Gary Stevenson has risen to fame on the back of his 2024 Sunday Times bestseller, Trading Game; an edgy rags to riches tale. Boy grows up poor in the London suburb of Ilford, in view of the Canary Wharf skyline. He progresses from a paper round to DFS stores selling bedwear. He and his family are often short of money. In school, he excels at maths. He applies for college and lands a place in the London School of Economics by winning a card game played with other applicants. He is in, with accompanying opportunities; which for him, turn out to be a job as currency trader in Citibank, in one of those Canary Wharf skyscrapers he used to gaze at. He quickly becomes a star earner.

His roller-coaster journey eventually leads to the realisation that kids without predetermined or lucky opportunities, “have no reliable routes out of poverty” so they sell drugs and the like. But, “we are all the same. The difference is how rich our dads were…. you’re not better than us. It’s just two different games, from the very beginning. From birth.”

Stevenson has a neat turn of phrase, a good eye for detail, and a sense of humour. Interesting things happen in each chapter: forward drama is sustained, with character development, conflicts and transformation, providing ready ingredients to compel attention.

Around the time the book came out, Stevenson launched his YouTube channel, Gary’s Economics (1.5 million subscribers as of October 2025). A kind of public information service, the channel hosts his talks and interviews. People are taking notice. This is his introduction: “I’m Gary Stevenson. I made millions of pounds working in The City, betting inequality was going to destroy our economy. On this channel I’m going to explain what is really happening in the economy – what this means for you, and what you can do about it.”

Most of the explanations echo what he says in his book. He notes the impact of changes in high finance strategies over the years; how, for example, until 2008, interest-rate management (mainly, printing of more money by government) 1. conquered inflation; 2. ended boom and bust; 3. achieved sustained economic growth.

He writes: “By the beginning of 2011, it had become clear to me that the market was wrong. Not just the market, but the economists, the universities, the Monetary Policy Committee in the Bank of England, the news, the whole fucking shitshow…these guys blew the world up using nothing but mathematics, idiocy and hubris”

A sustainable economy for all no longer seemed to matter. He tries to figure it out: “All these governments were spending more than their income year after year, and their debts were growing.” Stevenson saw the same with ordinary people: “outgoings more than their income… For everybody losing money, there’s someone who’s gaining” (this rule, he says, defines a monetary system). Regarding houses and the stock market, he deduced: “we were the balance. We’re the boys who’d be richer than our fathers in a world of children who’d be poor…it wasn’t a crisis of confidence… It was inequality. Inequality that would grow and grow, and get worse and worse until it dominated and killed the economy that contained it. It wasn’t temporary; it was terminal… cancer.”

At the zenith of his success trading in billions, these thoughts drove him to some neurotic behaviour and physical illness. His discomfort deepened. He knew he needed to get out. But then his real troubles start, as he recounts:

“When Citibank paid me that huge bonus, the bonus that I can’t remember, at the beginning of 2012, they took care to tie me tight to my screens. Some of the bonus was to be paid up front, which was the money I was investing. The rest was to be paid with a significant delay. A quarter in 2013; a quarter in 2014; a quarter in 2015; a quarter in 2016. So you see, at that point, I could not really leave. The bank owed me over a million pounds. If I quit, I’d lose it all.”

He went to HR, hoping to leave to join a financial charity, as his contract seemed to permit. They indulged his hope, letting him apply, even though, “the paperwork package to leave and go to charity was enormous.”

In early 2013, he was called to a meeting with one of his managers, who only tightened the noose: “I’m afraid to tell you that the option is only possible with the approval of bank management. Bank management will not be giving approval.” In other words, you can leave but the money stays here, because his application was rejected. He remained trapped and humiliated. But he would not accept the suffocating conditions of his station. He went off sick. He got legal advice. He would play the long game and wear them out until they let him go with what he was owed. And after a year of constructive dismissal, hanging around being micromanaged yet paid to do nothing, they give in. He walks, bonus granted.

Near the end of the book, he looks back and wonders if he really outsmarted Citibank at all: “How do we ever know which of our wins, and which of our losses were from luck, and which ones were from skill?” Like trading. “I made money in 2011 and 2012, by betting on the collapse of the global economy, the slow but constant and certain collapse of living standards for ordinary people, for ordinary families, the descent of hundreds of millions of families across the world into inescapable poverty”

But then, “what do we do? Do we let it happen?… We can bet on the end of the world… we can all of us get rich from the end of the world, but not stop it, just watch it collapse.”

He excelled at bank gambling because he could accurately discern major societal trends, from how people were living, rather than from economic models others relied on. The tolerance of growing inequality is what concerns him. The link between income inequality and democratic erosion has been well established but little policy action taken to address it. John Cassidy, writer of Capitalism and Its Critics, saw that while academics usefully keep ideas alive, what drives social changes are material conditions and political movements, galvanised by crisis. One current obstacle is minimal labour organisation, even as signs of desire appear for more managed capitalism, in recognition of market limitations. Without strong government systems and international solidarity, democracy fails to thrive.

