Why Washington Targets Iran and Venezuela

Empire, Energy, and Ideology

Venezuela and Iran hold the largest and third-largest petroleum reserves in the world, respectively. Both have also been targeted for regime change by Washington. The two commonalities are not unrelated.

Of course, the world’s hegemon would like to get its hands on all their oil. But it would be simplistic to think that would be only for narrow economic reasons. Control over energy flows – especially from countries with large reserves – is central to maintaining global influence. Washington requires control of strategic resources to maintain its position as the global hegemon, guided by its official policy of “full spectrum dominance.”

For Venezuela and Iran, sovereign control of vast hydrocarbon assets is a precondition for exercising a modest level of independence and even some regional and global influence in a geopolitical landscape dominated by the US and its allies. But their drive for self-determination is animated by a third and essential shared characteristic. That is, the political one; both are led by revolutionary administrations.

The Bolivarian Revolution in Venezuela and the Islamic Revolution in Iran were both of necessity anti-imperialist. And it for this political reason, even more than the economic, both have earned Washington’s hostility. Conversely, the Iran-Venezuela political relationship is rooted in mutual support against US aggression and a commitment to sovereignty and non-interference.

Venezuela-Iran relations

Venezuela has been at the forefront of Iran’s engagement in Latin America. The two nations were founding members of the OPEC alliance of oil-producing countries in 1960.

Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez made his first visit to Iran in 2001. Since then the two countries have forged close relations, especially regarding energy production, industrial cooperation, and economic development. Chávez awarded visiting Iranian President Mohammad Khatami with the Order of the Liberator, praising him as an anti-imperialist. Venezuela and Iran “are firm in the face of any aggression,” said Chávez.

With Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s election as Iran’s president in 2005, he and Chavez visited each other multiple times forming a self-described “axis of unity” against US imperialism. Hundreds of bilateral agreements were executed between the two oil-producing states. Chavez supported Iran’s nuclear program, pledging in 2006 to “stay by Iran at any time and under any condition,”

In a prescient address at Tehran University, Chávez admonished: “If the US empire succeeds in consolidating its dominance, then humankind has no future. Therefore, we have to save humankind and put an end to the US empire.” With the passing of Chávez and the election of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela-Iran relations continued to consolidate.

In 2015, US President Barack Obama declared Venezuela an “extraordinary threat” to US national security as an excuse to impose unilateral coercive measures on Caracas. By 2017, US President Donald Trump intensified the hybrid war against Venezuela with a “maximum pressure” campaign.

Amid crippling US sanctions, Iran dispatched multiple tanker shipments in 2020 to help stabilize Venezuela’s fuel supply. Iran, along with China, also sent technicians to help repair refineries. It is no exaggeration to say that Iran’s assistance was been a lifeline for Venezuela.

Joint projects have included ammunition plants, auto assembly (Venirauto), a cement factory, the Venirán Tractor Factory, and refinery upgrades. An Iranian supermarket chain even opened stores in Venezuela.

Then Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi signed a 20-year cooperative agreement with Venezuela in 2020. Besides tourism, food production, and opening airplane routes, the agreement addressed mutual defense, including the continued transfer of drone-making technology. Raisi complemented Caracas for “exemplary resistance against sanctions and threats from enemies and imperialists.”

In 2022, agreements were signed to restore Venezuela’s El Palito refinery and explore nanotech collaboration. This year, the two countries established a fiber optic factory. Plus, there have been extensive cultural and educational exchanges.

In Washington’s crosshairs

The refusal of Venezuela and Iran to align with the US geopolitical agenda is a key factor in Washington’s coercive strategy. It reflects the hegemon’s broader pattern of targeting resource-rich, independent states that resist integration into its “world order.”

Both countries have rejected Western dominance and have nationalized their considerable oil sectors. Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh established NIOC in Iran in 1951, precipitating the CIA/M16 coup that disposed him. Venezuelan President Carlos Andrés Pérez established PDVSA in 1976, later expanded and reoriented by President Chávez after 2002.

