IMPERIALISM HIGHEST STAGE OF CAPITALI$M

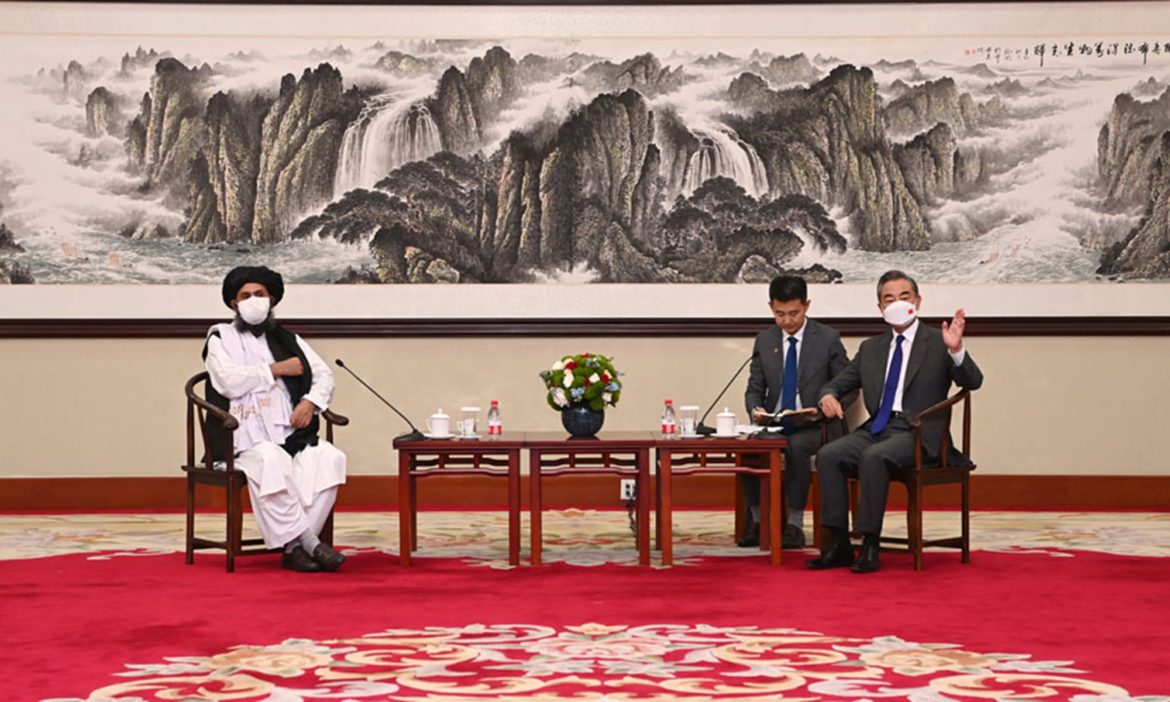

China will be our main partner, say TalibanBeijing ready to invest in Afghanistan, help rebuild country, says Taliban spokesman

Attribution: China's Foreign Ministry

02/09/2021

ROME (AA) – China will be the Taliban’s “main partner” and help rebuild Afghanistan, according to a spokesman for the group.

“China will be our main partner and represents a great opportunity for us because it is ready to invest in our country and support reconstruction efforts,” Zabihullah Mujahid said in an interview published by Italian newspaper La Repubblica on Wednesday.

He said the Taliban value China’s Belt and Road Initiative as the project will revive the ancient Silk Road.

He said China will also help Afghanistan fully utilize its rich copper resources and give the country a path into global markets.

The Taliban also view Russia as an important partner in the region and will maintain good relations with Moscow, he added.

Speaking about the Kabul airport, Mujahid said the facility is fully under Taliban control but has been seriously damaged.

Qatar and Turkey are leading efforts to resume operations at the airport, he told the Italian publication.

“The airport should be clean within the next three days and will be rebuilt in a short time. I hope it will be operational again in September,” he said.

On relations with Italy, Mujahid said the Taliban hope Italy will recognize their government and reopen its embassy in Kabul.

The Taliban took control of Afghanistan on Aug. 15, forcing President Ashraf Ghani and other top officials to flee the country.

The group has been working to form a government and an announcement is expected on Friday.

