emancipation celebrations as it formally comes into the African awareness in Texas. But the dates are usually linked to whenever people found out they were free, which is why in Mississippi, in Alabama, in Arkansas, in Oklahoma, you might see an August date or July date. This is described in O Freedom: Afro-American Emancipation Celebrations by William Wiggins. What we see in Galveston, Texas, in 1865, is also connected to the Caribbean, described in Howard University professor Jeffrey Kerr-Ritchie’s book on Emancipation Day celebrations called Rites of August First: Emancipation Day in the Black Atlantic World. There is also Decoration Day. We think about the roots of what become Memorial Day, the idea of honoring our ancestors who made the ultimate sacrifice, by placing flowers on their graves and you see that coming out of South Carolina. There’s a very good book called Conjuring Freedom that talks about that South Carolina regiment of Colored Troops and the beautiful Ed Dwight monument on the South Carolina State House grounds.

African American History Monument by Ed Dwight, State Capitol Grounds, Columbia, South Carolina. Source: Alamy

. . .In many of the churches in the North — Boston, Philadelphia, New York — people prayed on the last day of December 1862. They brought in the New Year with the expectation that now it was time to get up off our knees, go get some guns or support those with guns, and make this Emancipation Proclamation stand up since it didn’t apply unless you were in control of the place that you went to in battles.

And, of course, January 1 was the celebration day for a lot of Black people for years because of the Emancipation Proclamation. Minister Silas X. Floyd said, “May God forget my people, if we forget this day,” and that was January 1, not June 19. That’s another one of many examples.

It Was Not the “News” That Traveled Slowly — It Was “Power”

By Christopher Wilson, Curator and Chair, Division of Home and Community Life, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History

Very often Juneteenth is presented as a story of “news” of the Emancipation Proclamation “traveling slowly” to the Deep South and Texas, but it was really a story of power traveling slowly, and of freedom being seized. Due to the telegraph, newspapers and the United States Army spread out all across the country to put down the slaveholders’ rebellion, word of Lincoln’s order spread all over the South immediately after it was announced in September 1862 and took effect in January 1863.

While enslaved Black people in far off places like Texas were often kept in the dark and fed a pro-slavery narrative of the events of the war and the nation, whether they received word of the order wasn’t so much the point. As with an incarcerated prisoner who may be told she’s free, until the prison bars are unlocked that word only results in theoretical freedom. The news that the United States government was declaring enslaved people in areas still in rebellion against the nation forever free was incredibly important to the enslaved and the country, but what mattered more than that news was the power and will to enforce it. General Granger’s order was less directed toward offering news to the enslaved than it was about commanding lawless human traffickers and insurrectionists to obey the Proclamation issued two years earlier.

While enslaved Black people in far off places like Texas were often kept in the dark and fed a pro-slavery narrative of the events of the war and the nation, whether they received word of the order wasn’t so much the point. As with an incarcerated prisoner who may be told she’s free, until the prison bars are unlocked that word only results in theoretical freedom. The news that the United States government was declaring enslaved people in areas still in rebellion against the nation forever free was incredibly important to the enslaved and the country, but what mattered more than that news was the power and will to enforce it. General Granger’s order was less directed toward offering news to the enslaved than it was about commanding lawless human traffickers and insurrectionists to obey the Proclamation issued two years earlier.

Even following the arrival of the power to enforce the emancipation order in the form of the United States Army, enslaved people were left with much of the responsibility to seize their own freedom. As had been the case since the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, the position of the federal government on ending slavery in much of the country offered the enslaved the chance to take their freedom into their own hands and promised that if they could get themselves to an area not controlled by rebels, that this theoretical freedom would be fulfilled. This drive and requirement for self-emancipation has been consistent through the story of Black American history.

The Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 made school segregation unconstitutional, but it was men, women and children who put their bodies on the line to actually desegregate schools years later. The Morgan v. Virginia decision in 1946 made segregation on interstate buses unconstitutional, but it was Freedom Riders who were beaten and burned who desegregated transit in 1961.

The promise of freedom implied in the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation was real and very important, as was the eventual enforcement of that order by the Army across the South and into Texas, but the enslaved were ultimately the ones to truly decide what freedom meant to them and who worked to make it a reality.

