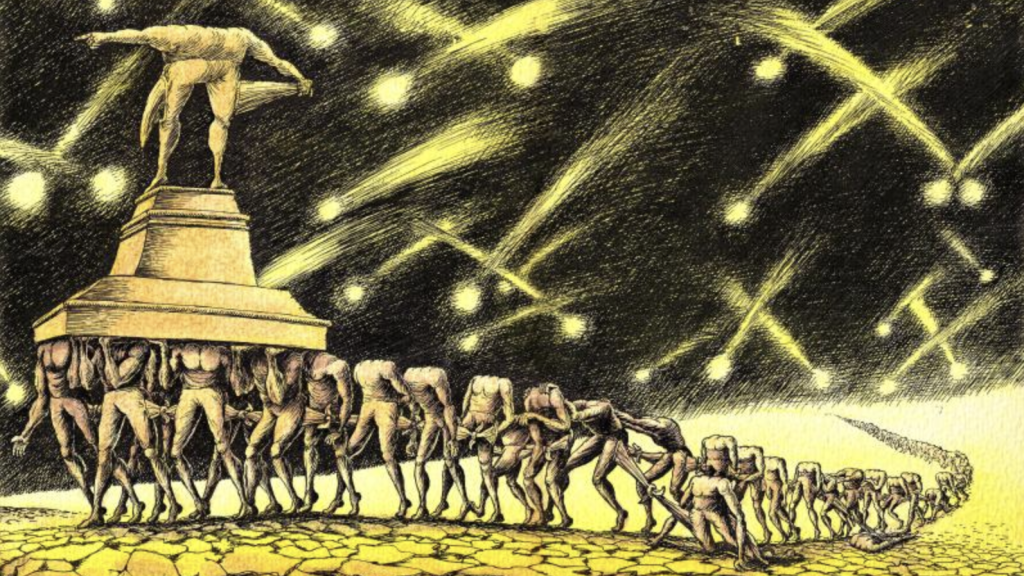

[T]he strongest and most efficient of megamachines can be overthrown[…] The collapse of the Pyramid Age proved that the megamachine exists on a basis of human beliefs, which may crumble, of human decisions, which may prove fallible, and human consent, which, when the magic becomes discredited, may be withheld. The human parts that composed the megamachine were by nature mechanically imperfect: never wholly reliable.[1]~Lewis Mumford

There is one thing that the status quo manages to do well – to convince us that achieving radical social change is an unreachable utopia. It presents itself as pragmatic and realistic, as a pillar of stability. Furthermore, it also claims a hegemony on the social imaginary level, as the only imaginable system. This is what Mark Fisher has termed Capitalist Realism – the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it.[2]

By exercising domination over every aspect of our lives – from economics to culture etc. – it proceeds into setting the parameters along which we evaluate. Thus, we learn from a very young age to perceive authority, efficiency, rapidity, and growth as the main variables to use when measuring events and experiences. For example, one is being encouraged to view the animal world not as a complex cyclical system of mutual aid, diversity and interdependence, but as a “kingdom” determined by a food chain that positions species, on the basis of their physical strength and domination, at the top or the bottom of a hierarchical scheme.

‘Stalinist realism’ and ‘escapist utopianism’

Occurrences and potential alternatives are viewed through such lens by the dominant imaginary, and when they don’t abide by the parameters of the status quo, they are simply omitted from the horizon, or at best, described as naive utopias that are best suited for naive dreamers, not for pragmatic individuals.

Even when collective activity manages to establish a rupture with the dominant order, giving space to a different set of values, it still continues to be framed by the forces of domination along their own criteria, so that their ideological hegemony remains unchallenged. An example of this can be found in the way the Haitian Revolution, one of the most significant revolutionary events to date, was perceived during its time. As Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot explains:

administrators, politicians, or ideologues found explanations that forced the rebellion within their worldview, shoving the facts into the proper order of discourse… [T]he insurrection became an unfortunate repercussion of planters’ miscalculations…[or] It was the unforseen consequence of various conspiracies connived by non-slaves[…][3]

The events that shook up Saint-Domingue from 1791 to 1804 constituted a sequence for which not even the extreme political left in France or in England had a conceptual frame of reference.[4]

