Proletkult Manifestos

Updated: Apr 22

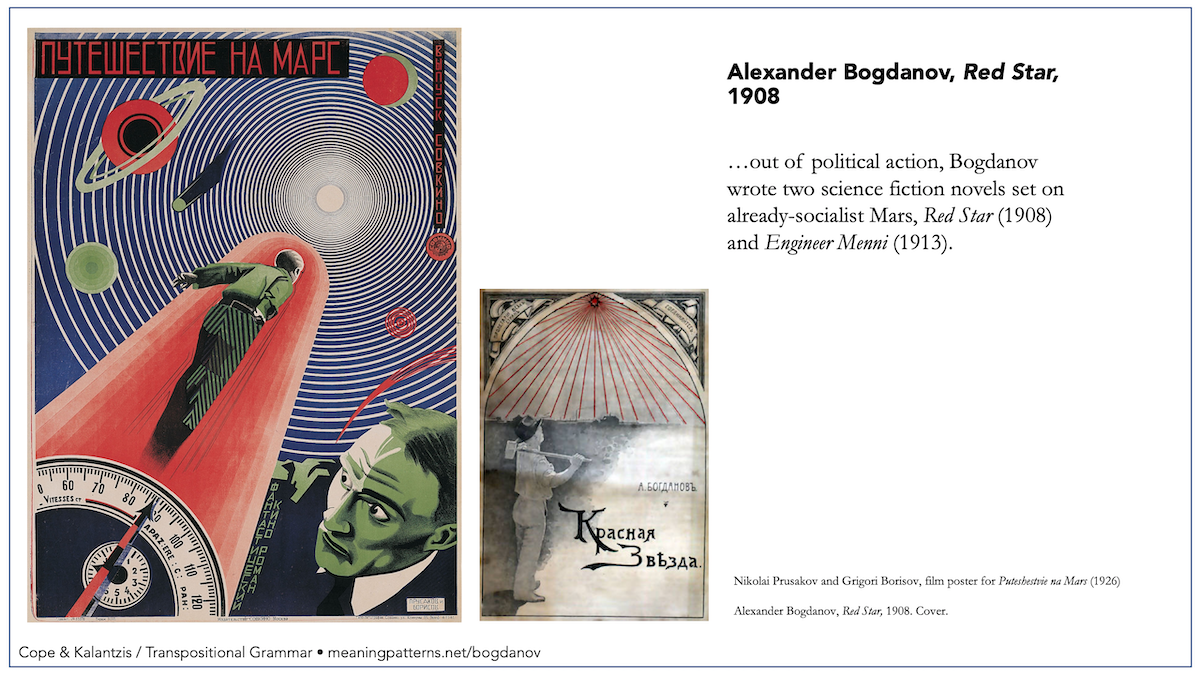

A. Bogdanov " The Proletariat and Art»

"The earliest germs of art are the love song of many animals and of man, and the labor song of man. The first is a means of organizing the family, marriage, and the second is an instrument of organizing labor. Later there was a battle song. It was a means to unite the combat team in the unity of mood." (p. 117)

"The ancient myth was even at the same time the embodiment of both science and poetry: it gave people in living images of the word what science now gives in abstract concepts. "(p. 118)

"What is the difference between science and art? The fact that art organizes experience in living images, and not in abstract concepts. Thanks to this, its area is wider: it can organize not only people's ideas, their knowledge and thoughts, but also their feelings, their moods." (p. 118)

"Different arts in different ways connect people in the unity of mood, educate and socially shape their relationship to the world and to other people. "(p. 118)

"Art is not only broader than science, it has hitherto been stronger than science as a tool for organizing the masses, because the language of living images was closer and more understandable to the masses. It is clear that the art of the past cannot in itself organize and organize the proletariat as a special class with its own tasks and its own ideal. Art is religious-feudal, authoritarian, introduces people to the world of power, submission, educates the masses in submission, humility and blind faith. Bourgeois art, having as its constant hero a person who is fighting for himself and his own, educates an individualist." (p. 118-119)

"Faust is a brilliant work of the secret adviser W. Goethe, a bourgeois aristocrat. It would seem that there is nothing valuable in it for the proletariat, but you know that our thinkers often quote from Faust. What is the inner meaning of this work, what is its "artistic idea", i.e., from our point of view, its organizational tasks? In it, ways are found for such an arrangement, such an organization of the human soul, so that complete harmony is achieved between all its forces and abilities. Faust is a representative of the human soul, always searching, always restless, longing for harmony. " (p. 120)