Current US sanctions on Iran and Venezuela reduce their ability of to sell oil freely. This limits alternative energy markets that could compete with US-aligned suppliers such as the Gulf states. It also reduces petrodollar diversification. Both countries have tried to trade oil outside the dollar system, including via a system of barter with allies.

Moreover, Venezuela and Iran have been targeted for their non-aligned foreign policy. Central has been Iran’s pivotal position in the resistance to Zionism. Iran supports Hezbollah, the former government in Syria, Ansar Allah (Houthis), and above all the Palestinian struggle. Likewise, Venezuela has been among the foremost supporters in Latin America of the Palestinian’s right to self-determination, having severed relations with Israel in 2009. Caracas has also opposed US-backed regional blocs and supports socialist and anti-neoliberal movements (e.g., ALBA, ties with Cuba and Nicaragua).

Confronted by aggressive hostility by the US and its allies, both Iran and Venezuela have pivoted toward China, Russia, and the BRICS+ coalition as alternatives. Sanctions from the US and its partners have accelerated the creation of alternative financial, logistical, and diplomatic systems that bypass Washington’s control (e.g., INSTEX, barter, crypto, regional banks).

In a recent interview, Iranian diplomat Ali Faramarzi affirmed that Venezuela and Iran are bound by profound affinities. They have significantly deepened what TeleSUR calls their “symbiotic” relationship, forging an alliance that spans political solidarity, economic cooperation, military collaboration, and shared ideological stances. Both nations, facing intense pressure and sanctions from the US, have found common cause in resisting Western hegemony and promoting a multipolar world order.

Regime change in Iran could have major negative consequences for Venezuela. Reestablishment of a US client-state, as it was under the Shah of Iran, would mean the loss of diplomatic support for Caracas, the probable end to energy cooperation, greater defense vulnerabilities, and cascading adverse economic and trade repercussions.

Marea Socialista: Against bureaucratic authoritarianism and capitalist exploitation in Venezuela

First published in Spanish at Aporrea. Translation by Anderson Bean published in Tempest along with introductory note.

Tempest is publishing the following English translation of a statement issued by the Venezuelan socialist organization Marea Socialista. A longstanding anti-capitalist and anti-bureaucratic current within the Venezuelan Left, Marea Socialista emerged from the revolutionary process begun under Chávez but broke with the ruling party as it shifted toward authoritarianism and neoliberalism.

The statement offers a powerful critique of the Maduro government and its increasing authoritarianism, as well as the complicity of both traditional right-wing opposition forces and international actors. At the same time, Marea Socialista puts forward an urgent call for rebuilding working-class organization and political independence in Venezuela, situating their struggle within a broader internationalist and anti-capitalist framework.

This statement was originally published in Spanish in Aporrea on May 21 and reflects the perspective of a left force in Venezuela that rejects both the repression of the Maduro regime and the neoliberal alternatives promoted by the traditional opposition. Tempest presents this translation in the spirit of international solidarity and to help amplify the voices of those resisting authoritarianism and exploitation from below. Minor translation edits have been made for clarity.