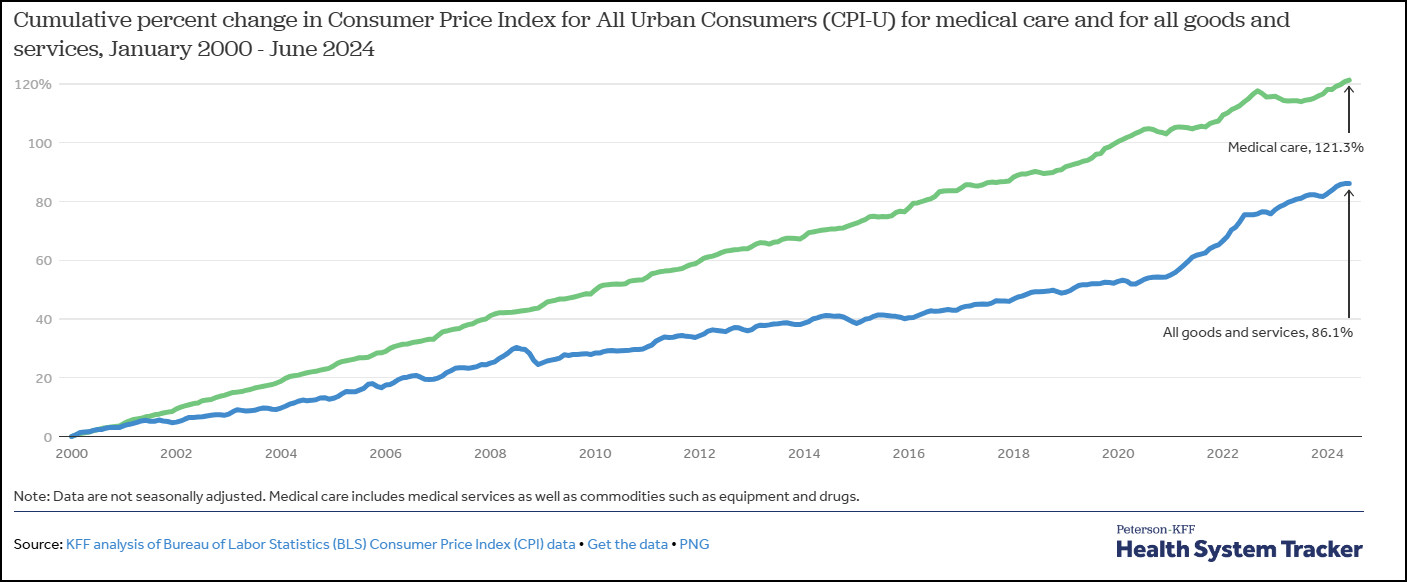

Inequality.org monitors America’s 100 largest low-wage corporations, CEO pay, and formerly illegal stock buybacks which have climbed since 2019, while median worker pay drops below U.S. inflation. Stevenson concluded that inequality was the winning trade. “The rich get the assets; the poor get the debt; and then the poor have to pay their whole salary to the rich every year just to live in a house. The rich use that money to buy the rest of the assets from the middle class; spending power disappears permanently from the economy; the rich becoming much richer and the poor…just die”

A good example of how private companies profit off human misery such as asylum-seeking, then dump on public services when funds dry up, appears anonymously, titled ‘Hotel Britannica’, in the April 2025 issue of Fence Magazine. Stevenson’s credible positions on these dystopian elements have gained as much traction as the likes of Farage, albeit with contrasting views and motives. Spending more on workers and the environment would mean less shareholder dividends and executive pay. Business Roundtables fight against benefitting other stakeholders. Ecological economists like Josh Farley chime with Stevenson’s detection of chinks in economic theory promises, whose actual outcomes include faster ecological collapse, public health declines, and increasing inequality and social disconnection. A framework prioritising ecological stewardship, cooperation, and well-being gains support.

In an overview of catastrophe risk, F. U. Jehn examines the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) report, “Hazards with Escalation Potential: Governing the Drivers of Global and Existential Catastrophes” (Stauffer et al., 2023), along with the WEF’s 2025 Global Risks Report. Inequality emerges as the key issue, very seriously influencing many other potential risks, while also primarily responsible for past crises. But the Global North seems intent on business as usual, and zero-sum logic, in reviving national industries and strengthening militaries, as if indifferent to exacerbated international fragmentation, and abandoning collective improvement of the global economic order. As Planet Critical’s Rachel Donald put it: “Most dangerous among us are those whose violence is permissible… because they are never forced to come face to face with those on whose backs they have built their kingdoms. Inequality has created societies where a minority are freed from the consequences of their actions.”

