Pilots flying by the volcano reported seeing "Pele's hair."

Kilauea volcano is erupting, sending lava and thread-like pieces of volcanic glass, known as Pele's hair, into Hawaii's skies, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and the National Weather Service.

The eruption began at about 3:20 p.m. local Hawaii time Wednesday (Sept. 29), when the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory detected a glow from its webcam at Kilauea summit. That glow indicated a lava eruption happening at Halema'uma'u crater — a pit crater nestled in the much larger Kilauea caldera, or crater.

The webcam footage also revealed fissures at the base of Halema'uma'u crater that were releasing lava flows onto the surface of the lava lake that had been active until May 2021, the USGS said in a statement. However, the eruption at Kilauea — located within Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, on Hawaii's Big Island — is confined to Halema'uma'u crater, meaning it's not currently a threat to the public.

Related: Photos: Fiery lava from Kilauea volcano erupts on Hawaii's Big Island

"At this time, we don't believe anybody or any residents are in danger, but we do want to remind folks the park remains open," Cyrus Johnasen, a Hawaii County spokesperson, told Hawaii news station KHON2 on Sept. 29. "It will remain open until the evening. Please proceed with caution," especially for those with respiratory conditions, he added.

However, the part of the park where the eruption is happening is currently closed to the public, according to the USGS.

Due to the eruption, the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory has elevated Kilauea's volcano alert level from "watch" to "warning" and its aviation color code from orange to red, which warns pilots about possible ash emissions. Those are the highest warning levels, meaning a "major volcanic eruption is imminent, underway or suspected, with hazardous activity both on the ground and in the air," according to the USGS.

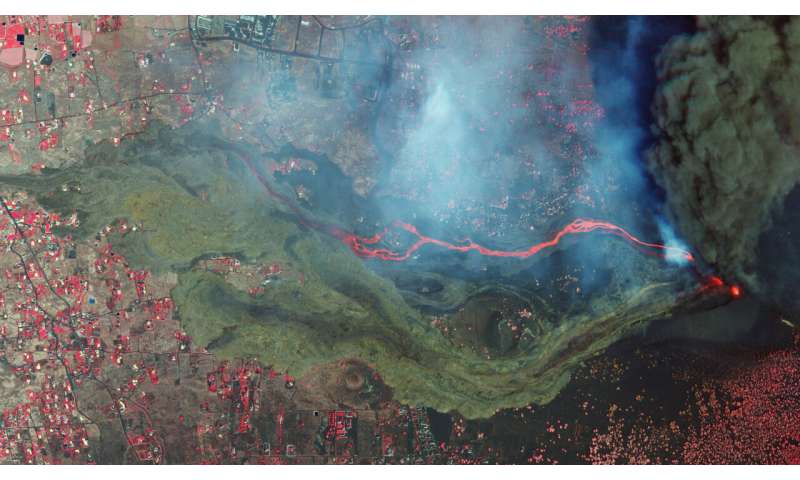

The eruption within Halema'uma'u crater is spewing low lava fountains in the center of the lava lake (pictured) and along the western wall of Halema'uma'u. (Image credit: M. Patrick/USGS

Meanwhile, several pilots flying aircraft near Kilauea Wednesday evening reported seeing volcanic glass known as Pele's hair, according to the National Weather Service. The golden, sharp strands of glass — named for Pele, the Hawaiian goddess of fire and volcanoes — form when gas bubbles within lava burst at the surface.

"The skin of the bursting bubbles flies out, and some of the skin becomes stretched into these very long threads, sometime[s] as long as a couple of feet [more than half a meter] or so," Don Swanson, a research geologist at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, previously told Live Science.

Pele's hair can be beautiful, but it poses a danger if it's ingested through drinking water, Swanson cautioned.

The current eruption is the latest of a long string of volcanic activity at Kilauea. At an elevation of 4,009 feet (1,222 m) aboveground, the shield-shaped volcano has a magma-pumping system that extends more than 37 miles (60 kilometers) below Earth, according to the USGS. Kilauea has erupted 34 times since 1952, and it erupted almost continuously from 1983 to 2018 along its East Rift Zone. A vent at Halema'uma'u crater was home to an active lava pond and a vigorous gas plume from 2008 to 2018.

Kilauea's volcanic activity also made headlines in May 2018, when the lava lake at the summit caldera drained just as the Eastern Rift Zone revved to life with lava fountains and new fissures, whose lava created a red-hot river that destroyed hundreds of houses before draining into the ocean.