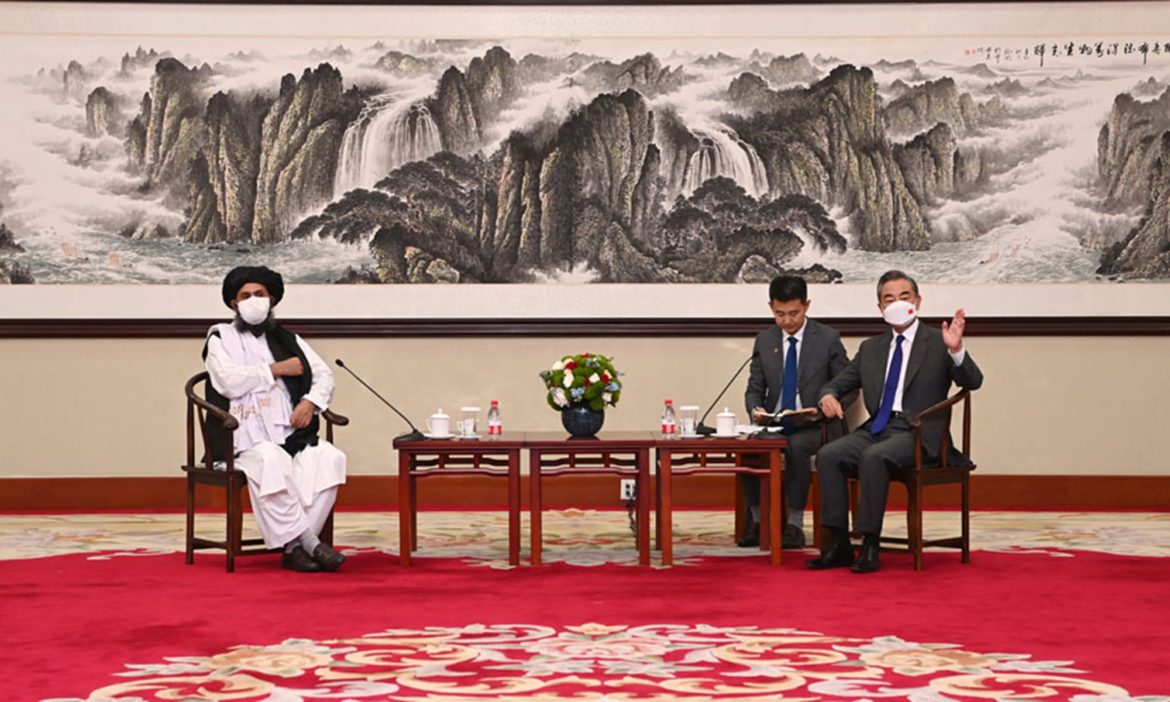

Attribution: China's Foreign Ministry

02/09/2021

ROME (AA) – China will be the Taliban’s “main partner” and help rebuild Afghanistan, according to a spokesman for the group.

“China will be our main partner and represents a great opportunity for us because it is ready to invest in our country and support reconstruction efforts,” Zabihullah Mujahid said in an interview published by Italian newspaper La Repubblica on Wednesday.

He said the Taliban value China’s Belt and Road Initiative as the project will revive the ancient Silk Road.

He said China will also help Afghanistan fully utilize its rich copper resources and give the country a path into global markets.

The Taliban also view Russia as an important partner in the region and will maintain good relations with Moscow, he added.

Speaking about the Kabul airport, Mujahid said the facility is fully under Taliban control but has been seriously damaged.

Qatar and Turkey are leading efforts to resume operations at the airport, he told the Italian publication.

“The airport should be clean within the next three days and will be rebuilt in a short time. I hope it will be operational again in September,” he said.

On relations with Italy, Mujahid said the Taliban hope Italy will recognize their government and reopen its embassy in Kabul.

The Taliban took control of Afghanistan on Aug. 15, forcing President Ashraf Ghani and other top officials to flee the country.

The group has been working to form a government and an announcement is expected on Friday.

Chinese Firms Don’t Want to Pay Afghanistan’s Costs

FOREIGN AFFAIRS

August 29, 2021

Despite Beijing’s huge war chest of yuan and a tested comfort for dealing with dictators, the United States has little to fear in a Chinese foray to turn its western neighbor into a client state. Far more likely, Beijing would suffer the same fate as many other empires that tried to shape Afghanistan in its own image. The economic, political, and strategic contexts all work against Beijing.

The United States is paying a heavy cost for the messy way in which it is withdrawing from Afghanistan, but an equally serious concern for many analysts has been the long-term prospects of China filling the vacuum left by the United States and expanding its geopolitical influence farther into the Eurasian landmass. When viewed through the lens of the growing rivalry between Washington and Beijing, it’s not hard to imagine seeing Afghanistan now being painted red and falling into China’s camp.

