EPSTEIN FILES

Why Was The Dalai Lama At Jeffrey Epstein’s House?

Last month, on the Daily Beast podcast, journalists Joanna Coles and Michael Wolff took turns reeling off a list of famous people who Wolff met while visiting Jeffrey Epstein’s Manhattan home. The recited names were a who’s who of rich, powerful, and perverted men, many of them recognized Friends of Jeffrey. But one name stood out as unusual: the Dalai Lama. (The list of names starts at about the 18:25 timestamp on the full recording.)

Coles thought so too, asking Wolff, “Did you actually meet the Dalai Lama at Jeffrey Epstein’s?”

“Indeed,” said Wolff.

Asked why the Dalai Lama was there, Wolff said that a lot of people hung out with Epstein to try to wheedle money out of him. And there was something compelling about the upscale salon-like scene: “It was always extraordinary,” said Wolff.

Wolff said that he started spending time at Epstein’s house in 2014, six years after the infamous pedophile was given an extremely favorable plea deal for sex crimes charges because, former U.S. district attorney Alex Acosta once said, “I was told Epstein ‘belonged to intelligence’ and to leave it alone.” Wolff was working on a potential book about Epstein and was given access to the now-deceased sex offender’s wealthy social milieu. Epstein later became an important source for Wolff’s best-selling books about President Donald Trump.

Any writing about Michael Wolff seems to require the proviso that his reliability has been questioned by assorted enemies and media critics. Wolff is a gossip hound, practicing the art at a very high level, and he hangs out with unsavory politicians and oligarchs who might like the idea of having a famous journalist around — until he publishes a book about them. Wolff gets into marble-floored rooms that many journalists don’t, so his comments are worth considering.

With that throat-clearing aside, let’s consider why His Holiness the Dalai Lama may have been at now-deceased sex trafficker and pedophile Jeffrey Epstein’s house. People generally hung out with Epstein for two reasons: sex and money. Wolff suggested that, in this case, it was the latter. Did the Dalai Lama, or an organization with which he’s associated, receive a donation from Epstein?

The Dalai Lama’s press office did not respond to an emailed list of questions. I was unable to reach Michael Wolff for comment about the Dalai Lama’s visit to Epstein’s home.

It wouldn’t be the first time the Dalai Lama had received money from a sex trafficker. In 2009, the Tibetan spiritual leader spoke at an event for NXIVM, the abusive sex cult whose leader, Keith Raniere, was convicted in 2019 on seven criminal charges and sentenced to 120 years in prison. During the 2009 appearance, the Dalai Lama gave a speech and placed a ceremonial Tibetan scarf on Reniere’s shoulders. For his efforts, the Dalai Lama reportedly received $1 million. The deal was made by billionaire heiress Sara Bronfman, who, along with her sister Clare, gave Raniere and NXIVM at least $150 million. Sara Bronfman was alleged to be having an affair with the Lama’s personal peace emissary Lama Tenzin Dhonden, who was later removed from his post for corruption.

Despite evidence that he ran a child sex trafficking operation, the source of Epstein’s wealth has never been sufficiently accounted for. People who spent time around him have said that they didn’t know what he did for a job and that he seemed to do very little actual work. For some reason, billionaires liked to give Jeffrey Epstein huge amounts of money. Les Wexner gave Epstein tens of millions of dollars — he later said that Epstein misappropriated $46 million from him — along with one of the most valuable residential properties in New York City. Leon Black, who has been accused of rape in civil suits, paid Epstein $158 million for “tax advice.”

Whatever Epstein was as a financier — sometimes he was described as a financial bounty hunter, reclaiming assets stranded overseas — he was adept at moving money around the world. And he had help from pliant bankers, as demonstrated by victims’ lawsuits against JPMorgan Chase and Deutsche Bank, which led to nine-figure settlements. Sen. Ron Wyden recently said that the Treasury Department has documents about banks looking the other way for more than $1.5 billion in Epstein-related financial activity, and that Treasury should release the documents. Wyden, who has overseen a long-running investigation into Leon Black’s taxes, also said that Black’s payments to Epstein should be investigated by the IRS.

