Politicians, not scientists, lead the hydroxychloroquine discussion

Posted 17 June 2020

Photo of Jair Bolsonaro and Narendra Modi by Palácio do Planalto (CC BY 2.0). Photo of Donald Trump by Gage Skidmore (CC BY-SA 3.0). Image remix by Georgia Popplewell.

As COVID-19 spread around the world in early 2020, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), an anti-malaria drug touted as a miracle cure by the US president Donald Trump, triggered a global, polarized debate with significant geopolitical impacts.

The debate around HCQ in the United States was widely covered in international English-language media, but the controversy swirling around the same drug in Brazil and India — two countries where partisanship is equally as rife — has received less attention.

The countries deployed drastically different responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. India declared a national lockdown on March 25, while Brazil never instituted one. In both countries, however, the HCQ debate quickly became a useful rhetorical lever to push nationalist positions. Even as HCQ's efficacy remained unproven, its use was aggressively touted by Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro and Indian prime minister Narendra Modi.

HCQ has now been removed by the US Federal Drug Administration's list of drugs approved for use against COVID-19, yet both India and Brazil continue to recommend its use as a treatment.

Brazil and India have plenty in common. Both are middle-income economies and large democracies that have elected far-right nationalist leaders in the past decade. Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have galvanized support around Hindu-nationalist sentiment in an attempt to raise India’s profile as an international powerhouse. Brazil elected Bolsonaro president in 2018 on a platform that blended tough-on-crime-and-corruption rhetoric with hardline cultural conservatism and ultra-liberal economic policy that promised sweeping labor and environmental deregulation.

India, the world's largest manufacturer of HCQ, was in a unique position to exploit the opening provided by Trump and his supporters’ championing of the drug. The Indian government had initially banned the exportation of HCQ, then reversed the ban and began supplying the drug on a large scale to the US, Brazil, Morocco, and other countries.

In Brazil — a modest manufacturer of the drug in comparison to India — Bolsanaro ordered an Armed Forces’ pharmaceutical lab to boost its production of HCQ three days after Trump first called the drug a “game-changer.” By mid-April, the lab had increased its output of the drug a hundredfold.

Bolsonaro began aggressively promoting HCQ as a miracle cure, causing the resignation of two health ministers between April and May. In April, Twitter deleted a video post by Bolsonaro in which he defends the drug's use at a political rally. Twitter asserted that the tweet violated the platform’s rules, marking the first time the company deleted a post by a Brazilian head of state. In May, Bolsonaro said in one of his weekly live broadcasts on social media that “if you’re right-wing, you take chloroquine; if you’re left-wing, you take Tubaína” (Tubaína is a soft-drink popular in some Brazilian regions).

Bolsonaro, Modi, and Trump all employ conspiracy narratives and seek enemies or traitors in order to energize their supporters. In both India and Brazil, as in the US, these narratives hinge on unproven claims of scientific evidence that HCQ is effective against COVID-19. The imagined enemy in these narratives is the World Health Organization (WHO) and China, which are accused of suppressing this information in collusion with social media companies and the media. The beneficiaries of this alleged scheme include big pharmaceutical companies, who are said to be poised to produce a new treatment that is sure to be both expensive and lucrative.

The idea that there’s a miracle cure for a disease that has killed over 400,000 people, and that a few powerful but morally dubious elements are preventing people from accessing it, allows these leaders to them cast themselves in the role of saviors fighting against an evil system.

Brazil’s selective science

A favorite tactic of Bolsonaro’s supporters is amplifying the opinions of the handful of scientists and doctors who defend the early administration of hydroxychloroquine to COVID-19 patients.

When Exame, a well-established Brazilian business magazine, reported on a study conducted by a private hospital network that allegedly “cured 300 COVID-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine,” the article was shared extensively on social media in right-wing circles. According to the Exame story, Brazilian hospital Prevent Senior administered HCQ to 500 COVID-19 patients, of whom 300 recovered from the disease.

