Activists say Lifta, abandoned during the 1948 war, must be preserved in the face of Israeli construction plans

Israel’s land authority released plans for the tender for Lifta’s redevelopment on Jerusalem Day, and many Palestinians saw the move as political. Photograph: Stefanie Glinski/The Guardian

by Stefanie Glinski in Jerusalem

THE GUARDIAN

Wed 28 Jul 2021

The ancient Palestinian village of Lifta sits on a quiet hillside minutes from Jerusalem’s bustling modern centre. Abandoned when its residents fled during the 1948 war, it has been left unchanged – frozen in time – ever since.

Today, however, its overgrown domed stone houses with arched windows, built during the early Ottoman Empire and resting on even older ruins dating back to the Iron Age, are at risk of being demolished to make way for a luxurious resort of villas, hotels and shops.

Lifta was abandoned when its residents fled during the 1948 war. Photograph: Stefanie Glinski/The Guardian

In a joint Israeli-Palestinian initiative, activists are bracing for a legal battle to try to save the village, which stands as a reminder of the 1948 expulsions of Palestinians from West Jerusalem.

Israel’s land authority announced in May that it planned to issue a tender for Lifta’s redevelopment and bidding is expected to open on Thursday.

A court prevented a similar initiative in 2012, when it ruled that a detailed survey of the site’s history and archaeology must take place before any potential construction work could start.

Plans for the tender were released on Jerusalem Day, a holiday commemorating the establishment of Israeli control over the Old City. Many Palestinians, who believe any new development would erase the area’s history, saw the move as political, and Lifta quickly became a flashpoint.

In a joint Israeli-Palestinian initiative, activists are bracing for a legal battle to try to save the village, which stands as a reminder of the 1948 expulsions of Palestinians from West Jerusalem.

Israel’s land authority announced in May that it planned to issue a tender for Lifta’s redevelopment and bidding is expected to open on Thursday.

A court prevented a similar initiative in 2012, when it ruled that a detailed survey of the site’s history and archaeology must take place before any potential construction work could start.

Plans for the tender were released on Jerusalem Day, a holiday commemorating the establishment of Israeli control over the Old City. Many Palestinians, who believe any new development would erase the area’s history, saw the move as political, and Lifta quickly became a flashpoint.

One of the 77 buildings still standing in Lifta after the destruction of more than 200. Photograph: Stefanie Glinski/The Guardia

Currently on Unesco’s tentative list, meaning it could become a world heritage site, the fate of the village has even divided Israeli authorities, because it has long been a place of escape for thousands of Jerusalem residents.

“We weren’t informed about the publication of this tender and didn’t approve it. The mayor of Jerusalem asked all the relevant authorities to reconsider the construction plan,” a Jerusalem municipality spokesperson said.

The land authority said it had published tenders for housing, employment and tourism “in accordance with the availability of land and the statutory approval of the plans”. Though unusual, it is legally able to proceed with the tender without the municipality’s approval.

Currently on Unesco’s tentative list, meaning it could become a world heritage site, the fate of the village has even divided Israeli authorities, because it has long been a place of escape for thousands of Jerusalem residents.

“We weren’t informed about the publication of this tender and didn’t approve it. The mayor of Jerusalem asked all the relevant authorities to reconsider the construction plan,” a Jerusalem municipality spokesperson said.

The land authority said it had published tenders for housing, employment and tourism “in accordance with the availability of land and the statutory approval of the plans”. Though unusual, it is legally able to proceed with the tender without the municipality’s approval.

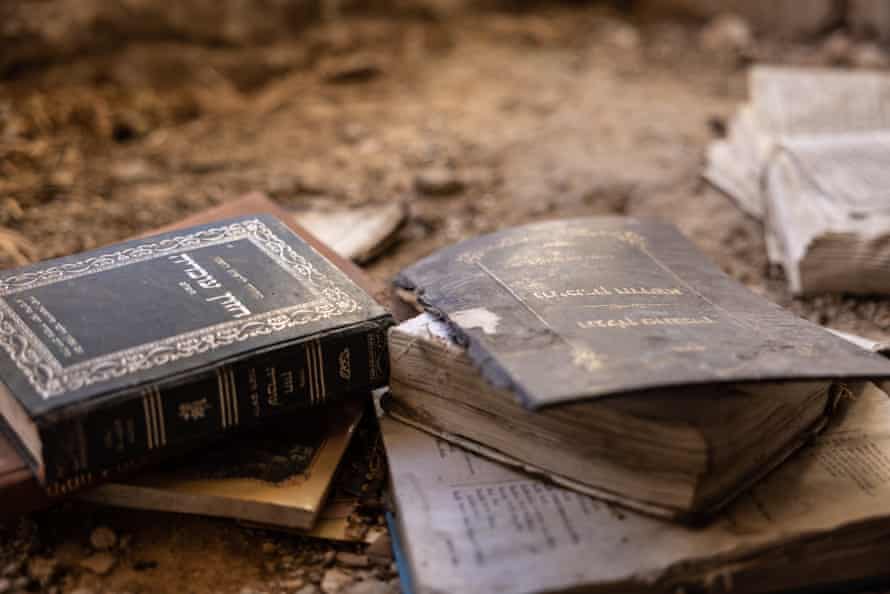

Religious books scattered on the floor in one of Lifta’s houses. Former residents say people have previously gathered there for religious studies. Photograph: Stefanie Glinski/The Guardian

As part of its push for development, the land authority commissioned the antiquities authority, an independent government body, to carry out a full survey of the area. The survey was completed in 2016 but was not publicly released until this May.

