The True Reason For So Much Hunger in The World Is Probably Not What You Think

(artur carvalho/Getty Images)

GISèLE YASMEEN, THE CONVERSATION

13 APRIL 2022

Nearly one in three people in the world did not have access to enough food in 2020. That's an increase of almost 320 million people in one year and it's expected to get worse with rising food prices and the war trapping wheat, barley and corn in Ukraine and Russia.

Climate change related floods, fires and extreme weather, combined with armed conflict and a worldwide pandemic have magnified this crisis by affecting the right to food.

Many assume world hunger is due to "too many people, not enough food." This trope has persisted since the 18th century when economist Thomas Malthus postulated that the human population would eventually exceed the planet's carrying capacity. This belief moves us away from addressing the root causes of hunger and malnutrition.

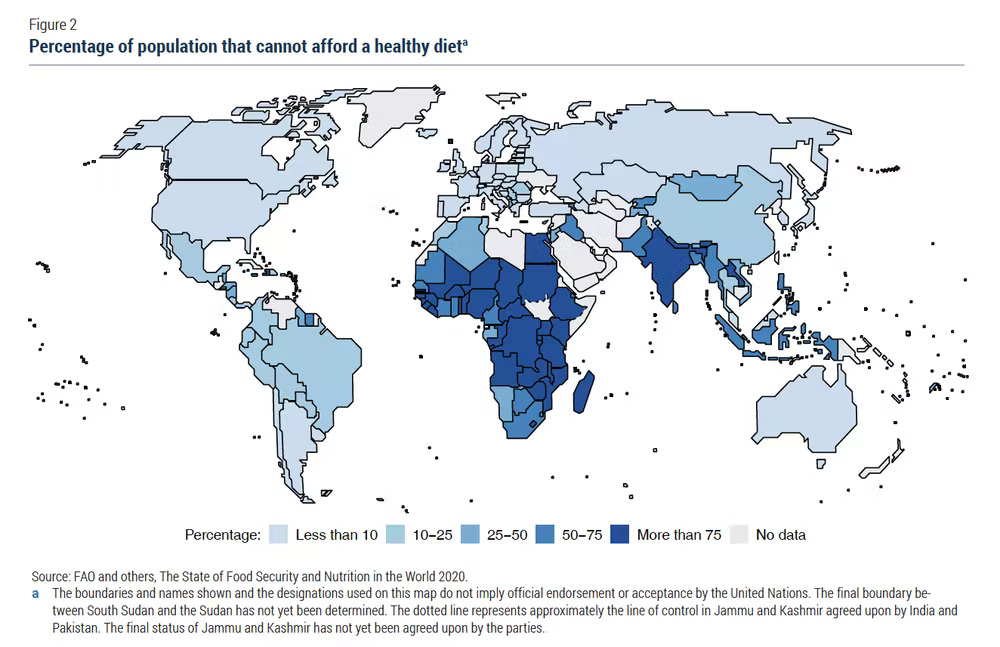

In fact, inequity and armed conflict play a larger role. The world's hungry are disproportionately located in Africa and Asia, in conflict-ridden zones.

As a researcher who has been working on food systems since 1991, I believe that addressing root causes is the only way to tackle hunger and malnutrition. For this, we need more equitable distribution of land, water and income, as well as investments in sustainable diets and peace-building.

But how will we feed the world?

The world produces enough food to provide every man, woman and child with more than 2,300 kilocalories per day, which is more than sufficient. However, poverty and inequality – structured by class, gender, race and the impact of colonialism – have resulted in an unequal access to Earth's bounty.

Half of global crop production consists of sugar cane, maize, wheat and rice – a great deal of which is used for sweeteners and other high-calorie, low-nutrient products, as feed for industrially produced meat, biofuels and vegetable oil.

The global food system is controlled by a handful of transnational corporations that produce highly processed foods, containing sugar, salt, fat and artificial colors or preservatives. Overconsumption of these foods is killing people around the world and taxing healthcare costs.