The United States is paying a heavy cost for the messy way in which it is withdrawing from Afghanistan, but an equally serious concern for many analysts has been the long-term prospects of China filling the vacuum left by the United States and expanding its geopolitical influence farther into the Eurasian landmass. When viewed through the lens of the growing rivalry between Washington and Beijing, it’s not hard to imagine seeing Afghanistan now being painted red and falling into China’s camp.

Despite Beijing’s huge war chest of yuan and a tested comfort for dealing with dictators, the United States has little to fear in a Chinese foray to turn its western neighbor into a client state. Far more likely, Beijing would suffer the same fate as many other empires that tried to shape Afghanistan in its own image. The economic, political, and strategic contexts all work against Beijing.

Whatever normal economy existed has all but been decimated after four decades of war. According to the World Bank, Afghanistan’s total economy in 2020 was valued at only $19.8 billion, making it smaller than every single Fortune 500 company. For a country of 39.9 million people, that translates into a meager per capita income of only $509—or barely above subsistence.

There was great fanfare a decade ago when U.S. officials estimated Afghanistan had a $1 trillion treasure trove of minerals, including the ever-hyped lithium and rare earths. Some have tripled that estimate. That is likely just hype, but even if true on paper, Afghanistan lacks the infrastructure, political stability, and skilled labor to effectively exploit these resources—as was amply shown during the U.S. era. There are many other locales with the same resources but far better conditions for foreign investors.

With few productive assets, the country’s economy was already deeply dependent on the United States’ provision of dollars for conducting international transactions and foreign aid for many basic necessities. In the wake of the Taliban victory, the United States, Great Britain, and the International Monetary Fund have frozen much of the government’s reserves and accounts. Consumer fears have reportedly driven inflation to more than 50 percent. Perhaps most importantly, despite the current bottleneck and bombings at Kabul’s airport, the mass exodus of Afghanistan’s best and brightest individuals—whether during the U.S. evacuation or fleeing the country through other means—will further deplete the country of critical talent needed for sustainable development and good governance.

China’s economic opportunities are thus quite meager. Afghanistan’s total external trade in 2020 was a paltry $7.83 billion and two-way foreign direct investment a mere $50 million, barely a rounding error for most of its neighbors, let alone China.

Nor has Beijing particularly laid the groundwork for an expanded presence. Despite some reports, China is a minor player in Afghanistan’s economy. It ranks no better than the country’s sixth largest trading partner, trailing Pakistan, India, the United Arab Emirates, Iran, and the United States, according to the data supplied by its partners to the IMF. According to the U.N. Comtrade Database, China’s top exports to Afghanistan would have been impressive—in the 1960s: tires, basic telecom equipment, motorcycles, mopeds, and fabrics. (The United States’ exports are no less odd, as they were almost all war-related: special-purpose vehicles, fighter aircraft, military aircraft parts, telecom equipment, and tanks.)

Equally telling, although Afghanistan signed up for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, according to the Council on Foreign Relations, there only two BRI projects totaling $3.4 billion; by contrast, China has poured at least $87 billion into 122 BRI projects in neighboring Pakistan.

Afghanistan is one of the least wired countries in the world. With only 11.5 percent of Afghans online, by World Bank data, and a decrepit road system, Alibaba, Tencent, or any other Chinese retailer would have a hard time making an afghani there. And given the limited infrastructure and security risks, the notion that Chinese mining ventures in search of lithium will be the first through the door as the U.S. departs—and make a real run of it—is fanciful.

The obstacles presented by Afghanistan’s sheer poverty are rivaled by the political challenges China would have to overcome to bring the country under its thumb. China has had success in several authoritarian countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia, but it is most comfortable interacting with centralized regimes where economic growth, even via corruption, is prized and resources are easy to procure.

Afghanistan is the exact opposite: a highly fragmented political system now overseen by a deeply conservative theocracy in many ways opposed to the basic elements of modernization. Beijing is used to dealing with corruption, but it’s not just a case of bribery but who to bribe effectively. The depth of local knowledge and number of interlocuters needed to get projects in Afghanistan moving would create astronomical costs. In such an environment, it is hard to see how Chinese investments would generate extensive new economic activity that yields new customers or makes the country highly dependent on Beijing.