Long History of Commemorations

By journalist and educator Clint Smith, in an excerpt from his 2021 book, How the Word Is Passed (page 187)

The earliest iterations of Juneteenth in Texas, which began following the end of the Civil War, ranged from ceremonial readings of the Emancipation Proclamation to Black newspapers printing images of Abraham Lincoln in their pages, testament to a man who had already begun to take on a legendary and even mythical status among many in the Black community.

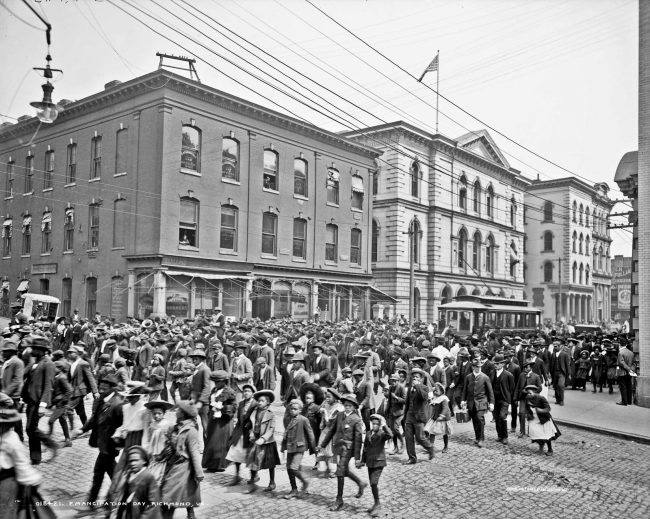

Parade in Richmond, Virginia for Emancipation Day, April 3, 1905. Source: Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries

Other celebrations included church services in which preachers had the congregation give thanks for their freedom while encouraging them to be relentless in the ongoing struggle for racial equity. Often there were parades, large displays of song and celebration that shook the street. And in the afternoons there were massive feasts, the sort of spread that people looked forward to all year: spareribs, fried chicken, black-eyed peas. . . .

Other celebrations included church services in which preachers had the congregation give thanks for their freedom while encouraging them to be relentless in the ongoing struggle for racial equity. Often there were parades, large displays of song and celebration that shook the street. And in the afternoons there were massive feasts, the sort of spread that people looked forward to all year: spareribs, fried chicken, black-eyed peas. . . .

With the threat of lynching always there for Black Southerners, some celebrations across the country disappeared from public view and into private homes and Black churches.

Teaching Resources

Watch Professor Greg Carr’s Teach the Black Freedom Struggle conversation with high school teacher Jessica Rucker about Juneteenth and Reconstruction. | The National Museum of African American History and Culture offers the digital resource, Juneteenth: Celebration of Resilience. |

Also recommended: Juneteenth Observances Promote ‘Absolute Equality’ by Coshandra Dillard in Learning for Justice.

We feature a special broadcast marking the Juneteenth federal holiday that commemorates the day in 1865 when enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, learned of their freedom more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation. We begin with our 2021 interview with historian Clint Smith, originally aired a day after President Biden signed legislation to make Juneteenth the first new federal holiday since Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Smith is the author of How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America. “When I think of Juneteenth, part of what I think about is the both/andedness of it,” Smith says, “that it is this moment in which we mourn the fact that freedom was kept from hundreds of thousands of enslaved people for years and for months after it had been attained by them, and then, at the same time, celebrating the end of one of the most egregious things that this country has ever done.” Smith says he recognizes the federal holiday marking Juneteenth as a symbol, “but it is clearly not enough.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Today, a Democracy Now! special on this, the newly created Juneteenth federal holiday, which marks the end of slavery in the United States. The Juneteenth commemoration dates back to the last days of the Civil War, when Union soldiers landed in Galveston, Texas — it was June 19th, 1865 — with news that the war had ended, and enslaved people learned they were freed. It was two-and-a-half years after President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

In 2021, President Biden signed legislation to make Juneteenth the first new federal holiday since Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day. The day after Biden signed the legislation, I spoke to the writer and poet Clint Smith, author of How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America. I began by asking him about traveling to Galveston, Texas, and his feelings on Juneeteenth becoming a federal holiday.

CLINT SMITH: As you mentioned, I went to Galveston, Texas. I’ve been writing this book for four years, and I went two years ago. And it was marking the 40th anniversary of when Texas had made Juneteenth a state holiday. And it was the Al Edwards Prayer Breakfast. The late Al Edwards Sr. is the state legislator, Black state legislator, who made possible and advocated for the legislation that turned Juneteenth into a holiday, a state holiday in Texas.