Similarly to the discredited French study that sparked the HCQ debate in the first place, the Prevent Senior trial was neither randomized nor double-blind, the gold standard for clinical drug trials. Many experts pointed to problems with the study’s sample.

Two weeks later, Brazil’s National Ethics Board in Medical Research ordered the suspension of the study, on the grounds that Prevent Senior had not obtained prior authorization to begin the research. Its directors will be investigated by the board for misconduct.

None of that prevented Carla Zambelli, one of Bolsonaro’s closest allies in Congress, from promoting the study on Twitter and on Facebook, where the post was shared over 6,800 times.

Social media posts by Brazilian federal deputy and member of Congress Carla Zambelli, promoting an article highlighting a discredited research study on the efficacy of HCQ in treating COVID-19. The post attracted hundreds of comments and was shared thousands of times on both platforms.

An English-language text detailing the study was also published after the suspension on Medicine Uncensored, a portal frequently mentioned by supporters of Trump and Bolsonaro in Brazil and the United States.

Other favored targets of Bolsonaro supporters are medical studies concluding that HCQ is ineffective or unsafe for treating COVID-19. On social media, death threats were leveled at the authors of a study conducted in Manaus, one of the cities hardest hit by the pandemic, which compared the effects of different dosages of HCQ on patients with severe symptoms. After the authors published a preliminary finding that HCQ could be lethal in severely ill patients on the online portal medRxiv, the New York Times picked up the story, which drew widespread attention to the study in Brazil. Bolsonaro supporters began digging through the researchers’ social media profiles, allegedly finding evidence showing the researchers’ support for leftist politicians.

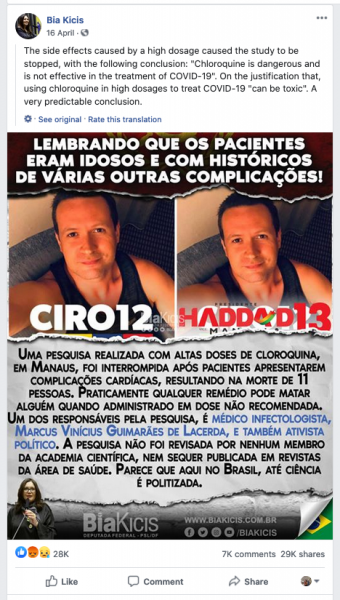

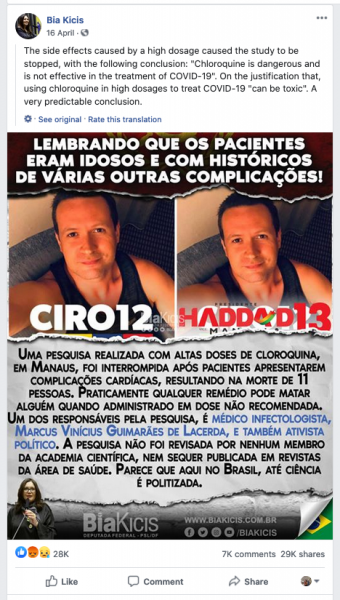

On an April 16 Facebook post by federal deputy and Bolsonaro ally Bia Kicis criticizing the study, many of the commenters call for one of the researchers to be arrested or killed for “murdering people on purpose in order to disprove HCQ.” The post has been shared over 29,000 times.

A photo of one of the researchers of the Manaus medical study is shown in this Facebook post by Bolsonaro ally Bia Kicis. Many commenting on the post called for the researcher to be arrested or killed.

Conexão Política, a pro-Bolsonaro website, added fuel to the fire when it published a story with screenshots and links to the researchers’ social media profiles. According to the story: “Everything seems to suggest that the research was financed by federal funds allocated by leftist senators, and it was also known by the former Minister of Health Luiz Henrique Mandetta, who at a press conference on Wednesday (April 15) cited the clinical trial by political militants of Manaus, without criticizing or denouncing the irresponsibility of leftist activist researchers.”

