Answers to existence of alien life might be found in Earth’s deep-sea volcanoes

UMass Amherst microbiologist James Holden lends his lifetime of experience with rare microbes to NASA effort to find life on Jupiter’s moon, Europa

University of Massachusetts Amherst

image:

UMass Amherst microbiologist James Holden readying the submarine that will travel to the ocean’s floor in search of microbial life.

view moreCredit: James Holden

AMHERST, Mass. — While popular culture commonly depicts extraterrestrial life as little green men with large, oval-shaped heads, it’s most likely that if there is life beyond our planet and within our solar system, it is microbial. Recently, NASA awarded University of Massachusetts Amherst microbiologist James Holden $621,000 to spend the next three years using his expertise to help predict what life on Jupiter’s moon Europa might look like. For that, Holden turned to an unexpected place: the volcanoes a mile beneath our own oceans.

Jupiter’s moon, Europa, has a frozen surface, but astronomers believe that beneath all that ice lies a salty, liquid ocean that is in contact with a hot molten core. “We think, based on our own planet, that Europa may have conditions that can support life,” says Holden, who points to the hydrothermal vents deep beneath our oceans’ surface. In fact, NASA’s recently launched Europa Clipper satellite is expressly designed to ascertain how habitable Europa may be.

Holden has spent his entire academic career studying the deep-sea vents that may be key to alien life. “I’ve been looking at deep-sea volcanoes since 1988,” he says. “To get our microbes from them, we use submarines—sometimes human-occupied, sometime robotic—to dive a mile below the surface and bring the samples ashore and back into my lab at UMass Amherst.”

Holden has built a lab that can reconstruct the lightless, oxygen-less conditions that these specialized microbes, which get their energy solely from the gases and minerals spewing out of the vents, love. “Because Europa’s conditions might be similar to the conditions these microbes come from,” Holden says, “we think that Europan life, if it exists, should look something like our own hydrothermal microbes.

“We have long had a basic interest in knowing if there is life beyond our planet and how that life would function,” Holden adds. “It’s exciting to think that the answer to the secret might be here on our own planet.”

But Europa is not Earth, its oceans are not ours and if microbial life does exist there, it probably doesn’t look exactly like ours.

“So, we need to figure out the different chemical processes that Europan microbial life might be using in order to create energy,” Holden says. “Different chemistries could create very different kinds of microbes.”

The hydrothermal microbes on Earth that Holden studies get their energy by breaking hydrogen down using special enzymes called hydrogenases. But there are different kinds of hydrogenases, they work in different ways and may have different functions in different kinds of cells.

Organisms that rely on different sets of hydrogenases may look and function very differently from each other. Furthermore, iron, sulfur and carbon coming from the vents are all adept at partnering with hydrogen by accepting its electrons to generate energy, but scientists aren’t yet sure exactly how those processes work biologically, especially as the amounts of hydrogen vary. “Our research will be to determine how the different chemical process contribute to an organism’s physiology,” says Holden.

A media kit, with images, video and all caption and credit information is available here.

Answers to Existence of Alien Life Might be Found in Earth’s Deep-Sea Volcanoes [VIDEO] |

The hydrothermal microbes Holden studies thrive in lightless, oxygen-less conditions a mile or more beneath the ocean’s surface.

About the University of Massachusetts Amherst

The flagship of the commonwealth, the University of Massachusetts Amherst is a nationally ranked public land-grant research university that seeks to expand educational access, fuel innovation and creativity and share and use its knowledge for the common good. Founded in 1863, UMass Amherst sits on nearly 1,450-acres in scenic Western Massachusetts and boasts state-of-the-art facilities for teaching, research, scholarship and creative activity. The institution advances a diverse, equitable, and inclusive community where everyone feels connected and valued—and thrives, and offers a full range of undergraduate, graduate and professional degrees across 10 schools and colleges and 100 undergraduate majors.

Contacts: James Holden, jholden@umass.edu

Daegan Miller, drmiller@umass.edu

UC Irvine astronomers discover scores of exoplanets may be larger than realized

The finding could impact search for extraterrestrial life

Irvine, Calif., July 14, 2025 — In new research, University of California, Irvine astronomers describe how more than 200 known exoplanets are likely much larger than previously thought. It’s a finding that could change which distant worlds researchers consider potential harbors for extraterrestrial life.