“On that survey, you can’t develop Lifta,” said the Palestinian-British architect Antoine Raffoul. “The village’s natural spring is even mentioned in the Bible and a settlement existed in the area as early as the Iron Age. It has developed over thousands of years and deserves preservation. This is a cultural war we’re fighting.”

People living in Jerusalem have described Lifta as an open-air museum, with 77 buildings still standing.

Advertisement

At its height, it was home to more than 2,500 people, had orchards, several olive presses, two coffee houses, a mosque and a winepress.

More than 200 buildings have been destroyed since 1948. Most of those who lived there fled to neighbouring Jordan or other Palestinian cities in the West Bank.

As part of its push for development, the land authority commissioned the antiquities authority, an independent government body, to carry out a full survey of the area. The survey was completed in 2016 but was not publicly released until this May.

“On that survey, you can’t develop Lifta,” said the Palestinian-British architect Antoine Raffoul. “The village’s natural spring is even mentioned in the Bible and a settlement existed in the area as early as the Iron Age. It has developed over thousands of years and deserves preservation. This is a cultural war we’re fighting.”

People living in Jerusalem have described Lifta as an open-air museum, with 77 buildings still standing.

Advertisement

At its height, it was home to more than 2,500 people, had orchards, several olive presses, two coffee houses, a mosque and a winepress.

More than 200 buildings have been destroyed since 1948. Most of those who lived there fled to neighbouring Jordan or other Palestinian cities in the West Bank.