India’s diplomatic lever

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government has trumpeted India’s massive exportation of HCQ as one of its great achievements. The BJP sees India’s HCQ production as an opportunity to develop soft power as well as strengthen its position in relation to its regional rival China.

In early April, Trump praised Prime Minister Narendra Modi for his leadership in the export of HCQ in a tweet and a press conference. On the same day, Bolsonaro sent Modi a letter thanking his Indian counterpart for resuming HCQ exports. Pro-BJP media and Hindu nationalist social media spaces glorified Bolsanaro’s message, which they viewed as proof of India's success in strengthening diplomatic relations between the two countries, and noted the Brazilian president’s reference to the Hindu god Hanuman.

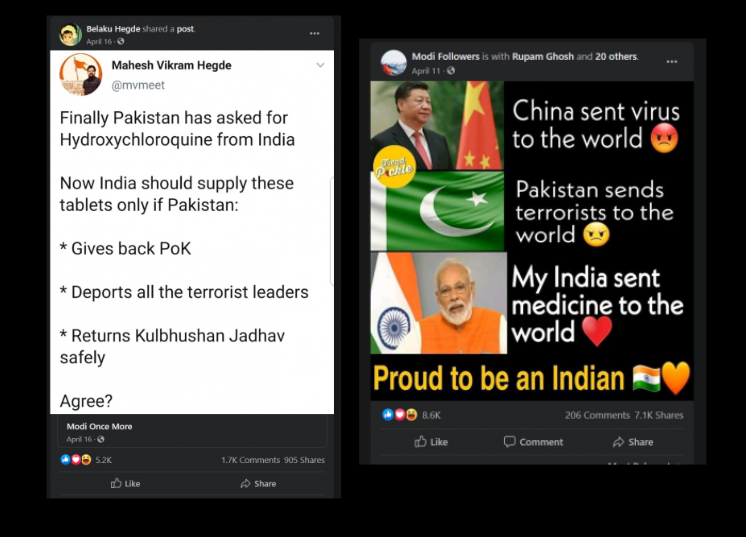

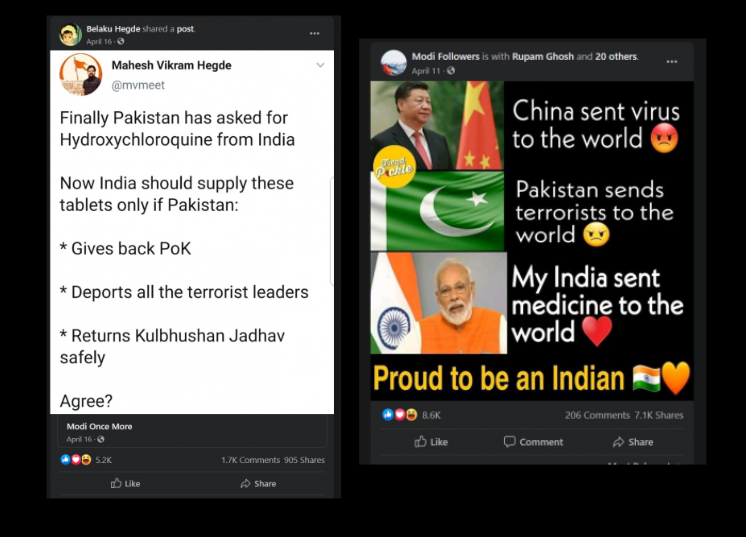

The idea that India is leading the charge against COVID-19 through its production of HCQ has resonated strongly among BJP and Modi supporters, some of whom have exploited existing tensions with China and Pakistan to further exalt India as a COVID-19 leader. One Facebook post asks whether India should make supplying Pakistan with the drug conditional. Other posts on pro-Modi Facebook groups promote the characterization of China as an aggressor who infected the world with COVID-19 and posted graphics bearing statements such as “China sent the virus to the world…My India sent medicine to the world. Proud to be an Indian.”

Popular social media posts exploiting tensions between India and Pakistan and India and China.