In short, there’s still so much we don’t know about where Epstein’s money came from and where it went — and to what ends. But following the money trail as far as it leads can tell us something about Epstein’s network, how he operated, and who enabled him. And sometimes a single $50,000 payment can open up the aperture, letting in some light.

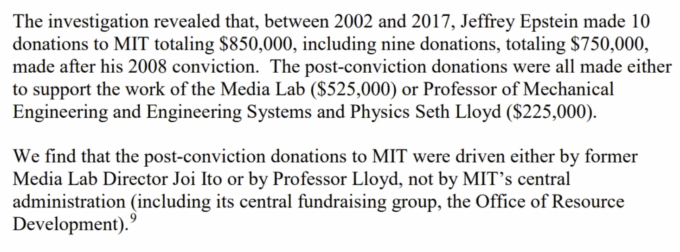

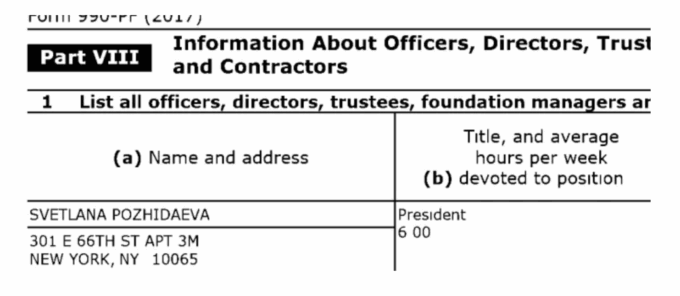

In the official 2020 MIT report regarding Epstein’s relationship with the university, two partners from the law firm Goodwin Procter “analyzed all donations received by MIT, both those made directly by Epstein (whether individually or through his charitable foundations) and those made by third parties at Epstein’s alleged behest.” The report found that, during a 15-year period, Epstein donated a combined $850,000 to Seth Lloyd, a physics professor, and to the MIT Media Lab, which was then headed by Joi Ito. Michael Wolff mentioned Joi Ito as one of the prominent guests who attended Epstein’s regular home gatherings.

The report claims that Lloyd, who was placed on administrative leave before being allowed to return to teaching, accepted transfers from Epstein in his personal bank account and tried to conceal the source of the donations. The report similarly describes MIT officials as trying to keep quiet Epstein’s donations to the Media Lab and his visits to campus.

The report doesn’t look at relationships between MIT staff and Epstein that occurred outside the university. While the authors write that they looked into donations that may have come through Epstein proxies, it’s not clear how far that investigation went, or was allowed to go. Former MIT Media Lab director Joi Ito received at least $1.2 million from Epstein for his own venture capital firm, which the MIT report mentions in a footnote.