This process continues to this day with varying degrees of success throughout the years. Despite the fact that increasing amounts of people believe less and less in the contemporary representative top-down model of social organization, as can be seen from the rising levels of abstention from electoral processes around the world[5], nonetheless there still is a persistent tendency among self-proclaimed revolutionaries that find it unimaginable to go beyond bureaucracy. Psychoanalyst Ian Parker has coined the term ‘Stalinist realism’ to best describe this persisting trend. According to him:

Capitalism, and the kind of ‘capitalist realism’ that tells you that there is no alternative, was mirrored by Stalinism and a ‘stalinist realism’ that tells you that the only alternative is oppressive and controlling.[…] As an ideological force stalinist realism insisted that the only reality was either capitalism or bureaucratic control, that these two systems should peacefully coexist, and not interfere with the functioning of each ‘camp’ or part of the world. If you took sides, you were told, it is one side or the other, either with capitalism or with the bureaucracy.[6]

For these-so called “realists” a social change that abolishes domination and hierarchy altogether is nothing but utopia for naive dreamers, or even as ideological cover for “agents” that want to undermine the Revolution. They don’t shy away from presenting analytical programs for today, without taking into consideration any long-term, maximum goals. Because of this, their programmatic proposals are deeply submerged into reformism of what currently exists. By being unable to think beyond top-down structures, such tendencies are destined to reproduce the oppressive ways of the current system. It is not by chance that actually existing socialism has provided us with nothing but anti-examples.

On the flip-side of the political “realists” are the so called “utopian escapists”. In a way, they too have accepted that a revolutionary alternative to the status quo is a utopia – an event so distant in the future that is practically unreachable. As a result of this understanding, they more often than not engage in lifestyle endeavors, directed at making their individual experiences “feel” somewhat alternative to the mainstream, without really challenging the Capital-Nation-State complex. As Murray Bookchin suggests, such tendencies:

seek to transform society by creating so-called alternative economic and living situations [so as] to gently edge social development away from privately owned enterprises—banks, corporations, supermarkets, factories, and industrial systems of agriculture—and the lifeways to which they give rise, into collectively owned enterprises and values. It does not seek to create a power center that will overthrow capitalism; it seeks rather to outbid it, outprice it, or outlast it, often by presenting a moral obstacle to the greed and evil that many find in a bourgeois economy.[7]

By keeping their visions for a better society in the unforeseeable future, they run the risk of descending into ideological purity. Thus, a vision of this sort begins being seen as something that needs to be kept “clean” from what currently exists. This is a kind of activist elitism that doesn’t seek the broadest possible involvement of common people, but rather to limit its reach to those who “already know” and who will not “stain” it with the ills of society-as-it-is. Jonathan Matthew Smucker aptly points at the limitations of such approaches:

There are perfectly legitimate and understandable reasons why many of us gravitate toward spaces where we feel more understood and choose the path of least resistance in the other spheres of our lives. But when we do not contest the cultures, beliefs, symbols, narratives, etc. of the existing institutions and social networks that we are part of, we also walk away from the resources and power embedded within them. In exchange for a shabby little activist clubhouse, we give away the whole farm. We let our opponents have everything.[8]

As can be seen from the above, both categories leave the current system unchallenged: they either struggle for minor reforms without challenging domination, or they attempt at creating their own elitist spaces where there is as little involvement with the broad society. They play along with the dominant narrative that wants us to believe that what currently exists is the only way (Thatchers’ famous ‘There Is No Alternative’ mantra). For a project to be truly revolutionary then, it must aim at challenging the dominant ideology of TINA and offer an alternative path to what currently exists. As Fisher suggests:

emancipatory politics must always destroy the appearance of a ‘natural order’, must reveal what is presented as necessary and inevitable to be a mere contingency, just as it must make what was previously deemed to be impossible seem attainable.[9]

A programmatic synthesis

Stripping the status quo of its inevitability means departing from the realms of both ‘stalinist realism’ and ‘escapist utopianism’. Instead, the calls for autonomy, direct democracy, and social ecology should be perceived not as visions of utopia, but as a political project that has existed to a different degree in certain historic moments, or that is currently being fought for by grassroots movements around the world. As Cornelius Castoriadis emphasizes:

