Can AI persuade you to go vegan—or harm yourself?

Large language models are more persuasive than humans, according to recent UBC research.

Their vocabulary, perceived empathy and ability to provide tangible resources in seconds add to their persuasiveness, which has led to growing concerns and ongoing lawsuits about the potential for AI chatbots to cause harm to users.

In this Q&A, Dr. Vered Shwartz, UBC assistant professor of computer science and author of the book Lost in Automatic Translation, discusses her findings as well as potential safeguards for the future of AI.

Why does the persuasiveness of AI matter?

VS: Large language models like ChatGPT are already widely used to create content that can influence human beliefs and decisions, whether in art, marketing, news dissemination and more. They can quickly produce large amounts of text at scale. If they’re persuasive, there’s a real risk that people will use them to manipulate others for malicious purposes. We may be past the point of deciding whether they should be used in these areas, and instead need to focus on finding ways to protect against the malicious uses.

What did you find?

VS: We wanted to see how persuasive large language models such as ChatGPT can be when it comes to lifestyle decisions: whether to go vegan, buy an electric car or go to graduate school. We had 33 participants pretend to be considering these decisions, and then interact with either a human persuader, or GPT-4, via chat. Both human persuaders and GPT-4 were given general tips about persuasion, and the AI was instructed not to reveal it was a computer. Participants were asked before and after the conversation how likely they were to adopt the lifestyle change.

Participants found the AI more persuasive than humans across all topics, but particularly so when convincing people to become vegan or attend graduate school.

Human persuaders, however, were better at asking questions to find out more information about the participant.

What makes AI persuasive?

VS: The AI made more arguments and was more verbose, writing eight sentences to every human persuader’s two. One of the main factors for its persuasiveness was that it could provide concrete logistical support, for instance, recommending specific vegan brands or universities to attend.

It used more ‘big words’ of seven letters or more, such as longevity and investment, which perhaps made it seem more authoritative. And, people found their AI conversations more pleasant, with GPT-4 agreeing with users more often, and uttering more pleasantries.

What safeguards do we need?

VS: AI education is crucial. Some giveaways do still exist—for instance, almost all our participants worked out that they were speaking to an AI—but we’re getting close to the point where it will be impossible to tell if you’re chatting with AI or a human, so we need to make sure people know how these tools work, how they are trained and so, how they are limited. AI can hallucinate and get things wrong. It’s important to know that, for instance, the AI summary at the top of your search page might not be true.

Another key is general critical thinking. If something seems too good or too bad to be true, we need to investigate it. Check where information is coming from. Is it a trustworthy and known source?

When it comes to AI affecting mental health, companies could implement warning systems if someone is writing harmful or suicidal text.

We don’t really have full control over these models. Instead of companies rushing to monetize AI, there should be more thought about implementing guardrails effectively and widely. This could include looking beyond generative AI and its inherent limitations to different paradigms. We don’t need to put all our eggs in one basket.

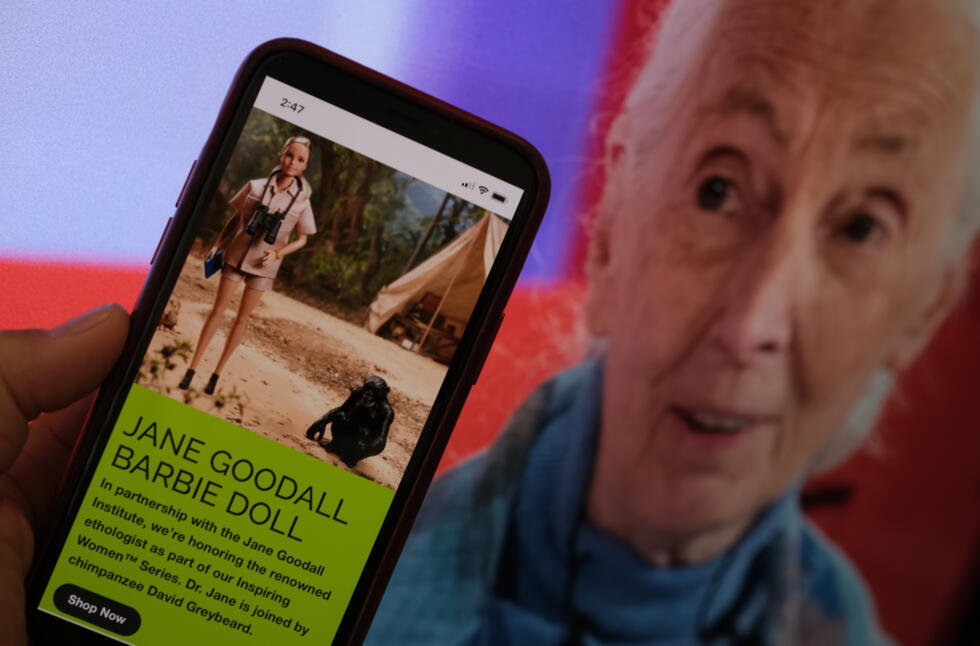

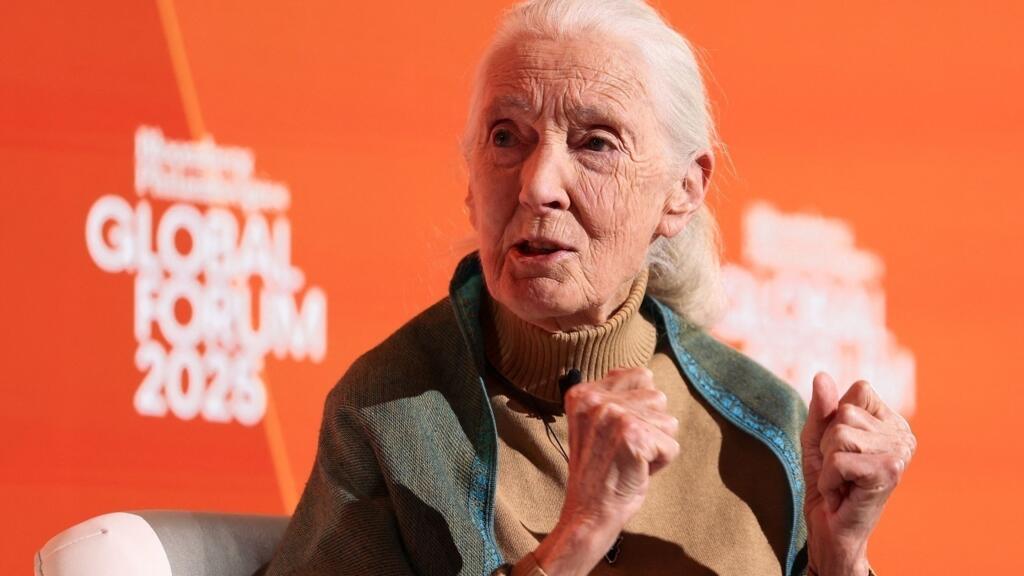

Primatologist Jane Goodall, who has spent her life researching and fighting for the conservation of chimpanzees, pictured in Entebbe in 2018 © SUMY SADURNI / AFP/File

Primatologist Jane Goodall, who has spent her life researching and fighting for the conservation of chimpanzees, pictured in Entebbe in 2018 © SUMY SADURNI / AFP/File