Briley Lewis

Tue, August 22, 2023

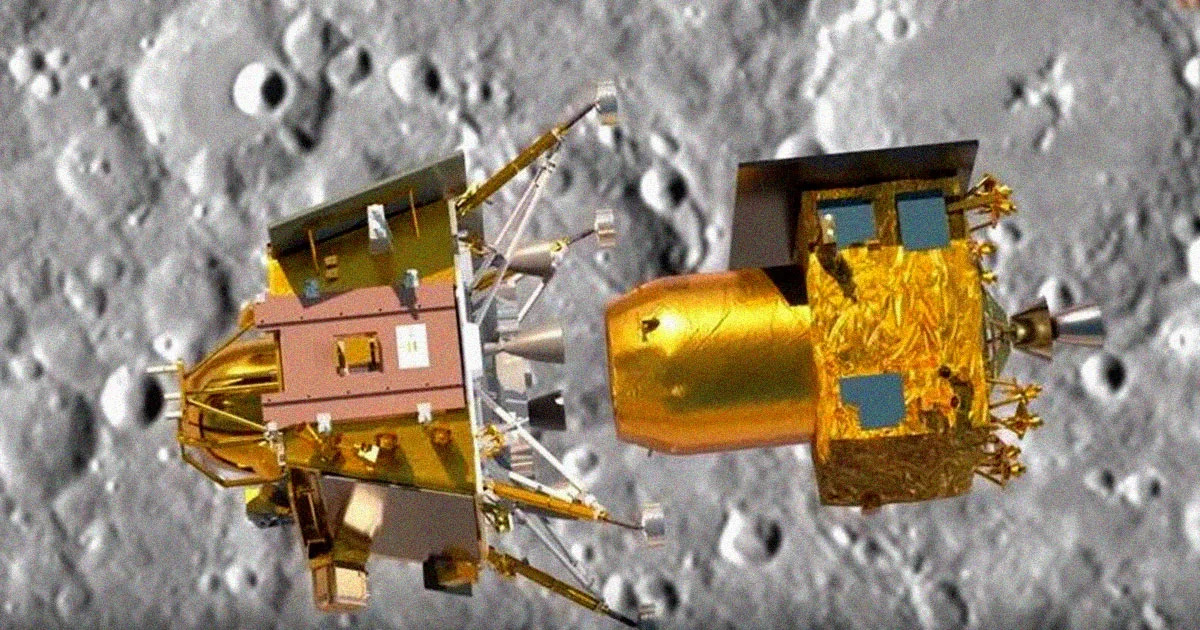

The Chandrayaan-3 lander prior to its launch.

This could be a record week for space exploration—despite the obliterating crash of Russia’s lunar spacecraft on Sunday. The Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) will attempt to land on the moon on August 23 with the Chandrayaan-3 mission. If successful, India will be only the fourth country to successfully place a probe on the moon, and the first to land at the lunar south pole.

The first Soviet and American soft landings on the moon happened all the way back in the 1960s, at the dawn of the Space Race. But it’s not easy to deposit a lunar lander—since those early successes, China has been the sole country to join Russia and the US in this feat.

“Very few countries have landed on anything. It’s just really hard, and everything has to work just about perfectly,” says Dave Williams, a planetary scientist who archives data of the moon at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

To start, spaceflight is a huge engineering challenge, and the moon is a particularly tricky target. Unlike Earth or Mars, our satellite has no atmosphere, so there’s nothing natural to slow down a spacecraft—no air for parachutes or gliders to use. The only way to get to the surface without crashing is a controlled descent, in which rockets lower the probe all the way down. Plus, the rocket engines must shut off at a precise moment so the craft doesn’t bounce back up off the lunar surface.

Making matters worse, although the moon doesn’t have oceans or cities, it still has plenty of hazards—namely, rocks and craters. Spacecraft have to navigate this terrain mostly on their own. The moon is far away enough from Earth command centers that a lander must be pre-programmed to do what it needs to for a safe landing.

This isn’t India’s first visit to the moon. The country’s lunar program began back in 2008, with a lunar orbiter and impactor in the Chandrayaan-1 mission. Chandrayaan-1 “played a vital role in raising awareness of space science among the general public,” says University of Florida astronomer Pranav Satheesh. “Many students, including myself, were inspired to pursue careers in space science and astronomy upon witnessing the success of ISRO's programs.”

India made its first attempt at a soft landing with the Chandrayaan-2 mission in 2019. Unfortunately, that lander, named Vikram after the pioneering physicist Vikram Sarabhai, failed in the very last stages of its descent, crashing into the lunar surface. NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter later spotted debris from Vikram’s crash as bits of metal strewn across the lunar landscape. The Chandrayaan-2 orbiter remained operational, however, and it continues to collect data in support of the current lunar landing attempt.