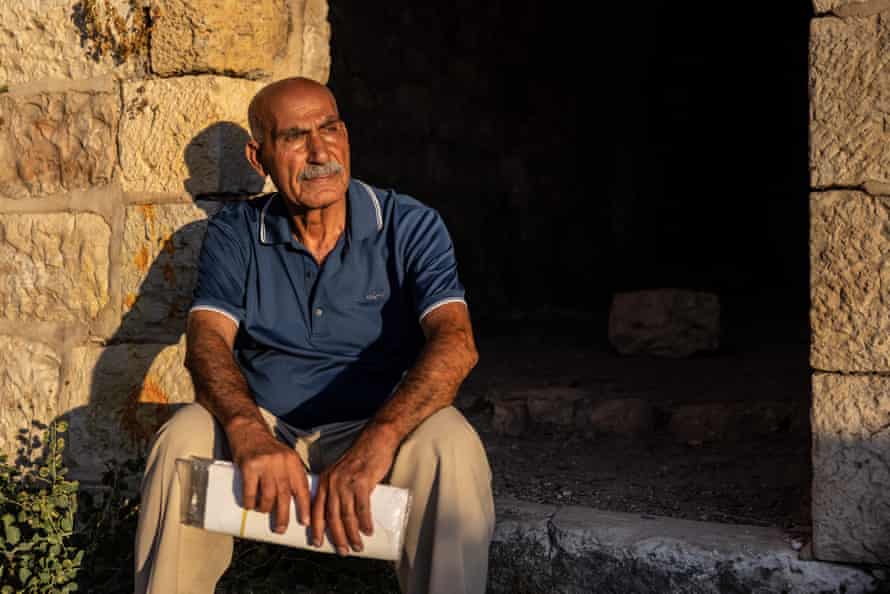

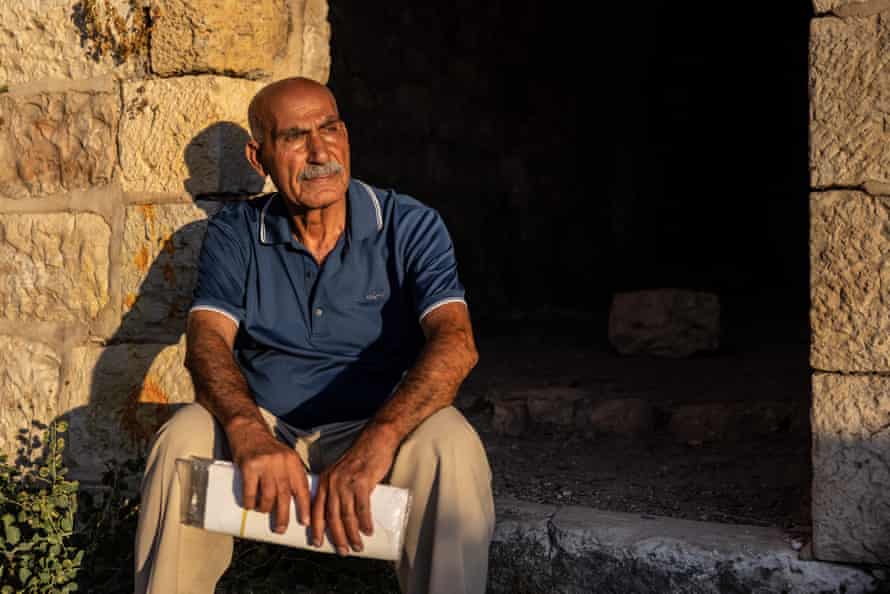

Yacoub Odeh, an 81-year-old who grew up in Lifta, sits outside what was once the village’s mosque. Photograph: Stefanie Glinski/The Guardian

“Villagers used to gather near the spring in the evenings, telling stories, drinking coffee, even dancing together. We shared happiness and, when one of the villagers died, we also shared sadness. The village was alive,” said Yacoub Odeh, an 81-year-old former resident who was born in Lifta.

“This is painful for me. When we were evicted, people scattered in all directions. We lost track of each other, of our community,” he said as he stood quietly near the ruins of what was once his family home.

Odeh, who lives in a suburb of Jerusalem, said he hoped his village might be turned into a heritage site instead. He visits several times a week, driving up the hill in his battered car.

Daphna Golan-Agnon, a Hebrew University human rights professor and Lifta activist, said the antiquities authority’s survey – which has taken archaeology, history, architecture, wildlife and ecology into account – showed clearly that Lifta can be preserved.

“It’s amazing that after more than 70 years of abandonment, the village is still standing so beautifully, even with many of the houses’ roofs destroyed. We ask for the buildings to be stabilised and are willing to help fundraise if cost is an issue.”

“Villagers used to gather near the spring in the evenings, telling stories, drinking coffee, even dancing together. We shared happiness and, when one of the villagers died, we also shared sadness. The village was alive,” said Yacoub Odeh, an 81-year-old former resident who was born in Lifta.

“This is painful for me. When we were evicted, people scattered in all directions. We lost track of each other, of our community,” he said as he stood quietly near the ruins of what was once his family home.

Odeh, who lives in a suburb of Jerusalem, said he hoped his village might be turned into a heritage site instead. He visits several times a week, driving up the hill in his battered car.

Daphna Golan-Agnon, a Hebrew University human rights professor and Lifta activist, said the antiquities authority’s survey – which has taken archaeology, history, architecture, wildlife and ecology into account – showed clearly that Lifta can be preserved.

“It’s amazing that after more than 70 years of abandonment, the village is still standing so beautifully, even with many of the houses’ roofs destroyed. We ask for the buildings to be stabilised and are willing to help fundraise if cost is an issue.”

Children swim in Lifta’s spring. Photograph: Stefanie Glinski/The Guardian

Today, the ancient site is mostly used as a recreational park by Jews and Palestinians alike, with children swimming in the pool of the spring, older women picking cactus fruit and teenagers smoking cigarettes in the shade of trees.

Tamar Maor, 92, was one of the village’s few Jewish residents in 1948. She describes the relationships between “the Arab families” and her own as “excellent”.

“I remember the day we left,” she said. “Three or four men in khaki knocked on our door and told my mother we had to leave. They also knocked on our Arab neighbour’s door. We cried and hugged and cried more, but promised each other we’d return. We all left the next day.”

Maor’s family went back temporarily but found most houses damaged, their Arab friends gone and their village no longer liveable.

Today, the ancient site is mostly used as a recreational park by Jews and Palestinians alike, with children swimming in the pool of the spring, older women picking cactus fruit and teenagers smoking cigarettes in the shade of trees.

Tamar Maor, 92, was one of the village’s few Jewish residents in 1948. She describes the relationships between “the Arab families” and her own as “excellent”.

“I remember the day we left,” she said. “Three or four men in khaki knocked on our door and told my mother we had to leave. They also knocked on our Arab neighbour’s door. We cried and hugged and cried more, but promised each other we’d return. We all left the next day.”

Maor’s family went back temporarily but found most houses damaged, their Arab friends gone and their village no longer liveable.

Lifta is known for its domed stone houses with arched windows, built during the early Ottoman empire. Photograph: Stefanie Glinski/The Guardian

Decades later, and shortly before the tender’s release, many of Lifta’s houses have a small Palestinian flag painted inside their doorframes and a single statement, or wish, inscribed below in Arabic: “We will return.”

Decades later, and shortly before the tender’s release, many of Lifta’s houses have a small Palestinian flag painted inside their doorframes and a single statement, or wish, inscribed below in Arabic: “We will return.”

No comments:

Post a Comment