And so I went, in part, because I wanted to spend time with people who were the actual descendants of those who had been freed by General Gordon Granger’s General Order No. 3. And it was a really remarkable moment, because I was in this place, on this island, on this land, with people for whom Juneteenth was not an abstraction. It was not a performance. It was not merely a symbol. It was part of their tradition. It was part of their lineage. It was an heirloom that had been passed down, that had made their lives possible. And so, I think I gained a more intimate sense of what that holiday meant.

And to sort of broaden, broaden out more generally, you spoke to how it was more than two-and-a-half years after the Emancipation Proclamation, and it was an additional two months after General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, effectively ending the Civil War. So it wasn’t only two years after the Emancipation Proclamation; it was an additional two months after the Civil War was effectively over.

And so, for me, when I think of Juneteenth, part of what I think about is the both/andedness of it, that it is this moment in which we mourn the fact that freedom was kept from hundreds of thousands of enslaved people for years and for months after it had been attained by them, and then, at the same time, celebrating the end of one of the most egregious things that this country has ever done.

And I think what we’re experiencing right now is a sort of marathon of cognitive dissonance, in the way that is reflective of the Black experience as a whole, because we are in a moment where we have the first new federal holiday in over 40 years and a moment that is important to celebrate, the Juneteenth, and to celebrate the end of slavery and to have it recognized as a national holiday, and at the same time that that is happening, we have a state-sanctioned effort across state legislatures across the country that is attempting to prevent teachers from teaching the very thing that helps young people understand the context from which Juneteenth emerges.

And so, I think that we recognize that, as a symbol, Juneteenth is not — that it matters, that it is important, but it is clearly not enough. And I think the fact that Juneteenth has happened is reflective of a shift in our public consciousness, but also of the work that Black Texans and Black people across this country have done for decades to make this moment possible.

AMY GOODMAN: And can you explain more what happened in Galveston in 1865 and, even as you point out, what the Emancipation Proclamation actually did two-and-a-half years before?

CLINT SMITH: Right. So, the Emancipation Proclamation is often a widely misunderstood document. So, it did not, sort of wholesale, free the enslaved people throughout the Union. It did not free enslaved people in the Union. In fact, there were several border states that were part of the Union that continued to keep their enslaved laborers, states like Kentucky, states like Delaware, states like Missouri. And what it did was it was a military edict that was attempting to free enslaved people in Confederate territory. But the only way that that edict would be enforced is if Union soldiers went and took that territory.

And so, part of what many enslavers realized — and realized correctly — was that Texas would be one of the last frontiers that Union soldiers would be able to come in and force the Emancipation Proclamation — if they ever made it there in the first place, because this was two years prior to the end of the Civil War. And so, you had enslavers from Virginia and from North Carolina and from all of these states in the upper South who brought their enslaved laborers and relocated to Texas, in ways that increased the population of enslaved people in Texas by the tens of thousands.

And so, when Gordon Granger comes to Texas, he is making clear and letting people know that the Emancipation Proclamation had been enacted, in ways that because of the topography of Texas and because of how spread out and rural and far apart from different ecosystems of information many people were, a lot of enslaved people didn’t know that the Emancipation Proclamation had happened. And some didn’t even know that General Lee had surrendered at Appomattox two months prior. And so, part of what this is doing is making clear to the 250,000 enslaved people in Texas that they had actually been granted freedom two-and-a-half years prior and that the war that this was all fought over had ended two months before.

AMY GOODMAN: During the ceremony making Juneteenth a federal holiday, President Biden got down on his knee to greet Opal Lee, the 94-year-old activist known as the Grandmother of Juneteenth. This is Biden speaking about Lee.

PRESIDENT JOE BIDEN: As a child growing up in Texas, she and her family would celebrate Juneteenth. On Juneteenth 1939, when she was 12 years old, a white mob torched her family home. But such hate never stopped her, any more than it stopped the vast majority of you I’m looking at from this podium. Over the course of decades, she has made it her mission to see that this day came. It was almost a singular mission. She has walked for miles and miles, literally and figuratively, to bring attention to Juneteenth, to make this day possible.

AMY GOODMAN: And this is Opal Lee speaking at Harvard School of Public Health.

OPAL LEE: I don’t want people to think Juneteenth is just one day. There is too much educational components. We have too much to do. I even advocate that we do Juneteenth, that we celebrate freedom from the 19th of June to the Fourth of July, because we weren’t free on the Fourth of July, 1776. That would be celebrating freedom — do you understand? — if we were able to do that.