Chandrayaan-3’s journey so far has been right on track. "Excitement about this mission is definitely palpable across Indian news media, WhatsApp chats, and even in everyday conversations for a lot of folks there," says Pratik Gandhi, an astronomer at the University of California, Davis.

It entered lunar orbit on August 5, separated from its propulsion system on August 17, and even snapped a few teaser pics of the moon on August 18. As the lander descends to the moon in the coming days, the most dangerous moment is likely the landing’s final step: the fine braking phase. “The lander must kill all of its velocity and enter a hover state at about a kilometer above the lunar surface, at which point it must also decide in 12 seconds if it’s above its desired landing region or not and proceed with the touchdown accordingly,” explains science journalist Jatan Mehta. Russia’s Luna-25 probe, on the other hand, failed much earlier in its journey—which may be a sign of poor manufacturing or a lack of testing.

When the Indian lander touches down, it should only be moving at about 4 miles per hour. But only the slightest deviations separate a crash landing from a controlled one. “The moon’s gravity, even though it is only about one-sixth of Earth’s, is still more than enough to destroy a spacecraft if it isn’t slowed down,” says Williams.

If Chandrayaan-3 safely reaches the moon, it has some exciting science investigations in store. Unlike any lander to come before, Chandrayaan-3 is targeting the moon’s south pole, where astronomers think there are deposits of water. Water is a crucial resource for future longer-term space exploration, both for astronauts to drink and for use as rocket fuel.

Chandryaan-3’s lander, also called Vikram, is carrying a small rover named Pragyan. Pragyan is only about 50 pounds—the weight of a medium-sized Goldendoodle—and will roam the lunar surface for about two weeks. It’s equipped with two spectrometers, which can measure the composition of rocks and soil, providing scientists with crucial information about this never-before-explored region of the moon.

The lunar southlands are also a key target for future installments in NASA’s Artemis program, paving the way for semi-permanent human habitation on our nearest celestial neighbor. In June 2023, India signed on to the Artemis Accords, an agreement for cooperation between countries in space exploration. Japan, another signatory of the accords, even has a rover in the works with India, with the goal of drilling into the lunar south pole in search of more water. All of these plans will have a better chance at fruition if India successfully lands on the moon.

“That India is one of the few countries to be able to build lunar landers means Chandrayaan-3’s success will be a critical part of being able to truly sustain the current global momentum for a return to the moon,” says Mehta. As more nations try to land on the moon, lessons from success—and failures—should help improve each next attempt.

Tune in to watch the Chandrayaan-3 landing on the ISRO’s YouTube channel starting at 7:57 a.m. Eastern time/4:57 a.m. Pacific (5:27 p.m. India Standard Time) on August 23. The actual landing is scheduled to take place approximately 37 minutes later. Within seconds, we should know if the lander has safely touched down on the moon.