“We found that hundreds of exoplanets are larger than they appear, and that shifts our understanding of exoplanets on a large scale,” said Te Han, a doctoral student at UC Irvine and lead author of the new Astrophysical Journal Letters study. “This means we may have actually found fewer Earth-like planets so far than we thought.”

Astronomers can’t observe exoplanets directly. They have to wait for a planet to pass in front of its host star, and then they measure the very subtle drop in light emanating from a star. “We’re basically measuring the shadow of the planet,” said Paul Robertson, UC Irvine professor of astronomy and study co-author.

Han’s team studied observations of hundreds of exoplanets observed by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, and they found that light from neighboring stars can “contaminate” the light of a star an astronomer is studying. This can make any planet that’s passing in front of a star appear smaller than it truly is, because smaller planets block less light than bigger planets.

Han assembled hundreds of studies describing exoplanets discovered by the TESS mission, and he sorted the planets according to how various research teams measured the radii of exoplanets so he could estimate with the help of a computer model the degree to which those measurements were biased because of light contamination from neighboring stars. The team used observations from another satellite mission called Gaia to help them estimate just how much light contamination is affecting TESS’ observations.

“TESS data are contaminated, which Te's custom model corrects better than anyone else in the field,” said Robertson. “What we find in this study is that these planets may systematically be larger than we initially thought. It raises the question: Just how common are Earth-sized planets?”

The number of exoplanets thought to be similar in size to Earth was already small. “Of the single-planet systems discovered by TESS so far, only three were thought to be similar to Earth in their composition,” said Han. “With this new finding, all of them are actually bigger than we thought.”

That means that, rather than being rocky planets like Earth, the planets are more likely so-called “water worlds,” planets covered by one giant ocean that tend to be larger than Earth – or even larger, gaseous planets like Uranus or Neptune. This could impact the search for life on distant planets, because while water worlds may harbor life, they may also lack the same kinds of features that help life flourish on planets like Earth.

“This has important implications for our understanding of exoplanets, including among other things prioritization for follow-up observations with the James Webb Space Telescope, and the

controversial existence of a galactic population of water worlds,” said Roberston.

Next, Han and his team plan to use the new data to start reexamining planets previously thought uninhabitable due to their size and to also let other researchers know to exercise caution when interpreting data from satellites like TESS.

This research was supported in part by funding from NASA.

About the University of California, Irvine: Founded in 1965, UC Irvine is a member of the prestigious Association of American Universities and is ranked among the nation’s top 10 public universities by U.S. News & World Report. The campus has produced five Nobel laureates and is known for its academic achievement, premier research, innovation and anteater mascot. Led by Chancellor Howard Gillman, UC Irvine has more than 36,000 students and offers 224 degree programs. It’s located in one of the world’s safest and most economically vibrant communities and is Orange County’s second-largest employer, contributing $7 billion annually to the local economy and $8 billion statewide. For more on UC Irvine, visit www.uci.edu.

Media access: Radio programs/stations may, for a fee, use an on-campus studio with a Comrex IP audio codec to interview UC Irvine faculty and experts, subject to availability and university approval. For more UC Irvine news, visit news.uci.edu. Additional resources for journalists may be found at https://news.uci.edu/media-resources.

Journal

The Astrophysical Journal Letters

Article Title

Hundreds of TESS Exoplanets Might Be Larger than We Thought

Article Publication Date

14-Jul-2025

Astronomers find a giant hiding in the ‘fog’ around a young star

image:

When astronomers first observed it with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), they saw a smooth, planet-free disc, shown here in the right image. The team, led by Álvaro Ribas, an astronomer at the University of Cambridge, UK, gave this star another chance and re-observed it with ALMA at longer wavelengths that probe even deeper into the protoplanetary disc than before. These new observations, shown in the left image, revealed a gap and a ring that had been obscured in previous observations, suggesting that MP Mus might have company after all.

view moreCredit: ALMA(ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/A. Ribas et al.

Astronomers have detected a giant exoplanet – between three and ten times the size of Jupiter – hiding in the swirling disc of gas and dust surrounding a young star.

Earlier observations of this star, called MP Mus, suggested that it was all alone without any planets in orbit around it, surrounded by a featureless cloud of gas and dust.

However, a second look at MP Mus, using a combination of results from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission, suggest that the star is not alone after all.

