The New Frontline: How Geoeconomics Is Rewriting Global Power Dynamics – Analysis

When European leaders met Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing in July 2025, the diplomacy was extravagant, but the underlying tensions could not be ignored. The EU cited a record €360 billion trade deficit with China, condemned Beijing for distorting global markets with massive industrial subsidies, and threatened tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles. Beijing subsequently signalled tight retaliatory curbs on key rare earth exports in response. It was more than an appropriate diplomatic spat; it was the new war. No tanks, no missiles, no other form but trade tariffs, investment bans, or tech controls.

Welcome to geoeconomic war.

Geoeconomic warfare, in its simplest terms, is the use of economic means — sanctions, trade restrictions, cyberattacks, investment screening — to achieve national security objectives. This symbolises the transition from troops to diplomats — from bullets and bombs to currencies, data, and supply chains. This is less direct than kinetic war, but no less disruptive.

Recent Geoeconomic Flashpoints

A flow of geoeconomic confrontations has unfolded in the last few years. Russia has endured an 18th round of Western sanctions in 2024 over the Ukraine invasion, with various restrictions on LNG shipping and other key tech exports. China faced sanctions for allegedly sending dual-use items to Russia’s military effort. Beijing, in response, used its dominant position over critical minerals like gallium and germanium, essential for global chip production. If anything, these economic weapons caused greater harm than conventional war, cutting off economies from each other, diverting trade routes, and disaggregating global systems.

The US also ramped up its economic war on China with new semiconductor trade restrictions, expansion and AI firms using advanced GPUs blocklist in 2025. In response, China targeted US carmakers in mainland China, retaliating against earlier punitive tariffs on agricultural goods.

The US, and especially under a new administration, has imposed broad “reciprocal tariffs” since early 2025, a significant directional change toward protectionism. Beginning on April 2, 2025, there was an initial 10% tariff on all imports into the US from around the world, with a further increased rate on more than 60 economies that were identified as the “worst offenders” or where there was a significant bilateral trade surplus with the US. Those are sanctions established under various legal authorities, such as the IEEPA, with the aim of eliminating trade imbalances and employing economic leverage.

The US effective tariff rate has skyrocketed to the highest level in more than a century, evoking the protectionism of the 1930s. Exporters to the US from countries including the European Union, Japan, Vietnam, Taiwan, and Cambodia now face tariffs that are 20% to almost 50% higher than before. Supporters have welcomed a more aggressive use of tariffs as a weapon in an ongoing effort to address domestic and international trade imbalances. However, opponents warn of a disastrous global trade war in which many of America’s key trading partners have already issued countermeasures and threaten to issue more, even further breaking up global supply chains.

The Role of Multinational Corporations (MNCs)

In this new style of warfare, multinational corporations (MNCs) have emerged to serve as both targets and tools. Apple, Samsung and TSMC are caught between the US demand to “de-risk” from China and the Chinese insistence on local compliance. Hostility towards Tesla through audits or data law crackdowns in China is not merely regulatory friction: instead, it has strategic intent behind it. Corporations are now in a game where national loyalty can matter more than market logic.

Reconfiguring Alliances and Power

Geoeconomic warfare also reconfigures global alliances. The Global South that was once lured by aid is now being wooed with infrastructure and access to markets. New configurations of power around BRICS, the Chinese Belt and Road initiative, and alternatives to SWIFT — like China’s CIPS — are changing flows of power around the world. The West faces a threat from China not through any conventional war but through a geoeconomic counter-system.

Impact on Bangladesh: Opportunity and Risk

For a country like Bangladesh, this new order brings opportunity and Danger. Bangladesh: Balancing on a Tightrope as the New hub of the Indo-Pacific and takes advantage of Chinese infrastructure investment, such as ports and energy projects, within the framework of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. However, its geography makes it a vital ground of US interest in its Indo-Pacific Strategy.

Too much reliance on Chinese financing could lead to debt dependency. Recently disruption in the global shipping lane Houthi attack in the Red Sea, has directly affected our garments sector from exporting to Europe.

The global shift in tariffs is also seen in Bangladesh. The US has recently declared a 35% so-called “reciprocal tariff” on imports from Bangladesh, effective from August 1, 2025. This was a decrease against an earlier 37% tariff on Bangladeshi apparel exports, which had been imposed on April 1 2015, resulting in an effective increase on the previous average of 15%. Even in conjunction with the existing 54% tariff on Bangladeshi goods, this could mean a total tariff burden exceeding 50%.

The basis for such a high tariff, contested by officials from Bangladesh, is a USTR (US Trade Representative), which puts the overall combined tariff, para-tariff and non-tariff barriers against US imports from Bangladesh at 74%. In Bangladesh, this decision has raised significant concerns, especially for the ready-made garment (RMG) industry that makes up more than 80% of the whole country’s exports and provides millions of jobs, especially for women.