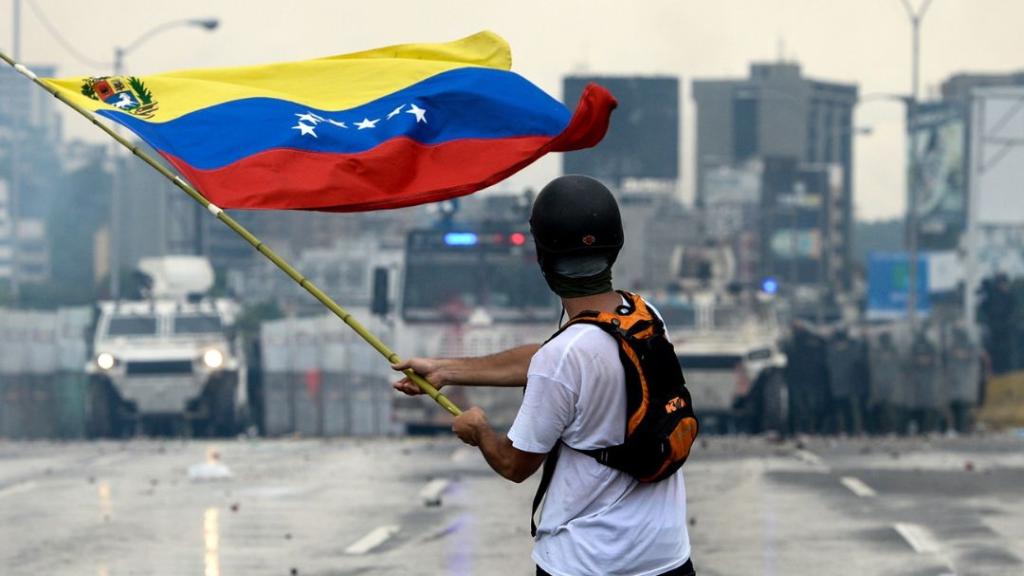

The first months of the year in Venezuela have been and continue to be marked by several key issues, such as Trump’s sanctions, announcements of constitutional reform, the economic emergency decree, the deportation and imprisonment of Venezuelan migrants in El Salvador at the behest of the U.S., continued political detentions and criminalization of activism under Maduro, forced disappearances, the continuation of the “zero wage” policy for the working class, and the regional and legislative elections scheduled for the end of May. Also significant are the diverging strategies among factions of the right-wing opposition.

The phase opened on January 10 and its international framework

In previous statements, we noted that Venezuela had already fully entered into a de facto government. Maduro’s swearing-in occurred without proper electoral records from the National Electoral Council (CNE), meaning the regime is upheld by repression from the military-police apparatus, authoritarian control by a bureaucratic caste, and state management for the benefit of a corrupt, lumpen-bourgeois elite. All of this took place in a geopolitical environment characterized by Trump’s hostility toward Venezuela. After an apparent initial “flirting,” the US tightened its pressure and Venezuela returned to prioritizing alliances with China and Russia. However, Venezuela has not been truly able to escape the conditions imposed on the production and sale of its oil by the United States. Despite Venezuela’s nationalist rhetoric, actual sovereignty has been lost, worsened both by sanctions and by the regime’s own destruction of the productive apparatus and national treasury.

The policy of the Maduro-Military-PSUV (United Socialist Party of Venezuela) government prolongs the worst aspects of the period opened by the economic sanctions. The US withdrawal of licenses for doing of business with Venezuela affects not only Chevron — which was being positioned to replace PDVSA (Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A., the state-owned oil and gas company of Venezuela) amid the collapse of the “corruptocracy” — but also undermines Venezuela’s trade relations with other nations and companies, once again triggering a drastic drop in national income and worsening the hardships faced by the Venezuelan people. Maduro uses these sanctions to justify repressive anti-worker measures.

Trump not only attacks Venezuelan migrants who hoped to improve their lives by living and working in the U.S. due to the unlivable conditions in Venezuela, but also makes life even harder for the Venezuelan people back home. We reject these sanctions, which primarily harm the population and serve as an economic and political excuse for the government’s authoritarian and anti-worker practices.

The government’s lack of transparency and its arbitrary handling of resources, revenue, and their distribution make it difficult to clearly determine how much damage is due to the economic sanctions and how much is the government’s own responsibility. However, in a country that has already suffered massive embezzlement — greater than its foreign debt and occurring even before the sanctions — it is clear that the sanctions have only intensified and worsened harm that was already being done to the population.

Subservience and right-wing complicity with Trump’s attacks on Venezuela

In this regard, we denounce the complicity of right-wing and pro-imperialist opposition sectors, such as those led by María Corina Machado, who are calling for and supporting sanctions that are more harmful to the Venezuelan people than to the government itself. In exchange for overthrowing Maduro, they offer to hand the country over to the United States and transnational corporations, and to continue the worst exploitation of ultra-cheap labor we have ever known. In this last point, they hardly differ from Maduro; only that Machado aligns with the US and is a groveling ally of Trump, while Maduro pragmatically relies on whoever serves him best to stay in power and sides with Washington’s competitors. But both, Maduro and Machado, represent two modalities of Venezuelan capitalism and two sectors vying for power against the interests of the working class.