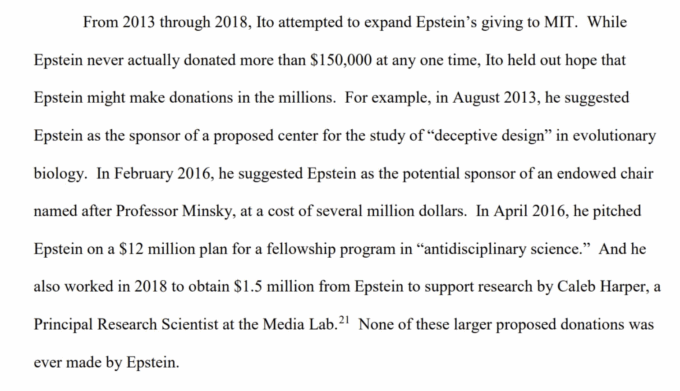

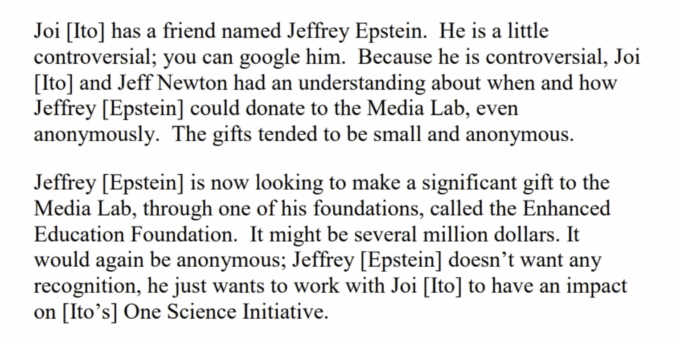

The MIT Media Lab had an uncommonly high profile for a university organization, with an orbiting network of billionaire tech moguls, scientists, writers, government officials, politicians, and TED-talking NGO types. That made the Media Lab’s director, Joi Ito, an important relationship for the prestige-obsessed Epstein. The two seemed to be in close contact, with Ito once “strategizing with [Epstein] as to how he might be able to ‘mollify the bad press’ after a series of articles were published concerning a civil lawsuit brought by Epstein victims,” according to the MIT report. Ito, who sat on the boards of the New York Times and the MacArthur Foundation, repeatedly solicited Epstein for more money for the university. MIT’s investigators claimed that his big-money asks weren’t answered:

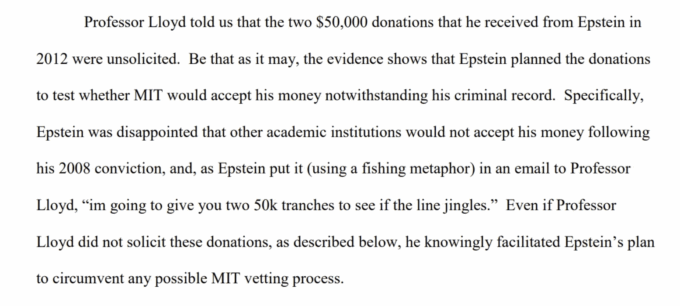

Epstein used ostensibly philanthropic donations in order to win favors, borrow academics’ intellectual prestige, or to move money where it wouldn’t normally be allowed to go. The MIT report describes Epstein using Professor Lloyd (with the professor’s participation) to see if he could make donations to the university without setting off alarm bells:

In November 2013, Linda Stone, who first introduced Epstein to Ito, sent an email to Ito suggesting that a 501(c)(3) might be used to mask Epstein’s donations, although, she wrote, “there may be disclosure issues.” Ito then took the idea to MIT’s VP of Development, according to the MIT report.

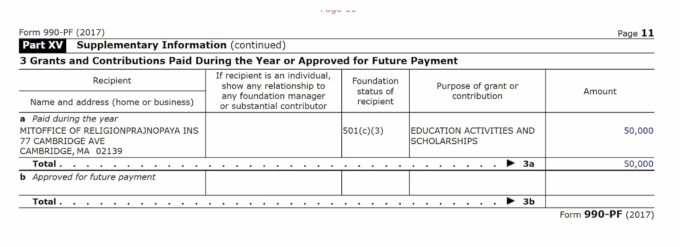

In 2017, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit called Education Advance donated $50,000 to the Prajnopaya Institute at MIT. The money for that donation came from an entity called “J Epstein Virgin Islands FD Inc,” which that same year gave Education Advance $55,000, according to IRS filings. Education Advance took in an additional $1,500 in 2017, which appears to be the only year it was ever in operation. Its IRS filings report no other donations or dispersal of funds, suggesting that Education Advance might have been purpose-made for the Prajnopaya Institute gift. After 2017, Education Advance never filed another Form 990, leading to its nonprofit status being revoked.

Education Advance was overseen by Svetlana Pozhidaeva, a Russian model who worked for MC2, a modeling agency run by Jean-Luc Brunel, an Epstein accomplice accused of rape and sex trafficking who died in a French prison in 2022. Education Advance was registered to an Epstein-owned Manhattan building. Pozhidaeva, who had been photographed leaving Epstein’s house, also shared a lawyer with him: Darren Indyke, who is now co-executor of Epstein’s estate. Epstein’s Virgin Islands-based foundation, the initial source of the funds, was sometimes called Enhanced Education.