Andrew Jones

Mon, August 21, 2023

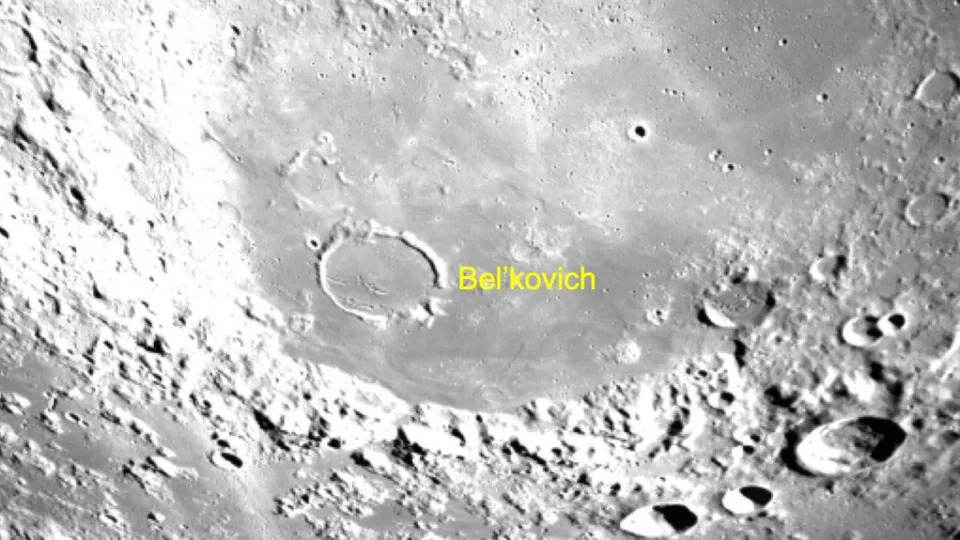

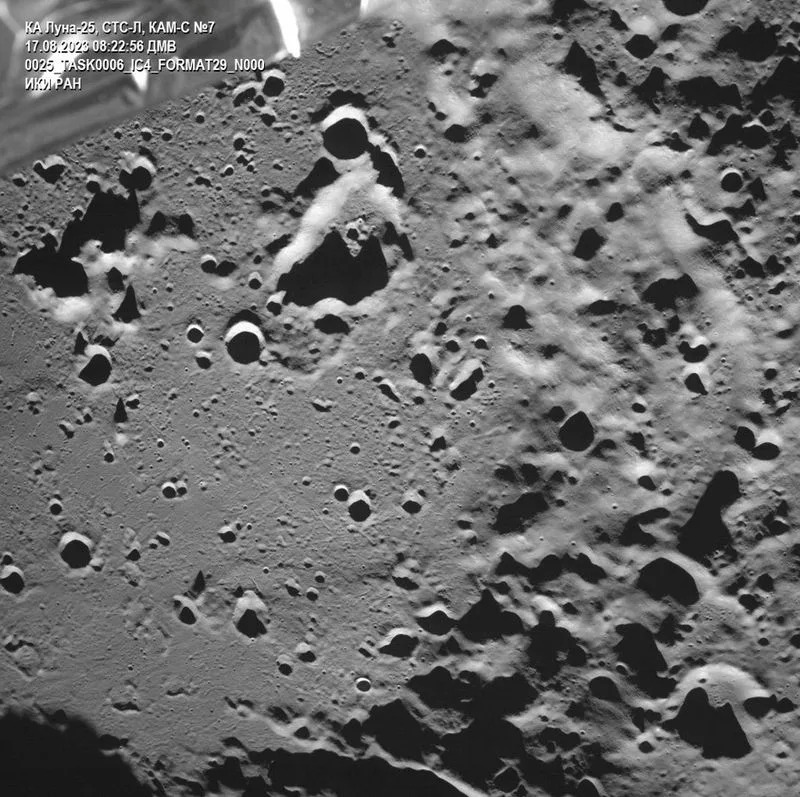

closeup of the moon's surface, showing numerous craters

India's Chandrayaan-3 probe has been testing out its landing optics by imaging the far side of the moon.

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) released the images via X, the social media service formerly named Twitter, on Monday (Aug. 21).

The series of four Chandrayaan-3 images were taken on Saturday (Aug. 19) and show a range of geological features, including vast impact craters that cast varying degrees of shadows and lunar mare, or "seas" of cooled moon lava.

Related: Chandrayaan-3: A guide to India's third mission to the moon

closeup of the moon's surface, showing numerous craters

The far side of the moon never faces Earth because of "tidal locking," with our planet's gravity having slowed the rotation of its natural satellite over billions of years. The moon completes one rotation on its axis in the same amount of time it takes to orbit Earth.

The new images were captured by Chandrayaan-3's Lander Hazard Detection and Avoidance Camera (LHDAC). The camera is designed to help guide the mission's Vikram lander to a safe landing site during its descent onto the lunar surface.

"This camera that assists in locating a safe landing area — without boulders or deep trenches — during the descent is developed by ISRO at SAC," ISRO stated.

Chandrayaan-3 is scheduled to land around 8:34 a.m. EDT (1234 GMT and 18:04 India time) on Wednesday (Aug. 23). The spacecraft is targeting a landing site at 69.37 degrees south latitude and 32.35 degrees east longitude, near the lunar south pole. A live telecast of the attempt will begin around 45 minutes earlier, according to ISRO. You can watch that webcast here at Space.com.

Chandrayaan-3 is now aiming to be the first probe ever to make a soft landing in the vicinity of the lunar south pole. It was considered by many to be in a race with Russia's Luna-25 lander, but the latter spacecraft crashed into the moon following a failed orbital maneuver on Saturday (Aug. 19).

RELATED STORIES:

— India launches historic Chandrayaan-3 moon rover to land at the lunar south pole

— What's next for India's Chandrayaan-3 moon rover mission?

— Latest news about India's space program

India's first attempt to land on the moon came in 2019. The Chandrayaan-2 lander experienced errors during the latter part of its descent and made a hard impact with the lunar surface. ISRO stated on Monday that the Chandrayaan-3 lander established two-way communications with the orbiter from the Chandrayaan-2 mission.