A sector of the bourgeoisie adapts to and benefits from Maduro’s policies

There are, however, other sectors of the ruling class and their politicians, who, seeing no prospects for Maduro’s departure, are accommodating themselves by seeking some benefit or opting for coexistence with the regime to endure and wait for a more favorable time. They are trying to survive politically (and economically) and gain some ground, such as the Rosales and Capriles, and others of their ilk, by taking advantage of the electoral loopholes that will allow them to reappear after the latest government fraud in the presidential elections of July 2024.

The obstacles of the flawed electoral system and repression

In those last elections, Marea Socialista (with other leftist organizations) called for null votes because it was impossible to run candidates who represented working class and popular interests due to electoral obstacles, bans and disqualifications. We did not do this because we are abstentionist by principle, despite the difficulties, we have tried to participate in elections in the past without renouncing the vote. We have always sought to use even the narrowest democratic margins to bring our politics to the heart of the people. But, for us, participation in elections is a tool to advance the workers’ and popular struggle with anti-capitalist objectives and to defend the rights of the exploited.

Marea Socialista and other leftist organizations opposed to this corrupt, counterrevolutionary, and authoritarian government have been obstructed, impeded, or arbitrarily prohibited from participating in elections with their own candidates. The government, the National Electoral Council (CNE) and the Supreme Court (TSJ) readily authorize political parties that negotiate with Maduro, but they exclude and trample on the left that confronts him and denounces his poor parody of “socialism,” the usurpation of revolutionary banners, and the imposition of a form of capitalism even more brutal than that known in the past.

In response to this, there have been — and still are — some sectors of the anti-Maduro left that choose to support bourgeois candidates, supposedly in order to pave the way for “Maduro’s departure.” Unfortunately, this approach ends up strengthening the very forces that exploit the people and abandons the struggle for independent, working-class goals. Instead of building class consciousness, organizing autonomously, and mobilizing from below, these groups align themselves with the political representatives of wealthy business interests or affluent bureaucrats — both of whom act against the interests of the working class.

For all these reasons, and even more so after the events surrounding the the July 2024 elections and the unilateral self-proclamation in January 2025, we reaffirm that there are no electoral or democratic guarantees, nor are there any candidates worthy of our votes among those who can (or are allowed to) run under the current situation. We are not excluding ourselves voluntarily; rather, we have been forcibly excluded from electoral participation due to the complete absence of guarantees to exercise this right, as well as the lack of respect for democratic norms, and the will of the electorate.

They left us no alternative but electoral abstention — but for us, this does not mean withdrawing from politics. On the contrary, it means channeling all our efforts into organizing, denouncing injustice, political education, and defending rights in every social and public space. Our goal is to help build an independent social and political force rooted in the working class and the people — free from the political leaderships mentioned above, from the government bureaucracy, and from capitalist sectors who, even if they claim to “oppose” the government, benefit from or exploit its anti-worker policies. These sectors are complicit in maintaining the most miserable wages seen in the country in decades — even by the standards of the most impoverished nations in Latin America and the world.

Our fundamental task is to resist and rebuild the social and political strength of the working class

Our central task is rebuilding autonomous organizations of workers and popular sectors, strengthening their capacity for mobilization around their own agenda — rather than the one imposed by the government or the political opposition of the business class. In this regard, we have joined efforts like the National Meeting for the Defense of People’s Rights, alongside the Communist Party of Venezuela (PCV-Dignidad), the historic leadership of Patria Para Todos (PPT-APR), the Party of Socialism and Freedom (PSL), and Communist Revolution. We also regularly coordinate joint actions with the Socialist Workers League (LTS), with various unions and labor movements, feminist groups, and committees demanding freedom for political prisoners. By developing this kind of social and political force, we will be better positioned to keep moving forward to continue fighting for democratic, economic, and social rights, and to bring closer the horizon of political change that empowers the working class and allows us to win better living conditions — on the path toward a government of workers and the people, one that wrests control from the bureaucracy and capital and drives the transformations needed in favor of the vast majority.

