Black public figures from Simone Biles to Naomi Osaka are helping us put one simple word at the top of our vocabulary: no

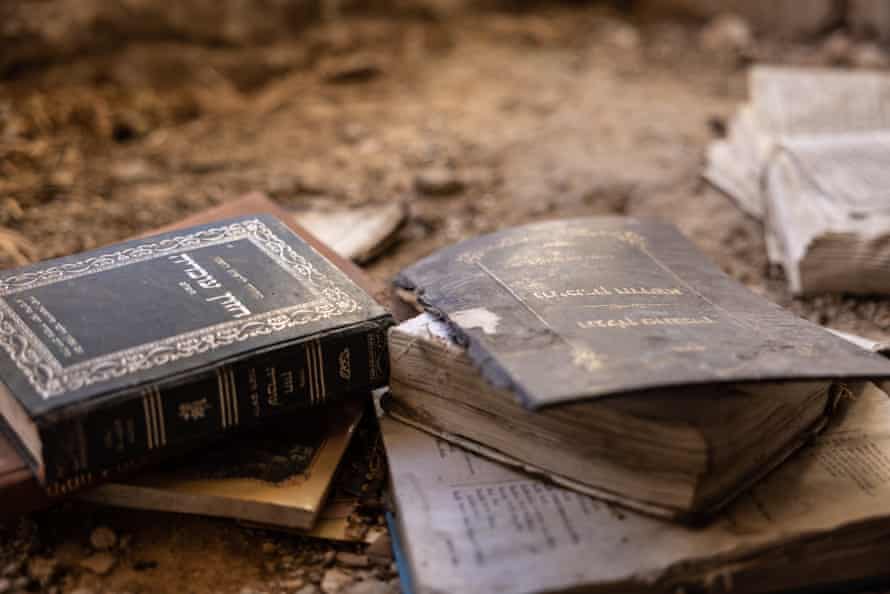

‘Some might wrongly view this refusal as a symptom of millennial dysfunction and entitlement.’ Photograph: Jamie Squire/Getty Images

Casey Gerald

Wed 28 Jul 2021 19.08 BST

I can hardly do a proper cartwheel, so I’m hesitant to opine on Simone Biles’s decision to withdraw from the Tokyo Olympics this week, telling the press and the world: “I have to focus on my mental health.” I can’t stay silent, though, because I know she’s not alone.

As a former college football player, I can imagine the psychological price Olympians pay to squeeze every ounce of greatness into a tiny window of life. As a Black man raised by a cadre of women, I can imagine the tax Black women pay because of our national commitment to “trust” them, which really just means “let them do all the work.” Or, in the case of Simone Biles, “let her put the whole country on her back”.

Faced with these burdens, however, Biles did not simply quit. She refused. With her bold act she stepped into a beautiful, radical, often overlooked tradition, what I call the Black Art of Escape. That tradition is how I believe we, Black people, have managed to live in a country that’s made to destroy us. We’ve been told a great deal about our people’s strategies of resistance and protest. The great Olympic example of this, of course, is Tommie Smith and John Carlos’s black-gloved Black Power salute on the medal stand at the 1968 Games in Mexico City. We’ve been told about our people’s strategies of respectability and exceptionalism, perhaps embodied best by the icon Jesse Owens, who became the first American to win four track and field gold medals at a single Olympics, a feat he accomplished while Adolf Hitler looked on.

Biles’s decision harkens to a third way Black people have survived this country: flight.

Throughout the diaspora, tales of flying Africans were shared to give hope to the enslaved, hope that no matter how their slavers treated them, no matter how their country treated them, they had a freedom on the inside that the world had not given, and the world could not take away. This folkloric tradition inspired Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, in which Guitar tells Milkman: “Wanna fly, you got to give up the shit that weighs you down.”

For years we have watched Simone Biles soar through the air, across the mat, on balance beams and vaults. She’s twisted her body in ways that defy gravity, defy human comprehension. Her genius has made her the most decorated American gymnast in history, even as she’s competed with broken bones, not to mention the unconscionable abuse she endured at the hands of the former USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar.

Yet, despite her many other accomplishments, I believe Biles’s decision to forgo her chance at another medal in Tokyo will stand as her greatest achievement of all. That Biles, perhaps the greatest gymnast ever, on the biggest stage of all, chose herself over yet another accomplishment, gives hope to a generation of Black Americans, famous and not, that we too might refuse the terms of success our country has offered us. Now, some might say she betrayed her teammates. Betrayed her country. I say: good for her. I think back to EM Forster’s great essay What I Believe, in which he writes: “I hate the idea of causes, and if I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.” If it takes guts to betray one’s country and choose one’s friend, how much more courage is required to truly choose oneself, when the whole world thinks they need you – when your team, your family, thinks they need you? But as a therapist once wisely told me: you can’t give what you don’t have.

America has always asked Black people to give everything we’ve got and then give what we don’t have. And if we did not give it, it was taken wilfully – plundered, as Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote.

Biles’s courageous decision echoes the actions of other Black public figures, from Naomi Osaka to Leon Bridges, who are refusing to sacrifice their sanity, their peace, for another gold medal or another platinum record. They are helping us all build a new muscle, helping us put one simple word at the top of our vocabulary: no.

