CRT

The Rediscovery Of America From Within – Book Review

The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of US History,

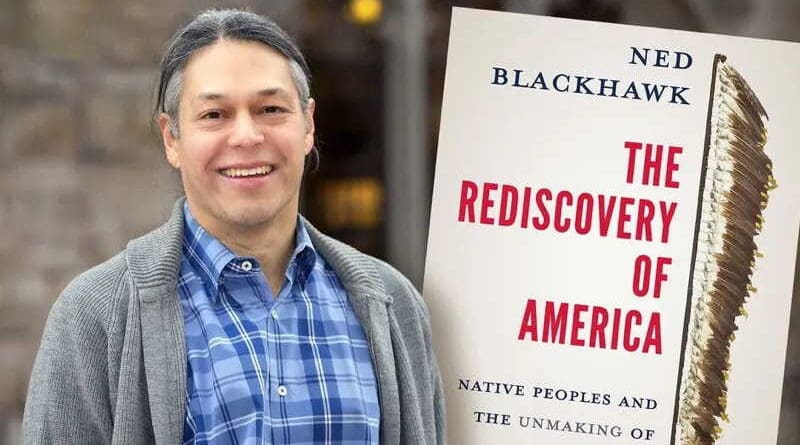

Ned Blackhawk and "The Rediscovery of America

By Jan Servaes

In 2019, The New York Times published “The 1619 Project” by Nikole Hannah-Jones. Four centuries after African captives arrived on the Virginia coast, this project reshaped America’s origin story, centering on slavery and the contributions of African Americans. An updated version appeared in 2021 and was summarized in a review as “Decentering Whiteness and Uplifting Black Voices.”

It was a long-awaited correction to white, Eurocentric narratives that still dominate. This new narrative questions concepts like discovery (by Columbus) and colonization (by Europeans) and places Indigenous peoples at the center of American history. The list of First Nation History analyses has since grown considerably. Along with Kathleen DuVal, history professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and recent Pulitzer Prize winner, Ned Blackhawk’s “The Rediscovery of America” serves as a central piece in these kinds of overviews.

Ned Blackhawk, a member of the Te-Moak tribe of the Western Shoshone in Nevada —a board member of the School for Advanced Research, the Howard R. Lamar Professor of History and American Studies at Yale University, and winner of numerous professional awards for his research on the influence of Indigenous peoples on and in the formation of the United States— asks, “How can a nation founded on the homelands of dispossessed Indigenous peoples be the most exemplary democracy in the world?” (p. 1). This opening question hangs over the book like a specter, a ubiquitous reminder of the centuries-long struggle for land and resources by Native Americans.

And how have historians ignored the central role of Indigenous peoples in American history? In this, Blackhawk belongs to a new generation of historians who no longer view America and its history from a Eurocentric perspective, but instead recognize the influence of the countless Indigenous peoples. And the impact was significant, for by 1492, the date Columbus officially “discovered” the Americas, it was already home to 75 million indigenous peoples (p. 19). (Other estimates range from 8 to 142 million, with the majority around 40 million.)

“The Rediscovery of America,” as a synthesis, aligns with other research and uses primary sources on seminal events in American history to emphasize the involvement of indigenous peoples in those events. Indigenous peoples have always played a central role in American history, Blackhawk argues, but scholars of American history have often ignored the significance of indigenous peoples in shaping American history.

The book also debunks the myth that indigenous peoples were quickly overrun by superior European colonists. Indigenous peoples were able to retain most of their territory in the United States until the 19th century. In the early 19th century, following the American Revolution and a more robust westward expansion of white settlers with financial and military support from the federal government, most Indigenous peoples were dispossessed of their lands and driven westward.

Blackhawk thus debunks common mythologies about American history and Indigenous peoples. Events considered fundamental often revolve around war and violent confrontations between settlers and Indigenous peoples.

‘Another’ History

To tell this “other” history of the United States, Blackhawk rejects narratives of discovery and emphasizes a long history of encounters between Indigenous peoples and newcomers in North America, as well as the influence and mobility of Indigenous peoples.

He describes some of the interactions between Indigenous peoples and Europeans that shaped the development of the United States. Each tribe, of course, has its own history, and Blackhawk necessarily selects a part of this complex history. A key theme is how Indigenous peoples forced colonists to recognize and respect the sovereign rights of Indigenous peoples.

