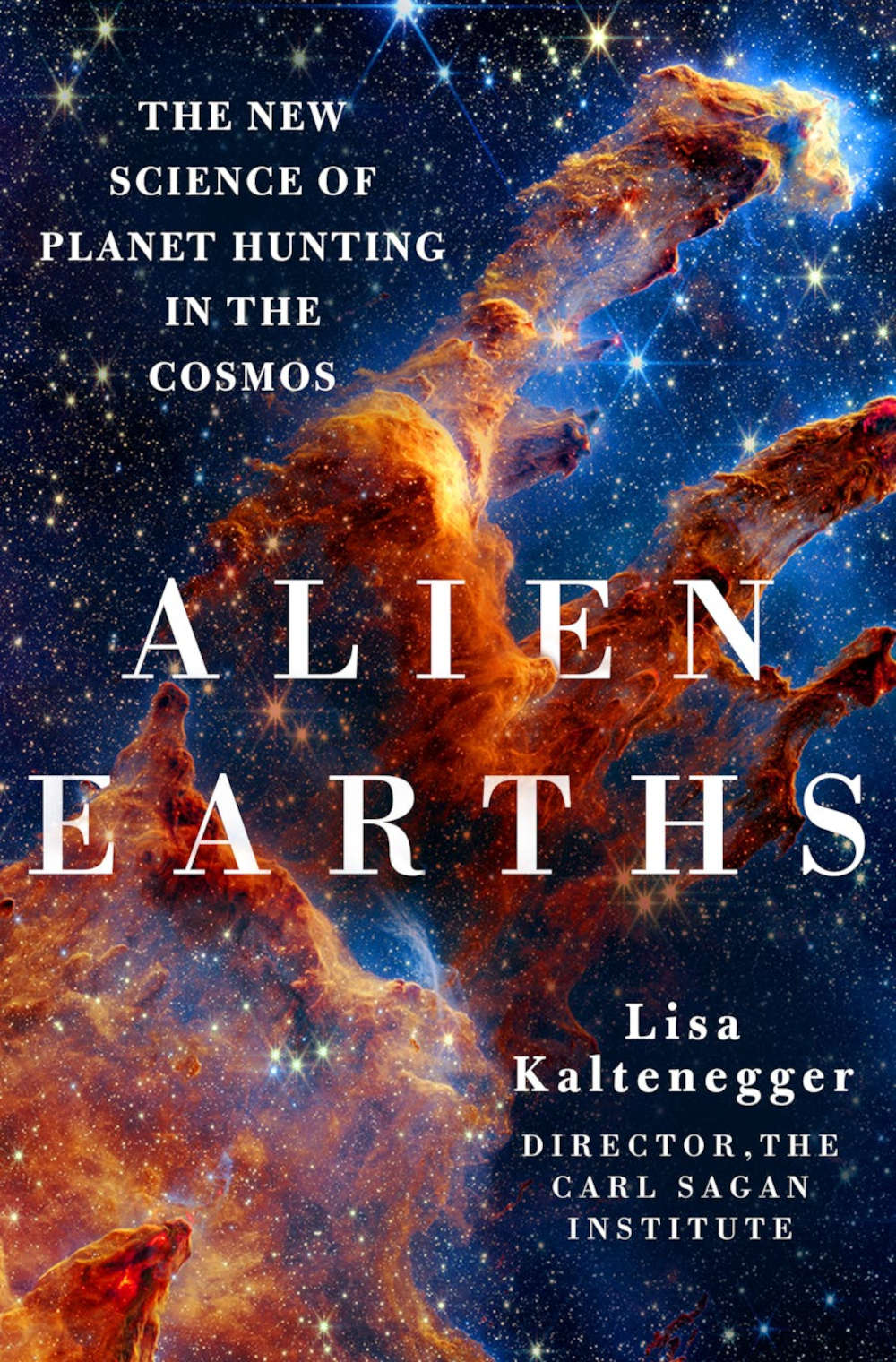

In her new book, astronomer Lisa Kaltenegger explores how scientists might find life elsewhere in the universe.