To make matters worse, China’s most innovative private firms, who would be best positioned to come up with novel solutions in Afghanistan, are currently being eviscerated and scared silly by an aggressive campaign to trim their sails and bring their executives to heel. Given the risks, fewer firms than usual will be willing to venture abroad. That leaves the more obedient but less agile and old-fashioned state-owned enterprises to do Beijing’s bidding. They certainly can build highways—but quite often to nowhere. And even they may not want to handle the blowback that would come from possible terror attacks on their staff, especially from an increasingly Islamophobic Chinese public; scattered incidents in Pakistan have already caused disquiet in China.

The icing on this bitter cake is the stormy geostrategic context. Like dictator Kim Jong Un’s North Korea, the Taliban will be international pariahs deprived of easy access to the global banking system and international markets. Given the likelihood of being slapped with Western sanctions, the chance of multinationals from China or elsewhere wanting to insert a landlocked Afghanistan into their global supply chains is amazingly small. On top of that, an assertive China would very well draw negative attention—and countermoves—from surrounding larger powers, including Pakistan, India, Iran, and Russia. There may be no tougher neighborhood in which to do business.

For all of those reasons, if China attempts to fill the vacuum, its investors and businesses there would be rapidly starved of commercial oxygen and come racing back across the border, humbled by their experience.

However, where the British, Russians, and Americans have failed, perhaps Beijing will have the magic touch. If by some miracle China manages to turn things around, laying down infrastructure that is then effectively utilized by producers and consumers—all overseen by a restored civil service—this might provide the country a thin foundation of stability. That wouldn’t be a catastrophe for Washington. A developing Afghanistan, even if on Beijing’s dime and under its influence, would likely be far less of a haven for terrorism toward anyone than a country beset by endemic poverty.

Regardless of what Beijing does—whether it gets bogged down (the most likely outcome) or somehow pulls a rabbit out of a hat—Washington would benefit either way. Chinese President Xi Jinping, it’s your turn.

August 29, 2021

Despite Beijing’s huge war chest of yuan and a tested comfort for dealing with dictators, the United States has little to fear in a Chinese foray to turn its western neighbor into a client state. Far more likely, Beijing would suffer the same fate as many other empires that tried to shape Afghanistan in its own image. The economic, political, and strategic contexts all work against Beijing.

The United States is paying a heavy cost for the messy way in which it is withdrawing from Afghanistan, but an equally serious concern for many analysts has been the long-term prospects of China filling the vacuum left by the United States and expanding its geopolitical influence farther into the Eurasian landmass. When viewed through the lens of the growing rivalry between Washington and Beijing, it’s not hard to imagine seeing Afghanistan now being painted red and falling into China’s camp.

The United States is paying a heavy cost for the messy way in which it is withdrawing from Afghanistan, but an equally serious concern for many analysts has been the long-term prospects of China filling the vacuum left by the United States and expanding its geopolitical influence farther into the Eurasian landmass. When viewed through the lens of the growing rivalry between Washington and Beijing, it’s not hard to imagine seeing Afghanistan now being painted red and falling into China’s camp.

Despite Beijing’s huge war chest of yuan and a tested comfort for dealing with dictators, the United States has little to fear in a Chinese foray to turn its western neighbor into a client state. Far more likely, Beijing would suffer the same fate as many other empires that tried to shape Afghanistan in its own image. The economic, political, and strategic contexts all work against Beijing.

Whatever normal economy existed has all but been decimated after four decades of war. According to the World Bank, Afghanistan’s total economy in 2020 was valued at only $19.8 billion, making it smaller than every single Fortune 500 company. For a country of 39.9 million people, that translates into a meager per capita income of only $509—or barely above subsistence.

There was great fanfare a decade ago when U.S. officials estimated Afghanistan had a $1 trillion treasure trove of minerals, including the ever-hyped lithium and rare earths. Some have tripled that estimate. That is likely just hype, but even if true on paper, Afghanistan lacks the infrastructure, political stability, and skilled labor to effectively exploit these resources—as was amply shown during the U.S. era. There are many other locales with the same resources but far better conditions for foreign investors.

With few productive assets, the country’s economy was already deeply dependent on the United States’ provision of dollars for conducting international transactions and foreign aid for many basic necessities. In the wake of the Taliban victory, the United States, Great Britain, and the International Monetary Fund have frozen much of the government’s reserves and accounts. Consumer fears have reportedly driven inflation to more than 50 percent. Perhaps most importantly, despite the current bottleneck and bombings at Kabul’s airport, the mass exodus of Afghanistan’s best and brightest individuals—whether during the U.S. evacuation or fleeing the country through other means—will further deplete the country of critical talent needed for sustainable development and good governance.

