Matt Oliver

Fri, 9 February 2024

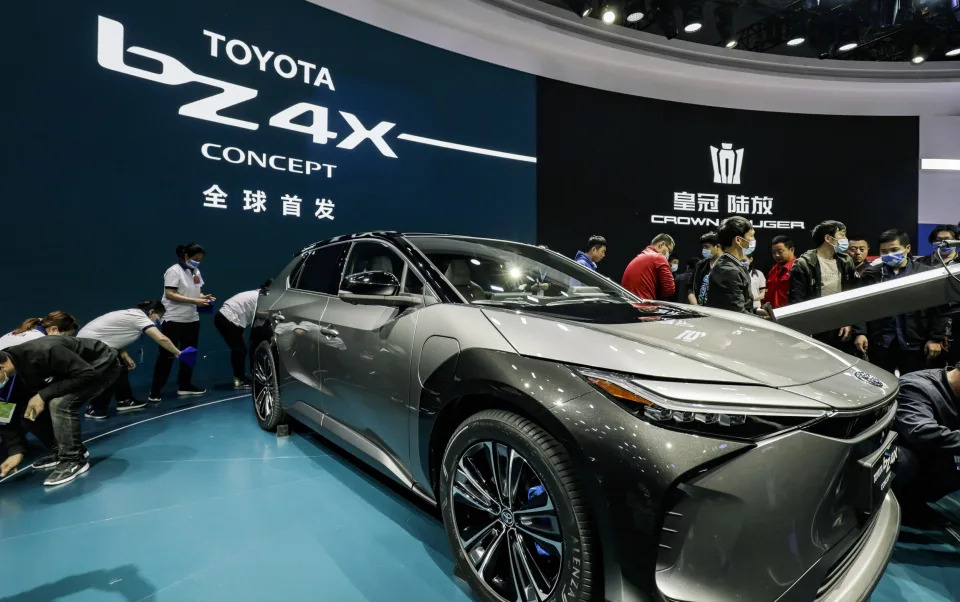

Toyota chairman Akio Toyoda believes electric cars will never account for more than a third of the market - Kiyoshi Ota/Bloomberg

Speaking to Toyota employees last month, Akio Toyoda sounded slightly bruised.

The chairman of the world’s biggest car maker described how he had been “beaten up” by critics for refusing to bet all his company’s chips on electric vehicles (EVs).

Instead, he has doggedly championed a so-called multi-pathway approach that spans EVs, hybrids and even hydrogen-powered cars.

The decision has infuriated climate activists who once praised Toyota for its eco-friendly Prius hatchback, while even industry insiders have wondered whether the company is making a strategic blunder.

“It’s really hard to fight alone,” Toyoda said to staff, according to a translation of his January remarks.

But now the industrialist’s rivals are looking on in envy, as a slowdown in EV sales has left his company in pole position to capitalise on a surge in demand for hybrids.

Toyota sold 10.3 million cars in 2023, an increase of 7.7pc compared to a year earlier.

The total included a combined 3.5 million hybrids and plug-in hybrids – a year-on-year increase of 32pc – but only 104,000 EVs.

For the year to the end of March, the Japanese giant is now forecasting profits of 4.5 trillion yen (£24bn), up from 2.5 trillion yen previously.

Yoichi Miyazaki, executive vice president at Toyota, said hybrids were even selling strongly in China – the world’s biggest market and producer of EVs.

“As a realistic solution, hybrids are still favoured by our customers,” he told reporters.

Meanwhile, rival manufacturers that have driven further ahead with EVs are now pumping the brakes, with Ford, Volkswagen and General Motors among those scaling back production.

After successfully targeting early adopters, they are finding the mass market much tougher to crack – with many consumers still put off by high prices and worries about charging infrastructure.

“EVs have soaked up all of the early adopter and wealthy demand,” explains Andrew Bergbaum, an automotive expert at consultancy AlixPartners.

“But the costs still haven’t come down to the point where they’ve reached the mass market prices you see with internal combustion engine (ICE) cars.

“Hybrids are also considerably cheaper [than EVs], because the batteries in them are so much smaller.

“Once you couple that with range anxiety and concerns about EV resale values, it’s a fairly understandable market phenomenon.”

Alongside the cheaper upfront cost compared to EVs, automotive analysts say drivers also like the fact their hybrids get more out of each tank of petrol.

Toyota’s Prius, first launched in 1997, became one of the most popular hybrid cars, with the model notching up more than five million sales globally.

The company and other proponents have long argued hybrids are an ideal bridge between petrol-only cars and pure EVs, with Toyota’s chairman noting that the company serves many markets around the world that cannot progress as quickly with electrification as Japan and the West.

In his remarks to staff last month, Toyoda noted that one billion people around the world still live in areas without electricity. “So a single [EV] option cannot provide transportation for everyone,” he is said to have added.