The WHO and China: perfect enemies

A major element of the right-wing discourse around HCQ in both Brazil and India is antagonism toward the WHO, though on this score Bolsonaro and Modi diverge in terms of approach. Bolsonaro has long disdained multilateralism, while Modi holds a more favorable, if opportunistic view, believing that multilateralism could help advance India’s national interests.

In both countries, however, a series of recent missteps by the WHO gave a boost to each leader’s agenda.

In late May, after a highly publicized study published in the prestigious Lancet medical journal concluded that HCQ increased the risk of death and cardiac complications in COVID patients, the WHO temporarily suspended trials of the drug. Ultimately, the study was retracted by its lead author, and the WHO rescinded the suspension of the clinical trials.

The WHO’s indecision, combined with the growing skirmishes at the China-India border and a more global narrative that seeks to blame China for the pandemic, triggered a surge of Indian right-wing discourse against the organization.

The day after the WHO announced the suspension, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) stated that India would continue testing HCQ in combined trials. BJP supporters applauded the ICMR’s decision, calling the WHO “incompetent” and trotting out the claim that the organization was controlled by China and big pharmaceutical companies who want to “diminish India’s global impact and economy.”

After the WHO reversed its decision, Modi supporters celebrated the organization's “caving in” to India, which they viewed as a strike against China’s attempts to diminish India’s importance in the international market.

Popular social media posts by a journalist from a pro-government news outlet and a pro-Modi Facebook group touting India's HCQ production and promoting the idea of COVID-19 as “made in China” virus.

A similar dynamic played out in Brazil. Immediately after the May 15 resignation of Nelson Taich as health minister — the second to resign since the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic — his replacement, General Eduardo Pazuello, signed a protocol recommending that Brazilian doctors use HCQ for COVID-19 patients.

Brazil's government didn't change its stance after the Lancet study appeared, and when the study was eventually retracted and the WHO apologized for having suspended solidarity trials based on it, Bolsonaristas gloated that their hostility toward the WHO was justified.

Pro-Bolsonaro social media pages and legislators have claimed that denying HCQ to COVID-19 patients is a “crime against humanity,” an assertion also made in April by US doctor Vladimir Zelenko in an interview with former Trump chief strategist Steve Bannon. Dr. Zelenko rose from obscure general practitioner to right-wing media stardom in the US for trumpeting the use of the hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin and zinc sulfate against COVID-19. He is being investigated by federal prosecutors in the US for falsely claiming that a hospital study of drugs he had promoted had won federal approval.

Two nationalisms

While Indian opposition to China stems from regional disputes and competition for global influence, in Brazil the anti-China narrative is more abstract and based on a deep ideological allegiance— some would say subservience— to the United States.

Militant anti-communism has been a staple of Brazilian right-wing politics since the 1930s, with the Bolsonaro government its most recent incarnation. Part of the current anti-communist narrative is that there is a new cold war, a global struggle between freedom— represented by the Trump’s United States— and communism— represented by China — and Brazil is simply siding with morality. This is the logic by which Bolsonaro critics, including some of Brazil’s most emblematic right-wing figures, end up being labeled as “communists” by his supporters.

The controversy surrounding hydroxychloroquine and COVID-19 is a testament to the challenge scientists face in a post-truth era. As research on effective treatments for COVID-19 continues, hydroxychloroquine stands on a precarious pedestal. It is used to advance partisan geopolitical anxieties about science and healthcare, and influences and overshadows coverage of other aspects of the pandemic.

In Brazil and India, which are experiencing a rapid decline in both democracy and public faith in the democratic process, that challenge can be particularly hard to navigate and understand.

Modi was notorious for his misrule as chief minister for the state of Gujarat, where under his tenure Muslims were targeted and killed. Bolsonaro rose up from the fringes of Brazilian Congress, where he made a career out of insulting LGBTQ+ people and praising Brazilian’s right-wing military dictatorship, which ruled from 1964 to 1985.

Both administrations have been marked by the erosion of institutions, attacks on the press, and persecution of critics. In India, religious minorities, especially Muslims, bear the brunt of that persecution, to the detriment of a multicultural and secular India enshrined in the republic's 1947 constitution. In Brazil, it is plurality of political opinion, and the social rights enshrined in the country’s progressive 1988 constitution that are most at risk.

