Dark matter travelling through stars could produce potentially detectable shock waves

Dark matter, a hypothetical material that does not absorb, emit or reflect light, is thought to account for over 80 percent of the matter in the universe. While many studies have indirectly hinted at its existence, so far, physicists have been unable to directly detect dark matter and thus to confidently determine what it consists of.

One factor that makes searching for dark matter particularly challenging is that very little is known about its possible mass and composition. This means that dark matter searches are based on great part on hypotheses and theoretical assumptions.

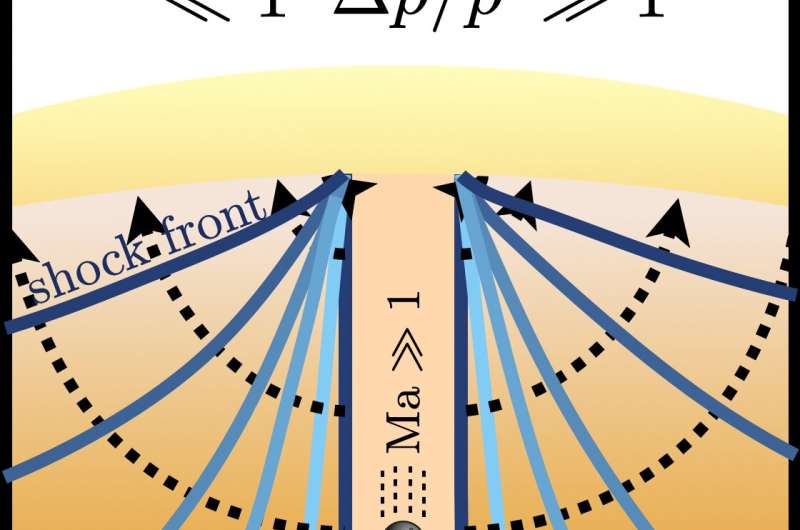

Researchers at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Université Paris Saclay have recently carried out a theoretical study that could introduce a new way of searching for dark matter. Their paper, published in Physical Review Letters, shows that when macroscopic dark matter travels through a star, it could produce shock waves that might reach the star's surface. These waves could in turn lead to distinctive and transient optical, UV and X-ray emissions that might be detectable by sophisticated telescopes.

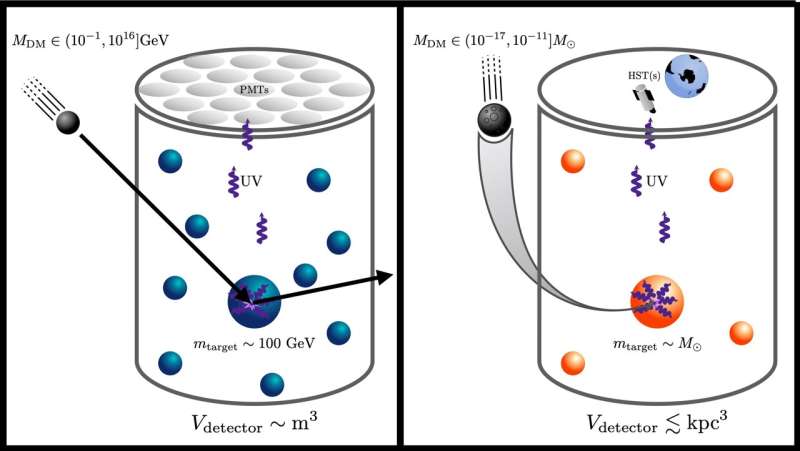

"Most experiments have searched for dark matter made of separate particles, each about as heavy as an atomic nucleus, or clumps about as massive as planets or stars," Kevin Zhou, one of the researchers who carried out the study, told Phys.org. "We were interested in the intermediate case of asteroid-sized dark matter, which had been thought to be hard to test experimentally, since dark asteroids would be too rare to impact Earth, but too small to see in space."

Initially, Zhou and his colleagues started exploring the possibility that the heat produced during the impact between a dark matter asteroid and an ordinary star could result in the star exploding. This hypothesis was based on past studies suggesting that energy deposition can sometimes trigger supernova in white dwarfs. After a few weeks of calculations and discussions, however, the team realized that the impact between a dark matter asteroid and an ordinary star would most likely not lead to an explosion, as ordinary stars are more stable than white dwarfs.

"We had a hunch that the energy produced by such a collision should be visible somehow, so we brainstormed for a few months, trying and tossing out idea after idea," Zhou explained. "Finally, we realized that the shock waves generated by the dark asteroid's travel through the star were the most promising signature."

Shock waves are sharp signals that are produced when an object is moving faster than the speed of sound. For instance, a supersonic aircraft produces a sonic boom, which can be heard from the Earth's surface even when it is flying miles above it.