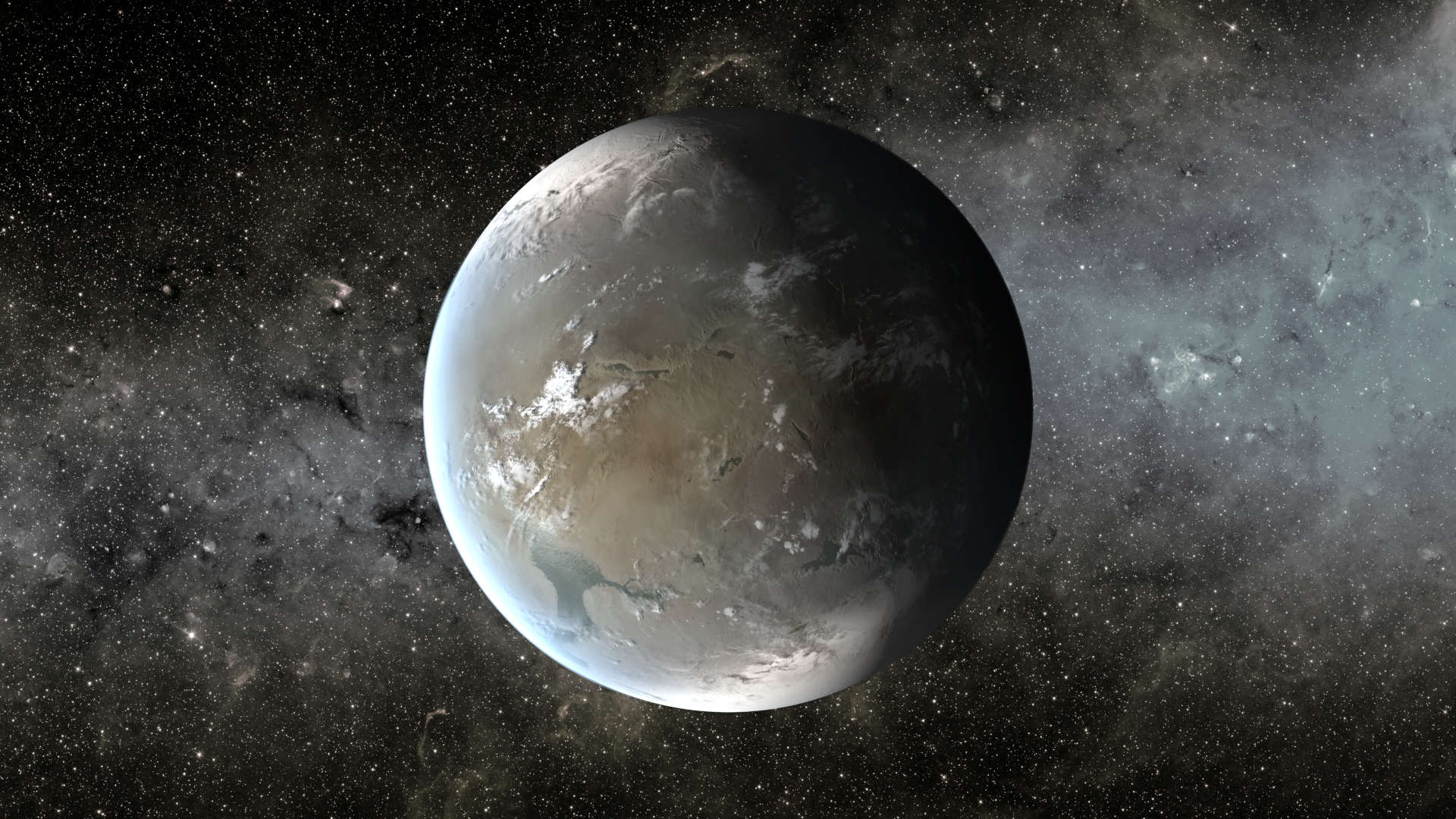

An artist’s depiction of the planet Kepler-62f, which is in the habitable zone of a star about 1,200 light-years from Earth. Visual: NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech

BY SARAH SCOLES

04.26.2024

LISA KALTENEGGER’S lab has a bit more color than a typical research facility, filled as it is with a plethora of bright glassware. It’s the kind of rainbow array you might expect to see in the lab of a life scientist. But Kaltenegger isn’t a life scientist, nor is she cultivating colorful organisms in these tiny, transparent homes for biological study. She’s an astronomer, interested in learning how masses of microbes located on distant planets might look through a telescope.

Kaltenegger has populated Petri dishes and other vessels with organisms like algae, samples of which she cajoled out of her life science colleagues at Cornell University. Each species changes the hue of its environment in a particular way, transforming the deserts, ice, or hot springs from which it came — or, in this case, the color scheme of Kaltenegger’s lab. Ocean algae, for example, can create a crimson bloom, while some hot-sulfur-spring-dwellers produce a mustard shade.

Kaltenegger’s lab is part of the interdisciplinary Carl Sagan Institute, which she founded in service of finding life in the universe. Her new book “Alien Earths: The New Science of Planet Hunting in the Cosmos” details the research that aims to find such life forms, and understand the planets they may inhabit — a pursuit that, for her, sometimes begins with those colorful organisms.