Chandrayaan-3 launched into a highly elliptical Earth orbit on July 14, before gradually raising its orbit and firing itself into a lunar trajectory. It entered lunar orbit on Aug. 5 before conducting a series of engine burns to circularize its orbit.

The Vikram lander, which also carries a small rover named Pragyan, separated from the mission's propulsion module on Aug. 17. If they land successfully, Vikram and Pragyan will spend almost a full lunar daytime (roughly 14 Earth days) conducting science experiments on the moon.

A soft landing would make India only the fourth country, after the United States, the former Soviet Union and China, to achieve such a feat. But that list could soon get bigger. Japan's Smart Lander for Investigating Moon (SLIM) is scheduled to lift off on a H-2A rocket on Aug. 26 from Tanegashima Space Center

By Nivedita Bhattacharjee and Joey Roulette

Tue, August 22, 2023

BENGALURU/WASHINGTON (Reuters) - The space race India aims to win this week by landing first on the moon's south pole is about science, the politics of national prestige and a new frontier: money.

India's Chandrayaan-3 is heading for a landing on the lunar south pole on Wednesday. If it succeeds, analysts and executives expect an immediate boost for the South Asian nation's nascent space industry.

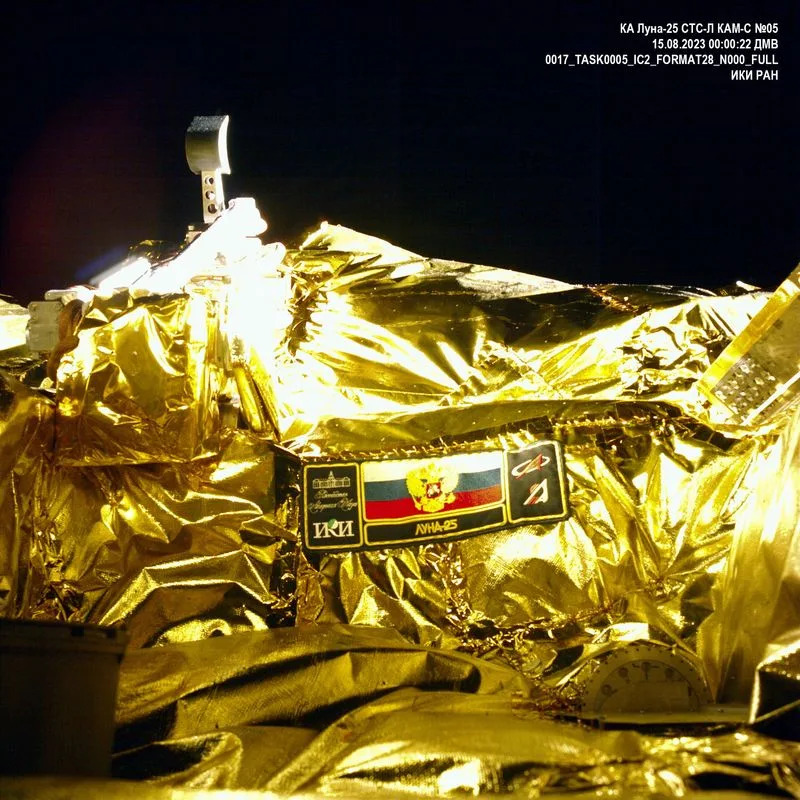

Russia's Luna-25, which launched less than two weeks ago, had been on track to get there first – before the lander crashed from orbit, possibly taking with it the funding for a successor mission, analysts say.

The seemingly sudden competition to get to a previously unexplored region of the moon recalls the space race of the 1960s, when the United States and the Soviet Union competed.

But now space is a business, and the moon's south pole is a prize because of the water ice there that planners expect could support a future lunar colony, mining operations and eventual missions to Mars.

With a push by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, India has privatised space launches and is looking to open the sector to foreign investment as it targets a five-fold increase in its share of the global launch market within the next decade.

If Chandrayaan-3 succeeds, analysts expect India's space sector to capitalise on a reputation for cost-competitive engineering. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) had a budget of around just $74 million for the mission.

NASA, by comparison, is on track to spend roughly $93 billion on its Artemis moon programme through 2025, the U.S. space agency's inspector general has estimated.

"The moment this mission is successful, it raises the profile of everyone associated with it," said Ajey Lele, a consultant at New Delhi's Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses.

"When the world looks at a mission like this, they aren't looking at ISRO in isolation."

RUSSIA'S CRUNCH

Despite Western sanctions over its war in Ukraine and increasing isolation, Russia managed to launch a moonshot. But some experts doubt its ability to fund a successor to Luna-25. Russia has not disclosed what it spent on the mission.

"Expenses for space exploration are systematically reduced from year to year," said Vadim Lukashevich, an independent space expert and author based in Moscow.