Similarly, Zhou and his colleagues predicted that the shock waves produced by dark asteroids deep inside a star could reach a star's surface. This would in turn result in a short-lived hot spot that could be detected using telescopes that can examine the UV spectrum.

"We're excited that we identified a powerful new way to search for a kind of dark matter thought to be hard to test, using telescopes that we already have in an unexpected way," Zhou said. "The most powerful UV telescope is the Hubble space telescope, but since stellar shock events are transients, it helps to be able to monitor more of the sky at once."

The recent study follows a growing trend within the astrophysics community to use astronomical objects as enormous dark matter detectors. This promising approach to searching for dark matter unites the fields of particle physics and astrophysics, bringing these two communities closer together.

In the future, the recent work by this team of researchers could inspire engineers to build new and smaller UV telescopes that can observe wider parts of the universe. A similar telescope, dubbed ULTRASAT, is already set to be released in 2024. Using this telescope, physicists could try searching for dark matter by examining stellar surfaces. In their next works, the researchers themselves plan to try to detect potential dark asteroid impact events using UV telescope data.

"The ideal case would be to use the Hubble space telescope to monitor a large globular cluster in the UV," Zhou said. "It would also be interesting to consider dark asteroids impacting other astronomical objects. Since our work, there have been papers by others considering impacts on neutron stars and red giants, but there are probably even more promising ideas in this direction that nobody has thought of yet."Physicist seeks to understand dark matter with Webb Telescope

More information: Anirban Das et al, Stellar Shocks from Dark Matter Asteroid Impacts, Physical Review Letters (2022). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.128.021101

Journal information: Physical Review Letters

© 2022 Science X Network

NASA Proposes a Way That Dark Matter’s Influence Could Be Directly Observed

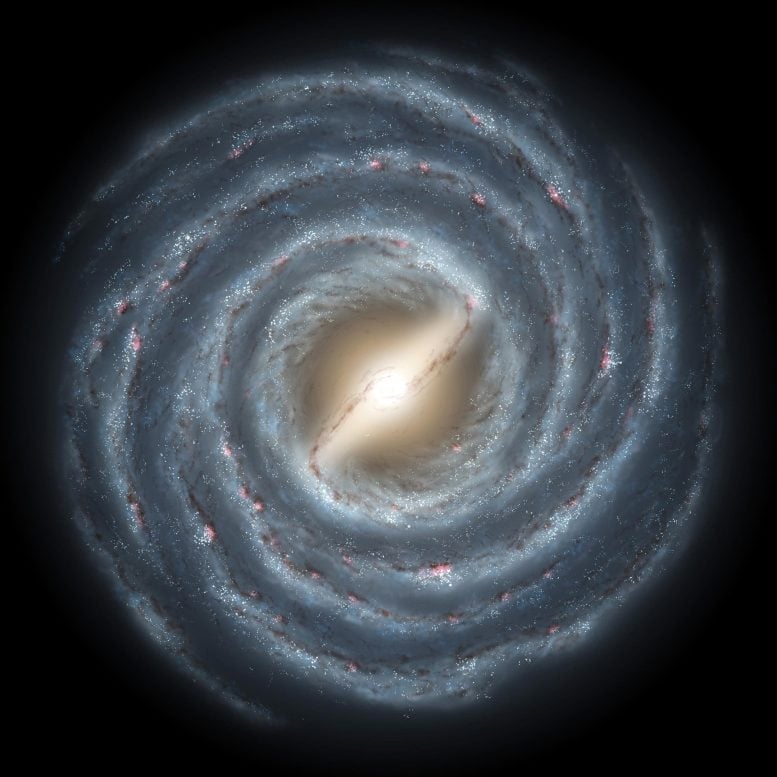

This artist’s rendering shows a view of our own Milky Way Galaxy and its central bar as it might appear if viewed from above. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (SSC)

How Dark Matter Could Be Measured in the Solar System

Pictures of the Milky Way show billions of stars arranged in a spiral pattern radiating out from the center, with illuminated gas in between. But our eyes can only glimpse the surface of what holds our galaxy together. About 95 percent of the mass of our galaxy is invisible and does not interact with light. It is made of a mysterious substance called dark matter, which has never been directly measured.

Now, a new study calculates how dark matter’s gravity affects objects in our solar system, including spacecraft and distant comets. It also proposes a way that dark matter’s influence could be directly observed with a future experiment. The article is published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

“We’re predicting that if you get out far enough in the solar system, you actually have the opportunity to start measuring the dark matter force,” said Jim Green, study co-author and advisor to NASA’s Office of the Chief Scientist. “This is the first idea of how to do it and where we would do it.”

Dark matter in our backyard

Here on Earth, our planet’s gravity keeps us from flying out of our chairs, and the Sun’s gravity keeps our planet orbiting on a 365-day schedule. But the farther from the Sun a spacecraft flies, the less it feels the Sun’s gravity, and the more it feels a different source of gravity: that of the matter from the rest of the galaxy, which is mostly dark matter. The mass of our galaxy’s 100 billion stars is minuscule compared to estimates of the Milky Way’s dark matter content.