Asteris Masouras and Alex Esenler contributed research for this story.

As COVID-19 spread around the world in early 2020, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), an anti-malaria drug touted as a miracle cure by the US president Donald Trump, triggered a global, polarized debate with significant geopolitical impacts.

The debate around HCQ in the United States was widely covered in international English-language media, but the controversy swirling around the same drug in Brazil and India — two countries where partisanship is equally as rife — has received less attention.

The countries deployed drastically different responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. India declared a national lockdown on March 25, while Brazil never instituted one. In both countries, however, the HCQ debate quickly became a useful rhetorical lever to push nationalist positions. Even as HCQ's efficacy remained unproven, its use was aggressively touted by Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro and Indian prime minister Narendra Modi.

HCQ has now been removed by the US Federal Drug Administration's list of drugs approved for use against COVID-19, yet both India and Brazil continue to recommend its use as a treatment.

Brazil and India have plenty in common. Both are middle-income economies and large democracies that have elected far-right nationalist leaders in the past decade. Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have galvanized support around Hindu-nationalist sentiment in an attempt to raise India’s profile as an international powerhouse. Brazil elected Bolsonaro president in 2018 on a platform that blended tough-on-crime-and-corruption rhetoric with hardline cultural conservatism and ultra-liberal economic policy that promised sweeping labor and environmental deregulation.

India, the world's largest manufacturer of HCQ, was in a unique position to exploit the opening provided by Trump and his supporters’ championing of the drug. The Indian government had initially banned the exportation of HCQ, then reversed the ban and began supplying the drug on a large scale to the US, Brazil, Morocco, and other countries.

In Brazil — a modest manufacturer of the drug in comparison to India — Bolsanaro ordered an Armed Forces’ pharmaceutical lab to boost its production of HCQ three days after Trump first called the drug a “game-changer.” By mid-April, the lab had increased its output of the drug a hundredfold.

Bolsonaro began aggressively promoting HCQ as a miracle cure, causing the resignation of two health ministers between April and May. In April, Twitter deleted a video post by Bolsonaro in which he defends the drug's use at a political rally. Twitter asserted that the tweet violated the platform’s rules, marking the first time the company deleted a post by a Brazilian head of state. In May, Bolsonaro said in one of his weekly live broadcasts on social media that “if you’re right-wing, you take chloroquine; if you’re left-wing, you take Tubaína” (Tubaína is a soft-drink popular in some Brazilian regions).

Bolsonaro, Modi, and Trump all employ conspiracy narratives and seek enemies or traitors in order to energize their supporters. In both India and Brazil, as in the US, these narratives hinge on unproven claims of scientific evidence that HCQ is effective against COVID-19. The imagined enemy in these narratives is the World Health Organization (WHO) and China, which are accused of suppressing this information in collusion with social media companies and the media. The beneficiaries of this alleged scheme include big pharmaceutical companies, who are said to be poised to produce a new treatment that is sure to be both expensive and lucrative.

The idea that there’s a miracle cure for a disease that has killed over 400,000 people, and that a few powerful but morally dubious elements are preventing people from accessing it, allows these leaders to them cast themselves in the role of saviors fighting against an evil system.

Brazil’s selective science

A favorite tactic of Bolsonaro’s supporters is amplifying the opinions of the handful of scientists and doctors who defend the early administration of hydroxychloroquine to COVID-19 patients.

When Exame, a well-established Brazilian business magazine, reported on a study conducted by a private hospital network that allegedly “cured 300 COVID-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine,” the article was shared extensively on social media in right-wing circles. According to the Exame story, Brazilian hospital Prevent Senior administered HCQ to 500 COVID-19 patients, of whom 300 recovered from the disease.

Similarly to the discredited French study that sparked the HCQ debate in the first place, the Prevent Senior trial was neither randomized nor double-blind, the gold standard for clinical drug trials. Many experts pointed to problems with the study’s sample.