The international team of astronomers, led by the University of Cambridge, detected a large gas giant in the star’s protoplanetary disc: the pancake-like cloud of gases, dust and ice where the process of planet formation begins. This is the first time that Gaia has detected an exoplanet within a protoplanetary disc. The results, reported in the journal Nature Astronomy, suggest that similar methods could be useful in the hunt for young planets around other stars.

By studying how planets form in the protoplanetary discs around young stars, researchers can learn more about how our own Solar System evolved. Through a process known as core accretion, gravity causes particles in the disc to stick to each other, eventually forming larger solid bodies like asteroids or planets. As young planets form, they start to carve gaps in the disc, like grooves on a vinyl record.

However, observing these young planets is extremely challenging, due to the interference from the gas and dust in the disc. To date, only three robust detections of young planets in a protoplanetary disc have been made.

Dr Álvaro Ribas from Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy, who led the research, specialises in studying protoplanetary discs. “We first observed this star at the time when we learned that most discs have rings and gaps, and I was hoping to find features around MP Mus that could hint at the presence of a planet or planets,” he said.

Using ALMA, Ribas observed the protoplanetary disc around MP Mus (PDS 66) in 2023. The results showed a young star seemingly all alone in the universe. Its surrounding disc showed none of the gaps where planets might be forming, and was completely flat and featureless.

“Our earlier observations showed a boring, flat disc,” said Ribas. “But this seemed odd to us, since the disc is between seven and ten million years old. In a disc of that age, we would expect to see some evidence of planet formation.”

Now, Ribas and his colleagues from Germany, Chile, and France have given MP Mus another chance. Once again using ALMA, they observed the star at the 3mm range, a longer wavelength than the earlier observations, allowing them to probe deeper into the disc.

The new observations turned up a cavity close to the star and two gaps further out, which were obscured in the earlier observations, suggesting that MP Mus may not be alone after all.

At the same time, Miguel Vioque, a researcher at the European Southern Observatory, was uncovering another piece of the puzzle. Using data from Gaia, he found MP Mus was ‘wobbling’.

“My first reaction was that I must have made a mistake in my calculations, because MP Mus was known to have a featureless disc,” said Vioque. “I was revising my calculations when I saw Álvaro give a talk presenting preliminary results of a newly-discovered inner cavity in the disc, which meant the wobbling I was detecting was real and had a good chance of being caused by a forming planet.”

Using a combination of the Gaia and ALMA observations, along with some computer modelling, the researchers say the wobbling is likely caused by a gas giant – less than ten times the mass of Jupiter – orbiting the star at a distance between one and three times the distance of the Earth to the Sun.

“Our modelling work showed that if you put a giant planet inside the new-found cavity, you can also explain the Gaia signal,” said Ribas. “And using the longer ALMA wavelengths allowed us to see structures we couldn’t see before.”

This is the first time an exoplanet embedded in a protoplanetary disc has been indirectly discovered in this way – by combining precise star movement data from the Gaia with deep observations of the disc. It also means that many more hidden planets might exist in other discs, just waiting to be found.

“We think this might be one of the reasons why it’s hard to detect young planets in protoplanetary discs, because in this case, we needed the ALMA and Gaia data together,” said Ribas. “The longer ALMA wavelength is incredibly useful, but to observe at this wavelength requires more time on the telescope.”

Ribas says that upcoming upgrades to ALMA, as well as future telescopes such as the next generation Very Large Array (ngVLA), may be used to look deeper into more discs and better understand the hidden population of young planets, which could in turn help us learn how our own planet may have formed.

The research was supported in part by the European Union’s Horizon Programme, the European Research Council, and the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI).

Journal

Nature Astronomy

Article Title

A young gas giant and hidden substructures in a protoplanetary disc

Article Publication Date

14-Jul-2025

Scientists at the Institute for High Energy Physics (HIHP) have announced that they have obtained sharp 150 GHz images of the Moon and Jupiter, the first step in the quest for "primordial gravitational waves." This project on the "roof of the world" is part of a network with similar observatories in Chile and Antarctica that seeks to gain insights into the earliest moments of the universe as we know it.

Beijing (AsiaNews/Agencies) – Using data from an observatory located 5,250 metres above sea level on a Tibetan plateau, Chinese astronomers are making progress in their investigations into the beginnings of the universe.

Scientists at the Institute of High Energy Physics (IHEP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences announced yesterday that their AliCPT-1 telescope captured the first clear images of the Moon and Jupiter at 150 GHz, a milestone that marks the official launch of China's hunt for so-called primordial gravitational waves, faint whispers from the dawn of time.