AMY GOODMAN: And that is Opal Lee, considered the Grandmother of Juneteenth. And, Clint, one of the things you do in your book is you introduce us to grassroots activists. This doesn’t come from the top; this comes from years of organizing, as you point out, in Galveston itself and with people like — not that there’s anyone like — Opal Lee.

CLINT SMITH: Yeah, no, absolutely. Part of what this book is doing, it is an attempt to uplift the stories of people who don’t often get the attention that they deserve in how they shape the historical record. So, that means the public historians who work at these historical sites and plantations. That means the museum curators. That means the activists and the organizers, people like Take ’Em Down NOLA in New Orleans, who pushed the City Council and the mayor to make possible the fact that in 2017 these statues would come down, several Confederate statues in my hometown, in New Orleans.

And part of — when I think about someone like Miss Opal Lee, part of what I think about is our proximity to this period of history, right? Slavery existed for 250 years in this country, and it’s only not existed for 150. And, you know, the way that I was taught about slavery, growing up, in elementary school, we were made to feel as if it was something that happened in the Jurassic age, that it was the flint stone, the dinosaurs and slavery, almost as if they all happened at the same time. But the woman who opened the National Museum of African American History and Culture alongside the Obama family in 2016 was the daughter of an enslaved person — not the granddaughter or the great-granddaughter or the great-great-granddaughter. The daughter of an enslaved person is who opened this museum of the Smithsonian in 2016. And so, clearly, for so many people, there are people who are alive today who were raised by, who knew, who were in community with, who loved people who were born into intergenerational chattel bondage. And so, this history that we tell ourselves was a long time ago wasn’t, in fact, that long ago at all.

And part of what so many activists and grassroots public historians and organizers across this country recognize is that if we don’t fully understand and account for this history, that actually wasn’t that long ago, that in the scope of human history was only just yesterday, then we won’t fully understand our contemporary landscape of inequality today. We won’t understand how slavery shaped the political, economic and social infrastructure of this country. And when you have a more acute understanding of how slavery shaped the infrastructure of this country, then you’re able to more effectively look around you and see how the reason one community looks one way and another community looks another way is not because of the people in those communities, but is because of what has been done to those communities, generation after generation after generation. And I think that that is central to the sort of public pedagogy that so many of these activists and organizers who have been attempting to make Juneteenth a holiday and bring attention to it as an entry point to think more wholly and honestly about the legacy of slavery have been doing.

AMY GOODMAN: During an interview on CNN, Democratic Congressmember Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez called out the 14 Republican congressmembers — all white men — who voted against making Juneteenth a federal holiday.

REP. ALEXANDRIA OCASIO–CORTEZ: This is pretty consistent with, I think, the Republican base, and it’s — whether it’s trying to fight against teaching basic history around racism and the role of racism in U.S. history to — you know, there’s a direct through line from that to denying Juneteenth, the day that is widely recognized and celebrated as a symbolic kind of day to represent the end of slavery in the United States.

AMY GOODMAN: If you could respond to that, Clint Smith, and also the fact that on the same day, yesterday, the Senate minority leader said they would not be supporting the For the People Act?

CLINT SMITH: Yeah, I mean, I think —

AMY GOODMAN: The Voting Rights Act.

CLINT SMITH: Absolutely. I think, very clearly, the critical race theory — the idea of it is being used as a bogeyman, and it is being misrepresented and distorted by people who don’t even know what critical race theory is, right? So we should be clear that the thing that people are calling critical race theory is just — that is the language that they are using to talk about the idea of teaching any sort of history that rejects the idea that America is a singularly exceptional place, and that we should not account for the history of harm that has been enacted to create opportunities and intergenerational wealth for millions of people, that has come at the direct expense of millions and millions of other people across generations.

And so, part of what is happening in these state legislatures across the country with regard to the effort to push back against teaching of history — 1619 Project, critical race theory and the like — is a recognition that we have developed in this country a more sophisticated understanding, a more sophisticated framework, a more sophisticated public lexicon, with which to understand how slavery — how racism was not just an interpersonal phenomenon, it was a historic one, it was a structural one, it was a systemic one.