Nutrition experts say that we should limit sugars, saturated and trans fats, oils and simple carbohydrates and eat an abundance of fruits and vegetables with only a quarter of our plates consisting of protein and dairy. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change also recommends a move toward sustainable healthy diets.

A recent study showed that overconsumption of highly processed foods – soft drinks, snacks, breakfast cereals, packaged soups and confectionery items – can lead to negative environmental and health impacts, such as Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disorders.

Steering the world away from highly processed foods will also lessen their negative impacts on land, water and reduce energy consumption.

We live in a world of plenty

Since the 1960s, global agricultural production has outpaced population growth. Yet the Malthusian theory continues to focus on the risk of population increases outstripping the Earth's carrying capacity, even though global population is peaking.

Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen's study of the Great Bengal Famine of 1943 challenged Malthus by demonstrating that millions died of hunger because they didn't have the money to buy food, not due to food shortages.

In 1970, Danish economist Ester Boserup also questioned Malthus's assumptions. She argued that rising incomes, women's equality and urbanization would ultimately stem the tide of population growth, with the birthrate, even in poor countries, dropping to at or below replacement levels.

Food – like water – is an entitlement, and public policy should stem from this. Unfortunately, land and income remain highly unevenly distributed, resulting in food insecurity, even in wealthy countries. While land redistribution is notoriously difficult, some land reform initiatives – like the one in Madagascar – have been successful.

The role of war in hunger

Hunger is aggravated by armed conflict. The countries with the highest rates of food insecurity have been ravaged by war, such as Somalia. More than half of the people who are undernourished and almost 80 percent of children with stunted growth live in countries struggling with some form of conflict, violence or fragility.

UN Secretary General António Guterres has warned that the war in Ukraine puts 45 African and least developed countries at risk of a "hurricane of hunger," as they import at least a third of their wheat from Ukraine or Russia. According to the New York Times, the World Food Program has been forced to cut rations to nearly four million people due to higher food prices.

What works, ultimately, are adequate social protection floors (basic social security guarantees) and rights based "food sovereignty" approaches that put communities in control of their own local food systems. For example, the Deccan Development Society in India assists rural women by providing access to nutritious food and other community supports.

To address food insecurity, we must invest in diplomacy by coordinating humanitarian, development and peacekeeping activities to avoid and curtail armed conflicts. Poverty reduction is part of peace building as rampant inequalities serve as tinderboxes for aggression.

Protecting our ability to produce food

Climate change and poor environmental management have put collective food production assets including soil, water and pollinators in peril.

Several studies over the past 30 years have warned that soil and water contamination from high concentrations of toxins such as pesticides, dwindling biodiversity and disappearing pollinators could further affect the quality and quantity of food production.

Livestock, crop production, agricultural expansion and food processing account for a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, one-third of all food produced is lost or goes to waste, so tackling this travesty is also paramount.

Reducing food loss and waste will help reduce environmental impacts of the food system, as will transitioning to healthier, sustainably produced diets.

Food, health and environmental sustainability

Food is an entitlement and should be viewed as such, not framed as an issue of population growth or inadequate food production. Poverty and systemic inequalities are the root causes of food insecurity as is armed conflict. Keeping this idea central in discussions about feeding the world is essential.

We need policies that support healthy and sustainably produced, balanced diets to address chronic diet-related disease, environmental issues and climate change.

We need more initiatives that enable equitable distribution of land, water and income globally.

We need policies that address food insecurity through initiatives like rights-based food sovereignty systems.

In areas affected by conflict and war, we need policies that invest in diplomacy by coordinating humanitarian, development and peacekeeping activities.

These are the key pathways to recognize that "food is the single strongest lever to optimize human health and environmental sustainability on Earth."

Gisèle Yasmeen, Senior Fellow, School of Public Policy and Global Affairs, University of British Columbia.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.