Thus, Ned Blackhawk weaves together five centuries of Indigenous and non-Indigenous history, from Spanish colonial exploration to the rise of Native American self-determination in the late twentieth century. Native Americans played a fundamental role in shaping American constitutional democracy, he argues, even as they were murdered and dispossessed of their lands.

The various layers of influence and interaction aren’t always what we learned in school, but Blackhawk aims to make the gaps in that history of the United States more coherent. He advocates for a paradigm of “encounter” rather than “discovery,” in which Europeans and their colonist communities are not the exclusive subjects of study. He points to a generation of scholars who have demonstrated that “American Indians were central to every century of American historical development,” particularly during the era of the American Revolution.

In this transformative synthesis, he demonstrates that

• European colonization in the 17th century was never a predetermined success;

• Indigenous peoples helped shape the crisis of the English empire;

• the initial impetus for the American Revolution was provided by Indian affairs in the interior;

• the common myths about relations between Indigenous people and colonists, such as the myth of Thanksgiving, were often based on peaceful coexistence, from which cultural influences (and even intermarriage) arose;

*California Native Americans targeted by federally funded militias were among the first casualties of the Civil War;

• The Union victory led to a definitive reassessment of Native communities in the West; and

• Twentieth-century reservation activists reshaped American law and politics.

Structure

The book is divided into two parts, each containing six chapters.

Part I, aptly titled “Indians and Empires,” outlines the history of encounters between Indigenous peoples and the Spanish in the southern borderlands, moves to the Northeast and the rise of British North America, and highlights the development of New France.

The second half of Part I examines the struggle for the heart of the continent, focuses on the Indigenous origins of the American Revolution, and concludes with the creation of federal Indian policy in the aftermath of the Revolution.

Part II, “Struggles for Sovereignty,” begins with the dispossession of Indigenous peoples in the early years of the republic, jumps to the West Coast to outline the region’s role in the Monroe Doctrine, and connects the Civil War with what Blackhawk calls “the Indigenous West.”

The final three chapters focus on the reservation era (specifically, the seizure of both Indigenous lands and Indigenous children), the rise of Indigenous activism in the early twentieth century, and, finally, Indigenous resistance to the severance policy and the push for self-determination.

Blackhawk moves easily across time and space, connecting crucial events in Indigenous history with broader themes and events in American history. While he doesn’t shy away from describing the violent ways in which Indigenous peoples were torn from their homelands, these descriptions are never gratuitous—instead, Blackhawk details the deliberate processes by which the US government sought to dispossess Indigenous peoples and disenfranchise them. “While violence was an essential component of colonialism, it was never sufficient to achieve permanent goals for the empire,” Blackhawk argues (p. 81).

The Rediscovery of America is therefore not intended to be a sensational account of Native American history, one that describes the wars, massacres, and outbreaks that devastated indigenous peoples. But Blackhawk convincingly argues that identifying American history as a history of genocide complicates the prevailing, rather “Eurocentric” narrative, and the book aims to clarify these contested meanings.

The Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) between Great Britain and France

Consider, for example, the Seven Years’ War between Great Britain and France, which began as a dispute over North American land claims in the region around Pittsburgh and ended in 1763 when France ceded Canada to Great Britain.

Under the leadership of Pontiac, a chief from Odawa (Ottawa), the Native Americans took up arms against the British in what became known as Pontiac’s Rebellion. A conflict ensued that would inflame tensions between the British Crown and its own subjects and herald the demise of the British Empire in North America.

The movement of settlers into Native American territory led British officials to prohibit colonization west of the continental divide along the Appalachian Mountains in the hastily drafted Proclamation of 1763.

Front settlers seeking to organize more land protested this British policy. Resistance to centralized authority and hostility toward Indigenous peoples along the frontier therefore played a major role in the lead-up to the American Revolution. Interestingly, frontiersmen who resisted British colonial officials often disguised themselves as Native Americans, even before the famous Boston Tea Party, when men dressed as Native Americans threw tea into Boston Harbor in protest against British trade restrictions.

Unlike typical American histories, which tend to place all Native American tribes diametrically opposed to the colonists, Blackhawk emphasizes how tribes sometimes sided with the colonial powers, such as the French-Algonquian alliance in the Seven Years’ War. Complex narratives like these demonstrate how Native American tribes wielded power and influence in the geopolitical conflicts of colonial America, both in conflicts with colonists and in strategic alliances with colonial armies that strengthened their strategic position in a multipolar world.

