Life onboard the ISS goes on in the wake of Russia’s attack against Ukraine, even as the space project faces an uncertain future

By Joanna Thompson on February 25, 2022

When Russia launched a full-scale military invasion of Ukraine on Thursday, the whole world was watching. But another, much smaller audience was watching, too: the seven crew members onboard the International Space Station (ISS), orbiting hundreds of kilometers above the chaos below.

Across more than two decades of continuous operations, the ISS has been a steady beacon of hope for peaceful international collaboration. The massive space habitat is the product of a remarkable partnership among five space agencies (including NASA and Russia’s national space agency Roscosmos) representing 15 participating countries. Over the years, scientific study and international friendships have flourished onboard the ISS, prompting some to petition for the project to receive a Nobel Peace Prize.

But some fear Russia’s latest attack could throw that cooperation into jeopardy. In times of geopolitical upheaval on Earth, what happens to the ISS?

According to former ISS astronauts, nationality usually takes a back seat to the more practical matters of living and working in space. “During training, you spend a lot of time together, and so you form these deep friendships,” says Leroy Chiao, who flew on the 10th expedition to the ISS in 2004.

Rick Mastracchio, a retired NASA engineer who flew on the 38th and 39th expeditions to the ISS, echoes that sentiment. “You’re there to do a very specific job, and you’re well trained,” he says. Regardless of one’s homeland or political views, “you need to get along because you’re [part of] a team.”

Chiao says that the time he spent with his cosmonaut colleagues gave him a measure of insight into the Russian perspective on geopolitics. From Russia’s viewpoint, the prospect of Ukraine joining NATO could seems like a serious threat to national security. How would the U.S. have reacted, he wonders, if Mexico and Canada had signed the Warsaw Pact before the fall of the Soviet Union? “That would make us pretty edgy, too. So, I understand where Russia’s coming from,” he says, even though he firmly disagrees with the nation’s invasion of Ukraine.

Tensions between Russia and the U.S. also ran unexpectedly high when Mastracchio was onboard the ISS. In March 2014, not long into his orbital sojourn, Russia annexed Crimea in a political move that the U.S. condemned as a “violation of international law.”

“I won’t say it affected the atmosphere, but there was some discussion,” Mastracchio says. He mentions what he recalls as the distress of one of his Russian crewmates in particular, who was purportedly fearful for his family in a nearby region of Ukraine. For Mastracchio, the memory serves as a reminder that no culture is a political monolith. “You’re representing your country from the terms of the space agencies, but you’re not representing the political aspect of it,” he says. “It’s somewhat uncomfortable when your homeland does something that maybe you’re not proud of.”

ADVERTISEMENT

So far, the U.S. and its NATO allies have pursued a policy of retaliatory sanctions targeting Russia’s economy and political leadership. Outlining the policy during a White House address, President Joe Biden noted that the sanctions will “degrade [Russia’s] aerospace industry, including their space program.”

How exactly this may affect life on the ISS remains unclear. The seven crew members currently onboard the habitat are four NASA astronauts, one German astronaut from the European Space Agency (ESA) and two Russian cosmonauts. Whatever their personal feelings, presumably the crew will continue normal operations in a “business as usual” approach. At least, that is the plan according to NASA.

“NASA continues working with all our international partners, including the State Space Corporation Roscosmos, for the ongoing safe operations of the International Space Station,” the agency wrote in an e-mailed statement. “The new export control measures will continue to allow U.S.-Russia civil space cooperation.”

Roscosmos did not respond to a request for comment. But in a series of tweets on Thursday afternoon, Roscosmos’s director general Dmitry Rogozin mocked the sanctions as foolhardy, adding that “if [the U.S.] blocks cooperation with us, who will save the ISS from an uncontrolled descent out of orbit and a fall on the United States or Europe?” Despite its threatening implications, Rogozin’s statement is, in some respects, reflective of simple facts: Russia’s Progress resupply spacecraft are currently responsible for periodically boosting the space station’s altitude, which decreases over time because of atmospheric drag. (A U.S.-built Cygnus cargo spacecraft presently docked at the station is scheduled to perform a test boost in April to demonstrate an independent capability to maintain the ISS’s altitude.)

Such comments are not terribly out of character for Rogozin, a Putin appointee. “He’s a bit of, you know, a personality,” says Asif Siddiqi, a historian at Fordham University, who specializes in Russian space activities.

