Image by Jon Tyson.

Writers often try to gild their tawdry times or dignify their flawed leaders with lofty literary analogies — notably, America as the New Jerusalem; Lincoln as Moses leading his people through the wilderness of the Civil War; the Kennedy White House as an incarnation of King Arthur’s “Camelot“; or Lyndon Johnson living his last years as a latter-day King Lear, cast off by his ungrateful children into the moors of south Texas.

But what are we going to do with Donald Trump? Wouldn’t his vanity, his vulgarity, and his relentless pursuit of money and minerals in every corner of the globe turn any literary analogies into soggy clichés? Like the showman P.T. Barnum, Trump is an American original, whose true metaphors can be found only in comic books (America’s one true art form), not literature. As Ariel Dorfman reminded us once upon a time in How to Read Donald Duck, that classic guide to U.S. cultural imperialism in Latin America, there was always more to a Disney comic book than gags.

To understand Trump’s America, we need our own comic guidebook to his global misadventures, which might be titled something like “How to Read Scrooge McDuck.” After all, in case you never had the pleasure of his acquaintance, Scrooge McDuck was the predatory billionaire in Disney comics, who was amazingly popular among teenagers in Cold War America. In that era when American corporations scampered around the global economy extracting profits wherever they saw fit, Scrooge McDuck put a friendly face on U.S. imperialism, making covert intervention and commercial exploitation look benign, even comic.

From 1952 to 1988, a period coinciding almost precisely with the Cold War, the comic’s creator, illustrator Carl Barks, filled the country’s magazine racks with more than 220 comic books celebrating Scrooge’s schemes to accumulate ever more billions by dispatching Donald Duck and his triplet nephews (Huey, Dewey, and Louie) to scour the world for riches — gems, minerals, oil, and lost treasure. No place on the planet was too remote, not even the Arctic or the Amazon, and no people too poor or obscure, not even Hondurans and Tibetans, to escape his tight-fisted grasp. And yet in that innocent world of the comic book, every adventure, no matter how twisted the plot, always ended with a light laugh for those duckling heroes and the diverse peoples they encountered on their global travels.

Let’s visit a few of my favorite comic books from my Cold War childhood, starting with the 1954 story “The Seven Cities of Cibola.” Its initial panels show a butler showering the billionaire duck with coins while he swims around in his Money Bin’s “three cubic acres” of cash. At first, Scrooge McDuck seems content as he gloats about making money from “about every business there is on Earth” (from “oil wells, railroads, gold mines, farms, factories”).

Suddenly, however, saddened by the realization that he’s exhausted every possible domestic path to profit, Scrooge decides to lead his nephew Donald and the triplets into the desert borderlands between Mexico and the U.S. There, they come upon a lost Eldorado, a towering, multitiered city with gold-paved streets and a cistern filled with opals and sapphires. But caution intrudes when Huey, Dewey, and Louie discover that the whole edifice is poised dangerously atop a spindly stone pillar. Then, at their moment of near triumph, the ducks are denied any treasure by Scrooge’s recurring nemesis, the comically criminal Beagle Boys, who break in and grab the city’s bejeweled idol, triggering a hidden mechanism that fractures the pillar. As those fabled cities collapse into a heap of rubble, our duckling heroes escape unharmed, ready for their next adventure.

The first panel in a 1956 comic book, the “Secret of Hondorica,” shows Scrooge McDuck pointing to a map of the Caribbean as he dispatches Donald Duck and his three nephews deep into tropical jungles near — yes, how sadly appropriate almost seven decades later — Venezuela to recover his lost deeds to the region’s rich oil wells. After crossing steep mountains and crocodile-infested creeks, the Ducks happen upon a Mayan temple filled with spear-carrying “savages” arrayed around their idol. By translating the “picture writing” on the temple walls with the help of their handy encyclopedic “Junior Woodchuck Guidebook,” the nephews deceive the natives with incantations in their own language and escape with the idol’s crown of gold.

