Vampires in the deep: An ancient link between octopuses and squids

A 'genomic living fossil' reveals how evolution of octopuses and squids diverged more than 300 million years ago

image:

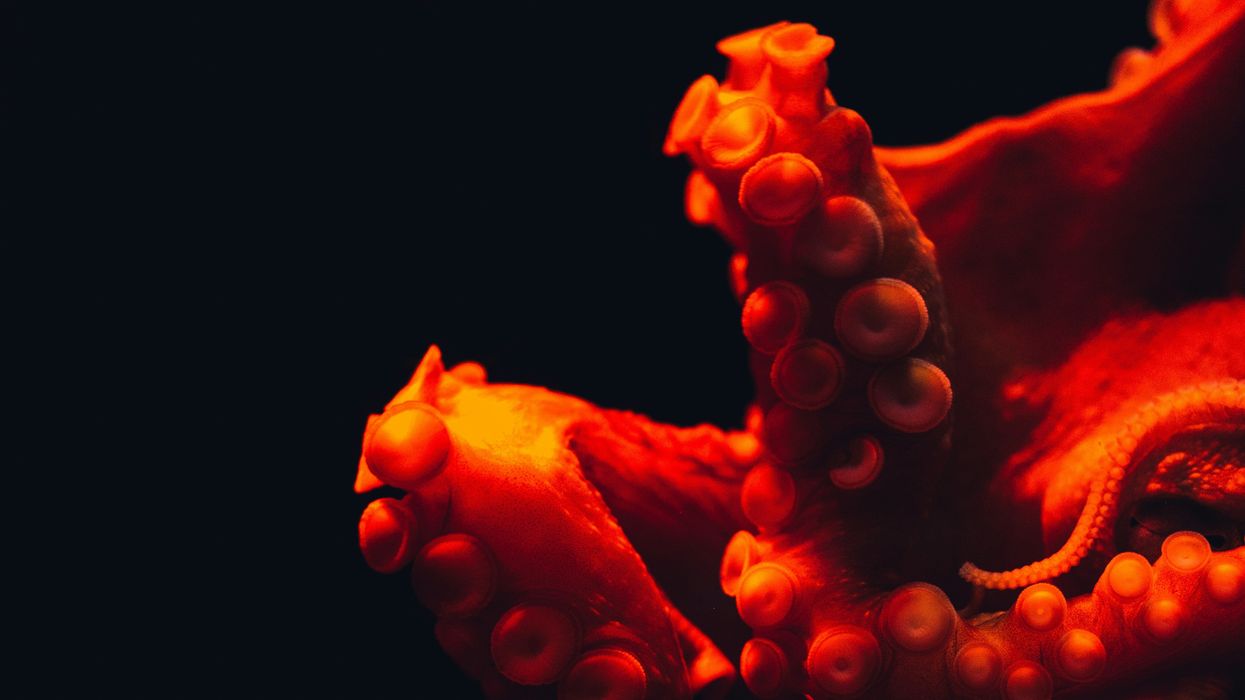

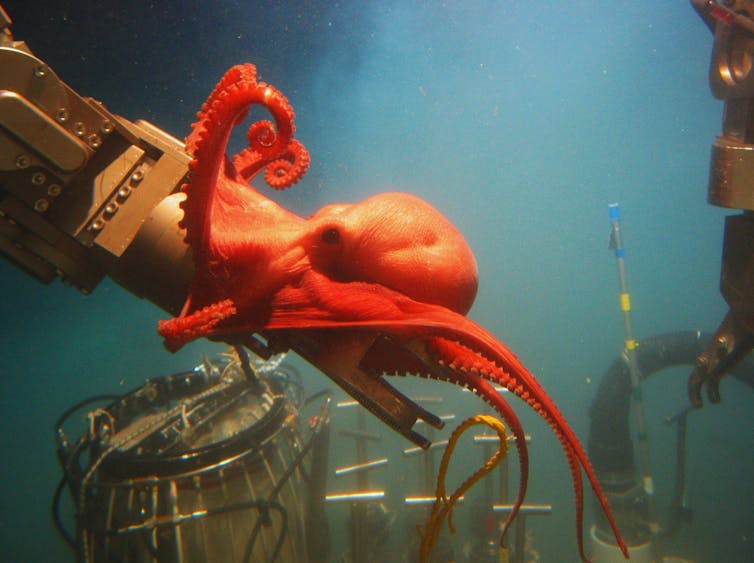

The vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis sp.) is one of the most enigmatic animals of the deep sea.

view moreCredit: Steven Haddock_MBARI

In a study now published in iScience, researchers from the University of Vienna (Austria), National Institute of Technology - Wakayama College (NITW; Japan), and Shimane University (Japan) present the largest cephalopod genome sequenced to date. Their analyses show that the vampire squid has retained parts of an ancient, squid-like chromosomal architecture, and thus revealing that modern octopuses evolved from squid-like ancestors.

The vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis sp.) is one of the most enigmatic animals of the deep sea. With its dark body, large eyes that can appear red or blue, and cloak-like webbing between its arms, it earned its dramatic name – although it does not suck blood, but feeds peacefully on organic detritus. "Interestingly, in Japanese, the vampire squid is called "kōmori-dako", which means 'bat-octopus'", says one of three lead PIs of this project, Masa-aki Yoshida, Shimane University. Yet its outward appearance hides an even deeper mystery: despite being classified among octopuses, it also shares characteristics with squids and cuttlefish. To understand this paradox, an international team led by Oleg Simakov from the University of Vienna, together with Davin Setiamarga (NITW) and Masa-aki Yoshida (Shimane University), has now decoded the vampire squid genome.

A glimpse into deep-sea evolution

By sequencing the genome of Vampyroteuthis sp., the researchers have reconstructed a key chapter in cephalopod evolution. "Modern" cephalopods (coleoids) – including squids, octopuses, and cuttlefish – split more than 300 million years ago into two major lineages: the ten-armed Decapodiformes (squids and cuttlefish) and the eight-armed Octopodiformes (octopuses and the vampire squid). Despite its name, the vampire squid has eight arms like an octopus but shares key genomic features with squids and cuttlefish. It occupies an intermediate position between these two lineages – a connection that its genome reveals for the first time at the chromosomal level. Although it belongs to the octopus lineage, it retains elements of a more ancestral, squid-like chromosomal organization, providing new insight into early cephalopod evolution.

An enormous genome with ancient architecture

At over 11 billion base pairs, the genome of the vampire squid is roughly four times larger than the human genome – the largest cephalopod genome ever analyzed. Despite this size, its chromosomes show a surprisingly conserved structure. Because of this, Vampyroteuthis is considered a "genomic living fossil" – a modern representative of an ancient lineage that preserves key features of its evolutionary past. The team found that it has preserved parts of a decapodiform-like karyotype while modern octopuses underwent extensive chromosomal fusions and rearrangements during evolution. This conserved genomic architecture provides new clues to how cephalopod lineages diverged. "The vampire squid sits right at the interface between octopuses and squids," says the senior author Oleg Simakov from the Department of Neurosciences and Developmental Biology at the University of Vienna. "Its genome reveals deep evolutionary secrets on how two strikingly different lineages could emerge from a shared ancestor."

Octopus genomes formed their own evolutionary highway

By comparing the vampire squid with other sequenced species, including the pelagic octopus Argonauta hians, the researchers were able to trace the direction of chromosomal changes over evolutionary time. The genome sequence of Argonauta hians ("paper nautilus"), a "weird" pelagic octopus whose females secondarily obtained a shell-like calcified structure, was also presented for the first time in this study. The analysis suggests that early coleoids had a squid-like chromosomal organization, which later fused and compacted into the modern octopus genome – a process known as fusion-with-mixing. These irreversible rearrangements likely drove key morphological innovations such as the specialization of arms and the loss of external shells. "Although it is classified as an octopus, the vampire squid retains a genetic heritage that predates both lineages," adds second author Emese Tóth, University of Vienna. "It gives us a direct look into the earliest stages of cephalopod evolution."

Revisiting cephalopod evolution

The study provides the clearest genetic evidence yet that the common ancestor of octopuses and squids was more squid-like than previously thought. It highlights that large-scale chromosomal reorganization, rather than the emergence of new genes, was the main driver behind the remarkable diversity of modern cephalopods.

About the University of Vienna:

For over 650 years the University of Vienna has stood for education, research and innovation. Today, it is ranked among the top 100 and thus the top four per cent of all universities worldwide and is globally connected. With degree programmes covering over 180 disciplines, and more than 10,000 employees we are one of the largest academic institutions in Europe. Here, people from a broad spectrum of disciplines come together to carry out research at the highest level and develop solutions for current and future challenges. Its students and graduates develop reflected and sustainable solutions to complex challenges using innovative spirit and curiosity.

Journal

iScience

Article Title

Giant genome of the vampire squid reveals the derived state of modern octopod karyotypes

Article Publication Date

21-Nov-2025