Russia's budget prioritisation of the war in Ukraine makes a repeat of Luna-25 "extremely unlikely", he added.

Russia had been considering a role in NASA’s Artemis programme until 2021, when it said it would partner instead on China's moon programme. Few details of that effort have been disclosed.

China made the first ever soft landing on the far side of the moon in 2019 and has more missions planned. Space research firm Euroconsult estimates China spent $12 billion on its space programme in 2022.

NASA'S PLAYBOOK

But by opening to private money, NASA has provided the playbook India is following, officials there have said.

Elon Musk’s SpaceX, for example, is developing the Starship rocket for its satellite launch business as well as to ferry NASA astronauts to the moon’s surface under a $3-billion contract.

Beyond that contract, SpaceX will spend roughly $2 billion on Starship this year, Musk has said.

U.S. space firms Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines are building lunar landers that are expected to launch to the moon's south pole by year's end, or in 2024.

And companies such as Axiom Space and Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin are developing privately funded successors to the International Space Station. On Monday, Axiom said it raised $350 million from Saudi and South Korean investors.

Space remains risky. India’s last attempt to land failed in 2019, the same year an Israeli startup failed at what would have been the first privately funded moon landing. Japanese startup ispace had a failed landing attempt this year.

"Landing on the moon is hard, as we’re seeing,” said Bethany Ehlmann, a professor at California Institute of Technology, who is working with NASA on a 2024 mission to map the lunar south pole and its water ice.

"For the past few years, the moon seems to be eating spacecraft."

(This story has been refiled to add Reuters Instrument Code in paragraph 21)

(Editing by Kevin Krolicki and Clarence Fernandez)

Russia's moon crash ‘raises the stakes’ for India's successful landing

Matt Berg

Mon, August 21, 2023

Aijaz Rahi/AP Photo

India’s lunar lander is working “perfectly,” the head of India’s space agency said Monday, just days after Russia crashed its spacecraft into the moon.

The Chandrayaan-3 lander is scheduled to land on the moon on Wednesday with no contingencies expected, Indian Space Research Organization Chair S. Somanath said in a statement.

Now, experts say New Delhi has a huge opportunity to cement its space prowess.

“It raises the stakes of success. India has always been viewed by the world as a junior spacefaring state,” said Peter Garretson, a senior fellow in defense studies at the American Foreign Policy Council and a former Defense Department official. “If India can succeed where Russia has failed, it signals a new pecking order in space.”

After a surprise launch by Russia’s space agency in early August to beat India’s Chandrayaan-3 lander to the lunar south pole — Moscow’s first lunar mission in nearly half a century — the spacecraft plunged into the moon’s surface after its pre-landing maneuvers malfunctioned.

Both countries aimed for the region because of its potential supply of water, which could provide the building blocks for breathable oxygen, drinking water and even rocket fuel for spacefaring nations with bases on the south pole.

There’s no guarantee of such resources on the surface. But back on Earth, New Delhi could reap different rewards.

“It will signal an arrival of sorts on the global stage and change the perception of India … ‘looking up’ to Russian achievements and technological know-how,” Garretson said. “If successful, the leadership order has flipped.”

Boosting India’s space program has been a priority for Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and the landing will “script a new history of planetary exploration” if successful, Indian politician Jitendra Singh said in a statement.

In July, India became the 26th country to sign on to NASA’s Artemis Accords, Washington’s preferred principles for space exploration as more countries aim for the cosmos.

Chandrayaan-3, Luna-25: The race to unravel the mysteries of Moon's south pole

Soutik Biswas - India correspondent

Mon, August 21, 2023

A passenger plane flying over the full Moon before landing in California in early August

The sun lingers slightly above or just below the horizon, while towering mountains project dark shadows.

Deep craters provide a haven for unending darkness. Some of these areas have been shielded from sunlight for billions of years. In these regions, temperatures plummet to astonishing lows of -414F (-248C) - because the Moon has no atmosphere to warm up the surface. No human has set foot in this completely unexplored world.

The Moon's south pole, according to Nasa, is full of "mystery, science and intrigue".

No wonder then that there's a so-called space race to reach the south pole of the Moon, far away from the Apollo landing sites clustered around the equator.

Russia's Luna-25 spacecraft crashes into Moon

This week, India plans to land a robotic probe - Chandrayaan-3 - near the south pole. (On Sunday, Russia's Luna-25, which was expected to be the first to do this, crashed into the Moon). India is also planning a joint Lunar Polar Exploration (Lupex) mission with Japan to explore the shadowed regions or the 'dark side of the Moon' by 2026.