President Donald Trump is, of course, our real-life Scrooge McDuck. Mar-a-Lago is his Money Bin. And the world is his playground for schemes to add another billion or two to his and his family’s growing fortune. Just as Scrooge McDuck scoured the world in a relentless, even ruthless search for wealth, so our real-life Donald has made mineral deals everywhere on the planet his top presidential priority — rare earths from Ukraine, oil from the Middle East, and (someday perhaps) a frozen treasure trove of minerals in Greenland. And just as Scrooge dispatched Donald Duck on a mission to recover his lost oil wells from the jungles of “Hondorica,” so our real Donald did indeed send U.S. special forces to capture President Nicolás Maduro and win yet more of Venezuela’s oil fields for American companies.

Back to the Reality of the Old Cold War

Alas, my innocent childhood is long gone. The world is no backdrop for comic book adventures and imaginary heroes don’t flit from frame to frame to amusing endings. In the real world of 2026, we are already deep into a “new Cold War” against nuclear-armed powers, and President Donald J. Trump’s comedic foreign policy is dragging us toward a dismal defeat.

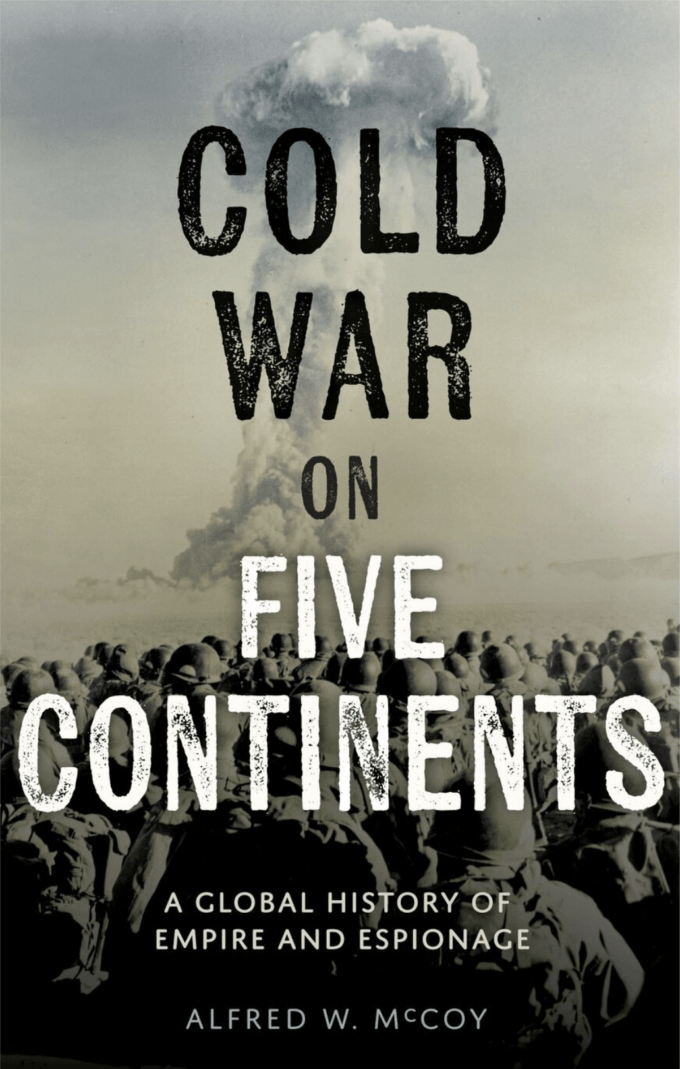

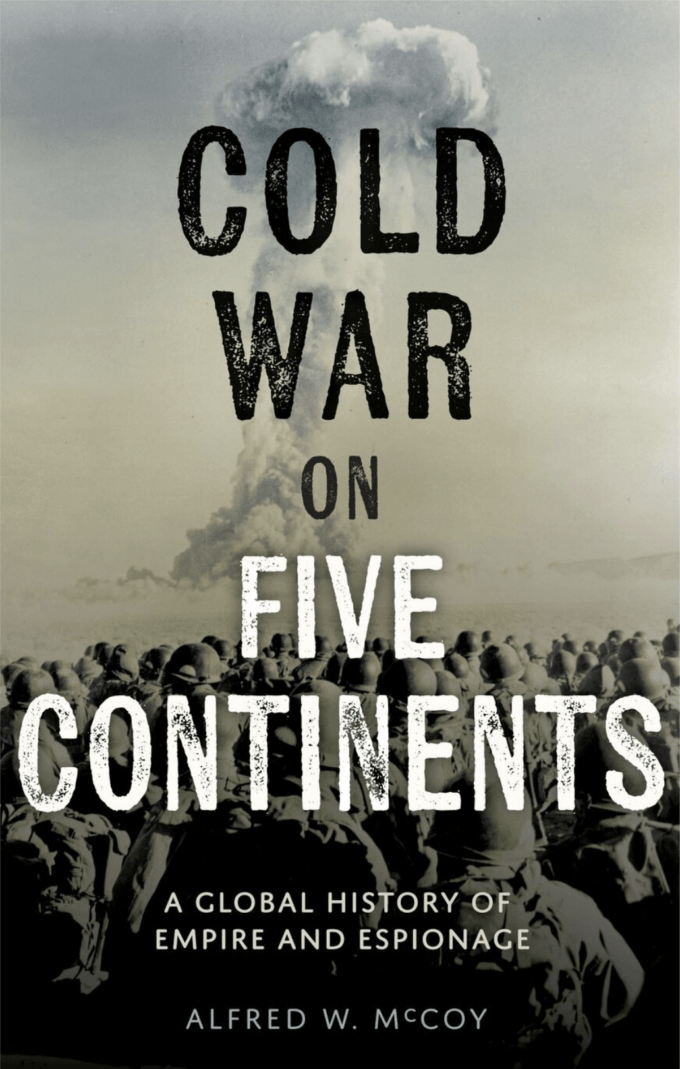

First, let’s snap back to reality by taking stock of the world we’ve actually been living through all these years and review how we got here. During the real Cold War, the global conflict that lasted from 1947 to 1991 (when the Soviet Union collapsed), the one I describe in my new book, Cold War on Five Continents, Washington’s geopolitical strategy was brilliantly ruthless in its basic design. After fighting quite a different global conflict, World War II, for four years with the aim of defeating the Axis powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) entrenched at both ends of Eurasia, America’s leaders of General (and future president) Dwight D. Eisenhower’s generation knew instinctively that geopolitical control over that vast continent was indeed the key to global power.

Guided by that fundamental strategic principle (which had, in fact, held true for the last thousand years or so), Washington’s early Cold War leaders worked hard to “contain” the Sino-Soviet communist bloc behind an “Iron Curtain” that stretched for 5,000 miles around the rim of Eurasia. With the armed forces of its NATO alliance securing that continent’s Western frontier and five bilateral military pacts ranging along the Pacific littoral from Japan to Australia for its eastern border, Washington bottled up the communist superpowers. That strategy freed the U.S. to make the rest of the planet into its very own “free world.” In exchange for open access to the markets and minerals of the countries in much of that free world, the U.S. distributed a few development dollars of aid to the emerging nations of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, which often served to fatten up the bank accounts of their nominally “democratic” dictators.

After two decades of being locked up inside Eurasia, however, Beijing and Moscow tried to break out of their geopolitical isolation by arming allies for revolutionary warfare on Cold War battlegrounds stretching from South Vietnam across the Middle East and through southern Africa, all the way to Central America.