The fight for wages is central to improving living conditions and promoting mobilization

Right now, our top priority is the fight to defend wages against the starvation-level and semi-slavery pay imposed by the Maduro–military–PSUV government and the business elite, who have repeatedly violated the Constitution by enforcing what we call a “zero wage” policy. For years, the minimum wage has remained stagnant and currently sits below two US dollars a month — sometimes even less, due to the ongoing collapse of the bolívar. Meanwhile, the cost of a basic food basket1 exceeds $500, and the full basic basket2 is over $1,000. This clearly violates Article 91 of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela’s Constitution, which states that the minimum wage must be based on the cost of the basic basket. And if there is no wage, all other rights are lost or severely undermined.

We reject the adaptation of union bureaucracies to the agenda of corporate interests, which simply aims to convert government-paid bonuses into formal wages and set the minimum wage at just $200. But that’s far below what people need to live — less than half the cost of the food basket (just food), and less than 10 percent of the full basic basket (which includes housing, transportation, education, health, etc.).

We also reject the common excuses that sanctions prevent higher wages, or that the economy must grow first, or that higher wages are simply not “realistic” or “possible,” especially since those same officials never sacrifice the profits they earn through corruption, nor does it sacrifice the profits businesses earn by squeezing nearly all wages into surplus value since wages don’t even cover the cost of getting to work.

The myth that raising wages causes inflation has long been debunked, as we have endured hyperinflation for years while wages have remained frozen. The looting of the country has been so extreme that any real “economic recovery” would have to begin with the expropriation of all those who have been robbing us in one way or another through dirty dealings and corruption.

We welcome any step that moves toward restoring the constitutionally guaranteed minimum wage, but only as a step in the larger fight to secure what is our legal right — one that is non-negotiable and should not be undermined by the constitutional reform the government now seeks, aimed at eliminating Article 91, the very article they have blatantly violated.

Constitutional reform to “legitimize” its own violations of rights

The unconstitutional reform and the state of economic emergency decree serve no other purpose than to undermine our rights and give a veneer of legitimacy to the violations that have already been committed and those still to come — disguising everything in the misleading language typical of the leaders of the PSUV and the government. We demand: No rollbacks on the rights formally won under the 1999 Constitution!

We have no doubt that this reform would pave the way for greater authoritarianism and repression, and more discretion in the corrupt or elitist handling of national resources.

Reclaiming class organization and political independence

Let us reclaim our organization, our union, and political independence and democratically forge our own agenda for struggle without subordinating it to the bureaucracy or to capital. Let us reclaim union democracy, coordinate our struggles, and practice solidarity among workers as a path to recovering our identity and strength. Through the patient and gradual reconstruction of the working-class social fabric, let us prepare ourselves to help catalyze and channel the uprising of the people in defense of their freedom and justice.

Let us not follow those who tell us to obey the ruling bureaucracy or the millionaire owners of major corporations, transnationals, and their revolving candidates. We call on the people who oppose Maduro to break with those in Venezuela who serve Trump’s agenda and who tighten the noose of misery around Venezuelan workers and the broader population. We call for a break with those who today show not the slightest concern for the Venezuelans who were forced to migrate due to this disastrous government — and yet support the US president who deports them as if they were criminals and sends them to prison camps for “terrorists” in El Salvador (as we’ve already denounced in a previous statement). We are speaking, among others, about the positions taken by María Corina Machado and Edmundo González.

The issue of Venezuelan migration

We therefore denounce María Corina Machado for being an accomplice to Trump in his measures against Venezuelan migrants, just as we denounce Trump and Bukele for practicing forced disappearances, human trafficking, kidnapping, and legally imprisoning innocent people in prisons, without due process and with total disregard for human rights, maintaining a slave regime in prisons and commercializing the judicial-prison system.

Maduro, for his part, does something similar with Venezuela’s judicial system, police forces, and prisons, using them to persecute and imprison political opponents, dissenters, and social activists. The very abuses Maduro criticizes Trump and Bukele for, his own government commits in Venezuela, violating democratic and human rights.