His critics, including Greenpeace, charge that hybrids cannot deliver a fast enough drop in emissions globally to stop catastrophic climate change, however.

None the less, even in the West the biggest barriers to EV adoption remain high prices and unevenly distributed charging infrastructure.

While a new, petrol-fuelled version of the Vauxhall Corsa – one of the UK’s most popular cars – will set you back £19,000, the EV variant costs £34,000, according to MoneySavingExpert.

Meanwhile, governments are failing to hold up their end of the bargain by ensuring there is always somewhere to charge.

The UK vowed to roll out at least six high-power charging stations to every motorway service area in England by the end of last year but missed the target woefully – with only two in five service areas meeting this standard.

Meanwhile, early adopters of EVs have been hit with sky-high insurance premiums and rapid falls in value, with used prices expected to fall by as much as half over three years.

Against this backdrop, hybrids are proving hugely popular, with sales currently growing faster than those of EVs in some markets.

UK sales of hybrids and plug-in hybrids surged 31pc higher to a combined 380,253 cars last year, according to the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT). This grew their total market share from 17.9pc to 20pc.

By comparison, sales of EVs climbed 18pc to 314,687 – but their market share shrank from 16.6pc to 16.5pc.

Over the same period, sales of hybrids in the European Union surged 30pc higher to 2.7 million units as well, fuelled by demand in Germany, France and Spain.

And while the UK and the EU are both set to ban sales of hybrids from 2035, a much bigger market is set to remain open for longer: China.

In Western markets, hybrids often sell for a few thousand dollars more than petrol cars but in China this trend has been flipped – with some auto giants selling them for 20pc less than their combustion engine counterparts.

Last year, while the number of EVs bought in China surged 38pc to 6.68 million, the number of plug-in hybrids rocketed 85pc higher to 2.8 million.

“While pure battery-powered EVs are leading the transition… sales data suggest consumers are increasingly demanding various types of hybrid vehicles that burn fossil fuels as backup,” Ernan Cui, an analyst at Gavekal Dragonomics, told The Nikkei in Japan.

What’s more, Toyota’s current hybrid advantage is not easily replicated. It takes between five and seven years to develop a new car, notes AlixPartner’s Bergbaum.

“So decisions made years ago really determine when you’re going to launch a car,” he explains. “You change that but really only by a year or so.”

Manufacturers can adjust their EV production lines, however.

“But if you don’t have a hybrid in development or production at the moment, you’re probably not going to create one – because the investment is so huge.”

Toyota’s strategy also includes continued investment in hydrogen cars, but has met far less success so far with the launch of its Mirai model. Hydrogen cars use a fuel cell instead of a battery, relying on a chemical reaction between hydrogen and oxygen for propulsion.

Like petrol vehicles, they can in theory be refilled extremely quickly. “But if you’ve actually bought one in Europe, you will find it very difficult to fill up,” Bergbaum adds.

Still, he argues, critics are wrong to charge that Toyota has taken no interest in EVs. While climate activists accuse the company of foot-dragging, it is still investing $35bn in the technology up to 2030.

By then it is hoping to have around 30 electric car models available, or around one quarter of its current lineup. At the moment just one has gone on sale, the bZ4X SUV, with underwhelming results.

A Toyota spokesman says the company “sees carbon as the enemy, not a single power-train”, adding: “Multiple solutions are offered that deliver carbon reduction – a mix of battery-electric vehicles, [plug-in hybrids], [fuel cell cars] and [hybrids] so that customers can choose what best suits them considering availability of renewable energy, infrastructure, government policy and price point.”

The company says it aims to have 10 EV models on the market by 2026, when it expects sales to reach 1.5m a year.

The bZ4X SUV is Toyota's only electric car available so far - Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

Last year Toyota claimed it had made a technological breakthrough that could cut the cost, size and weight of batteries in half – a potential game-changer.

Bosses say these solid-state batteries will deliver a 20pc improvement in so-called cruising range, for example motorway driving, and will be charged in 10 minutes or less. They are aiming to have the technology on the roads by 2027.

Should the hybrid gold rush dry up, Toyota will need this kind of innovation to distinguish itself in what is now becoming a very crowded field of EVs.

A particular threat to the company will come from China. “If you’re asking whether it was canny to have the multi-propulsion strategy and invest in solid state, it looks like it might have been,” says Bergbaum.

“But I don’t think this game has fully played out yet. Because the Chinese are now coming and selling cars that are quasi-commensurate in price to a standard ICE.

“So I think we’re soon going to see a very different dynamic in the European market.”

With emission rules also continuing to ramp up – the UK’s zero emission vehicle mandate began this year, tightening the screws on manufacturers – Toyota may also come under pressure from governments to move faster into EVs.

But that isn’t something that appeared to worry chairman Toyoda when he spoke to staff last month.

“I think this is something that customers and the market will decide,” he said. “Not regulatory values or political power.”

No comments:

Post a Comment