"More than 2000 years ago, a statue of the goddess was created, which gathered a lot of people in the temple, uniting it in one, even if alien to us, mood. This was the Venus Urania-the celestial Venus, the representative of pure love, as it was understood by the ancients-the harmonious love of the spiritual and physical. The temple was the center of communication, the goddess the center of the temple. Consequently, it was the center of the collective organization. It reflected an alien world in a calm, majestic, far from effort, tension and impulse, but in real, divine beauty." (p. 121)

"And folk poetry?.. Take the epics about Ilya Muromets. This is the embodiment in one hero of the collective strength of the peasantry of feudal Russia, the true builder and defender of our land. Let it be an individualistic image, otherwise the peasantry is not able to express its soul, and even now it is not able to express its collective strength in one person. "(p. 122)

"Comrades, we need to understand: we live not only in the collective of the present, we live in the cooperation of generations. This is not class cooperation, it is the opposite of it. All the workers, all the leading fighters of the past — are our comrades, no matter what class they belong to. "(p. 122-123)

"So, comrades, we need the art of the past, but just like the science of the past, in a new understanding, in a critical interpretation of a new, proletarian thought.

This is a matter for our critics. It must go hand in hand with the development of proletarian art itself, helping it with advice and interpretation, and guiding it in the use of the artistic treasures of the past. These treasures it must hand over to the proletariat, explaining to them all that is useful and necessary for them, and what is lacking in them for them. Artistic talent is individual, but creativity is social: it comes from the collective and returns to it, and serves it vitally. And the organization of our art must be built on comradely cooperation, just as the organization of our science is. " (p. 123)

[1]

A. Gastev " Contours of Proletarian culture»

"The definition of proletarian culture must be approached with the greatest caution. They say that this is, first of all, the culture of work. But labor has existed since the creation of the world. This is the psychology of hired labor. But even here it is difficult to distinguish between slave psychology and proletarian psychology. Psychology of struggle, insurrection, and revolution... "

"After all, the 'Soviet' constitution is nothing but a democracy with electoral restrictions for the propertied classes, and, moreover, the Soviets are a political bloc of the proletariat, the peasant poor, and even the 'middle peasants'. Somewhere far away, somewhere up from these temporary formations, one must go in order to probe the rising culture of the proletariat."

"For the new industrial proletariat, for its psychology, for its culture, first of all, industry itself is characteristic. Buildings, pipes, columns, bridges, cranes and all the complex constructiveness of new buildings and enterprises, the catastrophism and inexorable dynamics – this is what permeates the everyday consciousness of the proletariat. The whole life of modern industry is steeped in movement, disaster, embedded at the same time in the framework of organization and strict regularity. Catastrophe and dynamics, bound by a grandiose rhythm, are the main, overshadowing moments of proletarian psychology."

"The proletariat, gradually broken down by the new industry into certain 'types', 'types', into people of a certain 'operation', into people of a certain gesture, on the other hand, absorbs into its psychology all the grandiose assembly of the enterprise that passes before its eyes. This is mainly the open and visible assembly of the factory itself, the sequence and subordination of operations and fabrications, and finally the general assembly of the entire production, which is expressed in the subordination and control of one operation to another, of one "type" to another, and so on."

"The psychology of the proletariat here is already turning into a new social psychology, where one human complex works under the control of another, and where often the "controller" in the sense of labor qualifications is below the controlled and very often personally completely unknown. This psychology reveals a new working collectivism, which manifests itself not only in the relationship of man to man, but also in the relationship of integral groups of people to integral groups of mechanisms. Such collectivism can be called mechanized collectivism."

"In the face of the proletariat, we have a growing class that simultaneously deploys the living labor force, the iron mechanics of its new collective, and a new mass engineering that turns the proletariat into an unprecedented social automaton."

"We do not want to be prophets, but, in any case, we must associate with proletarian art a stunning revolution of artistic techniques. In particular, the artists of the word will have to solve not such a task as the futurists set themselves, but much higher. If futurism has put forward the problem of" word-making", then the proletariat will inevitably put it forward too, but it will not reform the word itself grammatically, but it will risk, so to speak, the technicalization of the word. The word taken in its everyday expression is clearly no longer sufficient for the workers ' and production goals of the proletariat."