We welcome the social mobilizations in defense of immigrants in the United States, not just out of solidarity, but also as essential to combating the authoritarian and fascist threat emerging in that country, one that endangers the entire world, seeks to dismantle hard-won rights, and which is complicit in the genocide in Gaza and the attacks on civilians in Yemen, among other crimes.

The alternative we need

We need an anti-capitalist, anti-bureaucratic, and internationalist alternative, because the current situation cannot be resolved by repackaging the same failed model. Any real solution must connect with the struggles of the working class and oppressed people internationally. This is not a crisis that can be solved within the borders of a single country — it demands global resistance against the dominant powers that exploit and oppress us. That is why we aim to strengthen both Marea Socialista and maintain its ties with the international organization of revolutionary parties, the International Socialist League (ISL), a global network of revolutionary parties. That is why we also want to strengthen the Venezuelan opposition left and advocate for abandoning the positions of left-wing sectors that, pretending to bet on a false “lesser evil,” support the right in an attempt to “get rid of Maduro by any means necessary.”

The path is one of class consciousness and political independence — organizing and mobilizing around our own struggles, building the political tools we need, and forging alliances from below to overcome bureaucratic authoritarianism and capitalist exploitation in Venezuela.

- 1

The canasta alimentaria, or the food basket, includes only essential items needed to meet the minimum nutritional requirements for a family, typically of five people, over a month. It reflects the cost of basic subsistence and is tracked monthly by organizations like the Centro de Documentación y Análisis Social de la Federación Venezolana de Maestros (CENDAS-FVM). Items include staples like rice, flour, meat, milk, eggs, beans, pasta, oil, vegetables, and others.

- 2

The canasta básica, or the basic basket, includes the food basket plus other essential goods and services, such as housing (rent, maintenance), health care, education, transportation, clothing, personal hygiene products, household cleaning supplies. It reflects the total monthly cost of living for a typical family to maintain a minimally decent standard of living.

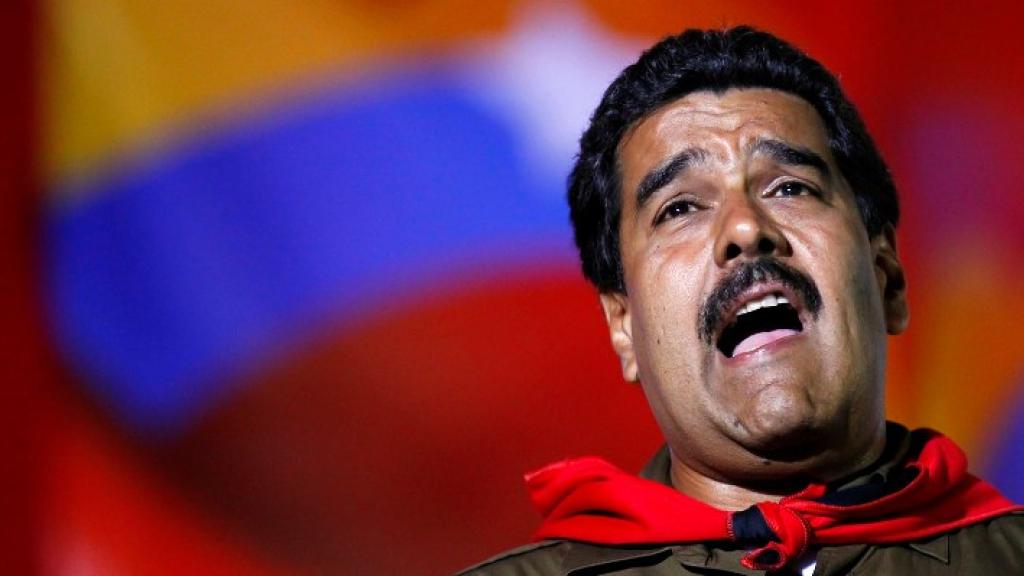

Demonising Nicolás Maduro: Fallacies and consequences

Criticism of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro from a leftist perspective is absolutely necessary. Some of it comes from those who, to varying degrees, support his government. Emiliano Teran Mantovani and Gabriel Hetland — who recently criticised my position on Maduro — and I are in agreement on the importance of such critical analysis.