The Prajnopaya Institute transaction isn’t mentioned in the 2020 MIT report, which covers the years “between 2002 and 2017.” The existence of the transaction had been reported a year earlier by the Daily Beast. MIT’s media office did not respond to questions about why the Prajnopaya Institute donation did not appear in its 2020 report on the university’s relationship with Epstein.

The lack of official acknowledgement from MIT is another indicator that Epstein’s money flows remain poorly charted. Some parties might prefer it that way. Epstein also helped muddy the waters by lying and exaggerating about the scope of his charitable giving — a deception that included Epstein making edits to Wikipedia pages about himself, his foundation, and some of his associates.

The Prajnopaya Institute told the Daily Beast in 2019 that it returned the $50,000 donation. The Institute didn’t respond to an email asking how the donation was brokered and if the Dalai Lama or Tenzin Priyadarshi was involved. A separate inquiry to Priyadarshi, sent through his website imonk.org, received no reply.

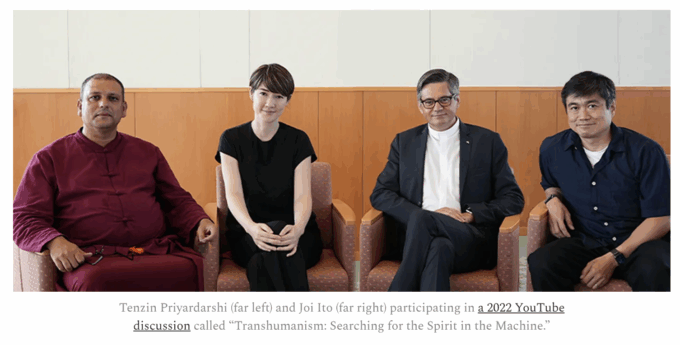

Priyadarshi has long been associated with the Media Lab and Joi Ito, who described Priyadarshi as his friend. They podcasted together and co-taught an MIT class called Principles of Awareness. Ethics programs that began in the Media Lab later moved to the Dalai Lama Center, where Priyadarshi is CEO. Ito and Priyadarshi have appeared on discussion panels together. Ito, a prolific photographer, has posted photos of Priyadarshi and the Dalai Lama, and he’s cited them in his writing. The Dalai Lama has attended at least three events hosted by the MIT center named after him.

Dr. Babak Babakinejad, an MIT whistleblower and research scientist who first alerted me to the Prajnopaya Foundation donation, offered the following statement:

“The MIT Epstein report is institutionally compromised. MIT has persistently resisted transparency regarding Epstein’s connections to the Media Lab and its associated initiatives, particularly regarding Open Agriculture and its Food Computers. This project is implicated in fraud, environmental misconduct, and retaliation. These are issues I have been actively challenging as part of an ongoing lawsuit.”

Epstein’s interest in MIT was about more than just showering a couple programs he liked with cash. Epstein visited MIT’s campus at least nine times and attended MIT Media Lab events, which could attract wealthy tech and political figures like billionaire Reid Hoffman. Epstein spent time with MIT professors and staffers, some of whom he met through the literary agent John Brockman, who acted as a connector between Epstein and scientists and academics. It’s hard to think that Epstein’s MIT-related contributions during a 15-year period only amounted to $850,000, especially when the donations that are now documented were once obfuscated. As shown here, the Prajnopaya Institute donation means the real amount that Epstein gave to MIT is at least $900,000.

It’s not clear why Epstein, who as far as I can tell never mentioned Buddhism or had any association with Tibetan culture or causes, made a $50,000 donation to a Buddhist organization at MIT. Perhaps someone influential asked him. Perhaps he was once again looking “to see if the line jingles.”

The alarm did go off after all, but it was too late for anyone to care.

This piece first appeared on Jacob Silverman’s Substack.