To counter that gambit and push those communist powers back behind the Iron Curtain, the U.S. sometimes sent in its own troops, whether successfully to the Dominican Republic in 1965, or disastrously to South Vietnam from 1965 to 1973. But most of the time, Washington dispatched individual CIA operatives armed with impunity to do whatever — and I do mean whatever — they wanted to deflect Moscow’s and Beijing’s gambits and secure contested terrain. Usually misfits, even oddballs at home, those surprisingly significant historical actors, whom I’ve come to call “men on the spot,” often proved quite successful abroad. Using the cruelest instruments in the toolkit of modern statecraft — assassinations, coups, surrogate troops, torture, and psychological warfare — those covert operatives fought for control of foreign capitals as diverse as Kinshasha, Luanda, Saigon, Santiago, San Salvador, Tegucigalpa, and Vientiane. And then, with the Soviet Union significantly “contained” geopolitically within its borderlands, Washington could just sit back and wait for Moscow to make a strategic blunder.

That blunder came in 1979 in one of those classic military misadventures that often hasten the deaths of empires in decline. When Moscow sent 100,000 troops to occupy Afghanistan, Washington sent just one CIA operative, Howard Hart, to defeat that occupation. Acting as Washington’s “man on the spot,” he used the agency’s millions of dollars to form a guerrilla army of 250,000 Afghan fighters. By the time the Red Army was bled dry and left Afghanistan a decade later, defeated and demoralized, Moscow’s satellite states in Eastern Europe were erupting in mass, anti-communist protests. With the Red Army generally unable or unwilling to intervene, the Soviet bloc broke apart as the Soviet Union broke up, ending the Cold War with an unqualified U.S. victory.

Toward a New Cold War

If Washington’s strategy for waging the Cold War was a successful exercise in geopolitics, its use of “unipolar” power in the decades to come was, as I also argue in Cold War on Five Continents, much less so. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Washington stood astride the globe like a Titan of Greek legend — the sole superpower on earth, at least theoretically capable of remaking the world as it wished. Convinced that “the end of history” would make its free-market democracy the future of all mankind, America’s leaders, “drunk with power,” advanced sweeping plans for a new world order, grounded in a globalized economy that served their short-term interests but would have deleterious long-term consequences for their global hegemony.

Only a decade after the Cold War ended, Washington started facing serious strategic challenges across the Eurasian continent, which, then and now, has been the epicenter of geopolitical power. In the heady aftermath of its Cold War victory, the U.S. attempted some bold strategic gambits that would soon prove to be distinctly ill-advised. Above all, Washington’s leaders believed that they could co-opt Beijing’s rising power by recognizing China as an equal trading partner. In a parallel attempt to curb any of Moscow’s future imperial ambitions, the U.S. also presided over NATO’s expansion until that alliance surrounded Russia’s western borders, sparking security concerns in Moscow. Such ill-fated initiatives, combined with ill-considered military interventions in Afghanistan and also Iraq, created conditions for the revival of a great-power rivalry that, since Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, many observers have called “the new Cold War.”

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and its socialist economy in 1991, Washington seemed to feel its post-Cold-War globalization would both promote democracy there and integrate that country into an emerging American world order, perhaps as a secondary power supplying cheap commodities, including oil, to the global economy. For the Russians, however, such globalization produced the dismal decade of the 1990s that would be marked by what economist Jeffrey Sachs has called a “serious economic and financial crisis” and a privatization of state enterprises “rife with unfairness and corruption,” creating a coterie of predatory Russian oligarchs.

When Vladimir Putin became prime minister amid the post-Soviet malaise of the late 1990s, he reverted to Russia’s centuries-old imperial mode. He found his vision for the country’s revival as a “great power” in the sort of geostrategic thinking that Washington’s leaders seemed to have forgotten in the afterglow of their great Cold War victory. Following a 2005 address calling the collapse of the Soviet Union the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century,” Putin set about systematically reclaiming much of the old Soviet sphere — invading Georgia in 2008 when it began flirting with NATO membership; deploying troops in 2020-2021 to resolve an Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict in favor of a pro-Moscow regime in Baku; and dispatching thousands of Russian special forces to Kazakhstan in 2022 to gun down pro-democracy protesters challenging a loyal Russian ally.