Two weeks later, Brazil’s National Ethics Board in Medical Research ordered the suspension of the study, on the grounds that Prevent Senior had not obtained prior authorization to begin the research. Its directors will be investigated by the board for misconduct.

None of that prevented Carla Zambelli, one of Bolsonaro’s closest allies in Congress, from promoting the study on Twitter and on Facebook, where the post was shared over 6,800 times.

Social media posts by Brazilian federal deputy and member of Congress Carla Zambelli, promoting an article highlighting a discredited research study on the efficacy of HCQ in treating COVID-19. The post attracted hundreds of comments and was shared thousands of times on both platforms.

An English-language text detailing the study was also published after the suspension on Medicine Uncensored, a portal frequently mentioned by supporters of Trump and Bolsonaro in Brazil and the United States.

Other favored targets of Bolsonaro supporters are medical studies concluding that HCQ is ineffective or unsafe for treating COVID-19. On social media, death threats were leveled at the authors of a study conducted in Manaus, one of the cities hardest hit by the pandemic, which compared the effects of different dosages of HCQ on patients with severe symptoms. After the authors published a preliminary finding that HCQ could be lethal in severely ill patients on the online portal medRxiv, the New York Times picked up the story, which drew widespread attention to the study in Brazil. Bolsonaro supporters began digging through the researchers’ social media profiles, allegedly finding evidence showing the researchers’ support for leftist politicians.

On an April 16 Facebook post by federal deputy and Bolsonaro ally Bia Kicis criticizing the study, many of the commenters call for one of the researchers to be arrested or killed for “murdering people on purpose in order to disprove HCQ.” The post has been shared over 29,000 times.

A photo of one of the researchers of the Manaus medical study is shown in this Facebook post by Bolsonaro ally Bia Kicis. Many commenting on the post called for the researcher to be arrested or killed.

Conexão Política, a pro-Bolsonaro website, added fuel to the fire when it published a story with screenshots and links to the researchers’ social media profiles. According to the story: “Everything seems to suggest that the research was financed by federal funds allocated by leftist senators, and it was also known by the former Minister of Health Luiz Henrique Mandetta, who at a press conference on Wednesday (April 15) cited the clinical trial by political militants of Manaus, without criticizing or denouncing the irresponsibility of leftist activist researchers.”

India’s diplomatic lever

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government has trumpeted India’s massive exportation of HCQ as one of its great achievements. The BJP sees India’s HCQ production as an opportunity to develop soft power as well as strengthen its position in relation to its regional rival China.

In early April, Trump praised Prime Minister Narendra Modi for his leadership in the export of HCQ in a tweet and a press conference. On the same day, Bolsonaro sent Modi a letter thanking his Indian counterpart for resuming HCQ exports. Pro-BJP media and Hindu nationalist social media spaces glorified Bolsanaro’s message, which they viewed as proof of India's success in strengthening diplomatic relations between the two countries, and noted the Brazilian president’s reference to the Hindu god Hanuman.

The idea that India is leading the charge against COVID-19 through its production of HCQ has resonated strongly among BJP and Modi supporters, some of whom have exploited existing tensions with China and Pakistan to further exalt India as a COVID-19 leader. One Facebook post asks whether India should make supplying Pakistan with the drug conditional. Other posts on pro-Modi Facebook groups promote the characterization of China as an aggressor who infected the world with COVID-19 and posted graphics bearing statements such as “China sent the virus to the world…My India sent medicine to the world. Proud to be an Indian.”

Popular social media posts exploiting tensions between India and Pakistan and India and China.

The WHO and China: perfect enemies

A major element of the right-wing discourse around HCQ in both Brazil and India is antagonism toward the WHO, though on this score Bolsonaro and Modi diverge in terms of approach. Bolsonaro has long disdained multilateralism, while Modi holds a more favorable, if opportunistic view, believing that multilateralism could help advance India’s national interests.

In both countries, however, a series of recent missteps by the WHO gave a boost to each leader’s agenda.