China’s economic opportunities are thus quite meager. Afghanistan’s total external trade in 2020 was a paltry $7.83 billion and two-way foreign direct investment a mere $50 million, barely a rounding error for most of its neighbors, let alone China.

Nor has Beijing particularly laid the groundwork for an expanded presence. Despite some reports, China is a minor player in Afghanistan’s economy. It ranks no better than the country’s sixth largest trading partner, trailing Pakistan, India, the United Arab Emirates, Iran, and the United States, according to the data supplied by its partners to the IMF. According to the U.N. Comtrade Database, China’s top exports to Afghanistan would have been impressive—in the 1960s: tires, basic telecom equipment, motorcycles, mopeds, and fabrics. (The United States’ exports are no less odd, as they were almost all war-related: special-purpose vehicles, fighter aircraft, military aircraft parts, telecom equipment, and tanks.)

Equally telling, although Afghanistan signed up for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, according to the Council on Foreign Relations, there only two BRI projects totaling $3.4 billion; by contrast, China has poured at least $87 billion into 122 BRI projects in neighboring Pakistan.

Afghanistan is one of the least wired countries in the world. With only 11.5 percent of Afghans online, by World Bank data, and a decrepit road system, Alibaba, Tencent, or any other Chinese retailer would have a hard time making an afghani there. And given the limited infrastructure and security risks, the notion that Chinese mining ventures in search of lithium will be the first through the door as the U.S. departs—and make a real run of it—is fanciful.

The obstacles presented by Afghanistan’s sheer poverty are rivaled by the political challenges China would have to overcome to bring the country under its thumb. China has had success in several authoritarian countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia, but it is most comfortable interacting with centralized regimes where economic growth, even via corruption, is prized and resources are easy to procure.

Afghanistan is the exact opposite: a highly fragmented political system now overseen by a deeply conservative theocracy in many ways opposed to the basic elements of modernization. Beijing is used to dealing with corruption, but it’s not just a case of bribery but who to bribe effectively. The depth of local knowledge and number of interlocuters needed to get projects in Afghanistan moving would create astronomical costs. In such an environment, it is hard to see how Chinese investments would generate extensive new economic activity that yields new customers or makes the country highly dependent on Beijing.

To make matters worse, China’s most innovative private firms, who would be best positioned to come up with novel solutions in Afghanistan, are currently being eviscerated and scared silly by an aggressive campaign to trim their sails and bring their executives to heel. Given the risks, fewer firms than usual will be willing to venture abroad. That leaves the more obedient but less agile and old-fashioned state-owned enterprises to do Beijing’s bidding. They certainly can build highways—but quite often to nowhere. And even they may not want to handle the blowback that would come from possible terror attacks on their staff, especially from an increasingly Islamophobic Chinese public; scattered incidents in Pakistan have already caused disquiet in China.

The icing on this bitter cake is the stormy geostrategic context. Like dictator Kim Jong Un’s North Korea, the Taliban will be international pariahs deprived of easy access to the global banking system and international markets. Given the likelihood of being slapped with Western sanctions, the chance of multinationals from China or elsewhere wanting to insert a landlocked Afghanistan into their global supply chains is amazingly small. On top of that, an assertive China would very well draw negative attention—and countermoves—from surrounding larger powers, including Pakistan, India, Iran, and Russia. There may be no tougher neighborhood in which to do business.

For all of those reasons, if China attempts to fill the vacuum, its investors and businesses there would be rapidly starved of commercial oxygen and come racing back across the border, humbled by their experience.

However, where the British, Russians, and Americans have failed, perhaps Beijing will have the magic touch. If by some miracle China manages to turn things around, laying down infrastructure that is then effectively utilized by producers and consumers—all overseen by a restored civil service—this might provide the country a thin foundation of stability. That wouldn’t be a catastrophe for Washington. A developing Afghanistan, even if on Beijing’s dime and under its influence, would likely be far less of a haven for terrorism toward anyone than a country beset by endemic poverty.

Regardless of what Beijing does—whether it gets bogged down (the most likely outcome) or somehow pulls a rabbit out of a hat—Washington would benefit either way. Chinese President Xi Jinping, it’s your turn.

SEE THE IMPERIALIST STATE N. BUKHARIN

No comments:

Post a Comment