Born from quantum fluctuations in spacetime, these elusive signals are considered the purest ripples ever imprinted on the fabric of the cosmos.

“If we successfully detect primordial gravitational waves, we will glimpse the universe in its very first instant," said Zhang Xinmin, a researcher at the IHEP.

“At the same time, it can drive breakthroughs in cutting-edge technologies like cryogenic superconducting detectors and low-temperature readout electronics, thus propelling cosmology into an era of unprecedented precision," Zhang added.

Led by IHEP, the telescope was built over eight years by a global consortium of 16 partners, including the National Astronomical Observatories of China and Stanford University.

Located on the "roof of the world," the telescope is designed to escape atmospheric water vapour, which would drown out the whisper of primordial gravitational waves.

Only four sites on Earth are considered suitable for this type of observation: Antarctica, the Atacama Desert in Chile, the Qinghai Plateau in Tibet, and Greenland, said Liu Congzhan, a manager of the telescope experiment.

The experiment on the moon and Jupiter is just the start, said Li Hong, also a researcher at IHEP.

“As the Northern Hemisphere's first high-altitude primordial gravitational-wave observatory, the telescope fills a gap for China and, together with devices in Antarctica and Chile, completes a global, complementary network.”

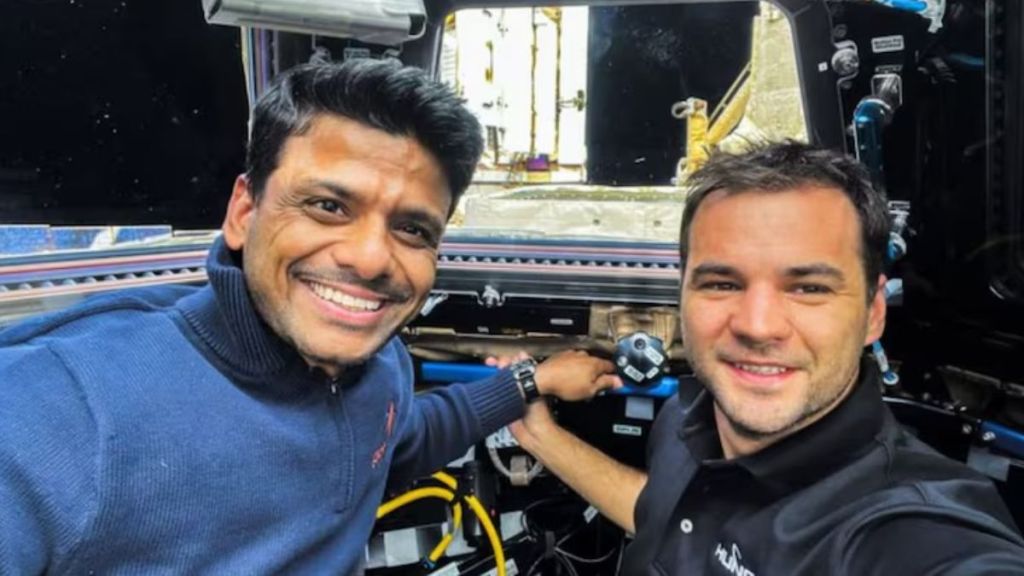

During his stay aboard the ISS, Shukla, along with his Ax-4 crewmates, completed over 60 cutting-edge scientific experiments.

Written by FE Online

Updated: July 14, 2025

Shubhanshu Shukla to retrn to Earth on Tuesday: Group Captain Shubhanshu Shukla has etched his name in history as the first Indian astronaut to visit the International Space Station (ISS). Serving as mission pilot for Axiom Mission 4 (Ax-4), Shukla played a pivotal role in an 18-day journey that marked a new chapter in India’s growing space ambitions. He is scheduled to undock from the ISS at 4:30 pm IST on July 14, with a splashdown expected in the Pacific Ocean off the California coast around 3:00 pm IST on July 15.

ALSO READ

Shubhanshu Shukla begins return to Earth today, says ‘India is still saare jahan se accha’ after historic ISS mission

Scientific contributions

During his stay aboard the ISS, Shukla, along with his Ax-4 crewmates, completed over 60 cutting-edge scientific experiments. Among his most significant contributions was the Sprouts Project, which investigated how microgravity affects seed germination and early plant development which is critical research for future space agriculture and food sustainability on long-duration missions.