AMY GOODMAN: I want you to talk more about your book, How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America. Can you talk about the journey you took — you were just mentioning where you grew up, in Louisiana, the map of the streets of Louisiana — and why you feel it is so critical not only to look at the South, but your chapter on New York is something that people will be — many will be shocked by, the level of — when people talk about the South and slavery, that New York, of course, had enslaved people?

CLINT SMITH: It did. It was really important for me to include a chapter on New York City, and a place in the North, more broadly, in part because, you know, while the majority of places I visit are in the South, because the South is where slavery was saturated and where it was most intimately tied the social and economic infrastructure of that society, it most certainly also existed in the North.

What a lot of people don’t know is that New York City, for an extended period of time, was the second-largest slave port in the country, after Charleston, South Carolina; that in 1860, on the brink of the Civil War, when South Carolina was about to secede from the Union after the election of Abraham Lincoln, that New York City’s mayor, Fernando Wood, proposed that New York City should also secede from the Union alongside the Southern states, because New York’s financial and political infrastructure were so deeply entangled and tied to the slavocracy of the South; also that the Statue of Liberty was originally conceived by Édouard de Laboulaye, a French abolitionist, who conceived of the idea of the Statue of Liberty and giving it to the United States as a gift, that it was originally conceived as an idea to celebrate the end of the Civil War and to celebrate abolition.

But over time, that meaning has been — even through the conception of the statue, right? The original conception of the statue actually had Lady Liberty breaking shackles, like a pair of broken shackles on her wrists, to symbolize the end of slavery. And over time, it became very clear that that would not have the sort of wide stream — or, wide mainstream support of people across the country, obviously this having been just not too long after the end of the Civil War, so there were still a lot of fresh wounds. And so they shifted the meaning of the statue to be more about sort of inclusivity, more about the American experience, the American project, the American promise, the promise of democracy, and sort of obfuscated the original meaning, to the point where even the design changed. And so they replaced the shackles with a tablet and the torch, and then put the shackles very subtly sort of underneath her robe. And you can — but the only way you can see them, these broken chains, these broken links, are from a helicopter or from an airplane.

And in many ways, I think that that is a microcosm for how we hide the story of slavery across this country, that these chain links are hidden, out of sight, out of view of most people, under the robe of Lady Liberty, and how the story of slavery across this country is very — as we see now, very intentionally trying to be hidden and kept from so many people, so that we have a fundamentally inconsistent understanding of the way that slavery shaped our contemporary society today.

AMY GOODMAN: Clint, before we end, you are an author, you’re a writer, you’re a teacher, and you are a poet. Can you share a poem with us?

CLINT SMITH: I’d be happy to. And so, when you’re a poet writing nonfiction, that very much animates the way that I approach the text. And so, this is part of the — this is an adaptation or an except from the end of one of my chapters, that originally began as a poem that I wrote when I was trying to think about some of these issues that I brought up.

[reading] Growing up, the iconography of the Confederacy was an ever-present fixture of my daily life. Every day on the way to school, I passed a statue of P.G.T. Beauregard riding on horseback, his Confederate uniform slung over his shoulder and his military cap pulled far down over his eyes. As a child, I did not know who P.G.T. Beauregard was. I did not know he was the man who ordered the first attack that opened the Civil War. I did not know he was one of the architects who designed the Confederate battle flag. I did not know he led an army predicated on maintaining the institution of slavery. What I knew is that he looked like so many of the other statues that ornamented the edges of this city, these copper garlands of a past that saw truth as something that should be buried underground and silenced by the soil.

After the war, the sons and daughters of the Confederacy reshaped the contours of treason into something they could name as honorable. We called it the Lost Cause. And it crept its way into textbooks that attempted to cover up a crime that was still unfolding; that told us that Robert E. Lee was an honorable man, guilty of nothing but fighting for the state and the people that he loved; that the Southern flag was about heritage and remembering those slain fighting to preserve their way of life. But, see, the thing about the Lost Cause is that it’s only lost if you’re not actually looking. The thing about heritage is that it’s a word that also means “I’m ignoring what we did to you.”

I was taught the Civil War wasn’t about slavery, but I was never taught how the declarations of Confederate secession had the promise of human bondage carved into its stone. I was taught the war was about economics, but I was never taught that in 1860 the 4 million enslaved Black people were worth more than every bank, factory and railroad combined. I was taught that the Civil War was about states’ rights, but I was never taught how the Fugitive Slave Act could care less about a border and spelled Georgia and Massachusetts the exact same way.

