One of Hurricane Katrina’s Most Important Lessons Isn’t About Storm Preparations – It’s About Injustice

National Archives via Mapping Inequality/University of Richmond

Twenty years after Hurricane Katrina swept through New Orleans, the images still haunt us: entire neighborhoods underwater, families stranded on rooftops and a city brought to its knees.

We study disaster planning at Texas A&M University and look for ways communities can improve storm safety for everyone, particularly low-income and minority neighborhoods.

Katrina made clear what many disaster researchers have long found: Hazards such as hurricanes may be natural, but the death and destruction is largely human-made.

How New Orleans built inequality into its foundation

New Orleans was born unequal. As the city grew as a trade hub in the 1700s, wealthy residents claimed the best real estate, often on higher ground formed by river sediment. The city had little high ground, so everyone else was left in “back-of-town” areas, closer to swamps where land was cheap and flooding common.

In the early 1900s, new pumping technology enabled development in flood-prone swamplands and housing spread, but the pumping caused land subsidence that made flooding worse in neighborhoods such as Lakeview, Gentilly and Broadmoor.

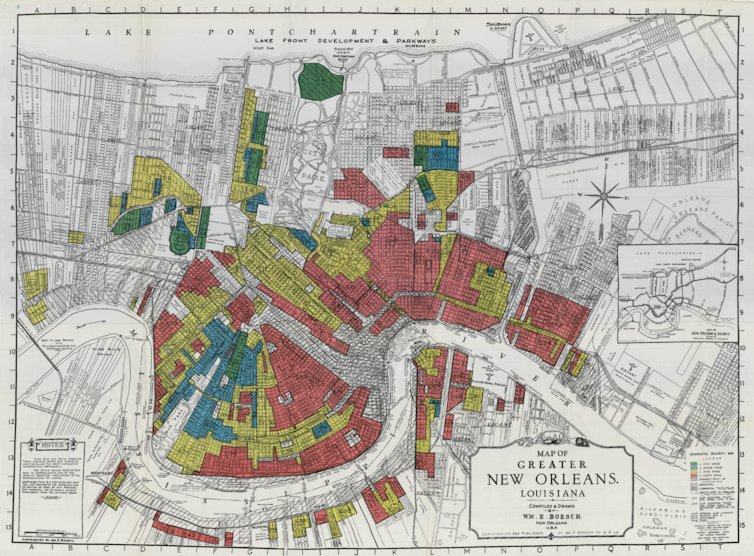

Then redlining started in the 1930s. To guide federal loan decisions, government agencies began using maps that rated neighborhoods by financial risk. Predominantly Black neighborhoods were typically marked as “high risk,” regardless of the actual housing quality.

This created a vicious cycle: Black and low-income families were already stuck in flood-prone areas because that’s where cheap land was. Redlining kept their property values lower. Black Americans were also denied government-backed mortgages and GI Bill benefits that could have helped them move to safer neighborhoods on higher ground.

Hurricane Katrina showed how those lines translate to vulnerability.

When history came calling

On Aug. 29, 2005, as Hurricane Katrina battered New Orleans, the levees protecting the city broke and water flooded about 80% of the city. The damage followed racial geography − the spatial patterns of where Black and white residents lived due to decades of segregation − like a blueprint.

About three-quarters of Black residents experienced serious flooding, compared with half of white residents.

Between 100,000 and 150,000 people couldn’t evacuate. They were disproportionately people who were elderly, Black, poor and without cars. Among survivors who did not evacuate, 55% did not have a car or another way to get out, and 93% were Black. More than 1,800 people lost their lives.

This lack of transportation — what scholars call “transportation poverty” — left people stranded in the city’s bowl-shaped geography, unable to escape when the levees failed.

Recovery that made things worse

After Hurricane Katrina, the federal government created the Road Home program to help homeowners rebuild. But the program had a devastating design flaw: It calculated aid based on prehurricane home value or repair costs, whichever was less.

That meant low-income homeowners, who already lived in areas with lower property values due to the history of discrimination, received less money. A family whose US$50,000 home needed $80,000 in repairs would receive only $50,000, while a family whose $200,000 home needed the same $80,000 in repairs would receive the full repair amount. The average gap between damage estimates and rebuilding funds was $36,000.

As a result, people in poor and Black neighborhoods had to cover about 30% of rebuilding costs after all aid, while those in wealthy areas faced only about 20%. Families in the poorest areas had to pay thousands of dollars out-of-pocket to complete repairs, even after government help and insurance, and that slowed the recovery process.

This pattern isn’t unique to New Orleans. A study examining data from Hurricane Andrew in Miami (1992) and Hurricane Ike in Galveston (2008) found that housing recovery was consistently slow and unequal in low-income and minority neighborhoods. Lower-income families are less likely to have adequate insurance or savings for quick rebuilding. Low-value homes with extensive damage still had not regained their prestorm value four years later, while higher-value homes sustaining even moderate damage gained value.

Ten years after Katrina, while 70% of white residents felt New Orleans had recovered, only 44% of Black residents could look around their neighborhood and say the same.

Community-led solutions for climate resilience

Katrina’s lessons in the inequality of disasters are important for communities today as climate change brings more extreme weather.

Federal Emergency Management Agency denial rates for disaster aid remain high due to bureaucratic obstacles such as complex application processes that bounce survivors among multiple agencies, often resulting in denials and delays of critical funds. These are the same systemic barriers that added to the reasons Black communities recovered more slowly after Hurricane Katrina. FEMA’s own advisory council reported that institutional assistance policies tend to enrich wealthier, predominantly white areas, while underserving low-income and minority communities throughout all stages of disaster response.

The lessons from New Orleans also point to ways communities can build disaster resilience across the entire population. In particular, as cities plan protective measures — elevating homes, buyout programs and flood-proofing assistance — Hurricane Katrina showed the need to pay attention to social vulnerabilities and focus aid where people need the most assistance.

The choice America faces

In our view, one of Katrina’s most important lessons is about social injustice. The disproportionate suffering in Black communities wasn’t a natural disaster but a predictable result of policies concentrating risk in marginalized neighborhoods.

In many American cities, policies still leave some communities facing a greater risk of disaster damage. To protect residents, cities can start by investing in vulnerable areas, empowering a community-led recovery and ensuring race, income or ZIP code never again determine who receives help with the recovery.

Natural disasters don’t have to become human catastrophes. Confronting the policies and other factors that leave some groups at greater risk can avoid a repeat of the devastation the world saw in Katrina.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.