However, in spite of this common denominator, there are fundamental differences between us with regard to my insistence on the need to contextualise the errors committed by Maduro and go beyond a simplistic binary of uncritical support for Maduro versus demonisation.

These issues have far-reaching implications. The failure to objectively contextualise errors, transcend binaries and recognise shades of differences translates into an underestimation of the gravity of US sanctions and the denial of positive aspects of the Maduro government. These positions and shortcomings seriously undermine international solidarity work and anti-imperialism in general.

Centring the US war on Venezuela

Teran begins his article stating, “I want to make my position clear … these sanctions are entirely condemnable,” a position that he acknowledges is “universally shared” on the Venezuelan left and even by “some liberal scholars, intellectuals and opposition figures.” His pronouncement, however, glosses over one of my main points. It is misleading to say “I am opposed to the sanctions” and then proceed to attack government policy as if they are two separate topics.

My article explains in detail why the war on Venezuela needs to be placed at the centre of any serious analysis of the Maduro presidencies. The Washington-orchestrated war on Venezuela extends well beyond sanctions since it encompasses a broad array of regime-change and destabilisation actions. Yet Teran, like Hetland, limits his references regarding Washington machinations to the sanctions.

To make matters worse, Teran, in effect, downplays the severity of the sanctions, claiming they “do not explain the root causes” of the nation’s crisis. For Teran, the sanctions only had a “subsequent negative impact” — subsequent, that is, to the allegedly grievous errors committed by Maduro, and Chávez before him.

One example of Teran’s underestimation of the effects of the sanctions is his statement: “Ellner refers to the sanctions imposed by the Barack Obama administration in 2015, but those were limited to freezing assets and bank accounts in the US…” Teran portrays Obama’s executive order as an innocuous, symbolic measure. It hardly was.

As I noted, Obama’s order, which declared Venezuela “an unusual and extraordinary threat” to US national security, “signaled an escalation of hostility from Washington.” Even Hetland, writing a few years back, points out that Obama “pressured American and European banks to avoid business with Venezuela, starving Venezuela of needed funds.” It is not difficult to grasp why US companies operating factories in Venezuela disinvested in response to the president of their country calling Venezuela a threat to US national security.

As I previously wrote, “Obama’s executive order sent a signal to the private sector. After the order was implemented, various large U.S. firms including Ford and Kimberly Clark closed factories and pulled out of Venezuela.” They were soon followed by General Motors, Goodyear, and Kellogg’s, as well as Japanese firm Bridgestone.

Indeed, even before Donald Trump assumed the presidency in 2017, a de facto financial embargo had already been imposed on Venezuela. Opposition spokesperson and economist Francisco Rodríguez noted back then that “the financial markets are closed to Venezuela.”

Teran’s minimisation of the effects of the war on Venezuela reinforces and legitimises the opposition’s narrative, which ridicules Maduro’s assertion that Washington’s actions are responsible for Venezuela’s dire economic situation. Moisés Naím, one of the architects of Venezuela’s neoliberal policies of the 1990s, for example, writes: “Blaming the CIA … or dark international forces, as Maduro and his allies customarily do, has become fodder for parodies flooding YouTube.”

Similarly, Teran says: “Followers and supporters of Maduro’s government seem to always prefer to look for external scapegoats.” In my article, I cite specific examples of the abundant, well-documented literature that substantiates Maduro’s allegations regarding generously financed “dark international forces.”

In his effort to discard the relevance of the war on Venezuela, Teran even suggests that explanations of Maduro’s implementation of neoliberal policies on the basis of US imperialist aggression are akin to those put forward by those who seek to justify Netanyahu’s genocide against Palestinians on the basis of Hamas’ October 7 attack.

But it should seem pretty obvious to anyone on the left that drawing an equivalence between US imperialism and the October 7 attack is somewhat far fetched, and that placing Maduro’s economic policies in the same category as Netanyahu’s genocide is even more outrageous.