It’s easy to look at a flag and call it heritage when you don’t see the Black bodies buried behind it. It’s easy to look at a statue and call it history when you ignore the laws written in its wake.

I come from a city abounding with statues of white men on pedestals and Black children playing beneath them, where we played trumpets and trombones to drown out the Dixie song that’s still whistled in the wind. In New Orleans, there are over 100 schools, roads and buildings named for Confederates and slaveholders. Every day, Black children walk into buildings named after people who never wanted them to be there. Every time I would return home, I would drive on streets named for those who would have wanted me in chains.

Go straight for two miles on Robert E. Lee, take a left on Jefferson Davis, make the first right on Claiborne. Translation: Go straight for two miles on the general who slaughtered hundreds of Black soldiers who were trying to surrender, take a left on the president of the Confederacy who made the torture of Black bodies the cornerstone of his new nation, make the first right on the man who permitted the heads of rebelling slaves to be put on stakes and spread across the city in order to prevent the others from getting any ideas.

What name is there for this sort of violence? What do you call it when the road you walk on is named for those who imagined you under a noose? What do you call it when the roof over your head is named after people who would have wanted the bricks to crush you?

AMY GOODMAN: Clint Smith, author of the book How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America, speaking on Democracy Now! in 2021, the day after Juneteenth became a federal holiday.

What, to the white American, is the 19th of June?

One model for creating a new “season of critical patriotism” can be found in the Jewish High Holy Days.

Frederick Douglass, a writer, orator and the most well-known leader of the abolitionist movement. Photo © New York Historical Society / Bridgeman Images

June 19, 2024

By Robert P. Jones

(RNS) — On July 5, 1852, the Ladies Anti-Slavery Society of Rochester invited Frederick Douglass to give a speech on the 76th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The address became known by its central piercing question, “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?” Never one to sugarcoat his message, Douglass handed the good-willed ladies of Rochester a stinging indictment of the hypocrisy in white American celebrations of independence:

I am not included within the pale of [your] glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me.

This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day?

But Douglass also held out hope that the United States might yet live to be a nation worthy of its professed values. “Notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation,” he declared, “I do not despair of this country.” Even while exposing their blind spots and contradictions, Douglass thought it appropriate to honor the memory of the “statesmen, patriots and heroes…for the good they did, and the principles they contended for.”

Douglass was asking his white audience to hold their naive patriotism up next to his dissonant reality, not to cast shade but to light the road yet to be traveled.

RELATED: Should white Christians celebrate Juneteenth?

More than a century later, in the South of my childhood, the contradictions between the principles of equality enumerated in the Declaration of Independence and the glaring racial inequities permeating our community remained hidden in our Fourth of July celebrations.

On the Sunday closest to the holiday, our whites-only Southern Baptist congregation sang patriotic hymns, heard a sermon extolling the virtues of the nation and the promise of Western civilization, and on occasion began the service with a military color guard marching the American and Christian flags down the center aisle of the church. The soldiers parted like the Red Sea before the communion table and flowed up the blue carpeted steps, where they planted each flag in gleaming brass stands that flanked the pulpit.

The Fourth of July was our holiday, proudly celebrating our rightful inheritance of the American promised land.

But what, to the white American, is the 19th of June? Unlike most white Americans, I grew up with a vague awareness of Juneteenth (the name derives from a shortening of “June” and “nineteenth”), due to two coincidental factors. First, June 19th is my birthday. Second, I spent my preschool years in Texas, where the holiday was most prominently in the public eye. Leading up to my birthday, I occasionally saw signs around town announcing upcoming public Juneteenth celebrations. I was mildly fascinated, as young children are, with the juxtaposition of any other celebration with my birthday. But I was also told that this was a holiday Black people celebrated. Juneteenth was their holiday. It had nothing to do with us.

Of course, Juneteenth has everything to do with us. And on June 17, 2021, President Joe Biden made it official, signing legislation making June 19th a national holiday for all Americans.

But there are still obstacles blocking the acceptance and celebration of Juneteenth by white Americans. First, white Americans still have to grasp the significance of the historical event behind the holiday, which is admittedly complicated.

Unlike Martin Luther King Day, which honors the legacy of a person from recent history, who can be seen in television footage and engaged through a body of writing and speeches, Juneteenth commemorates an event from the messy final stages of the Civil War. While President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863, had technically freed enslaved people in Texas, this news had been both suppressed and ignored in this most westward state of the Confederacy for the final two and a half years of the war.