Utopia is something that has not and cannot take place. What I call the revolutionary project, the project of individual as well as collective autonomy (the two being indissociable), is not a utopia but, rather, a social-historical project that can be achieved; nothing shows that it would be impossible. Its realization depends only upon the lucid activity of individuals and peoples, upon their understanding, their will, their imagination.[10]

For this democratic and ecological project to be made into living reality, social movements and grassroots collectives must not be afraid of charting their own agendas, road maps, and programs. For too long has such strategic thinking been claimed solely by the so called ‘political realists’, while refuted in one way or another by the ‘utopians’. But in fact, setting our own agenda democratically and from below does not mean bending to the self-serving will of bureaucracy. It means synthesizing our theoretical visions with political praxis in the here and now.

One such programmatic approach should have a set of maximum demands, such as the total replacement of State and capitalism by a coherent and multilayered system of direct democracy where all get an equal share in exercising power, reflected simultaneously by a set of minimum demands that bear the spirit of the former and can prove as stepping stones toward our desired destination, such as revocability of officials, inclusion of town hall meetings as a legitimate and recognized source of power in local self-governance, initiation of citizen initiative from below, participatory budgeting, appointment by lot of office-holders, and any other proposal that seeks to empower society at large. In this way immediate and long-term goals are in direct connection with each other, reflecting a popular strive for autonomy.

Scandinavian social ecologists Eirik Eiglad suggests:

Communalist organizations must develop programs and thereby bring their philosophical approach from the realm of social analysis and theory to the realm of political activism. Programmatic demands can present radical municipalist ideas in a clear and concise manner. More specifically, those demands must range from our ideal of a future society to our most immediate concerns. In revolutionary theory this escalation has been properly designated as maximum demands and minimum demands, as well as the necessary transitional demands.

These programs have to be flexible and adapted to local situations, addressing the pressing needs of the time by offering radical solutions to immediate problems. But although the minimum demands must be applied locally and regionally, certain maximum demands are required if the program is to remain communalist, such as the abolition of all forms of hierarchy and domination, the establishment of municipal confederations, and the implementation of a new system of moral economics.[11]

The question of local context is crucial for avoiding dogmatism. Such a programmatic approach must be an endeavor of social movements and communities in struggle, and not of experts and ideologues. There cannot be one-fit-all blueprint, since this would mean to fall into the trap of bureaucratic thinking. It is up to local communities, through grassroots participatory processes, to determine what are the immediate steps, most suitable to their local context, that can get them on a path toward the establishment of a truly democratic and ecological society.

One such approach also asks us to reconsider the way we approach time as regarding social change. The dream of an overnight spontaneous revolution must be abandoned – every revolutionary event we know of has been predated by long periods of patient and passionate organizational work done by individuals and collectives who dared to challenge the order of the day and advance a political alternative. Because of this we cannot but agree with Jean-Jacques Rousseau that the citizen should arm himself with strength and steadfastness[12], as well as with Castoriadis when saying that everything must be remade at the cost of a long and patient labor[13].

A programmatic approach is also an indispensable tool for public intervention, as it offers movements and initiatives a coherent message with specific proposals and a sense of long-term direction that can convey to common people a conviction in a possible alternative and a motivation for praxis. Without such intervention into the public sphere nothing can be achieved, as social change in the direction of direct democracy requires large segments of society to begin mobilizing and organizing toward that end, rather than than small sects conspiring in secrecy. Being well aware of this, Bookchin insists that for one movement to become truly public it needs to formulate a politics that opens it to social intervention, that bring it into the public sphere as an organized movement that can grow, think rationally, mobilize people, and actively seek to change the world.[14] He further suggests that:

[W]e must ask ourselves what mode of entry into the public sphere is consistent with our vision of empowerment. If our ideal is the Commune of communes, then I submit that the only means of entry and social fulfillment is a Communalist politics with a libertarian municipalist praxis; that is, a movement and program that finally emerges on the local political scene as the uncompromising advocate of popular neighborhood and town assemblies and the development of a municipalized economy. I know of no other alternative to capitulation to the existing society.[15]

