Bloomberg News | February 26, 2024 |

A nickel briquette. Image from Sherritt International

Many of the world’s biggest nickel mines are facing an increasingly bleak future as they wake up to an existential threat: a near limitless supply of low-cost metal from Indonesia.

With roughly half of all nickel operations unprofitable at recent prices, the bosses of the largest mining companies last week sounded a warning that there was little prospect of a recovery.

The potential collapse of nickel mining from Australia to New Caledonia comes at a time when western governments are scrambling to secure the supply chains needed to decarbonize the global economy. But in an ironic twist, Indonesia’s coal-fired nickel output is pricing out greener metal that’s so far failed to command a market premium.

Wresting control of strategic metals from China has become a focal point of Joe Biden’s administration. Yet while US officials have dashed around the world looking to strike deals for materials such as cobalt and copper, the heaviest reverse has come in Chinese-backed Indonesian nickel, a key component of electric vehicles.

Indonesia now accounts for more than half of world supply, with the potential to reach three-quarters of all production toward the end of the decade.

“There is a serious structural challenge as a result of Indonesian nickel,” said Duncan Wanblad, chief executive officer of Anglo American Plc, after his company took a $500 million writedown on its nickel business last week. “They don’t seem to be letting up anytime soon.”

Traditionally, nickel has been split into two categories: low grade for making stainless steel and high grade for batteries. A huge Indonesian expansion of low-grade production led to a surplus, and, crucially, processing innovations have allowed that glut to be refined into a high-quality product.

Commodity markets have always been susceptible to cyclical volatility, especially when sudden supply and demand imbalances get a push from wider macro upswings or downturns. But what’s happening in nickel right now is different, with the entire industry undergoing a structural shift that has upended forecasts and models.

For BHP Group, the world’s biggest miner, nickel is a rounding error, contributing mostly losses to profits that routinely break $30 billion a year. Yet in recent years the company has championed the metal, seeing it as a key growth market that will help offset its retreat from fossil fuels.

Instead it’s turned into a disaster.

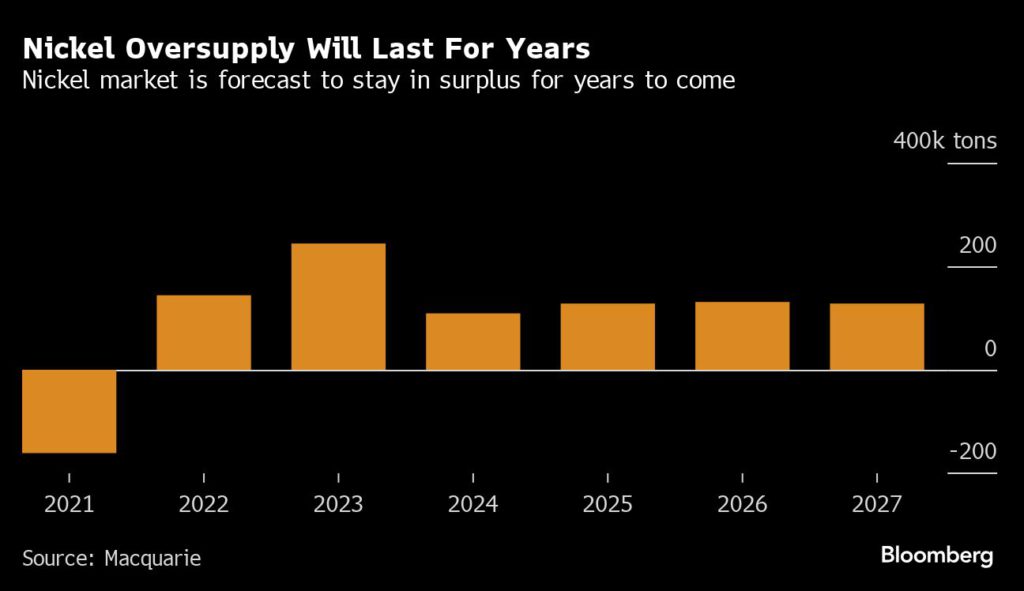

This week CEO Mike Henry conceded that the company will have to make a decision on whether to shutter its flagship nickel business in Australia within the next few months. Having already written down the business’s value by $2.5 billion, Henry said he expects the market to remain in surplus until at least 2030.

That means the pain is likely just starting.

Macquarie Group Ltd. calculates that about 250,000 tons of annual production — equivalent to about 7% of the total — has been taken out of the market by closures, with another 190,000 of planned output delayed.

Combined with economic slowdowns in China and the US and the choppy adoption of EVs, nickel has been pummeled. The price fell 45% last year, and is currently hovering around $17,000 a ton. According to Macquarie, at $18,000 a ton 35% of production is unprofitable, while at $15,000 a ton that jumps to 75%.

Anglo’s CEO Wanblad, who is reviewing nearly all the company’s mines in bid to cut costs, said that he will give the miner’s nickel business time in the face of the Indonesian threat.