Juneteenth celebrates the date — June 19, 1865 — when U.S. Major General Gordon Granger issued General Order No. 3, which declared to the people of Texas that “all slaves are free.” Traditionally celebrated by African Americans, especially but not exclusively in Texas, Juneteenth is the oldest celebration of emancipation from slavery in the country. It was the final exorcism of the evil institution that had plagued our young nation for its first century and poisoned these lands since first European contact for nearly three centuries prior to that.

While at least some African Americans grew up celebrating Juneteenth with family picnics, concerts, special worship services, and storytelling, most white Americans had little awareness of, and almost no experience with, the holiday. While this disconnect creates some hurdles for the holiday being integrated broadly into American culture, it also presents an opportunity.

In a recent conversation, my good friend the Rev. Jacqui Lewis, the innovative senior minister of Middle Collegiate Church in New York City, suggested that because of its proximity to Independence Day, both temporally and conceptually, our newest federal holiday has powerful potential to help rehabilitate the 4th of July from the jingoistic Christian nationalism it all too often evokes. I’ve been thinking about that insight a lot over the past few days.

As we head toward my birthday and Juneteenth this year, and as I’ve been wrestling with my own uncertainty about how to mark the holiday, I’ve realized that one model for creating what we might call a new “season of critical patriotism” can be found in the Jewish High Holy Days.

Among the many gifts of being in an interfaith marriage is the ongoing invitation to experience and learn from a tradition that is not your own. As I’ve participated in this annual season of reflection over the last 20 years, I’ve been moved by the power of the moral space that opens in the ten days between a celebration of the promise of the new year on Rosh Hashanah and lament over the failings of the past at Yom Kippur. The sweetness of apples, honey, and kugel foreshadows repentance, fasting, and atonement. Like binary stars, these holidays orbit one another, generating a contemplative space between them known as the “days of awe.”

The period of 15 days that span the space between Juneteenth and Independence Day could similarly function as an enduring season of critical patriotism for our time. Alongside the celebratory fireworks and other well-established practices surrounding the 4th of July, we could develop new rituals that include the creative interplay of lament and celebration, reckoning and repair, truth-telling and dreaming.

Borrowing from the High Holidays model, we could conceptualize this season as the “days of freedom and equality,” anchored by the Juneteenth proclamation that all are free and the Independence Day declaration that all are equal. We could also embrace a conviction that is deeply engrained in Judaism, Christianity, and indeed most religious traditions — that no people can live with integrity into the future if they cannot face failures to live up to their principles in the past.

Such a reconfiguration of Independence Day is also well-suited to help us cope with a dilemma created by our current era of historical reckoning. Fairy-tale narratives of impossible national innocence are thankfully no longer credible, particularly to nonwhite or non-Christian Americans, or, to most Americans under the age of 40. But in the harsh light of historical indictment, we also risk losing sight of our better angels and noble principles still waiting to be realized.

RELATED: Juneteenth isn’t about the past. It’s about our future.

Conceptualizing the 19th of June and the 4th of July together, in a creative mutual orbit where each is held by the gravitational force of the other, can help us develop rituals and stories that are honest about our country’s failings while also being hopeful about its possibilities.

Beginning this season with Juneteenth can help us — especially white Americans — recalibrate Independence Day, as Douglass admonished his fellow Americans to do, as an opportunity to conduct a more forthright assessment of America as a work in progress. Such a season of critical patriotism would be one all of us could embrace.

(Robert P. Jones is president and founder of the Public Religion Research Institute and the author, most recently, of “The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy and the Path to a Shared American Future.” This article first appeared on his Substack newsletter. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

Juneteenth celebrated in Emancipation Park, Houston, Texas in 1880

Juneteenth was a people’s holiday with deep meaning for the descendants of enslaved people. But the declaration of an official federal holiday has turned it into an opportunity for corporate exploiters and cynical politicians to show pretend concern for Black people. At best Juneteenth provides a history lesson and an opportunity for much needed political education.

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.” General Order Number 3, June 19, 1865

The fact that members of the United States Senate voted unanimously to make Juneteenth a federal holiday proved that the commemoration is of no political value. Turning what was a peoples’ celebration into an occasion for opportunism and window dressing has actually damaged the cause of Black liberation and the understanding of history.