One practical example of this approach can be found in the Slovenian city Maribor. For over 10 years there has been functioning the so-called Initiative for Citywide Assembly (Iniciativa mestni zbor – IMZ).[16] It is focused on organizing and sustaining non-partisan, self-organized municipal assemblies in the city. So far, the initiative has around 10 assemblies in different neighborhoods that meet regularly and are attended by common citizens. It pushes for these grassroots institutions to be accepted and recognized by authorities as a standard form of communication and collaboration amongst people, giving them a voice on matters that affect their locality, as well as the right to exercise participatory budgeting. What they aim at is the real-life reclamation of power by local communities. This goal represents a synthesis of the long-term striving for direct democracy, where institutions of the people replace the bureaucratic state, with the more immediate one of empowering citizens in the here and now, by setting up the proper tools with which to begin having some input on local decision-making processes.

In conclusion, being a political ‘realist’ or seeking for a ‘perfect end-state’ both limit the scope of action. Either case leaves dominant parameters intact, seemingly unalterable. Recommencing the revolutionary project, i.e. setting direct democracy as a horizon, means abandoning the aforementioned logics, embracing instead the complexity and messiness of trying to implement it in the here and now. Organizing our communities horizontally and managing to draft collectively our own programmatic agendas helps us break the supposed juxtaposition between political visions of a better society and what is politically feasible in the meantime. It is through one such process that we can really challenge the status quo. As Aki Orr suggests,

Opposing oppression and exploitation without proposing alternative political system leaves the ruling system intact. The system acts, the opposition reacts. Those who struggle against evils of a political system but do not offer an alternative to that system are politically impotent.[17]

[1] Lewis Mumford: The Myth of the Machine: Technics and the Human Development (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Inc., 1967), p230.

[2] Mark Fisher (2010): Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Winchester: Zero Books, 2010), p2.

[3] Michel-Rolph Trouillot: Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 2015), pp91-92.

[4] Michel-Rolph Trouillot: Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 2015), p82.

[5] https://www.essex.ac.uk/news/2021/09/22/voter-turnout-is-declining-around-the-world

[6] Ian Parker: ‘Stalinist Realism Part 1’ in Anticapitalist Resistance [available online at https://anticapitalistresistance.org/stalinist-realism-part-1/]

[7] Murray Bookchin: Thoughts on Libertarian Municipalism in Institute for Social Ecology [available online at https://social-ecology.org/wp/1999/08/thoughts-on-libertarian-municipalism/]

[8] Jonathan Matthew Smucker: ‘What’s wrong with activism?’ in Beyond the Choir [available online at https://jonathansmucker.org/2012/07/23/whats-wrong-with-activism/]

[9] Mark Fisher (2010): Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Winchester: Zero Books, 2010), p17

[10] Cornelius Castoriadis: A Society Adrift: More Interviews and Discussions on The Rising Tide of Insignificancy, Including Revolutionary Perspectives Today (unauthorized translation), p5. [available online at http://www.notbored.org/ASA.pdf]

[11] Eirik Eiglad: ‘Bases for Communalist Programs’ in Communalism Vol. 6 (March 2005) [available online at https://ecotopianetwork.wordpress.com/2010/07/29/bases-for-communalist-programs-eirik-eiglad/]

[12] Jean Jacques Rousseau: The Social Contract (Ware: Wordsworth Editions, 1998). P68

[13] Cornelius Castoriadis: Political and Social Writings, Vol.3 (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press), p48.

[14] Murray Bookchin: The Next Revolution: Popular Assemblies & The Promise of Direct Democracy (London: Verso, 2015), p63.

[15] Ibid

[16] Alexandria Shaner: ‘IMZ: 10 Years of Citizens Assemblies’ in Znet [available online at https://znetwork.org/znetarticle/imz-10-years-of-citizens-assemblies/]

[17] Aki Orr: Autonarchy – Direct Democracy For the 21st Century (self-published, 1996) [available online at https://web.archive.org/web/20190517032506/http://www.autonarchy.org.il/]