“Our nickel business will undergo a fulsome review in terms of holding its head above water and making a viable profit,” he said. “I’m not giving up on the guys to come up with a plan that might help them readjust themselves into a position where they can function effectively.”

Glencore Plc, which has already moved to shutter its nickel operations on the islands of New Caledonia, is one of the world’s biggest producers with sprawling businesses in Canada and Australia. At current prices, that business will make just $500 million this year, with CEO Gary Nagle expecting prices to remain depressed.

“We see continuing strong production growth out of Indonesia,” Nagle said. “We do not expect significant price recovery in the short to medium term.”

With more than half a decade of oversupply ahead, more mines are likely to close before things get better. Should the market finally rebalance, that will leave Indonesia and China with even more market share then they already have.

Still, Indonesia’s rapid expansion has drawn criticism. Much of its production comes from coal-powered energy, giving it higher emissions per ton than rival producers, and its rapid expansion is eroding rainforests.

With little prospect of a near term recovery, western miners are pinning their hopes on state aid in the short term and a push toward customers — such as carmakers — demanding “greener” nickel in the future and being willing to pay more for it.

BHP this week called for the London Metal Exchange to expand its responsible sourcing policy to include environmental due diligence, helping to differentiate production from Indonesian and Chinese supply.

Still, as conceded by Glencore, so far buyers of nickel are unwilling to pay more.

“Right now there is not much of a premium in the market,” Nagle said.

(By Thomas Biesheuvel)

Fortescue’s Forrest urges LME to separate ‘clean’ nickel contracts

Reuters | February 26, 2024

Andrew Forrest. (Image by Mines and Money, Flickr).

The London Metal Exchange (LME) should classify its nickel contracts into “clean” and “dirty” ones to give customers more choice, Australian iron ore magnate Andrew Forrest said on Monday.

The comment by Forrest, chairman and founder of Fortescue Metals Group, is part of a push by miners and Australian lawmakers to save the country’s nickel industry after prices collapsed amid a jump in cheaper supplies from Indonesia.

Nickel, a key ingredient in electric vehicle batteries, is typically produced to higher environmental and regulatory standards in Australia than in Indonesia. That has Australian producers calling for a green premium.

“If you’ve got dirty nickel in your battery systems, then you want to know about that because you don’t want to propagate that and you want the choice to buy clean nickel if you can. So the London Metal Exchange must differentiate between clean and dirty,” Forrest told Australia’s national press club.

In an emailed response to Reuters, an LME spokesperson said the exchange “drives and supports the metals and mining industry on several sustainability measures to ensure transparency throughout the supply chain to consumers”.

The LME, the world’s biggest market for industrial metals, has linked up with German online platform Metalshub, which in 2022 developed a price index for class 1 nickel briquette premiums. Briquettes are solid forms of nickel obtained by compressing the metal’s powder or flakes.

“Low-carbon nickel can already be listed on Metalshub today and the transaction data supports identification of a credible ‘green premium’ to the LME price,” the spokesperson added.

Australia’s nickel industry is shedding hundreds of jobs. Forrest’s private investment arm Wyloo Metals said last month it would put its Western Australian nickel operations on care and maintenance at the end of May due to low prices. It bought those assets last year for $504 million.

(By Melanie Burton; Editing by Edwina Gibbs and Jan Harvey)

Reuters | February 26, 2024

Andrew Forrest. (Image by Mines and Money, Flickr).

The London Metal Exchange (LME) should classify its nickel contracts into “clean” and “dirty” ones to give customers more choice, Australian iron ore magnate Andrew Forrest said on Monday.

The comment by Forrest, chairman and founder of Fortescue Metals Group, is part of a push by miners and Australian lawmakers to save the country’s nickel industry after prices collapsed amid a jump in cheaper supplies from Indonesia.

Nickel, a key ingredient in electric vehicle batteries, is typically produced to higher environmental and regulatory standards in Australia than in Indonesia. That has Australian producers calling for a green premium.

“If you’ve got dirty nickel in your battery systems, then you want to know about that because you don’t want to propagate that and you want the choice to buy clean nickel if you can. So the London Metal Exchange must differentiate between clean and dirty,” Forrest told Australia’s national press club.

In an emailed response to Reuters, an LME spokesperson said the exchange “drives and supports the metals and mining industry on several sustainability measures to ensure transparency throughout the supply chain to consumers”.

The LME, the world’s biggest market for industrial metals, has linked up with German online platform Metalshub, which in 2022 developed a price index for class 1 nickel briquette premiums. Briquettes are solid forms of nickel obtained by compressing the metal’s powder or flakes.

“Low-carbon nickel can already be listed on Metalshub today and the transaction data supports identification of a credible ‘green premium’ to the LME price,” the spokesperson added.

Australia’s nickel industry is shedding hundreds of jobs. Forrest’s private investment arm Wyloo Metals said last month it would put its Western Australian nickel operations on care and maintenance at the end of May due to low prices. It bought those assets last year for $504 million.

(By Melanie Burton; Editing by Edwina Gibbs and Jan Harvey)

No comments:

Post a Comment