On June 19, 1865 Union soldiers arrived in Galveston, Texas and issued General Order Three, a declaration that slavery had ended. The fact that this event occurred two months after the Civil War ended took on an understandably mythic quality, including a belief that the news had been deliberately kept from enslaved people, or that the person carrying the message had been killed.

In reality, enslaved Texans were well aware that the war had ended. But they also knew that the absence of federal troops who could enforce the law made any legalities moot. They knew better than anyone else that the people who forced them to labor without compensation would not end their system unless they were forced to do so.

Juneteenth was widely celebrated in Texas and other southern states while the rest of the country was largely unaware of their special commemoration. Of course the day had meaning to those people descended from the enslaved in those regions and they gave the day significance in their own way. Unfortunately Juneteenth came to be more widely known and now the serious and the scoundrels alike lay claim to what should be an important occasion.

The governmental imprimatur has given way to foolishness, insult, and confused reactions. A children’s museum was condemned for serving a Juneteenth watermelon salad . The stereotypical connection of Black people with watermelon was lost on an institution committed to cultural education. Not to be outdone, Walmart sold Juneteenth ice cream which like the watermelon salad was quickly removed after protest. Then again, the business of America is business. No one should be surprised that what should be a solemn remembrance is now commodified.

But anger about ice cream and watermelon is misplaced. Corporations, avaricious banks, and cynical politicians are all claiming to be Juneteenth believers. Of course they all use Juneteenth to pretend they aren’t what they actually are, and that is a sign that Juneteenth itself is problematic.

What exactly is being celebrated on June 19? Juneteenth could be a history lesson which explained that Abraham Lincoln was not the great emancipator. Everyone should know that the Emancipation Proclamation freed enslaved people only in states like Texas which were in rebellion against the federal government, but which were safely able to continue the peculiar institution until they were forced to end it. Lincoln tied emancipation to colonization, the plan to send Black people out of the country and he actually established one such colony in Haiti.

The Civil War is rarely taught properly. The well documented struggle for liberation is left out of the story. The enslaved people who fled to Union lines whenever they were able forced Lincoln to state that ending slavery was the object of the conflict. He only reluctantly agreed to establish the United States Colored Troops, who were more invested in victory than any other group in the country. Of course, he never gave up on his dream of an all white country. Shortly before his assassination he still expressed a desire to send Black people away and to compensate the Confederacy for its lost free labor.

Instead of pointing out these well documented facts, Juneteenth is an amorphous celebration of Black people. The best it can accomplish is to point out that freedom itself is ever amorphous in this country. Enslavement was soon followed by lynch law terrorism, the sharecropping system, and the convict leasing system. Mass Black incarceration at the end of the 20th century brought about a new system of free labor, as vicious as that in the Jim Crow south.

The General Order itself shows the illusory nature of freedom for Black people. It warned the newly freed not to “collect at military posts” and not to be idle. Of course, they were forced to work hard for nothing. An allowance for temporary idleness should have been permitted, but this directive is yet another reason for serious discussion and study.

It is not surprising that Black people want validation but that desire is all too often misplaced. Validation comes when the past is remembered correctly and when real victories are achieved. It was sad to witness people who thought Juneteenth ice cream would have been acceptable if it were sold by a Black owned business. Of course liberation won’t come from Black capitalism either. Perhaps that is something to focus on instead of getting a day off from work while wishing that white people didn’t get the same consideration.

Juneteenth won unanimous approval in the Senate and only a handful of objections from republicans in the House of Representatives. This widespread acceptance is actually proof that the effort was misguided. On the one hand, we are told to hate the likes of republican leaders like Mitch McConnell, but suddenly celebrate when they toss a bone. When Joe Biden signed the law which made Juneteenth a federal holiday his remarks were replete with platitudes about the sin of slavery, the redemption of American progress, the importance of HBCUs and home ownership, and just for good measure, a plea to be vaccinated against covid. The laundry list of topics was further proof that a people’s holiday has become meaningless.

Juneteenth’s only value is if it becomes a day of serious study and political education. That process can start with learning why “Jim Crow Joe” Biden received 90% of the Black vote or why the 2020 rebellions after George Floyd’s murder created a need for the state to placate Black people, if only symbolically. The Civil War is a perfect starting point for this practice. If there is a day off it should be used wisely and well. In the future, all people’s holidays should stay that way. Perhaps they should be kept secret so that commemorations aren’t used to give legitimacy to bad actors. It is too late for Juneteenth, but the hard lesson can be the beginning of something far more valuable.

No comments:

Post a Comment