First-of-its-kind research reveals rapid changes to the Arctic seafloor as submerged permafrost thaws

A new study from MBARI researchers and their collaborators is the first to document how the thawing of permafrost, submerged underwater at the edge of the Arctic Ocean, is affecting the seafloor. The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on March 14, 2022.

Numerous peer-reviewed studies show that thawing permafrost creates unstable land which negatively impacts important Arctic infrastructure, such as roads, train tracks, buildings, and airports. This infrastructure is expensive to repair, and the impacts and costs are expected to continue increasing.

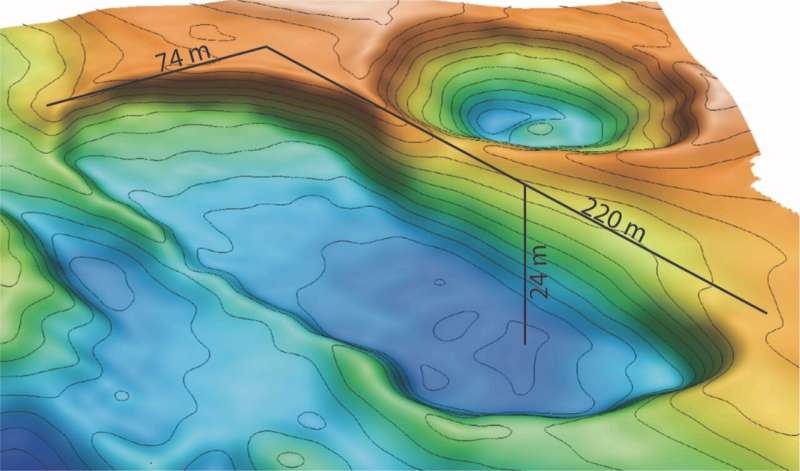

Using advanced underwater mapping technology, MBARI researchers and their collaborators revealed that dramatic changes are happening to the seafloor as a result of thawing permafrost. In some areas, deep sinkholes have formed, some larger than a city block of six-story buildings. In other areas, ice-filled hills called pingos have risen from the seafloor.

"We know that big changes are happening across the Arctic landscape, but this is the first time we've been able to deploy technology to see that changes are happening offshore too," said Charlie Paull, a geologist at MBARI and one of the lead authors of the study. "This groundbreaking research has revealed how the thawing of submarine permafrost can be detected, and then monitored once baselines are established."

While the degradation of terrestrial Arctic permafrost is attributed in part to increases in mean annual temperature from human-driven climate change, the changes the research team has documented on the seafloor associated with submarine permafrost derive from much older, slower climatic shifts related to our emergence from the last ice age. Similar changes appear to have been happening along the seaward edge of the former permafrost for thousands of years.

"There isn't a lot of long-term data for the seafloor temperature in this region, but the data we do have aren't showing a warming trend. The changes to seafloor terrain are instead being driven by heat carried in slowly moving groundwater systems," explained Paull.

