Traces of Yersinia pestis bacteria were found in teeth of people buried at bronze age sites in Cumbria and Somerset

Ian Sample Science editor

THE GUARDIAN

Tue 30 May 2023

The oldest evidence for the plague in Britain has been discovered in 4,000-year-old human remains unearthed at bronze age burial sites in Cumbria and Somerset.

Traces of Yersinia pestis bacteria were found in the teeth of individuals at the Levens Park ring cairn monument near Kendal, and Charterhouse Warren in the Mendips, a site where at least 40 men, women and children were buried, dismembered, in a natural shaft.

The oldest evidence for the plague in Britain has been discovered in 4,000-year-old human remains unearthed at bronze age burial sites in Cumbria and Somerset.

Traces of Yersinia pestis bacteria were found in the teeth of individuals at the Levens Park ring cairn monument near Kendal, and Charterhouse Warren in the Mendips, a site where at least 40 men, women and children were buried, dismembered, in a natural shaft.

The shaft at the Charterhouse Warren site, 1972, where the remains

of at least 40 people were found. Photograph: Tony Audsley

The findings show that an outbreak of the plague which swept Eurasia in the early bronze age spread north-west and across the sea to Britain, thousands of years before the country’s first documented cases of the disease in the Plague of Justinian outbreak in AD541.

“This is the earliest plague found in Britain,” said Pooja Swali, first author on the study in Nature Communications and a PhD student at the Francis Crick Institute in London.

Evidence for the ancient outbreak emerged when Swali and her colleagues screened DNA lurking in the dental pulp of teeth taken from 34 skeletons from the two burial sites. Material from one woman, between 35 and 45 years old, buried at the Cumbrian monument tested positive for plague bacteria, along with two children, aged 10 to 12, at Charterhouse Warren.

The findings show that an outbreak of the plague which swept Eurasia in the early bronze age spread north-west and across the sea to Britain, thousands of years before the country’s first documented cases of the disease in the Plague of Justinian outbreak in AD541.

“This is the earliest plague found in Britain,” said Pooja Swali, first author on the study in Nature Communications and a PhD student at the Francis Crick Institute in London.

Evidence for the ancient outbreak emerged when Swali and her colleagues screened DNA lurking in the dental pulp of teeth taken from 34 skeletons from the two burial sites. Material from one woman, between 35 and 45 years old, buried at the Cumbrian monument tested positive for plague bacteria, along with two children, aged 10 to 12, at Charterhouse Warren.

The burial site at Charterhouse Warren, 1972. Photograph: Tony Audsley

Because DNA degrades rapidly when exposed to the elements, it is possible that other individuals at the burial sites were also infected but were not picked up by the tests. Radiocarbon dating at the sites found that the three people lived at roughly the same time, about 4,000 years ago.

Swali was working in the laboratory late one Friday night when the significance of the findings became clear. “I had my eureka moment, but there was no one to share it with,” she said. “There was a moment of ‘Wow. This is the earliest ever plague genome in Britain’.”

Previous studies have reported cases of the plague across Eurasia between 5,000 and 2,500 years ago, but until the latest work, none had been identified in Britain that long ago.

Because DNA degrades rapidly when exposed to the elements, it is possible that other individuals at the burial sites were also infected but were not picked up by the tests. Radiocarbon dating at the sites found that the three people lived at roughly the same time, about 4,000 years ago.

Swali was working in the laboratory late one Friday night when the significance of the findings became clear. “I had my eureka moment, but there was no one to share it with,” she said. “There was a moment of ‘Wow. This is the earliest ever plague genome in Britain’.”

Previous studies have reported cases of the plague across Eurasia between 5,000 and 2,500 years ago, but until the latest work, none had been identified in Britain that long ago.

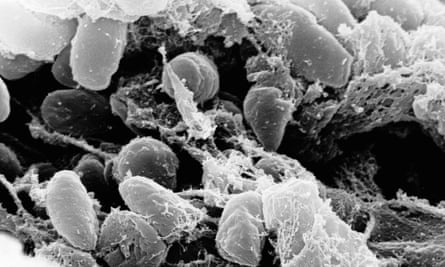

An electron micrograph depicting a mass of Yersinia pestis bacteria.

Photograph: Rocky Mountain Laboratories/AP

DNA analysis showed that all three individuals were infected with a form of Yersinia pestis that lacked the yapC and ymt genes seen in later strains. The ymt gene played an important role in allowing the plague to be spread by fleas, leading to the bubonic form of the disease which triggered devastating pandemics such as the Black Death, which killed half of the European population in the 14th century.

The disease that reached Britain 4,000 years ago was probably the pneumonic form of plague, which causes fever, headache, weakness and pneumonia as the bacteria take hold in the lungs. According to documented cases in Europe, pneumonic plague could spread from a single hunter or herder to an entire community within days.

Prof Rick Schulting, an archaeologist at Oxford University and co-author of the study, said it is unclear what happened at the Charterhouse Warren site, which contains the dismembered bodies of dozens of individuals. “Evidence for violence is very rare in early bronze-age Britain, with nothing on this scale having been discovered before,” he said.

“The finding of plague was completely unexpected, as this disease leaves no traces on the skeleton,” he added. “At the moment we’re not sure how this new evidence fits into the story of what happened at the site, and whether or not there may be some connection between the disease and the violence.”

Dr Pontus Skoglund, another co-author and head of the ancient genomics lab at the Crick, said ancient DNA can help identify and reconstruct outbreaks of infectious disease that would otherwise remain unknown. “The only way we know about this one is through DNA. We would have no idea there was Yersinia pestis around otherwise,” he said.

“We hope to build a record and eventually have a number of examples of outbreaks of infectious disease, epidemics, and pandemics, and then be able to understand more generally how our DNA evolves in response to these and how human societies and health are affected,” he added.

DNA analysis showed that all three individuals were infected with a form of Yersinia pestis that lacked the yapC and ymt genes seen in later strains. The ymt gene played an important role in allowing the plague to be spread by fleas, leading to the bubonic form of the disease which triggered devastating pandemics such as the Black Death, which killed half of the European population in the 14th century.

The disease that reached Britain 4,000 years ago was probably the pneumonic form of plague, which causes fever, headache, weakness and pneumonia as the bacteria take hold in the lungs. According to documented cases in Europe, pneumonic plague could spread from a single hunter or herder to an entire community within days.

Prof Rick Schulting, an archaeologist at Oxford University and co-author of the study, said it is unclear what happened at the Charterhouse Warren site, which contains the dismembered bodies of dozens of individuals. “Evidence for violence is very rare in early bronze-age Britain, with nothing on this scale having been discovered before,” he said.

“The finding of plague was completely unexpected, as this disease leaves no traces on the skeleton,” he added. “At the moment we’re not sure how this new evidence fits into the story of what happened at the site, and whether or not there may be some connection between the disease and the violence.”

Dr Pontus Skoglund, another co-author and head of the ancient genomics lab at the Crick, said ancient DNA can help identify and reconstruct outbreaks of infectious disease that would otherwise remain unknown. “The only way we know about this one is through DNA. We would have no idea there was Yersinia pestis around otherwise,” he said.

“We hope to build a record and eventually have a number of examples of outbreaks of infectious disease, epidemics, and pandemics, and then be able to understand more generally how our DNA evolves in response to these and how human societies and health are affected,” he added.

No comments:

Post a Comment