When the U.S. enacted earlier rounds of sanctions after the Crimean annexation, Rogozin notoriously responded by suggesting that American astronauts could find their way to the ISS “with a trampoline.” (At the time, the U.S. was wholly dependent on sending crews to the ISS via launches of the Russian Soyuz spacecraft. Now SpaceX rockets and modules serve as U.S. crew transports, and Boeing is set to soon provide an additional domestic launch option.) Rogozin again raised hackles last year with statements implying that in 2018 NASA astronaut Serena Auñón-Chancellor drilled a tiny hole in a Soyuz vessel for purposes of sabotage. In an article by the Russian state-owned news agency TASS last year, a Russian space official again raised hackles with accusations that NASA astronaut Serena Auñón-Chancellor drilled a tiny hole in a Soyuz vessel so that she could return to Earth early. NASA has said it does not consider these allegations credible and that it stands by Auñón-Chancellor.

Although these periods of tension have strained administrative relations between Roscosmos and NASA in the past, they have never truly disrupted life on the ISS. During the height of the Crimean conflict, for example, a leaked internal memo instructed NASA employees to cease communications with their Russian colleagues. “However, there’s a little clause in that thing that says actual ISS operations will continue just as before,” Siddiqi says. He suspects a similar memo may be making the rounds now.

Even if a major ISS partner does decide to withdraw from the project, the transition may take months or even years to fully disentangle. “It’s not a simple off switch,” Siddiqi says. But unless the current political situation changes course, he does not see a future for U.S. and Russian collaboration in space beyond the ISS’s decommissioning, currently planned for 2031. NASA is already looking ahead to its ambitious Artemis program, which will partner with ESA, Japan’s space agency and the Canadian Space Agency to build an orbiting lunar outpost to support astronauts’ long-term return to the moon’s surface. Meanwhile Roscosmos has pledged to join forces with China in order to build a moon base of their own. The international schism in spaceflight seems set to grow—with the cooperation epitomized by the ISS only diminishing.

“It’s clear that this is a relationship that will not continue past a certain point,” Siddiqi says. “I can’t see it recovering from this.”

The International Space Station is run collectively by the U.S., Russia, the European Space Agency, Japan and Canada.

Published: February 25, 2022 8.46am EST

In response to these sanctions, the head of Roscosmos on the same day posted a tweet saying, among other things, “If you block cooperation with us, who will save the ISS from an uncontrolled deorbit and fall into the United States or Europe?”

The International Space Station has often stayed above the fray of geopolitics. That position is under threat.

Built and run by the U.S., Russia, Europe, Japan and Canada, the ISS has shown how countries can cooperate on major projects in space. The station has been continuously occupied for over 20 years and has hosted more than 250 people from 19 countries.

As a space policy expert, the ISS represents, to me, a high point of cooperation in space exploration. But for the current crew of two Russians, four Americans and one German, things may be getting worrisome as tensions rise between the U.S. and Russia.

Several agreements and systems are in place to make sure that the space station can function smoothly while being run by five different space agencies. As of Feb. 24, there were no announcements of unusual actions aboard the station despite the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine. But the Russian government has brought the ISS into geopolitics before and is doing so again.

Managing the ISS

What came to be known as the International Space Station was first conceived on NASA drawing boards in the early 1980s. As costs rose past initial estimates, NASA officials invited international partners from the European Space Agency, Canada and Japan to join the project.

When the Soviet Union collapsed at the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, the Russian space program found itself in dire straits, suffering from lack of funding and an exodus of engineers and program officials. To take advantage of Russian expertise in space stations and foster post-Cold War cooperation, the NASA administrator at the time, Dan Goldin, convinced the Clinton administration to bring Russia into the program that was rechristened the International Space Station.

By 1998, just prior to the launch of the first modules, Russia, the U.S. and the other international partners of the ISS entered into memorandums of understanding that spelled out how major decisions would be made and what kind of control each nation would have over various parts of the station.

The body that governs the operation of the space station is the Multilateral Coordination Board. This board has representatives from each of the space agencies involved in the ISS and is chaired by the U.S. The board operates by consensus in making decisions on things like a code of conduct for ISS crews.

Even among international partners who want to work together, consensus is not always possible. If this happens, either the chair of the board can make decisions on how to move forward or the issue can be elevated to the NASA administrator and the head of the Russian space agency, Roscosmos.

