FIRST READING: Canadian economic productivity is in freefall

Opinion by Tristin Hopper •

Construction workers assemble a crane high in the air in Toronto in this 2021 photo.© Provided by National Post

First Reading is a daily newsletter keeping you posted on the travails of Canadian politicos, all curated by the National Post’s own Tristin Hopper.

Although Canadian economic growth is just barely keeping its head above water, data keep emerging to show that, for the average Canadian, the economic situation is getting progressively worse.

New data from Statistics Canada show that Canadian labour productivity has dropped for the fourth consecutive quarter. Compared to this time last year, the average Canadian is now producing two per cent less during every hour they spend at work.

And it’s not like our per-capita productivity was all that good to begin with. An analysis by University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe found that Canada’s per-person rate of economic output is now on the level of some of the poorest states in the U.S.

Ontario’s rate of per-capita productivity, for instance, is now about the same as Alabama. And even Alberta – Canada’s most unambiguously wealthy province – wouldn’t come close to cracking the top 10 among richest per-capita U.S. states.

Tombe noted that recent drops in productivity have effectively erased five years of gains, sending Canada right back to the productivity levels of 2017. If Canada had instead spent those last five years matching the productivity growth of the United States, Tombe estimates that it would have meant an extra $5,500 in increased economic output per Canadian.

“Given how closely wages are tied to productivity, this directly affects our living standards and, in my view, poses a bigger affordability challenge than recent high inflation,” he wrote.

The new figures on dropping productivity add to revelations in May that Canada was already well into a “per-capita” recession.

Official figures show that Canada has not met the technical definition of a recession: two consecutive quarters of negative growth. As of the last count, GDP growth stood at 0.3 per cent in the last quarter of 2022, just enough for policymakers to be able to say that the economy isn’t contracting.

But those statistics change when accounting for the fact that Canada is packing in unprecedented numbers of new immigrants, meaning that a relatively stagnant national economy is now being shared among a pool of people that is getting three per cent larger every year.

Over the weekend, the Canadian population officially passed 40 million people thanks largely to a dramatic scale-up in the country’s annual intake of permanent residents. In 2022 alone, Canada added one million newcomers, the equivalent of the entire population of Nova Scotia.

The housing-news publication Better Dwelling recently crunched the numbers on Canada’s economic performance as measured at a per-capita level. What it found was that, while the aggregate economy may be keeping its head above water, the average Canadian would have experienced the last quarter of 2022 as a 0.9 per cent contraction.

“Canadians are likely seeing an erosion in quality of life, and while incomes are rising they aren’t rising enough to compete with inflation,” wrote Better Dwelling.

And overarching everything are OECD projections showing that Canada is on track to become the world’s worst-performing advanced economy.

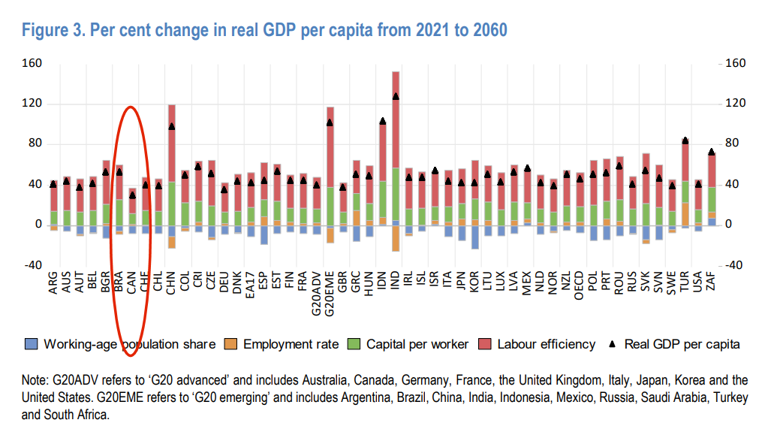

In Dec. 2021, a report by the OECD predicted how GDP growth was expected to look in each of the world’s developed economic between now and 2060. In terms of “real per capita GDP growth,” Canada was ranked dead last.

OECD projection on real per capita GDP growth into 2060. Canada, which has the lowest of any developed nation, is circled in red.© OECD

For decades on end, the Canadian economy was expected to yield annual growth rates of no more than 0.8 per cent. So while Canada wouldn’t necessarily decline, its economy would remain stagnant, causing living standards to drop as compared to its peer nations.

At the time, an analysis by the Business Council of British Columbia blamed a political class that had “lost interest in efforts to raise workers’ productivity.”

“Past generations of young Canadians entering the workforce could look forward to favourable tailwinds lifting real incomes over their working lives. That’s no longer the case,” the council concluded.

No comments:

Post a Comment