"We are going to an unprecedented objective demonstration of things, mechanized crowds and a stunning, open grandiosity that knows nothing intimate and lyrical."

[2]

A. Bogdanov " The Ways of proletarian Creativity»

"Creativity, everything — technical, socio-economic, everyday, scientific, artistic-is a kind of work, and in the same way it is composed of organizing (or disorganizing) human efforts. This is nothing but labor, the product of which is not a reproduction of the finished model, it is something "new"." (p. 192)

"Creativity is the highest, most complex type of work. Therefore, his methods are based on the methods of labor. All methods of work — and with it, creativity-lie within the same framework. Its first phase is the combining effort, the second is the selection of its results, the elimination of the unsuitable, the preservation of the suitable. In the "physical" work, material things are combined, in the "spiritual" — images; but, as the latest psychophysiology shows, the nature of the efforts of combining and selecting is the same — neuromuscular." (p. 192-193)

"Creativity combines materials anew, not according to the usual pattern, which leads to a more complex, more intense selection. The combination and selection of images is incomparably easier and faster than material things. Schiller put it in words: "Thoughts easily get along in the mind, but bodies collide sharply in space." "Therefore, creativity often proceeds in the form of "spiritual" work, but not exclusively. "(p. 193)

"Human labor, always relying on collective experience and using collectively developed means, is always collective in this sense, no matter how narrowly individual its goals and its external, direct form are in particular cases (i.e., even when it is the work of one person, and only for oneself). "(p. 194)

"The methods of proletarian creativity have their basis in the methods of proletarian labor, that is, the type of work that is characteristic of the workers of the latest large-scale industry.

Features of this type: 1) the combination of elements of "physical" and "spiritual" labor; 2) transparent, not hidden or disguised collectivism of its very form. The first depends on the scientific nature of the latest technology, in particular on the transfer of the mechanical side of effort to the machine: the worker is increasingly becoming the " leader "of the iron slaves, and his work is increasingly reduced to" spiritual " efforts — attention, consideration, control, initiative, while the role of muscular tension is relatively reduced. The second depends on the concentration of labor in mass cooperation and on the convergence of specialized types of labor by the power of machine production, which increasingly transfers the direct, physical specialization of workers to machines." (p. 194-195)

"In science and philosophy, Marxism was the embodiment of both the monism of the method and the conscious-collectivist tendency. Further development on the basis of the same methods should develop a universal organizational science that monistically unites the entire organizational experience of humanity in its social work and struggle." (p. 195-196)

"In the field of artistic creativity, the old culture is characterized by uncertainty and unconsciousness of methods ("inspiration", etc.), their isolation from the methods of labor practice, from the methods of creativity in other areas. Although the proletariat is only making its first steps here, the general tendencies peculiar to it are already clearly outlined. Monism manifests itself in the desire to merge art with working life, to make art an instrument of its active and aesthetic transformation along the entire line. Collectivism, at first spontaneous, and then increasingly conscious, appears vividly in the content of artistic works, and even in the form of artistic perception of life, illuminating the image not only of human life, but also of the life of nature: nature as a field of collective labor; its connections and harmonies, as the germs and prototypes of the organization of the collective." (p. 196)

"Conscious collectivism transforms the whole meaning of the artist's work, giving it new incentives. The former artist saw in his work the identification of his individuality; the new one will understand and feel that in and through him a great whole — the collective-is creating." (p. 197)

"The awareness of collectivism, by deepening the mutual understanding of people and the connection of feeling between them, will make possible an incomparably wider development of direct collectivism in creativity, i.e., direct cooperation of many people in it, even to the mass. "(p. 197)

"The object of production technology is nature, its natural forces. The meaning of technical techniques is the subordination of these forces, the conservation and accumulation of human energy.

The object of the ideological technique is the living experience of the collective The meaning of its techniques is the adaptation of this experience to the tasks and needs of the collective, its organization in accordance with them." (p. 197-198)

"In the art of the past, as in its science, there are many hidden elements of collectivism. By revealing them, proletarian criticism makes it possible to creatively perceive the best works of the old culture, in a new light and with a huge enrichment of their value. This is the way to acquire the world cultural heritage that legally belongs to the proletariat. "(p. 199)