Some might wrongly view this refusal as a symptom of millennial dysfunction and entitlement. The truth is that many of us came of age against the backdrop of 9/11 and the pyrrhic “war on terror”. We entered the workforce in the midst of the Great Recession. We cast our first votes for a Black president, only to then witness a reign of terror against Black people, young and old, at the hands of the state. (Not to mention the traumatic four years under our last president, who dispatched troops to brutalize peaceful protests for Black lives.) We are tired. We are sad. As the brilliant musician and producer Terrace Martin, perhaps best known for his work with Kendrick Lamar, told me recently: “I don’t know anybody sleeping well.”

I’m reminded of that great scene in the film Network, when the unstable newscaster convinces viewers all over the country to rush to their windows and scream out into the street: “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not gonna take this any more!” Might Biles’s act of deep and brave self-love spark the largest wave of refusal in the history of this country? I believe it’s possible.

We are, I believe, witnessing the beginning of a great refusal, when a generation of Black Americans decide to, in the words of Maxine Waters, reclaim our time. Simone Biles, famous for what she does in the air, has shown the way by standing her ground.

Casey Gerald is the author of There Will Be No Miracles Here

Wed 28 Jul 2021 19.08 BST

I can hardly do a proper cartwheel, so I’m hesitant to opine on Simone Biles’s decision to withdraw from the Tokyo Olympics this week, telling the press and the world: “I have to focus on my mental health.” I can’t stay silent, though, because I know she’s not alone.

As a former college football player, I can imagine the psychological price Olympians pay to squeeze every ounce of greatness into a tiny window of life. As a Black man raised by a cadre of women, I can imagine the tax Black women pay because of our national commitment to “trust” them, which really just means “let them do all the work.” Or, in the case of Simone Biles, “let her put the whole country on her back”.

Faced with these burdens, however, Biles did not simply quit. She refused. With her bold act she stepped into a beautiful, radical, often overlooked tradition, what I call the Black Art of Escape. That tradition is how I believe we, Black people, have managed to live in a country that’s made to destroy us. We’ve been told a great deal about our people’s strategies of resistance and protest. The great Olympic example of this, of course, is Tommie Smith and John Carlos’s black-gloved Black Power salute on the medal stand at the 1968 Games in Mexico City. We’ve been told about our people’s strategies of respectability and exceptionalism, perhaps embodied best by the icon Jesse Owens, who became the first American to win four track and field gold medals at a single Olympics, a feat he accomplished while Adolf Hitler looked on.

Biles’s decision harkens to a third way Black people have survived this country: flight.

Throughout the diaspora, tales of flying Africans were shared to give hope to the enslaved, hope that no matter how their slavers treated them, no matter how their country treated them, they had a freedom on the inside that the world had not given, and the world could not take away. This folkloric tradition inspired Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, in which Guitar tells Milkman: “Wanna fly, you got to give up the shit that weighs you down.”

For years we have watched Simone Biles soar through the air, across the mat, on balance beams and vaults. She’s twisted her body in ways that defy gravity, defy human comprehension. Her genius has made her the most decorated American gymnast in history, even as she’s competed with broken bones, not to mention the unconscionable abuse she endured at the hands of the former USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar.

Yet, despite her many other accomplishments, I believe Biles’s decision to forgo her chance at another medal in Tokyo will stand as her greatest achievement of all. That Biles, perhaps the greatest gymnast ever, on the biggest stage of all, chose herself over yet another accomplishment, gives hope to a generation of Black Americans, famous and not, that we too might refuse the terms of success our country has offered us. Now, some might say she betrayed her teammates. Betrayed her country. I say: good for her. I think back to EM Forster’s great essay What I Believe, in which he writes: “I hate the idea of causes, and if I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.” If it takes guts to betray one’s country and choose one’s friend, how much more courage is required to truly choose oneself, when the whole world thinks they need you – when your team, your family, thinks they need you? But as a therapist once wisely told me: you can’t give what you don’t have.

America has always asked Black people to give everything we’ve got and then give what we don’t have. And if we did not give it, it was taken wilfully – plundered, as Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote.

Biles’s courageous decision echoes the actions of other Black public figures, from Naomi Osaka to Leon Bridges, who are refusing to sacrifice their sanity, their peace, for another gold medal or another platinum record. They are helping us all build a new muscle, helping us put one simple word at the top of our vocabulary: no.

Some might wrongly view this refusal as a symptom of millennial dysfunction and entitlement. The truth is that many of us came of age against the backdrop of 9/11 and the pyrrhic “war on terror”. We entered the workforce in the midst of the Great Recession. We cast our first votes for a Black president, only to then witness a reign of terror against Black people, young and old, at the hands of the state. (Not to mention the traumatic four years under our last president, who dispatched troops to brutalize peaceful protests for Black lives.) We are tired. We are sad. As the brilliant musician and producer Terrace Martin, perhaps best known for his work with Kendrick Lamar, told me recently: “I don’t know anybody sleeping well.”

I’m reminded of that great scene in the film Network, when the unstable newscaster convinces viewers all over the country to rush to their windows and scream out into the street: “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not gonna take this any more!” Might Biles’s act of deep and brave self-love spark the largest wave of refusal in the history of this country? I believe it’s possible.

We are, I believe, witnessing the beginning of a great refusal, when a generation of Black Americans decide to, in the words of Maxine Waters, reclaim our time. Simone Biles, famous for what she does in the air, has shown the way by standing her ground.

Casey Gerald is the author of There Will Be No Miracles Here