Why is the south pole emerging as a compelling scientific destination? Scientists say a key reason is water.

An image sent by Chandrayaan-3 show the craters on the lunar surface

Data gathered by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, a Nasa spacecraft that has been orbiting the Moon for 14 years, suggests water ice is present in some of the large permanently shadowed craters that could potentially sustain humanity. (Water exists as a solid or vapour on the Moon because of the vacuum - the Moon doesn't have enough gravity to hold an atmosphere.) India's Chandrayaan-1 lunar mission was the first to find evidence of water on the Moon in 2008.

"It is yet to be proven that the water ice is accessible or mineable. In other words, are there reserves of water that can be extracted economically?" Clive Neal, a professor of planetary geology at the US University of Notre Dame, told me.

The prospect of finding water on the Moon is exciting in many ways, scientists say.

India's latest Moon mission sends first photos

The frozen water untainted by the Sun's radiation might have accumulated in cold polar regions over millions of years, leading to the accumulation of ice on or near the surface. This provides a unique sample for scientists to analyse and understand the history of water in our solar system.

"We can address questions such as where did the water come from and when, and what are the implications for the evolution on life on Earth," says Simeon Barber, a planetary scientist at UK's The Open University, who also works with the European Space Agency.

There are other "pragmatic" reasons for accessing water on or just below the Moon's surface, says Prof Barber.

Many countries are planning new human missions to the Moon, and the astronauts will need water for drinking and sanitation.

Transporting equipment from Earth to the Moon involves overcoming the Earth's gravitational pull. The larger the equipment, the more rocket and fuel load would be needed to achieve a successful landing on the Moon. The new commercial space companies charge around $1m to take a kilogram of payload to the Moon.

"That's $1m per litre of drinking water! Space entrepreneurs no doubt see lunar ice as an opportunity to supply astronauts with locally sourced water," says Prof Barber.

The private firms helping India aim high in space

That's not all. Water molecules can be broken apart into hydrogen and oxygen atoms, and both can be used as propellants to fire rockets. But first scientists need to know how much ice is there on the Moon, in what forms, and whether it can be extracted efficiently and purified to make it safe to drink.

Also, some extremes at the south pole are bathed in sunlight for extended periods of time, up to 200 Earth days of constant illumination. "Solar power is another resource [to set up a lunar base and power equipment] potential that the pole has," says Noah Petro, a project scientist at Nasa.

The lunar south pole also sits on the rim of a massive impact crater of the solar system. Spanning a diameter of 2,500km (1,600 miles) and reaching depths of up to 8km, this crater is one of the most ancient features within the solar system. "By landing on the pole you can begin to understand what is going on with this large crater," says Mr Petro.

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, a Nasa spacecraft, has been orbiting the Moon for 14 years

Navigating the lunar pole with rovers, space suits and sampling tools in a distinctly different light and thermal environment in contrast to previously explored equatorial sites also promises to yield valuable insights.

But scientists are chary of calling this a race to the south pole. "These missions have been planned for decades and got delayed so many times. Race is not critical to our understanding of the Moon. The last time there was a real space race, we ended up losing interest in the Moon after three years and haven't returned to its surface in 50 years," says Vishnu Reddy, a professor of planetary sciences at the University of Arizona.

The Indian and Russian missions also had some common objectives, scientists point out.

Amazon's Jeff Bezos to help Nasa return to Moon

Both aimed to land with similarly sized spacecraft in the south polar region, further south of the equator than any previous lunar mission.

Following an unsuccessful landing attempt in 2019, India will seek to showcase its capability for precise lunar touchdown near the pole. It also aims at examining the Moon's exosphere - an extremely sparse atmosphere - and analysing the polar regolith, an accumulation of loose particles and dust amassed over billions of years that rest above a bedrock.

Luna-25's objectives included the analysis of the polar regolith's composition, as well as an examination of plasma and dust elements of the lunar pole exosphere.

To be sure, the landing site of the Indian orbiter is a "bit away from the actual pole". "But the data [it provides] will be fascinating," says Prof Neal.

Russia and China have plans to build a lunar space station to develop research facilities on the surface of the Moon, in orbit or both. Russian is planning more Luna missions. Nasa is sending instruments on commercial landers to go to places across the Moon. Japan is preparing to send a smart lander (the SLIM mission) on 26 August - a small-scale mission to demonstrate accurate lunar landing techniques by a small explorer.

And, of course, Nasa's Artemis programme aims to put astronauts back on the Moon in a series of spaceflights, more than half a century after the last Apollo mission.

"The Moon is like a giant puzzle. We have some of the pieces, the corners and edges based on samples and lunar meteorite data. We have a picture of what the Moon is like, but it is incomplete," says Mr Petro.