In late May, after a highly publicized study published in the prestigious Lancet medical journal concluded that HCQ increased the risk of death and cardiac complications in COVID patients, the WHO temporarily suspended trials of the drug. Ultimately, the study was retracted by its lead author, and the WHO rescinded the suspension of the clinical trials.

The WHO’s indecision, combined with the growing skirmishes at the China-India border and a more global narrative that seeks to blame China for the pandemic, triggered a surge of Indian right-wing discourse against the organization.

The day after the WHO announced the suspension, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) stated that India would continue testing HCQ in combined trials. BJP supporters applauded the ICMR’s decision, calling the WHO “incompetent” and trotting out the claim that the organization was controlled by China and big pharmaceutical companies who want to “diminish India’s global impact and economy.”

After the WHO reversed its decision, Modi supporters celebrated the organization's “caving in” to India, which they viewed as a strike against China’s attempts to diminish India’s importance in the international market.

Popular social media posts by a journalist from a pro-government news outlet and a pro-Modi Facebook group touting India's HCQ production and promoting the idea of COVID-19 as “made in China” virus.

A similar dynamic played out in Brazil. Immediately after the May 15 resignation of Nelson Taich as health minister — the second to resign since the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic — his replacement, General Eduardo Pazuello, signed a protocol recommending that Brazilian doctors use HCQ for COVID-19 patients.

Brazil's government didn't change its stance after the Lancet study appeared, and when the study was eventually retracted and the WHO apologized for having suspended solidarity trials based on it, Bolsonaristas gloated that their hostility toward the WHO was justified.

Pro-Bolsonaro social media pages and legislators have claimed that denying HCQ to COVID-19 patients is a “crime against humanity,” an assertion also made in April by US doctor Vladimir Zelenko in an interview with former Trump chief strategist Steve Bannon. Dr. Zelenko rose from obscure general practitioner to right-wing media stardom in the US for trumpeting the use of the hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin and zinc sulfate against COVID-19. He is being investigated by federal prosecutors in the US for falsely claiming that a hospital study of drugs he had promoted had won federal approval.

Two nationalisms

While Indian opposition to China stems from regional disputes and competition for global influence, in Brazil the anti-China narrative is more abstract and based on a deep ideological allegiance— some would say subservience— to the United States.

Militant anti-communism has been a staple of Brazilian right-wing politics since the 1930s, with the Bolsonaro government its most recent incarnation. Part of the current anti-communist narrative is that there is a new cold war, a global struggle between freedom— represented by the Trump’s United States— and communism— represented by China — and Brazil is simply siding with morality. This is the logic by which Bolsonaro critics, including some of Brazil’s most emblematic right-wing figures, end up being labeled as “communists” by his supporters.

The controversy surrounding hydroxychloroquine and COVID-19 is a testament to the challenge scientists face in a post-truth era. As research on effective treatments for COVID-19 continues, hydroxychloroquine stands on a precarious pedestal. It is used to advance partisan geopolitical anxieties about science and healthcare, and influences and overshadows coverage of other aspects of the pandemic.

In Brazil and India, which are experiencing a rapid decline in both democracy and public faith in the democratic process, that challenge can be particularly hard to navigate and understand.

Modi was notorious for his misrule as chief minister for the state of Gujarat, where under his tenure Muslims were targeted and killed. Bolsonaro rose up from the fringes of Brazilian Congress, where he made a career out of insulting LGBTQ+ people and praising Brazilian’s right-wing military dictatorship, which ruled from 1964 to 1985.

Both administrations have been marked by the erosion of institutions, attacks on the press, and persecution of critics. In India, religious minorities, especially Muslims, bear the brunt of that persecution, to the detriment of a multicultural and secular India enshrined in the republic's 1947 constitution. In Brazil, it is plurality of political opinion, and the social rights enshrined in the country’s progressive 1988 constitution that are most at risk.

Asteris Masouras and Alex Esenler contributed research for this story.

No comments:

Post a Comment