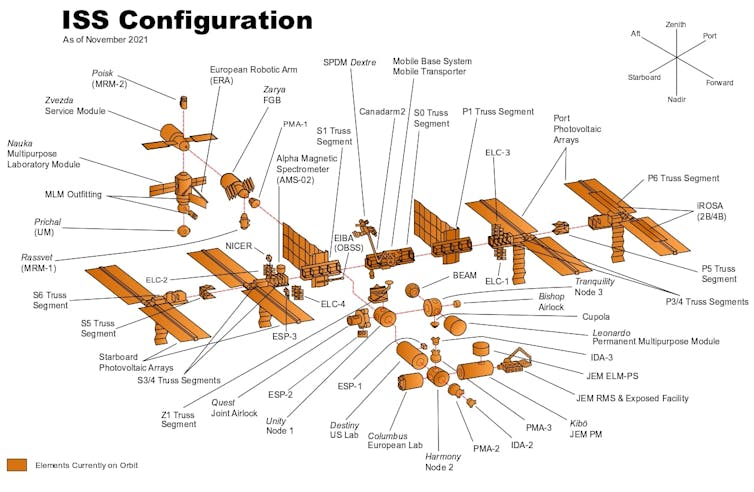

The International Space Station is built of many individual modules that are fully under the control of the countries or agencies that built them.

Territories in space

While the overall operations of the station are run by the Multilateral Coordination Board, things are more complicated when it comes to the modules themselves.

The International Space Station is made of 16 different segments constructed by different countries, including the U.S., Russia, Japan, Italy and the European Space Agency. Under the ISS agreements, each country maintains control over how its modules are used. This includes the Russian Zarya, which provides electricity and propulsion to the station, and Zvezda, which provides all of the station’s life support systems like oxygen production and water recycling.

The result is that ISS modules are treated legally as if they are territorial extensions of their countries of origin. While all crew onboard can theoretically be in and use any of the modules, how they are used must be approved by each country.

While the ISS has functioned under this structure remarkably well since its launch more than 20 years ago, there have been some disputes.

When Russian forces annexed the Ukrainian territory of Crimea in 2014, the U.S. imposed economic sanctions on Russia. As a result, Russian officials announced that they would no longer launch U.S. astronauts to and from the space station beginning in 2020. Since NASA had retired the space shuttle in 2011, the U.S. was entirely dependent on Russian rockets to get astronauts to and from the ISS, and this threat could have meant the end of the American presence aboard the space station entirely.

While Russia did not follow through on its threat and continued to transport U.S. astronauts, the threat needed to be taken seriously. The situation today is quite different. The U.S. has been relying on private SpaceX rockets to transport astronauts to and from the ISS. This makes potential Russian threats to launch access less meaningful.

But the invasion of Ukraine does seem to have upped the intensity of geopolitical maneuvering involving the ISS.

The new U.S. sanctions are designed to “degrade their aerospace industry, including their space program.” The tweet in response from Dmitry Rogozin, the head of Roscosmos, “explained” that Russian modules are key to moving the station when it needs to dodge space junk or adjust its orbit. He went on to say that Russia could either refuse to move the station when needed or even crash it into the U.S., Europe, India or China.

Though dramatic, this is likely an idle threat due to both political consequences and the practical difficulty of getting Russian cosmonauts off the ISS safely. But I am concerned about how the invasion will affect the remaining years of the space station.

In December 2021, the U.S. announced its intention to extend operation of ISS operations from its planned end date of 2024 to 2030. Most ISS partners expressed support for the plan, but Russia will also need to agree to keep the ISS operating beyond 2024. Without Russia’s support, the station – and all of its scientific and cooperative achievements – may face an early end.

The ISS has served as a prime example for how nations can cooperate with one another in an endeavor that has been relatively free from politics. Increasing tensions, threats and more aggressive Russian actions – including its recent test of anti-satellite weapons – are straining the realities of international cooperation in space going forward.

Professor of Strategy and Security Studies, Air University

Disclosure statement

Wendy Whitman Cobb is affiliated with the US Air Force School of Advanced Air and Space Studies. Her views are her own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Defense or any of its components.

NASA shrugs off Roscosmos leader's rant over U.S. sanctions and space station

Director General of Roscosmos Dmitry Rogozin attends a meeting of the State Commission

Article content

NASA on Friday shrugged off public comments from the head of its Russian counterpart suggesting U.S. sanctions imposed against Moscow over the Ukraine crisis could “destroy” U.S.-Russian teamwork on the International Space Station (ISS).

Dmitry Rogozin, director-general of Russian space agency Roscosmos, took to Twitter on Thursday denouncing new constraints on high-tech exports to Russia that U.S. President Joe Biden said were designed to “degrade their aerospace industry, including their space program.”