"The Moon is still surprising us."

Geeta Pandey - BBC News, Delhi

Mon, August 21, 2023

One of the latest images sent by the Vikram lander

India's space agency has released images of the far side of the Moon as its third lunar mission attempts to locate a safe landing spot on the little-explored south pole.

The pictures have been taken by Vikram, Chandrayaan-3's lander, which began the last phase of its mission on Thursday.

Vikram, which carries a rover in its belly, is due to land on 23 August.

The photos come a day after Russia's Luna-25 spacecraft crashed into the Moon after spinning out of control.

The craft - Russia's first Moon mission in nearly 50 years - was due to be the first ever to land on the south pole, but failed after encountering problems as it moved into its pre-landing orbit.

On Monday morning, the Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro) said the lander from Chandrayaan-3, which is due to touch down on Wednesday at 18:04 India time (12:34 GMT), has been mapping the landing area and taking images with its "hazard detection and avoidance" camera.

Isro added that the black-and-white images sent by this camera will assist them "in locating a safe landing area - without boulders or deep trenches".

The lunar far side is the side that faces away from the Earth and is sometimes also called "the dark side of the Moon" because so little is known about it. Scientists say landing there can be a tricky affair.

But there's a lot of interest in this part of the Moon which scientists think could hold frozen water and precious elements.

India's latest Moon mission sends first photos

Historic India Moon mission lifts off successfully

Isro said on Sunday that the lander module had been successfully lowered into an orbit closer to the Moon (of 25km by 134km) and is now waiting for the lunar Sun-rise to land.

If Chandrayaan-3 is successful, India will be first to land on the lunar south pole. It will also be only the fourth country to achieve a soft landing on the Moon after the US, the former Soviet Union and China.

Graphic showing the LVM3 launch rocket, with three engine phases, and where the Chandrayaan-3 will be while it it carried into orbit

The third in India's programme of lunar exploration, Chandrayaan-3 is expected to build on the success of its earlier Moon missions.

It comes 15 years after the country's first Moon mission in 2008, which discovered the presence of water molecules on the parched lunar surface and established that the Moon has an atmosphere during daytime.

Chandrayaan-2 - which also comprised an orbiter, a lander and a rover - was launched in July 2019 but it was only partially successful. Its orbiter continues to circle and study the Moon even today, but the lander-rover failed to make a soft landing and crashed during touchdown.

The women scientists who took India into space

Was India's Moon mission actually a success?

Isro chief Sreedhara Panicker Somanath has said that the space agency had carefully studied the data from its crash and carried out simulation exercises to fix the glitches in Chandrayaan-3, which weighs 3,900kg and cost 6.1bn rupees ($75m; £58m). The lander module weighs about 1,500kg, including the 26kg-rover Pragyaan.

The south pole of the Moon is still largely unexplored - the surface area that remains in shadow there is huge, and scientists say it means there is a possibility of water in areas that are permanently shadowed.

One of the major goals of Chandrayaan-3 is to hunt for water ice, which scientists say could support human habitation on the Moon in future. It could also be used for supplying propellant for spacecraft headed to Mars and other distant destinations.

Graphic showing how the Chandrayaan-3 will get to the Moon, from take off, to orbiting the Earth in phases until it reaches the Moon's orbit, when the lander will separate from the propulsion module before landing near the Moon's south pole

Victor Tangermann

Mon, August 21, 2023

Polar Vortex

Just days after Russia crashed its Luna-25 lunar lander on its way to the Moon's surface, India's space agency is gearing up for its own attempt.

The two countries were in a race to become the first country to softly land a craft near the lunar south pole, a region scientists believe could be rich with water ice, a key resource for potential settlement efforts.

But with Russia out of the race for now, all eyes are on India's Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft, a followup to a precursor that crash-landed on its way to the lunar surface back in 2019.

We'll be watching closely because the stakes are high. If successful, the mission could make India only the fourth country to successfully land on the Moon, following the US, the Soviet Union, and China — and, in a sense both symbolic and technical, show that it's pulling ahead of Russia's increasingly disastrous space program.

Trying Again

The lander-rover pair will attempt their treacherous journey to the south pole on Wednesday, if all goes according to plan. Officials from India's space agency ISRO told reporters on Monday that all the spacecraft's systems are working "perfectly," Reuters reports.

The mission's objectives are first to prove the country's capability of safely landing on the Moon, and then study the composition of the lunar south pole if successful.

Chandrayaan-3 features several technological upgrades over its precursor that could give it a better shot of sticking the landing later this week. For one, ISRO is giving itself a larger potential landing zone in the case of adverse conditions. It also has sturdier legs, an important because the south pole's terrain is comparatively rough.