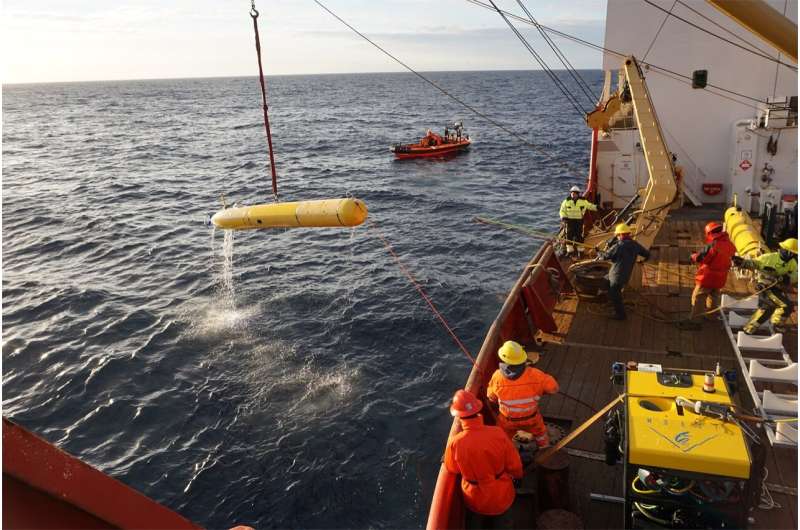

"This research was made possible through international collaboration over the past decade that has provided access to modern marine research platforms such as MBARI's autonomous robotic technology and icebreakers operated by the Canadian Coast Guard and the Korean Polar Research Institute," said Scott Dallimore, a research scientist with the Geological Survey of Canada, Natural Resources Canada, who led the study with Paull. "The Government of Canada and the Inuvialuit people who live on the coast of the Beaufort Sea highly value this research as the complex processes described have implications for the assessment of geohazards, creation of unique marine habitat, and our understanding of biogeochemical processes."

Background

The Canadian Beaufort Sea, a remote area of the Arctic, has only recently become accessible to scientists as climate change drives the retreat of sea ice.

Since 2003, MBARI has been part of an international collaboration to study the seafloor of the Canadian Beaufort Sea with the Geological Survey of Canada, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and since 2013, with the Korean Polar Research Institute.

MBARI used autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) and ship-based sonar to map the bathymetry of the seafloor down to a resolution of a one-meter square grid, or roughly the size of a dinner table.

Paull and the team of researchers will return to the Arctic this summer aboard the R/V Araon, a Korean icebreaker. This trip with MBARI's long-time Canadian and Korean collaborators—along with the addition of the United States Naval Research Laboratory—will help refine our understanding of the decay of submarine permafrost.

Two of MBARI's AUVs will map the seafloor in remarkable detail and MBARI's MiniROV—a portable remotely operated vehicle—will enable further exploration and sampling to complement the mapping surveys.Researchers discover mysterious holes in the seafloor off Central California

More information: Rapid seafloor changes associated with the degradation of Arctic submarine permafrost, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2119105119

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Provided by Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

Melting Permafrost Is Creating Giant Craters And Hills On The Arctic Seafloor

By Stephen Luntz

Submarine surveys of the seafloor beneath the Arctic Ocean have revealed deep craters appearing off the Canadian coastline. The scientists involved attribute these to gasses released as permafrost melts. The causes, so far, lie long before humans started messing with the planet’s thermostat, but that could be about to change.

For millions of years, soil has been frozen solid over large areas of the planet, both on land and under the ocean, even where snow melts at the surface to leave no permanent ice sheet. Known as permafrost, this frozen layer traps billions of tonnes of carbon dioxide and methane. It is thought the sudden melting of similar areas around 55 million years ago set off the Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, when temperatures rose sharply over the space of a few thousand years.

Now the permafrost is melting again, revealed in plumes of bubbles coming to the surface in shallow oceans, the collapsing of Arctic roads, ruined scientific equipment, and great craters that suddenly appeared in Siberia. For the first time, scientists have revealed in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences what all this is doing to part of the Arctic Ocean’s seafloor.

Dr Charles Paull of Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute and co-authors ran four surveys of the storied Beaufort Sea between 2010 and 2019 using autonomous underwater vehicles assisted by icebreakers at the surface. They restricted their observations to depths between 120 and 150 meters (400-500 feet) as in most places this captures the permafrost's outer margin.

The paper reports numerous steep-sided depressions up to 28 meters (92 feet), along with ice-filled hills up to 100 meters (330 feet) wide known as pingos. Some of these, including a deep depression 225 meters (738 feet) long and 95 meters (312 feet) across, appeared between successive surveys, rather than being long-standing features. Others expanded in the time the team were watching.

The depressions are the result of groundwater ascending up the continental slope. Sometimes the groundwater freezes from contact with colder material, causing the ground surface to heave upwards and produce pingos.

The research was possible because the Beaufort Sea, once too icebound for research like this, is melting fast. That trend is, the authors agree, a consequence of human emissions of Greenhouse gases. The same goes for the widespread disappearance of permafrost on land.

However, the extra heat those gasses put into the global system has yet to penetrate to the depths Paull and co-authors were studying. Here, temperatures operate on a much slower cycle, buffered by so much water, and are still responding to the warming that took place as the last glacial era ended. At the current rate, it would take more than a thousand years to produce the topography the team observed.