Neither praise nor condemnation

Turning to the second area of contention, serious analysis of Maduro needs to avoid absolutes with regard to either praise or condemnation of his government. Failing to grasp the complexity of how a progressive government is forced to navigate a situation imposed by the world’s most powerful nation located in the same hemisphere, leads to simplistic conclusions that often align with those of the political right.

Teran accuses me of being one-sided. He claims my “arguments lack nuance” and that I fail to “avoid simplistic binaries.” In doing so, he overlooks the criticisms of Maduro that I presented in my article and have analysed in greater detail in other publications.

Accusing me of one-sidedness mirrors what others who vilify Maduro do when they brand supporters of progressive Latin American governments as “campist,” or upholding “a Manichaean outlook” – a phrase used by Teran. Both terms are reminiscent of McCarthyism, with its attack on the entire left for being crypto-Communists or fellow travelers.

By failing to recognise the validity of the position of critical support for Maduro, Teran shows he is on board with a polarisation of Venezuelan politics that leaves gradations out of the picture. For example, Teran (like Hetland) unfairly accuses me of justifying repression by omission, adding that after the July 28, 2024 presidential elections, “sectors of the international left” ended up “legitimising the brutal repression.”

He neglects to mention that I suggested the evidence of significant right-wing and foreign involvement in the post-July 28 violent protests does not rule out the possible use of excessive force by the Venezuelan state, as the two are not “mutually exclusive”.

Which left?

Teran ends by asking why, instead of providing critical support to Maduro, does the international left not “dedicate their energy, resources, support and advocacy to strengthening a left-wing opposition [in Venezuela] that might someday challenge for political power?” The question, however, is somewhat ambiguous.

If Teran is referring to what political scientists call “a loyal opposition” — one that recognises the challenges facing Maduro, does not hesitate to support him in his denunciation of imperialist aggression, and avoids equating him with the Venezuelan far right — then such a proposition sounds reasonable.

But the bulk of the Venezuelan left opposition hardly fits this description. It demonises Maduro, just as Teran and Hetland do, and the actions of many of these leftists play into the hands of the political right.

If Maduro is brought down, the far right — headed by María Corina Machado, who says she wants to see Maduro and his family behind bars — will undoubtedly dominate the new regime, with Washington’s blessing. If this were to happen, the most likely scenario would be the kind of brutal repression that has historically followed the downfall of progressive governments, from Indonesia in 1967 to Chile in 1973. The anti-Maduro left is simply too weak to shape the course of such events.

It is troubling, for instance, that the Communist Party of Venezuela (PCV), in spite of its glorious history dating back to its founding in 1931, endorsed the presidential candidacy of Enrique Márquez in last year’s election. Márquez was a prominent leader of one of the main parties that actively promoted destabilisation and regime change in the protracted street protests against Maduro in 2014 and 2017, and wholeheartedly supported the right-wing parallel government of Juan Guaidó after 2019.

International solidarity

Two key implications of the debate over the demonisation of Maduro hold particular significance for the solidarity movement. First, vilifying Maduro discourages solidarity work. I have reached this conclusion based on my experience giving numerous talks sponsored by solidarity groups in cities throughout the US and Canada since 2018.

Solidarity activists have made clear to me that a fairly favourable view of the Maduro government — specific criticisms notwithstanding — is a motivating force for them. By contrast, those who despise a government are unlikely to work with the same degree of enthusiasm in opposition to US interventionism.

In this respect, the solidarity movement differs from the anti-war movement, which tends to be less focused on the domestic politics of the nations of the South and more concerned with military spending and the death of US soldiers, in addition to the devastation caused by US armed intervention.

Secondly, an analysis that contextualises government errors and the erosion of democratic norms leads to a fundamental conclusion. The extent to which the war on Venezuela is relaxed directly correlates with the potential to deepen democracy, invigorate social movements and expand the government’s room for maneuver, thereby increasing the likelihood of overcoming errors.

History, after all, teaches us that war and democracy are inherently incompatible. In their vilification of the Maduro government, Hetland and Teran overlook this simple truth.

.jpg)