Moon Stakes

If all goes according to plan — needless to say, that's still an astronomical "if" — the lander will release a 57-pound, six-wheeled rover that will explore the surrounding areas for evidence of water ice using an X-ray spectrometer and a laser spectroscope.

A success could catapult India ahead in the international race to establish a permanent presence on the Moon — especially now that Russia's attempt has failed.

"If Chandrayaan-3 succeeds, it will boost India's space agency's reputation worldwide," former ISRO scientist Manish Purohit told Reuters. "It will show that India is becoming a key player in space exploration."

Reuters

Tue, August 22, 2023

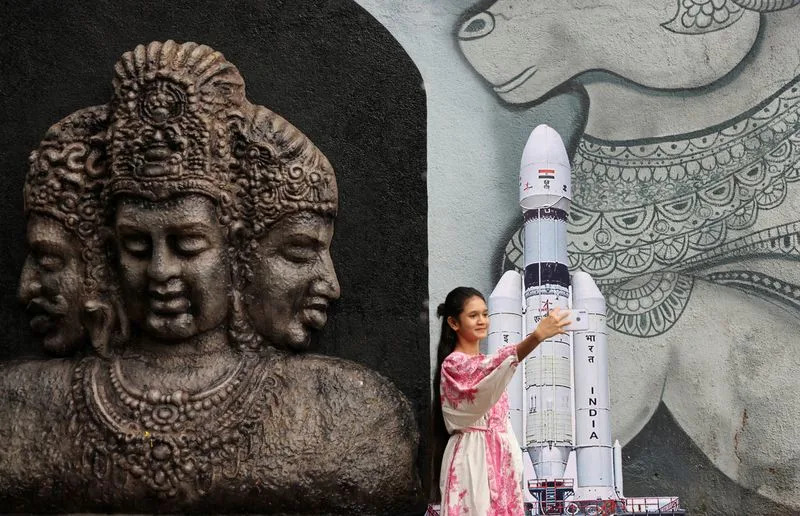

Prayer for successful launch of lunar exploration mission by ISRO in Mumbai

NEW DELHI (Reuters) - Excitement rose in India on Tuesday on the eve of a much-anticipated moon landing, with prayers held for its success, schools marshalling students to watch a live telecast of the event and space enthusiasts organising parties to celebrate.

The Indian Space Research Organisation's (ISRO) Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft is scheduled to land on the lunar south pole at 1234 GMT on Wednesday, days after the failure of a Russian vehicle trying to achieve the same feat.

Success for Chandrayaan-3 will make it the first to land on the lunar south pole, a region whose shadowed craters are thought to contain water ice that could support a future moon settlement.

India's second attempt to land on the moon after a failure in 2019 is being seen as a display of the tenacity of its scientific institutions.

Authorities and educators also hope it will encourage scientific inquiry among millions of students in the world's most populous country.

Students have sent scores of messages wishing ISRO luck for a successful landing, the agency said.

In the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, the provincial government ordered all schools to hold special screenings as "landing of India's Chandrayaan-3 is a memorable opportunity, which will not only encourage curiosity, but will also instil passion in our youth towards inquiry".

In Gujarat, the home state of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the science and technology council has invited over 2,000 school students "to witness the historic moment" on a large screen, its head Narottam Sahoo said.

The council has also organised talks by ISRO scientists. The event will be shown live across Gujarat's 33 district community science centres.

The state culture ministry in the eastern city of Kolkata is throwing a "Science Party" to celebrate the mission, asking people to "embark on exhilarating educational adventure" with a live telecast.

Hindu religious prayer ceremonies were organised on Tuesday in Mumbai and Varanasi cities for the success of the mission.

Srikant Chunduri, an entrepreneur and founder of a group of space enthusiasts called "Agnirva", said he has arranged a "watch party" for the landing at a popular Bengaluru restaurant.

"If we want to build a community for space enthusiasts, (there is) nothing more momentous than this landing to get people together," he told Reuters.

ISRO has been sharing regular updates of the mission through posts on X, formerly Twitter.

"The mission is on schedule. Systems are undergoing regular checks. Smooth sailing is continuing," it said on Tuesday.

"The Mission Operations Complex (MOX) is buzzed with energy & excitement!"

(Reporting by Nivedita Bhattacharjee in Bengaluru, Saurabh Sharma in Lucknow, Subrata Nag Choudhury in Kolkata, Sumit Khanna in Ahmedabad, Sunil Kataria in New Delhi; Writing by Krishn Kaushik; Editing by YP Rajesh and Raju Gopalakrishnan)