Advertisemen

Article content

“Do you want to destroy our cooperation on the ISS?” Rogozin asked in a series of tweets, according to a Reuters translation of his remarks. He also noted that orbital control of the space station, through periodic rocket thrusts to maintain a safe altitude, is exercised using engines of a Russian cargo craft docked to the ISS.

“If you block cooperation with us, then who is going to save the ISS from an uncontrolled descent from orbit and then falling onto the territory of the United States or Europe?” he wrote. “There is also a scenario where the 500-ton structure falls on India or China. Do you want to threaten them with this prospect? The ISS doesn’t fly over Russia, so all the risks are yours.”

Rogozin concluded his Twitter rant by urging the U.S. government to “disavow” what he called “Alzheimer’s sanctions.”

Advertisement

Asked for NASA’s response to Rogozin’s outburst, the U.S. space agency said in a statement it was continuing to work with all of its international partners, including Roscosmos, “for the ongoing safe operations of the International Space Station.”

“The new export control measures will continue to allow U.S.-Russia civil space operations,” NASA added. “No changes are planned to the agency’s support for ongoing in-orbit and ground-station operations.”

Apart from Rogozin’s Twitter rhetoric, longstanding U.S.-Russian collaboration aboard the orbiting research platform appeared to otherwise remain on solid footing, even as tensions between the two countries escalated over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Advertisement

Article content

NASA and Roscosmos issued statements this week saying that both agencies were still working toward a “crew exchange” deal under which the former Cold War space rivals would routinely share flights to ISS on each other’s spacecrafts free of cost.

The laboratory outpost, orbiting some 250 miles (400 km) above Earth, is currently home to a crew of four Americans, two Russians and a German astronaut.

NASA said members of Expedition 66, which the current seven-member crew is designated, spent Friday studying how microgravity affects skin cells and plant genetics, as well as how to exercise more effectively in weightlessness. (Reporting by Steve Gorman in Los Angeles; Editing by Sam Holmes)

International Space Station to crash over India? NASA responds to Russian space agency chief’s Twitter tirade

NASA, however, shrugged off Rogozin’s comments that US sanctions on Moscow over Ukraine could “destroy” the two countries’ teamwork on the ISS.

Amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the chief of Moscow’s space programme has warned that sanctions imposed on the country could lead to the International Space Station (ISS) losing orbit and crashing. Roscosmos Director-General Dmitry Rogozin warned that the ongoing sanctions against Russia would lead to the ISS’s premature death. In a tirade on Twitter, Rogozin said the ISS would lose orbit without Russian assistance and eventually fall into the US, Europe, or even India.

Rogozin launched a scathing attack on Thursday, denouncing US President Joe Biden’s decision to restrict high-tech exports to Russia that, he said, were designed to degrade Moscow’s aerospace industry, including the space programme.

Reuters translated Rogozin’s comments, originally posted in Russian.

In a series of questions aimed at the US administration, Rogozin asked if Washington wanted to destroy the cooperation on the ISS. He also pointed out that the space station’s orbital control uses the engines of a Russian cargo craft docked at the space station through periodic rocket thrusts to maintain altitude.

Also Read | Cheetah Action Plan: Indian delegation visits Namibia, big cats to roar in India by mid-2022

In another question aimed at the US, Rogozin asked who would save the ISS from an uncontrolled descent and falling onto US or European territory if it blocked cooperation with Moscow.

He said there was a scenario where the 500-tonne structure would fall on China or India, asking if the US wanted to threaten these countries with that prospect. Rogozin also said the ISS didn’t fly over Russia, so all the risk was for the others to bare.

Rogozin concluded his tirade by urging the US to “disavow” what he described as “Alzheimer’s sanctions”.

NASA, however, shrugged off Rogozin’s comments that US sanctions on Moscow over Ukraine could “destroy” the two countries’ teamwork on the ISS, Reuters reported.

The US space agency said it was continuing to work with all international partners, including Roscosmos, for the safe operations of the ISS.

NASA also added that the export control measures would continue to allow US-Russia civil space operations and there were no changes planned to the agency’s support for in-orbit and ground-station operations.

Despite Rogozin’s Twitter tirade, the longstanding collaboration between the two countries aboard the in-orbit research platform remained on firm footing.

Both NASA and Roscosmos issued statements earlier this week and said the agencies were working toward a ‘crew exchange’ deal under which the former Space Race rivals would share flights to the ISS on each other’s spacecraft for free.

The ISS, orbiting 400 km above Earth, is currently housing two Russians, four Americans, and a German astronaut.

No comments:

Post a Comment