To understand the influence of dark matter in the solar system, lead study author Edward Belbruno calculated the “galactic force,” the overall gravitational force of normal matter combined with dark matter from the entire galaxy. He found that in the solar system, about 45 percent of this force is from dark matter and 55 percent is from normal, so-called “baryonic matter.” This suggests a roughly half-and-half split between the mass of dark matter and normal matter in the solar system.

“I was a bit surprised by the relatively small contribution of the galactic force due to dark matter felt in our solar system as compared to the force due to the normal matter,” said Belbruno, mathematician and astrophysicist at Princeton University and Yeshiva University. “This is explained by the fact most of dark matter is in the outer parts of our galaxy, far from our solar system.”

A large region called a “halo” of dark matter encircles the Milky Way and represents the greatest concentration of the dark matter of the galaxy. There is little to no normal matter in the halo. If the solar system were located at a greater distance from the center of the galaxy, it would feel the effects of a larger proportion of dark matter in the galactic force because it would be closer to the dark matter halo, the authors said.

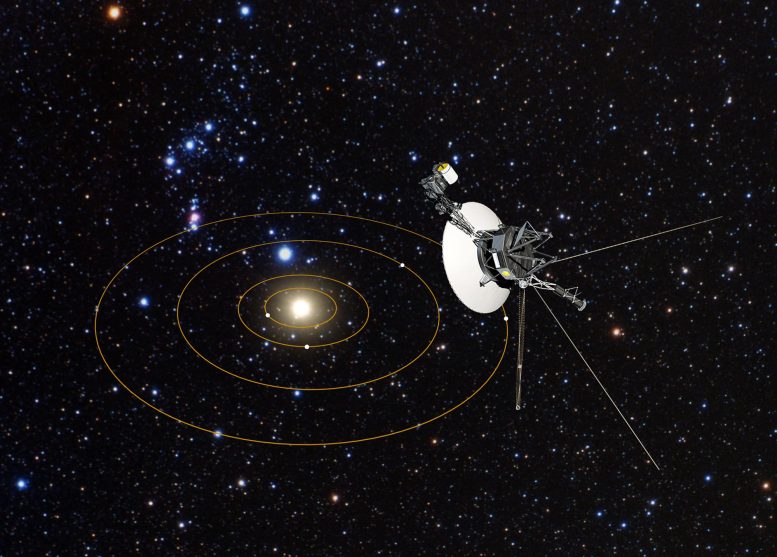

In this artist’s conception, NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft has a bird’s-eye view of the solar system. The circles represent the orbits of the major outer planets: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 visited the planets Jupiter and Saturn. The spacecraft is now more than 14 billion miles from Earth, making it the farthest human-made object ever built. In fact, Voyager 1 is now zooming through interstellar space, the region between the stars that is filled with gas, dust, and material recycled from dying stars. Credit: NASA, ESA, and G. Bacon (STScI)

How dark matter may influence spacecraft

Green and Belbruno predict that dark matter’s gravity ever so slightly interacts with all of the spacecraft that NASA has sent on paths that lead out of the solar system, according to the new study.

“If spacecraft move through the dark matter long enough, their trajectories are changed, and this is important to take into consideration for mission planning for certain future missions,” Belbruno said.

Such spacecraft may include the retired Pioneer 10 and 11 probes that launched in 1972 and 1973, respectively; the Voyager 1 and 2 probes that have been exploring for more than 40 years and have entered interstellar space; and the New Horizons spacecraft that has flown by Pluto and Arrokoth in the Kuiper Belt.

But it’s a tiny effect. After traveling billions of miles, the path of a spacecraft like Pioneer 10 would only deviate by about 5 feet (1.6 meters) due to the influence of dark matter. “They do feel the effect of dark matter, but it’s so small, we can’t measure it,” Green said.

Where does the galactic force take over?

At a certain distance from the Sun, the galactic force becomes more powerful than the pull of the Sun, which is made of normal matter. Belbruno and Green calculated that this transition happens at around 30,000 astronomical units, or 30,000 times the distance from Earth to the Sun. That is well beyond the distance of Pluto, but still inside the Oort Cloud, a swarm of millions of comets that surrounds the solar system and extends out to 100,000 astronomical units.

This means that dark matter’s gravity could have played a role in the trajectory of objects like ‘Oumuamua, the cigar-shaped comet or asteroid that came from another star system and passed through the inner solar system in 2017. Its unusually fast speed could be explained by dark matter’s gravity pushing on it for millions of years, the authors say.