From December 2020 to May 2021, a summit eruption made a lava lake within Halema'uma'u crater, and in August 2021, a series of small earthquakes rattled the summit.

President Nayib Bukele has tweeted that El Salvador has begun mining Bitcoin using geothermal power from volcanoes.

By Scott Chipolina

Oct 1, 2021

EL SALVADOR PLANS TO USE GEOTHERMAL ENERGY FROM VOLCANOES TO MINE BITCOIN. IMAGE: SHUTTERSTOCK

The President of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, took to Twitter early this morning to provide an update on the country’s recently launched Bitcoin mining industry.

According to Bukele's tweet, El Salvador has mined almost $500 worth of Bitcoin, a number that the government surely intends to increase over time.

In a follow-up tweet, Bukele clarified that “this is officially the first #Bitcoin mining from the #volcanode,” the country’s volcano-powered Bitcoin mine. Earlier this week, he shared a video on Twitter that appeared to show the country taking its first steps to mining Bitcoin using geothermal energy from volcanoes.

The video—which shows a data center in a forest before zooming in on a worker wiring up a Bitcoin mining machine—has been viewed over 2 million times already. In today’s tweet, Bukele noted that the project is “still testing and installing.”

Bitcoin mining is controversial given its energy-consumption demands and resulting carbon footprint. Due to increased scrutiny over the cryptocurrency’s impact on the environment, some miners have turned to cleaner, renewable power sources, such as geothermal energy.

In June, President Bukele said that El Salvador’s state-owned electricity company LaGeo would use “very cheap, 100% clean, 100% renewable, 0 emissions energy from our volcanoes,” to mine Bitcoin.

While the decision may have spared President Bukele criticism from environmentalists, his own population remains divided over the country’s embrace of Bitcoin as legal tender.

Bukele's Bitcoin ambitions

President Bukele first announced his plans to accept Bitcoin as legal tender in El Salvador during this year’s Bitcoin Conference in Miami.

Ever since, his decision has been mired in controversy, with some Salvadorans claiming that the Bitcoin Law has exposed President Bukele’s already well-documented authoritarian streak.

Despite President Bukele’s suggestions to the contrary, Article 7 of the Bitcoin Law compels businesses to accept Bitcoin as a payment, even if they don’t want to. And the government has doubled down on this stance ever since.

“The government has harassed big business and small business alike. They’ve sent government agents to inspect businesses to ensure they are following labor regulations just because C-level executives have said negative things about the Bitcoin Law,” one local businessperson told Decrypt on condition of anonymity.

Critics who've spoken out against the government’s policy have also been targeted. “The police doesn’t have to take anyone to court. They just scare one of the vocal dissidents with kidnapping him a couple of hours or a couple of days,” another local businessperson told Decrypt, referring to the illegal arrest of Bitcoin critic Mario Gomez earlier this month.

This summer also saw multiple surveys and protest after protest after protest—all evidencing the fact that many Salvadorans do not wish to accept Bitcoin as legal tender.

Yet, President Bukele’s embrace of Bitcoin has continued—with crucial details of the project yet to be revealed.

“There are so many things that are not being disclosed. For example, who’s holding the private keys to these Bitcoin?" Nolvia Serrano, head of operations at crypto wallet provider BlockBank, asked on the Decrypt Daily podcast earlier this week. "Also, what’s the criteria for saying, 'Oh, today, we’re going to buy more Bitcoin, or we’re going to wait until next month.' We don’t know that."

“There’s no space to make wrong calls on this, and we need to be transparent because the cryptocurrency community cares about these principles,” she added.

However, many of the world’s loudest Bitcoin advocates, including Jack Mallers, Michael Saylor and Peter McCormack—have rushed to heap praise on the crypto ambitions of the self-professed “coolest dictator in the world.”

Lava flows from a volcano on the Canary island of La Palma, Spain on Monday Sept. 27, 2021. A Spanish island volcano that has buried more than 500 buildings and displaced over 6,000 people since last week lessened its activity on Monday, although scientists warned that it was too early to declare the eruption phase finished and authorities ordered residents to stay indoors to avoid the unhealthy fumes from lava meeting sea waters. Credit: AP Photo/Daniel Roca

Lava flows from a volcano on the Canary island of La Palma, Spain on Monday Sept. 27, 2021. A Spanish island volcano that has buried more than 500 buildings and displaced over 6,000 people since last week lessened its activity on Monday, although scientists warned that it was too early to declare the eruption phase finished and authorities ordered residents to stay indoors to avoid the unhealthy fumes from lava meeting sea waters. Credit: AP Photo/Daniel Roca