Concerned above all with securing his western frontier with Europe, Putin pressed relentlessly against Ukraine after his loyal surrogate leader there was ousted in the 2014 Maidan “color revolution.” First seizing Crimea, next arming separatist rebels in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region adjacent to Russia, and finally invading Ukraine in 2022 with nearly 200,000 troops, he would spark a protracted war that has yet to end.

At first, as Kyiv fought the Russians off, Washington and the West reacted with a striking unanimity by imposing serious sanctions on Moscow, dispatching armaments to Ukraine, and expanding NATO to include all of Scandinavia. Moreover, Ukraine showed a formidable flair for unconventional operations — clearing Russian ships from the Black Sea with naval drones and sabotaging that country’s massive gas pipeline under the Baltic Sea.

As Russia’s war on Ukraine reverberated across Eurasia and beyond, geopolitical tensions also rose in the Western Pacific, sparking a renewed great power rivalry that became worthy of the phrase “the new Cold War.” In a striking parallel with the 1950s, in February 2022, just before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Beijing and Moscow forged a multi-faceted economic and strategic alliance that they claimed had “no limits.” In an eerie reprisal of the early Cold War years, Russia and China were in that way united against a Western alliance, once again led by Washington with its military forces still deployed in Western Europe and East Asia.

After two years of continuous combat in Ukraine, however, cracks began to appear in the West’s anti-Russian coalition. Most critically, American domestic support for Ukraine started to falter under partisan political pressures, amplified by a rising populist opposition in both the U.S. and Europe to the globalized economy and its military alliances. After successfully rallying NATO to stand with Ukraine, President Joseph Biden opened America’s arsenal to Kyiv until Republican legislators, at Donald Trump’s behest, delayed military aid throughout much of 2024.

President Trump’s Second Term

Following his second inauguration in January 2025, President Trump’s initial foreign policy initiative was a unilateral attempt to negotiate an end to the Russia-Ukraine war — an effort that would be complicated by his underlying hostility toward NATO and his sympathy for Russian President Putin. On February 12th, Trump launched peace talks through a “lengthy and highly productive” phone call with the Russian president, agreeing that “our respective teams start negotiations immediately.” Within days, Defense Secretary (or do I mean Secretary of War?) Pete Hegseth announced that “returning to Ukraine’s pre-2014 borders is an unrealistic objective,” and Trump added that NATO membership for Kyiv was no less unrealistic — in effect, making what a senior Swedish diplomat called “very major concessions” to Moscow before any talks even began.

At month’s end, those tensions culminated in a televised Oval Office meeting in which Trump berated Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, saying, “You’re either going to make a deal or we’re out, and if we’re out, you’ll fight it out. I don’t think it’s going to be pretty.” That unilateral approach not only weakened Ukraine’s ability to defend itself, but also degraded NATO, which had, for the previous three years, supported Ukraine’s resistance to Russia. Recoiling from the “initial shock” of that utterly unprecedented breach, Europeans quickly appropriated $160 billion to build up their own arms industry in collaboration with both Canada and Ukraine, thereby reducing their dependence on U.S. weaponry.

For the rest of the year, Putin continued to work on Trump. He even scored a state visit and meeting with the American president in Alaska, without making any concessions whatsoever. In the process, he reduced U.S. envoys to messenger boys for his unyielding demands, while using disinformation to drive a wedge between Washington and Kyiv. Even if the Trump administration does not formally withdraw from NATO in the years to come, the president’s repeated hostility towards it, particularly its crucial mutual-defense clause, may yet serve to weaken, if not eviscerate the alliance.

Amid a torrent of confusing, often contradictory foreign policy pronouncements from the White House, the design of Trump’s de facto geopolitical strategy soon took shape. Instead of focusing on mutual-security alliances like NATO in Europe or NORAD with Canada, Trump seems to prefer a globe divided into three major regional blocs, each headed by an empowered leader like himself — with Russia dominating its European periphery, China paramount in Asia, and the United States controlling the Americas. That aspiration to hemispheric hegemony lent a certain geopolitical logic to Trump’s otherwise quixotic strikes on Venezuela (and his capture of its president and his wife), as well as his overtures to claim Greenland, reclaim the Panama Canal, and even to make Canada the 51st state.