If there is a giant planet in the outer reaches of the solar system, a hypothetical object called Planet 9 or Planet X that scientists have been searching for in recent years, dark matter would also influence its orbit. If this planet exists, dark matter could perhaps even push it away from the area where scientists are currently looking for it, Green and Belbruno write. Dark matter may have also caused some of the Oort Cloud comets to escape the orbit of the Sun altogether.

Could dark matter’s gravity be measured?

To measure the effects of dark matter in the solar system, a spacecraft wouldn’t necessarily have to travel that far. At a distance of 100 astronomical units, a spacecraft with the right experiment could help astronomers measure the influence of dark matter directly, Green and Belbruno said.

Specifically, a spacecraft equipped with radioisotope power, a technology that has allowed Pioneer 10 and 11, the Voyagers, and New Horizon to fly very far from the Sun, may be able to make this measurement. Such a spacecraft could carry a reflective ball and drop it at an appropriate distance. The ball would feel only galactic forces, while the spacecraft would experience a thermal force from the decaying radioactive element in its power system, in addition to the galactic forces. Subtracting out the thermal force, researchers could then look at how the galactic force relates to deviations in the respective trajectories of the ball and the spacecraft. Those deviations would be measured with a laser as the two objects fly parallel to one another.

A proposed mission concept called Interstellar Probe, which aims to travel to about 500 astronomical units from the Sun to explore that uncharted environment, is one possibility for such an experiment.

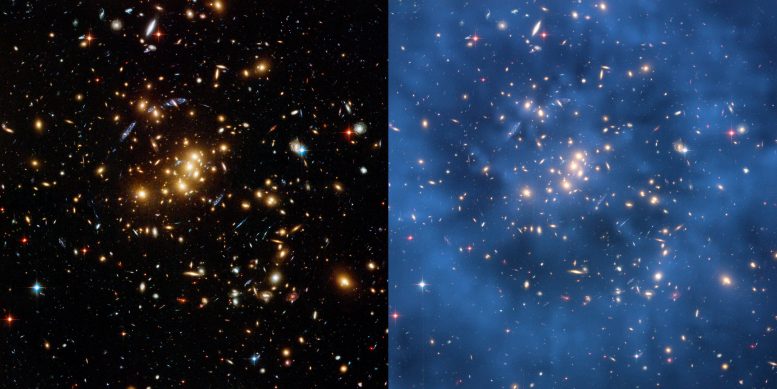

Two views from Hubble of the massive galaxy cluster Cl 0024+17 (ZwCl 0024+1652) are shown. To the left is the view in visible-light with odd-looking blue arcs appearing among the yellowish galaxies. These are the magnified and distorted images of galaxies located far behind the cluster. Their light is bent and amplified by the immense gravity of the cluster in a process called gravitational lensing. To the right, a blue shading has been added to indicate the location of invisible material called dark matter that is mathematically required to account for the nature and placement of the gravitationally lensed galaxies that are seen. Credit: NASA, ESA, M.J. Jee and H. Ford (Johns Hopkins University)

More about dark matter

Dark matter as a hidden mass in galaxies was first proposed in the 1930s by Fritz Zwicky. But the idea remained controversial until the 1960s and 1970s, when Vera C. Rubin and colleagues confirmed that the motions of stars around their galactic centers would not follow the laws of physics if only normal matter were involved. Only a gigantic hidden source of mass can explain why stars at the outskirts of spiral galaxies like ours move as quickly as they do.

Today, the nature of dark matter is one of the biggest mysteries in all of astrophysics. Powerful observatories like the Hubble Space Telescope and the Chandra X-Ray Observatory have helped scientists begin to understand the influence and distribution of dark matter in the universe at large. Hubble has explored many galaxies whose dark matter contributes to an effect called “lensing,” where gravity bends space itself and magnifies images of more distant galaxies.

Astronomers will learn more about dark matter in the cosmos with the newest set of state-of-the-art telescopes. NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, which launched Dec. 25, 2021, will contribute to our understanding of dark matter by taking images and other data of galaxies and observing their lensing effects. NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, set to launch in the mid-2020s, will conduct surveys of more than a billion galaxies to look at the influence of dark matter on their shapes and distributions.

The European Space Agency’s forthcoming Euclid mission, which has a NASA contribution, will also target dark matter and dark energy, looking back in time about 10 billion years to a period when dark energy began hastening the universe’s expansion. And the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, a collaboration of the National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy, and others, which is under construction in Chile, will add valuable data to this puzzle of dark matter’s true essence.

But these powerful tools are designed to look for dark matter’s strong effects across large distances, and much farther afield than in our solar system, where dark matter’s influence is so much weaker.

“If you could send a spacecraft out there to detect it, that would be a huge discovery,” Belbruno said.

Reference: “When leaving the Solar system: Dark matter makes a difference” by Edward Belbruno and James Green, 4 January 2022, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stab3781

No comments:

Post a Comment