“There isn’t a lot of long-term data for the seafloor temperature in this region, but the data we do have aren’t showing a warming trend,” Paull said. “The changes to seafloor terrain are instead being driven by heat carried in slowly moving groundwater systems.”

The natural melting of Ice Age permafrost releases gasses that warm the planet, part of a reinforcing interglacial era cycle, but the effect is slow enough to present little problem for humans or other species. As human-induced atmospheric heat permeates the oceans at these levels things could accelerate dramatically, and the authors see their work as establishing a baseline so we know if that occurs.

Giant, 90ft Deep Craters Are Appearing on the Arctic Seafloor

Enormous craters measuring 90 feet in depth have appeared on the seafloor of the Arctic Ocean.

The craters, scientists say, are forming as a result of thawing submerged permafrost on the edge of the Beaufort Sea in northern Canada, with retreating glaciers from the last ice age driving the change and not recent climate warming.

Permafrost is ground that is permanently frozen—in some cases for hundreds of thousands of years. In the Arctic, which is warming faster than any other region of Earth, permafrost is thawing, causing the ground to become unstable.

As the soil thaws, organic matter trapped within starts to break down, causing the release of methane and other greenhouse gasses. As these gasses are released, pressure builds.

On land, the impact is clear. In Siberia, there is footage showing the land wobbling "like jelly" beneath people's feet.

Eventually, when the pressure reaches a tipping point, the land explodes, leaving massive craters behind. One person who witnessed this happening described it as being "as if the earth was breathing."

In 2019, scientists in Siberia discovered a patch of ocean where the sea was "boiling" with methane, with concentrations of the gas around seven times higher than the global average.

Two years earlier, a different team of researchers found evidence of huge craters—some over 3,000 feet wide—on the floor of the Barents Sea, north of Norway and Russia. They said these craters had formed as a result of methane explosions that took place thousands of years earlier

To better understand what impact thawing permafrost is having beneath the ocean, researchers led by Charles K. Paull, a senior scientist at California's Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, used advanced mapping technology to observe changes to the seafloor over the course of a decade.

They conducted surveys in the Beaufort Sea between 2010 and 2019 to map topographical changes resulting from thawing permafrost.

Findings showed that at depths between around 400 and 500 feet, huge depressions with steep sides were forming. The largest was 90 feet deep. Their findings are published in scientific journal PNAS.

Paull told Newsweek they were shocked at their findings, with the craters far larger than they had anticipated.

He said the team does not believe the craters formed in explosive events: "The evidence suggests that the submarine features we observed forming are essentially sink-holes and retreating scarps, collapsing into void space left behind by the thawing of ice-rich permafrost."

Unlike terrestrial permafrost, climate change is not driving the seafloor to thaw. Instead, the shift is the result of older climatic shifts relating to the end of the last ice age, around 11,700 years ago. Heat is being carried to the permafrost via slow-moving groundwater systems.

The team plans to return to the Arctic this summer to look more closely at the decaying seafloor permafrost.

Julian Murton, Professor of Permafrost Science at the U.K.'s University of Sussex, who was not involved in the study, told Newsweek he was surprised at how quickly the seafloor topography had changed.

"Some changes are as rapid or even more rapid than the better-known landsurface topographic changes driven by thaw of ice-rich permafrost in the Arctic," he said. "I had assumed that thermal inertia associated with thick relict permafrost and with overlying seawater led to slow changes in seafloor topography.

"Clearly this assumption is shown to be wrong, at least locally, by this fascinating, high-resolution study."

Paull said the longer term consequences of seafloor permafrost thaw is unclear: "Since some methane is trapped in permafrost, thawing permafrost inevitably releases methane, an important greenhouse gas," he said.

"However, we don't have data to understand whether the rate of methane release from decaying submarine permafrost has changed in recent times in this area.

"The changes we've documented derive from much older, slower climatic shifts related to Earth's emergence from the last ice age, and appear to have been happening along the edge of the permafrost for thousands of years. Whether anthropogenic climate change will accelerate the process remains unknown."

As Siberia's Coldest Regions Burn, the 'Gateway to the Underworld' Grows

Enormous, 165 Ft Deep Crater Opens on Siberia's Arctic Tundra

Sea 'Boiling' with Methane in Siberia is Unlike Anything Seen Before

No comments:

Post a Comment