Local Journalism Initiative

Mon, October 2, 2023

A group of wild Atlantic salmon conservationists that's been working for years to eradicate smallmouth bass from the Miramichi River watershed says it's abandoning the project, due to a lack of government action and problems posed by protesters and cottage owners they consider uninformed.

Instead, the Working Group on Smallmouth Bass Eradication in the Miramichi is calling upon the federal and provincial governments to uphold their responsibilities and get the job done.

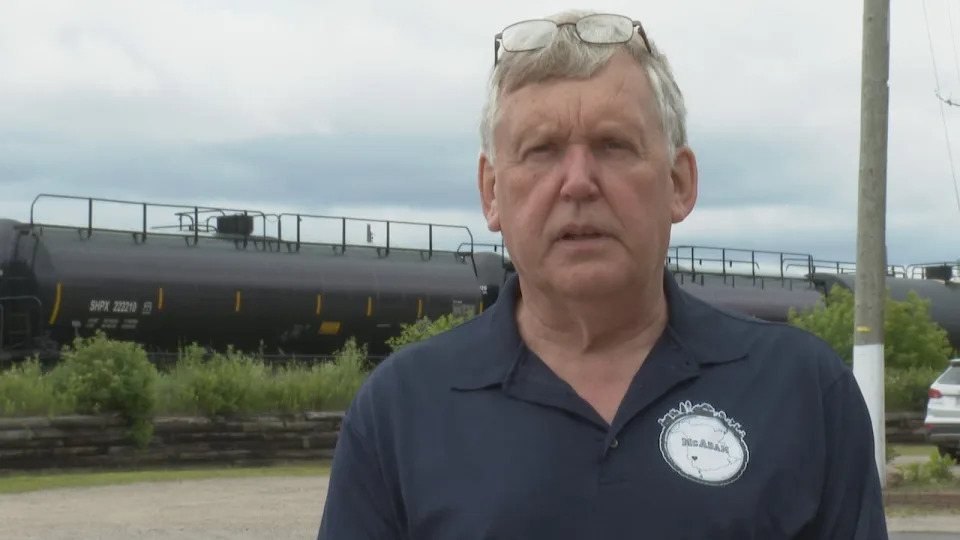

“Smallmouth bass will now colonize the watershed,” working group spokesperson Neville Crabbe said in a news release Friday morning.

“They will eat trout, salmon, and other native species, and fight for habitat. The irreversible negative consequences of this invasion are the result of one of the most consequential environmental crimes in New Brunswick history; the illegal introduction of invasive smallmouth bass to Miramichi Lake.”

After years of false starts and disruptions, last September the group – which includes the Miramichi Salmon Association and the North Shore Mi’kmaq District Council, representing seven eastern Indigenous communities – completed one part of the eradication project – the application of the natural chemical rotenone to Lake Brook and a 15-kilometre stretch of the Southwest Miramichi River.

That operation, the group said, went according to plan, wiping out a few dozen smallmouth bass and hundreds of juvenile salmon – parr – along with an estimated 50 to 75 adult salmon.

The group said the move was necessary to help preserve the annual run of up to 25,000 returning salmon from the ocean. The large fighting fish is considered iconic in New Brunswick and sacred to Indigenous communities, whereas smallmouth bass was introduced, a fish native to the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River that’s aggressive on the line but easy to catch.

Part 2 of the eradication program, now halted, would have applied the chemical to Miramichi Lake, part of the river's headwaters, which is about 170 kilometres southwest of its estuary at Miramichi.

But some cottage owners on the lake and Indigenous people from Wolastoqey communities in western New Brunswick have pushed back, arguing the heavy-handed method would do more harm than good.

Smallmouth were discovered in Miramichi Lake in 2008. Members of the working group called for decisive action from the federal government at the time, to no avail.

“We recommended using rotenone, a natural plant toxin that is safe, effective, and the most common method worldwide to deal with invasive fish,” said the working group’s release. “Instead, Fisheries and Oceans Canada chose to try and eradicate smallmouth by catching them. This approach failed, as predicted, and contributed to the spread of smallmouth outside Miramichi Lake.”

A federal official said Friday her department appreciated the hard work that the working group put into the smallmouth bass eradication project.

Isabelle Comeau, a spokeswoman for DFO, acknowledged that the invasive species poses a serious threat to fish, fish habitat, and species at risk.

But she also said her department had been working since 2009 – and continues to do so – to physically contain, control, and monitor smallmouth bass in both Miramichi Lake and the Southwest Miramichi River.

“This included maintaining a physical barrier at the lake outlet, and intensive removal activities in the lake, in the brook leading to the Miramichi River, and a 12-kilometre section of the [Southwest] Miramichi River,” she wrote in an email. “In addition, monitoring activities were conducted over time to characterize the spread of smallmouth bass in the watershed.”

Rotenone has been used before to eradicate invasive chain pickerel from Despres Lake, also part of the Southwest Miramichi watershed.

In October 2001, a rotenone treatment took place, with the provincial government leading the operation and DFO authorizing it. That eradication program was considered a success, but since then, regulations have changed.

On Friday, New Brunswick’s Department of Natural Resources and Energy Development pointed the finger at DFO, arguing it was responsible for removing invasive species from the watershed.

“The province has acted appropriately with an openness to collaborate and partner when asked,” wrote spokesperson Jason Hoyt in an email. “This was recently demonstrated as the Department of Natural Resources and Energy Development was integral to the recent Miramichi treatment operations and supported the proponent with staff and equipment for the duration of the project.

“It is too soon to comment on what next steps will be. DFO is integral to any discussion on smallmouth bass eradication in Miramichi Lake.”

DFO, however, insisted it couldn’t do the job alone. Comeau said while her department was the administrator of the aquatic invasive species regulations, management was a shared responsibility between federal and provincial governments.

“To ensure and maintain independent regulatory oversight, DFO cannot be the proponent of an eradication project in New Brunswick,” she wrote.

The working group remains frustrated that its efforts did not lead to the eradication of smallmouth bass, despite years of effort. It said it went beyond the call of duty, becoming the first non-government collective to lead an invasive fish eradication in North America and the first applicant to DFO’s new aquatic invasive species program.

"We engaged experts from Montana, California, and British Columbia to help devise a responsible plan. We participated in the Crown-led Indigenous consultation process, completed a provincial environmental assessment, and received a Fisheries Act authorization from DFO," the release states.

"In the end, we held 18 permits and licenses from 10 government agencies, an exhaustive process that took several years."

John Chilibeck, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, The Daily Gleaner