Last November, formalizing that approach, the White House released its new National Security Strategy, which proclaimed a “Trump Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine” aimed at achieving an unchallenged “American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere.” Think, of course, the Donroe Doctrine. To that end, the U.S. will reduce its “global military presence to address urgent threats in our Hemisphere,” deploy the U.S. Navy to “control sea lanes,” and use “tariffs and reciprocal trade agreements as powerful tools” to make the Western Hemisphere “an increasingly attractive market for American commerce.” In essence, “the United States must be preeminent in the Western Hemisphere as a condition of our security and prosperity.”

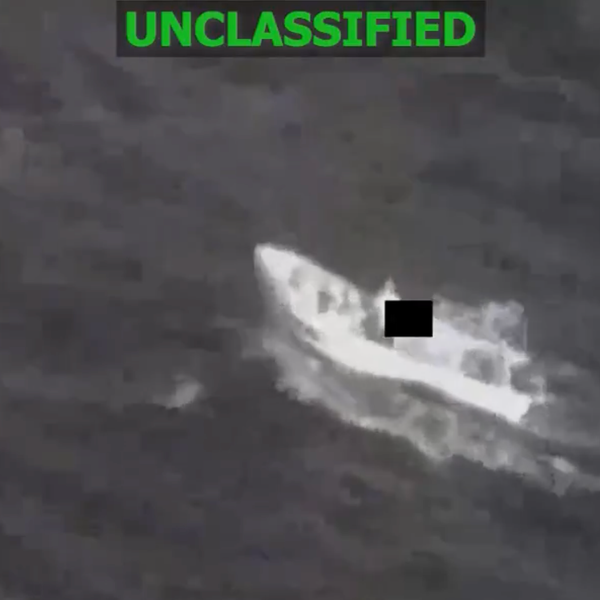

For over a century, the Caribbean region had consistently experienced the most brutal, least benign aspects of U.S. foreign policy and now that reality has only worsened. Not only has Trump reverted to the gunboat diplomacy of Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, but he’s done so with a caricatured cruelty — sinking boats in the Caribbean in the name of drug interdiction and sending troops to invade Venezuela, a sovereign state.

Just as Theodore Roosevelt used the Navy to seize land from Colombia for the Panama Canal, so Trump sent Special Forces into Venezuela to gain control over its oil. “We’re going to have our very large United States oil companies… go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure, the oil infrastructure, and start making money for the country,” Trump said at a January 3rd press conference just hours after President Maduro’s capture. “We’re gonna rebuild the oil infrastructure, which will cost billions of dollars. It will cost us nothing. It’ll be paid for by the oil companies directly.” Such a caricatured assertion of economic interest is likely to inflame resentment in a region where anti-imperialist sensibilities remain strong.

Although it has little chance of success, Trump’s attempt at a tricontinental grand strategy will likely leave a residue of ruin — alienating allies in Latin America, weakening NATO’s position in Western Europe, and ultimately corroding Washington’s global power. From a strategic perspective, a staged U.S. retreat from its military bastion in Western Europe would end its long-standing influence over Eurasia, which remains the epicenter of geopolitical power in this new Cold War era, just as it was in the old one. Such a retreat, at the very moment when Russia and China are expanding their influence over that strategic continent, would be tantamount to a self-inflicted defeat in this era of a new and intensifying Cold War.

To return to those Donald Duck comic books for an appropriate analogy: just as that bungled grab for a bejeweled idol collapsed the spindly stone pillar holding up the “Seven Cities of Cibola,” so the Trump administration’s inept foreign policy is potentially destabilizing a fragile world order with dangerously unpredictable consequences for us all. And count on one thing, unlike in the comic books, it won’t be even a little bit funny.

This piece first appeared on TomDispatch.