After a given group of organisms has grown enough, Kaltenegger and colleagues load it into a backpack and take it to Cornell’s civil engineering department. There, the scientists can use remote-sensing equipment to see the samples as a telescope would — measuring the different color patterns of light that result. That way, the idea goes, scientists can recognize potential alien organisms — which could, hypothetically, resemble algae and algae’s alterations of Earth — at a distance, based on their chromatic fingerprints.

“Once you try to find life somewhere else, you realize it is not so straightforward. Welcome to the world of science.”

The information about their color then gets plugged into computer models that Kaltenegger creates of planets, both actual and hypothetical. “A few keystrokes let me move the planet closer to the star, manipulate the color of its sun, heighten its gravity, create worldwide sand dunes, oceans, or jungles, and add or remove life-forms,” Kaltenegger writes. “I am creating worlds that could be and the light fingerprints to search for them with our telescopes.”

In “Alien Earths,” Kaltenegger lays out the state and stakes of this search, while exploring the array of planets in this solar system and beyond, all with the goal of answering that ultimate query: Are we alone? “The question should have an obvious answer: yes or no,” she writes. “But once you try to find life somewhere else, you realize it is not so straightforward. Welcome to the world of science.”

KALTENEGGER BEGINS “Alien Earths” by setting up the different ways that people have thought about life in the universe — or, rather, the lack of evidence for it so far. But the book’s substance is in investigating how and where life might appear in the universe, and how humans might recognize it. In this pursuit, it bounces from planetary evolution to exoplanet studies, from biological evolution to telescope technology, the text as interdisciplinary as her institute.

It’s a lot of ground to cover, and the flow of the book is not always tightly organized in a thematic way. But what the book may lack in structural coherence, it makes up for in vivid details that take readers to the titular worlds — and can lead them to view their own planet at a remove, as an alien would through its own telescope.

Take the imaginary planet that begins the book: One where a whole hemisphere is always dark, the other always light: “You wait for the sunset and the darkness of night, but they never come,” she writes. “To experience nightfall, you have to travel for days to the far side of this distant planet, a place of eternal dusk.”

Lisa Kaltenegger and her colleagues recently found that purple could be a key color to look for as a sign of life. Planets that get little or no visible light or oxygen may be covered by bacteria that use infrared light for photosynthesis and contain purple pigments. Visual: Cornell University/YouTube.

The text shines most when Kaltenegger writes about her own research, which is fascinating in its inventiveness. In the digital planets she creates, informed by her experiments, she acts as a kind of god, manipulating them to her liking and curiosity. “I can cover the oceans with a green algae bloom or dot continents with yellow microbial mats,” she says. “Without leaving my office, I can create new worlds.”

Kaltenegger explains this complex science in a straightforward, sometimes lyrical, and often humorous way. For instance, when discussing whether and how humans might communicate with extraterrestrial life, she writes that “the experience might end up being like a human trying to talk to a jellyfish. I’ve attempted that; the results were less than promising.”

The book also doles out the kind of big-picture cosmic facts that blow the minds of each new generation of pop-science readers, as when she discusses how the speed of light affects our perception of the stars: “Because light needs time to travel through the cosmos, you can find a link to your own past in the sky,” she writes. “There is a star in the night sky whose light was sent out when you were born and is just arriving now.”

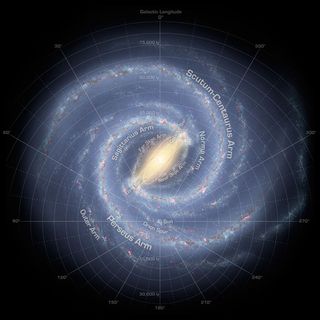

Sometimes, the humor and the mindblowers come in one package, as in Kaltenegger’s description of the solar system whizzing around the galaxy’s center. “If you ever feel stuck,” she writes, “remember: cosmologically speaking, you are not. You are speeding through the cosmos. And you are part of it.”

In that cosmos, scientists have found more than 5,000 distant planets in the past 30 years, a wave of discoveries that Kaltenegger charts, with descriptions as rich as her imagined creations. For example, the planet CoRoT-7 b, discovered in 2009, is so hot that it melts its own rocks. These liquefied rocks evaporate, then fall back down to the cursed ground as lava rain.

Kaltenegger has experimented with a similar lava planet in her lab, to again understand how a telescope might see such a place: Her team picked 20 different rock varieties that might be found on planets, then mixed them in powder form to get the compositions for the type of planet they wanted to create. When placed on a heated metal strip, they become small-scale lava — a linear lava planet, of sorts. “The worlds we create are so small, they can easily fit in the palm of my hand,” Kaltenegger writes. She and colleagues then try to figure out how that lava would look large-scale to a telescope, so they can compare that signature to sights they actually see.

“If you ever feel stuck, remember: cosmologically speaking, you are not. You are speeding through the cosmos. And you are part of it.”