Blackhawk explains: “The colonists moved inland after the Seven Years’ War and began building small farms and orchards and raising cattle and hogs. During the late 1750s and early 1760s, they were ready to conquer more land inland.

The Native Americans resisted this, and the British Crown, deciding that another war inland was too costly, issued a royal proclamation in 1763 to prevent its colonists from moving inland.

“The colonists defied British authority. One way they did this was by killing Native Americans who they believed were encouraging trade with Pontiac’s allies in places like Detroit and across a road between Philadelphia, a seaport city, and Pittsburgh, which had recently been founded and renamed after the future British Prime Minister William Pitt. Along this 300-mile stretch of road, known as Forbes Road, militias began raiding not only Native American communities they feared were trading with Pontiac, but also British supply trains, as the British attempted to make peace with Pontiac. These weren’t raiders. They were rebels. They were insurgents with a kind of political psychology designed to disrupt the loyalty of the native Indians.

The End of the Frontier

The author adds: “There the Revolution finds some of its most formative fuel. The idea of a frontier attacked by ‘merciless Indian savages’ appears in the Declaration of Independence. Where does that idea come from? American historians have failed to adequately explain the origins and genealogy of that language, that ideology, and essentially that history that would permeate the early republic.

“It is no coincidence that there are no federally recognized tribes in the states of Ohio and Pennsylvania, where these conflicts were most intense.”

The 1890 census was the first time censustakers could no longer draw a boundary between inhabited and uninhabited territory. Frederick Jackson Turner called this the “end of the frontier,” an event he considered a turning point in American history.

The frontier helped shape individualism and opposition to government control. Turner argued that westward migration and the establishment of new frontiers were transformative processes that shaped the idea of American exceptionalism. Not coincidentally, 1890 was also the date of the last “battle” between the US and a Native American people, the massacre at Wounded Knee Creek in North Dakota.

The perceived threat of the Native Americans was crucial, Blackhawk argues, for the formation of a central government that could extend its authority over national affairs. A federal constitution was drafted to unite the 13 states and manage their territorial expansion.

That alternative perspective is clear from the outset: While the nation may have been founded on the ideal of universal equality, readers should consider that turning points such as the Constitutional Convention, the Haitian Revolution, and the Louisiana Purchase “transformed and limited that concept,” especially as the newly formed and ever-changing systems of US government, naturalization, and property ownership, excluded more people than they admitted (p. 239).

New Century, Old Problems

In the chapters on the early twentieth century, Blackhawk highlights activists who worked to protect the rights of Native American peoples and preserve indigenous cultures. He highlights several well-known figures from Native history, such as Tisquantum, Pontiac, and Popé. The book also highlights influential Native women, such as Toypurina, Ada Deer, and Laura Cornelius Kellogg, who are often overlooked in settler or mainstream histories.

An important, yet sometimes overlooked figure, according to Leonard Carlson, associate professor emeritus at Emory University, was Charles Curtis, a member of the Een Kaw Nation. Curtis served as Speaker of the House of Representatives from 1929 to 1933, Senator from Kansas, and Vice President of the United States under Herbert Hoover.

Efforts to privatize Native American lands ended with the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 and the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act (also known as the Wheeler-Howard Act) in 1934. This law, drafted by John Collier, who became Commissioner of Indian Affairs, ended land allotments, the division of reservations into individual landholdings, and encouraged people on each reservation to adopt a written constitution that established formal tribal government within their reservations.

Blackhawk concludes his book at the end of the twentieth century, warning that Native American activism for justice and sovereignty must not rest: “At the beginning of the twenty-first century, continuing challenges to these sovereign gains resurfaced as members of Congress, judges, and other power centers refocused their attention on Indian lands, jurisdiction, and resources” (p. 445).

According to Anthony Earth, an international lawyer and foreign policy expert, this ongoing reckoning poses a different question than the one Blackhawk posed at the beginning of his book: “How can Indigenous peoples persuade the world’s leading democracy to atone for the injustices they have inflicted by dispossessing their homelands and ensuring that tribal sovereignty supports Indigenous self-determination?”

Answering that question presents serious challenges, especially in a divided America struggling to remain a leading democracy. Currently, atonement for past injustices against Indigenous peoples lacks political visibility and support, especially compared to campaigns for reparations for slavery.