Another key focus was microalgae research, exploring their utility in generating oxygen, producing food, and synthesising biofuels, components essential for supporting life in space. Shukla also conducted trials on glucose monitoring devices in microgravity, an important step toward enabling astronauts with diverse medical needs to safely participate in long-term spaceflight.

Several of the experiments he worked on including at least seven designed by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) are expected to deliver valuable insights for India’s upcoming Gaganyaan human spaceflight programme.

Bridge between scientists and space

Speaking during a conversation with Axiom Space Chief Scientist Dr. Lucie Low, Shukla said, “It is exciting and a joy to do this.” Reflecting on his role, he added, “I feel proud to be this kind of a bridge between the researchers and the station and do the research on behalf of them.”

The Sprouts Project was led by Dr Ravikumar Hosamani (University of Agricultural Sciences, Dharwad) and Dr Sudheer Siddapureddy (IIT Dharwad), and its results may reshape how we understand plant biology in space. Shukla also contributed to crop seed research by photographing six varieties for post-mission genetic evaluation. He worked across domains, from plant biology to cognitive load analysis on astronauts, and expressed particular excitement for the stem cell research he conducted, aimed at improving recovery and healing in space environments.

Shukla’s farewell on ISS

At a farewell ceremony aboard the ISS on July 13, Shukla expressed heartfelt gratitude to ISRO, his international crewmates, and the Indian public. He described the mission as “a proof of what humanity can achieve together,” and voiced his hope that it would inspire the youth of India to “dream beyond boundaries.”

ALSO READ

‘We refused to…’: ISRO chief reveals how mission carrying Shubhanshu Shukla was ‘saved’ from disaster

Evoking the spirit of Rakesh Sharma, India’s first man in space, Shukla said, “India is still saare jahan se accha,” adding that from space, India looks “ambitious, fearless, confident, and proud.”

Published : July 14, 2025 -

Korea Herald

NEW YORK (AP) — For sale: A 25-kilogram rock. Estimated auction price: $2 million-$4 million. Why so expensive? It's the largest piece of Mars ever found on Earth.

Sotheby's in New York will be auctioning what's known as NWA 16788 on Wednesday as part of a natural history-themed sale that also includes a juvenile Ceratosaurus dinosaur skeleton that's more than 2 meters tall and nearly 3 meters long.

According to the auction house, the meteorite is believed to have been blown off the surface of Mars by a massive asteroid strike before traveling 225 million kilometers to Earth, where it crashed into the Sahara. A meteorite hunter found it in Niger in November 2023, Sotheby's says.

The red, brown and gray hunk is about 70 percent larger than the next largest piece of Mars found on Earth and represents nearly 7 percent of all the Martian material currently on this planet, Sotheby's says. It measures nearly 375 millimeters by 279 millimeters by 152 millimeters.

"This Martian meteorite is the largest piece of Mars we have ever found by a long shot," Cassandra Hatton, vice chairman for science and natural history at Sotheby's, said in an interview. "So it's more than double the size of what we previously thought was the largest piece of Mars."

It is also a rare find. There are only 400 Martian meteorites out of the more than 77,000 officially recognized meteorites found on Earth, Sotheby's says.

Hatton said a small piece of the red planet remnant was removed and sent to a specialized lab that confirmed it is from Mars. It was compared with the distinct chemical composition of Martian meteorites discovered during the Viking space probe that landed on Mars in 1976, she said.

The examination found that it is an "olivine-microgabbroic shergottite," a type of Martian rock formed from the slow cooling of Martian magma. It has a course-grained texture and contains the minerals pyroxene and olivine, Sotheby's says.

It also has a glassy surface, likely due to the high heat that burned it when it fell through Earth's atmosphere, Hatton said. "So that was their first clue that this wasn't just some big rock on the ground," she said.

The meteorite previously was on exhibit at the Italian Space Agency in Rome. Sotheby's did not disclose the owner.

It's not clear exactly when the meteorite hit Earth, but testing shows it probably happened in recent years, Sotheby's said.

The juvenile Ceratosaurus nasicornis skeleton was found in 1996 near Laramie, Wyoming, at Bone Cabin Quarry, a gold mine for dinosaur bones. Specialists assembled nearly 140 fossil bones with some sculpted materials to recreate the skeleton and mounted it so it's ready to exhibit, Sotheby's says.