Readers may be surprised, though, to find that so much of “Alien Earths” focuses on this Earth and its close neighbors in the solar system. “When we look for life in the cosmos, Earth is our lone key to unlock the secrets of what it requires to get started,” Kaltenegger explains. And so exoplanet scientists actually spend a lot of their time looking closer to home — at the blooming life in their own Petri dishes, the evolution of familiar continents, the record of meteorite strikes, or the ways the atmosphere has transformed over time.

Conversely, studying other planets could reveal more about Earth and how it came to sustain life. Other planets might also serve as cautionary tales: “Exploring space allows us to gather the knowledge to save ourselves from asteroids, from pollution, and from using up the limited resources on Earth,” Kaltenegger writes.

But in her view, the best way for humans to save themselves long term isn’t necessarily to fend off planetary troubles. It’s to get out of here. All planets — alien or not, polluted or not — will someday be rendered uninhabitable: The stars they orbit will go out “in a hot blaze of glory,” boiling life out of existence, or they will slowly get dimmer and their worlds slowly colder. Though this won’t happen to Earth for billions of years, if you would prefer neither, Kaltenegger has a suggestion: “Let’s become wanderers of this amazing universe,” she writes. “It does not have to end in fire or ice.”

Sarah Scoles is a science journalist based in Colorado, and a senior contributor to Undark. She is the author of “Making Contact,” “They Are Already Here,” and “Countdown: The Blinding Future of 21st Century Nuclear Weapons.”

Researchers advance detection of gravitational waves to study collisions of neutron stars and black holes

Alerts can now be sent less than 30 seconds after detection.

IMAGE:

THE GRAPH SHOWS THE AMOUNT OF TIME IT TAKES RESEARCHERS TO SEND OUT AN ALERT, ON AVERAGE THE ALERT TIME IS UNDER 30 SECONDS.

view moreCREDIT: ANDREW TOIVONEN

MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL (04/26/2024) — Researchers at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities College of Science and Engineering co-led a new study by an international team that will improve the detection of gravitational waves—ripples in space and time.

The research aims to send alerts to astronomers and astrophysicists within 30 seconds after the detection, helping to improve the understanding of neutron stars and black holes and how heavy elements, including gold and uranium, are produced.

The findings were recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), a peer-reviewed, open access, scientific journal.

Gravitational waves interact with spacetime by compressing it in one direction while stretching it in the perpendicular direction. That is why current state-of-the-art gravitational wave detectors are L-shaped and measure the relative lengths of the laser using interferometry, a measurement method which looks at the interference patterns produced by the combination of two light sources. Detecting gravitational waves requires measuring the length of the laser to precise measurements: equivalent to measuring the distance to the nearest star, around four light years away, down to the width of a human hair.

This research is part of the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA (LVK) Collaboration, a network of gravitational wave interferometers across the world.

In the latest simulation campaign, data was used from previous observation periods and simulated gravitational wave signals were added to show the performance of the software and equipment upgrades. The software can detect the shape of signals, track how the signal behaves, and estimate what masses are included in the event, like neutron stars or black holes. Neutron stars are the smallest, most dense stars known to exist and are formed when massive stars explode in supernovas.

Once this software detects a gravitational wave signal, it sends out alerts to subscribers, which usually include astronomers or astrophysicists, to communicate where the signal was located in the sky. With the upgrades in this observing period, scientists are able to send alerts faster, under 30 seconds, after the detection of a gravitational wave.

“With this software, we can detect the gravitational wave from neutron star collisions that is normally too faint to see unless we know exactly where to look,” said Andrew Toivonen, a Ph.D. student in the University of Minnesota Twin Cities School of Physics and Astronomy. “Detecting the gravitational waves first will help locate the collision and help astronomers and astrophysicists to complete further research.”

Astronomers and astrophysicists could use this information to understand how neutron stars behave, study nuclear reactions between neutron stars and black holes colliding, and how heavy elements, including gold and uranium, are produced.

This is the fourth observing run using the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), and it will observe through February 2025. In between the last three observing periods, scientists have made improvements to the detection of signals. After this observing run ends, researchers will continue to look at the data and make further improvements with the goal of sending out alerts even faster.

The multi-institutional paper included Michael Coughlin, Assistant Professor for the School of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Minnesota in addition to Toivonen.

LIGO is funded by the National Science Foundation, and operated by Caltech and MIT. More than 1,200 scientists and some 100 institutions from around the world participate in the effort through the LIGO Scientific Collaboration.

To read the entire research paper titled, “Low-latency gravitational wave alert products and their performance at the time of the fourth LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA observing run”, visit the PNAS website.

JOURNAL

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

ARTICLE TITLE

Low-latency gravitational wave alert products and their performance at the time of the fourth LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA observing run

ARTICLE PUBLICATION DATE

23-Apr-2024