But what tribal sovereignty and rights mean in the American political and legal order remains contested, as evidenced by recent Supreme Court cases involving Native American tribes and child custody, criminal law, and water rights. Therefore, according to Earth, the indigenous power praised by Blackhawk calls upon us to “imagine a future freed from historical facts. This responsibility is therefore an act of resistance to the past that dictates the future.”

Tribal Sovereignty

The book also highlights the contemporary achievements of the Native American civil rights movement, including the growing economic and political influence of reservations on the national stage.

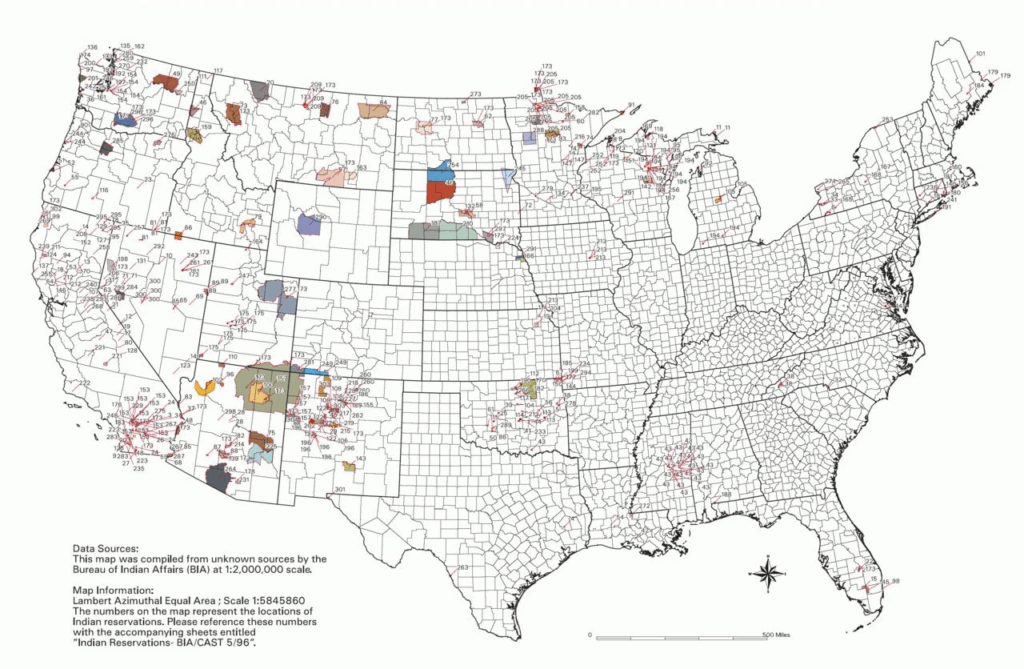

Tribes and their supporters have worked to defend tribal sovereignty. Since 1970, numerous groups have petitioned the federal government and have been recognized as tribes. Officially, there are 574 federally recognized American Indian and Alaska Native tribes in the United States today. These tribes are recognized as separate political entities with a governmental relationship with the U.S. federal government.

Each tribe has had to develop policies for its internal governance, resource management, and land administration. Blackhawk discusses some examples of complex legal issues that tribes faced in the latter half of the twentieth century. These include the question of whether a tribe can allow gambling on its lands even if the state in which the tribe resides prohibits gambling (tribal casinos and gambling rights are a significant source of revenue for some tribes), and legal battles in Washington state by Native communities to defend fishing rights established in treaties dating back to the 1850s.

In short

“The Rediscovery of America” effectively deconstructs common misconceptions about early American history for the uninitiated reader. It offers a useful starting point for readers unfamiliar with Indigenous perspectives on the subject.

Blackhawk’s retelling of American history acknowledges the enduring power and survival of Indigenous peoples, resulting in a more truthful picture of the United States.

Reference:

- Ned Blackhawk, The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of US History, Yale University Press, 2023, 616 pp.

Jan Servaes

Jan Servaes was UNESCO-Chair in Communication for Sustainable Social Change at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He taught 'international communication' in Australia, Belgium, China, Hong Kong, the US, Netherlands and Thailand, in addition to short-term projects at about 120 universities in 55 countries. He is editor of the 2020 'Handbook on Communication for Development and Social Change', and 'SDG18. Communication for All' (2 volumes, 2023).