The US is the largest destination for Bangladesh garments. This puts Bangladesh at a special disadvantage. Bangladeshi officials and industry leaders are in talks with the US to soften the blow. However, the measure is widely viewed as a geoeconomic coercion, possibly aimed at Bangladesh for its growing economic ties with China and its non-signing of some fundamental security deals with the US. These retaliatory tariffs would also lower Bangladesh’s GDP growth, warned the Asian Development Bank (ADB)

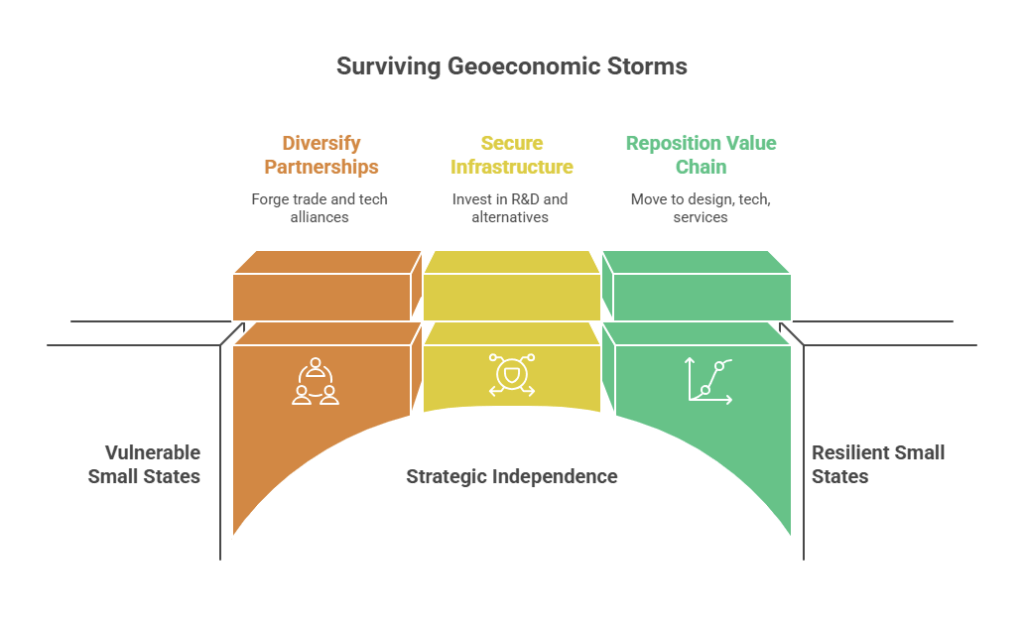

How the small states survive this geoeconomic Storm?

- Strategic diversification is key. Countries such as Bangladesh reducing over-reliance on any one power. Trade, investment, and technology partnerships would have to be made between China, the West, the Middle East, and ASEAN.

- The digital and financial sovereignty. With cyberattacks and payment network being targeted, countries have to now invest more in R&D to build their own secure infrastructure and regional alternatives.

- Value chain repositioning is vital. To avoid becoming collateral damage in low-end economic wars, Bangladesh needs to climb up the value chain quickly from basic textiles to design, tech, and services.

The days of military empires are over, and economic coalitions are on the rise. The control of flows of chips, data, energy, capital has now passed into the hands of those who control flows. It is an invincible Battlefield.

As the Fog of the new kind of hybrid conflict gets thicken, The wisest strategy would be

“In the age of economic warfare, sovereignty does not belong to the strongest; it belongs to the most adaptable”

Sources

- 1. The Washington Post. (2025, July 24). Rebalancing relationship with China ‘essential,’ E.U. president says. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/07/24/eu-china-leaders-meet/

- 2. The Financial Times. (2025, June 11). Ursula von der Leyen tells Xi Jinping EU-China ties are at ‘inflection point.’ Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/268b2852-e83c-4676-9f3c-7ca41c12c1ba

- 3. The Guardian. (2025, June 11). US and China agree framework deal to extend trade war truce. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jun/11/us-china-trade-talks-framework-deal-amid-dispute-over-rare-earths

- 4. The New York Post. (2025, July 24). Nvidia AI chips worth $1B sold to China despite US export controls. Retrieved from https://nypost.com/2025/07/24/business/nvidia-ai-chips-worth-1b-sold-to-china-despite-us-export-controls-report/

- 5. AP News. (2025, July 18). EU and UK impose new sanctions on Russia. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/article/ce7b2fa3ebb4e07cc3251b456a5e99af

Md. Towhid Bin Shafi

Md. Towhid Bin Shafi is a policy analyst and academic based in Dhaka, Bangladesh. He holds a Master’s in International Relations and an MBA, with a research focus on global governance, economic diplomacy, and security studies. He currently serves as Director of Administration and Execution at the Canadian University of Bangladesh, where he is also involved in Student affairs initiatives. He has Military experience of 10 years and also served in UN Peace Keeping operation MINUSCA.