The skeleton is believed to be from the late Jurassic period, about 150 million years ago, Sotheby's says. It's auction estimate is $4 million to $6 million.

Ceratosaurus dinosaurs were bipeds with short arms that appear similar to the Tyrannosaurus rex, but smaller. Ceratosaurus dinosaurs could grow up to 7.6 meters long, while the Tyrannosaurs rex could be 12 meters long.

The skeleton was acquired last year by Fossilogic, a Utah-based fossil preparation and mounting company.

Wednesday's auction is part of Sotheby's Geek Week 2025 and features 122 items, including other meteorites, fossils and gem-quality minerals.

khnews@heraldcorp.com

by Paul Arnold, Phys.org

JULY 14, 2025 REPORT

The GIST

edited by Gaby Clark, reviewed by Andrew Zinin

Editors' notes

Folding of A4 sheet into "paper dart." Credit: Acta Astronautica (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.actaastro.2025.06.052

Space junk is a huge problem. The surge in satellite launches in recent years is leaving low Earth orbit (LEO) cluttered with debris such as discarded rocket bodies, broken parts and defunct satellites. Beyond the risk of debris colliding with working satellites that are vital for navigation, communication and weather forecasting, large pieces could come crashing back down to Earth.

Space junk may also be a threat to the environment. Old rockets and satellites burn up when they re-enter the atmosphere, leaving a trail of chemicals behind that could damage the ozone layer. The more we launch, the messier LEO gets, and the bigger the problems become.

Space agencies and private companies are looking at ways to clear up the litter we leave behind, but they're also exploring how to build more sustainable rockets and satellites, using organic polymers instead of metals. In a new study, published in Acta Astronautica, researchers turned to origami, the ancient Japanese art of paper folding, to find a sustainable alternative.

Paper planes in space

Maximilien Berthet and Kojiro Suzuki from the University of Tokyo wondered what would happen if a paper plane were launched from the International Space Station (ISS) at a height of 400 kilometers and a speed of 7,800 meters per second, similar to that of the orbiting station. They wanted to know how long it would take to fall back into the Earth's atmosphere and how much heating it could endure, among other things.

Experimental setup inside the test section of the UT Kashiwa Hypersonic and High Enthalpy Wind tunnel. Credit: Acta Astronautica (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.actaastro.2025.06.052

Initially, the plane remained stable due to the way it was folded, gliding smoothly in the vacuum-like conditions of space, according to the software simulations. But then after four days, when it reached about 120 kilometers above the Earth, things took a different turn. The plane tumbled and started to spin out of control.

"The paper space plane's extremely low rotational inertia and aerodynamic static margin enable it to passively maintain a stable flow-pointing orientation for most of atmospheric entry," explained the researchers in their paper.

"Below around 120 km altitude, tumbling motion is expected, accompanied by severe aerodynamic heating resulting in burn-up in the atmosphere at around 90–110 km altitude."

Combined paper and aluminum space plane model for use in wind tunnel, (a) before and (b) after being set up inside the test section. Credit: Acta Astronautica (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.actaastro.2025.06.052

Physical model

Berthet and Suzuki also built a physical model of their plane made from paper with an aluminum tail. They put it into the Kashiwa Hypersonic and High Enthalpy Wind Tunnel at the University of Tokyo to see how it would hold up under conditions similar to re-entry. They subjected it to Mach 7 for seven seconds, during which the nose bent back, and there was some charring on the wing tips, but it didn't disintegrate. However, it would have burned up had the experiment gone on for longer.

One small step

This research shows how a simple idea could inspire a more sustainable approach to tackling the problem of space debris. The study's authors also suggest paper-based spacecraft could play a role in future missions, such as gathering data about the Earth, then burning up completely without leaving harmful material behind. It's a small step, but one that could make our forays into space better for the environment and safer for us down on the ground.

Written for you by our author Paul Arnold, edited by Gaby Clark, and fact-checked and reviewed by Andrew Zinin—this article is the result of careful human work. We rely on readers like you to keep independent science journalism alive. If this reporting matters to you, please consider a donation (especially monthly). You'll get an ad-free account as a thank-you.

More information: Maximilien Berthet et al, Study on the dynamics of an origami space plane during Earth atmospheric entry, Acta Astronautica (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.actaastro.2025.06.052

Journal information: Acta Astronautica

© 2025 Science X Network