Ed Zitron uses terms like the Rot Economy and Shareholder Supremacy to convey inherent neoliberal selfishness. A critical tool proposed by the New Economics Foundation (NEF) is an extreme wealth line (EWL) – a metric or set of metrics which indicate the point at which extreme wealth concentration harms democracy, society, the economy, and the environment. This confronts the insidious role of extreme wealth in everyone’s quality of life, revises wealth norms, promotes fairer economics and policies including wealth taxation, as Rutger Bregman famously urged at Davos. Instead, with business as usual, wealth accumulation is rewarded by innumerable inducements, concessions and depreciation asymmetries. Reversing such perverse wealth transfers requires macroeconomic measurement reform to gauge actual wealth redistribution, and microeconomic policies to protect workers. This is the raison d’être of global campaigns like, End Austerity, comprising civil society organisations, trade unions, activists, and researchers calling to end austerity measures imposed by international financial institutions towards realising rights, development and social justice. For economically-hit deprived communities, Oxford professor Paul Collier narrows solutions down to devolved governance and serious long-term investment redistribution as top supports for people to get back on their feet.

In unpublished writings exploring ecology, Karl Marx imagined indigenous communism sustaining capitalist degrowth, to include community ownership, coops, mutual aid, and short work weeks, rather than sustainable development goals and green deals with growth imperatives. Instead of curbing transnational drivers of environmental degradation such as mining and cattle-ranching, offshore nature financing of conservation and carbon trading gives cover to opaque land and asset grabbing, where wealthy agents consolidate control over global impoverished labourers. Offshore: Stealth Wealth and the New Colonialism, Brooke Harrington’s book, inspects ‘the system’, the professional enablers who counsel the ultra-wealthy on ways to save and hide huge fortunes in secret offshore accounts.

On learning an RAF squadron was owned by a hedge fund, Craig Murray discovered how layers of subsidiary companies disguise ownership, and facilitate tax avoidance, and other forms of corruption, like consultancy contracts and associate directorships. Companies making unprecedented profits from manmade wars and famines, including Microsoft, Amazon & Google, are described by a 2025 UN report as a ‘joint criminal enterprise’. Time will tell if the writer about ‘necrocapitalism’, George Tsakraklides is correct in his evaluation of the Palestine conflict: “Palestine had to go because it wasn’t making anyone any serious money, like an employee given the boot with no notice. For capitalism, Palestine was yet another forest: its value could only be redeemed once it was turned into woodchip and casinos with a sea-view.” Writing of the crises which plague capitalism 177 years ago, Marx and Engels observed that “not only has the bourgeoisie forged the weapons that bring death to itself; it has also called into existence the men who are to wield those weapons — the modern working class.”

For a 2014 paper, political scientists reviewed 1,779 policy debates and found that preferences backed by popularity will never succeed if some elites did not approve as well. Legitimacy is defended with surveillance-heavy guard and spy labour, at the expense of services. Rob Larson’s book, Mastering The Universe, portrays the gratuitous largesse insisted on by the rich. In an enjoyable rant by Cory Doctorow, billionaires’ compulsions for personal sovereignty turns them into toddlers seething to avoid all normal constraints. Sociologist Steven Vass notes a 50-year trend in class inequality linked to social divisions, increased neglect of the common good, and political corruption. Neoliberal logic corporatises states. The journal, Environmental Science & Technology Letters, reports on mechanisms of entanglement embedded by vested interests through funding, data and executive functions, which influence public servants involved in protecting people and planet. This trap works better the more precarity becomes the workplace norm.

People trod on eventually say enough and at least try to reassert their primacy. Studying systemic criminality, Koenraad Priels insists on the need to go beyond policy reforms, and organise, with like-minded legal and human rights actors, for institutional and legal accountability, so as to litigate many state crimes, including elite impunity, ecocide, war racketeering, and institutional capture. He recently got the ball rolling by filing such a complaint at the ECHR, in the belief that, as the polycrisis was created by human choice, primarily by bankers and militaries, so can it be reversed, once gaping inroads into the pursuit of truth and the rule of law are plugged and repaired. Recent statements by Pope Leo establish him as adhering to his predecessor Francis’ convictions on the urgency of addressing social injustices and environmental destruction. Developing nations especially need to beware conditions for foreign capital promising globalisation benefits, as swapping sovereignty for dependence on such investment often forecloses preferred future possibilities in international trade and internal stability.

In her book, Reimaging Prosperity, Marija Bartl warns against competitiveness policies, which elicit anxiety and are unfair. Specialists Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson confirm their previous findings, as well as Stevenson’s thesis, that health, social and environmental crises are sustained by inequality, which itself has worsened. They too recommend wealth taxes, plus universal basic income, and truly democratic policymaking e.g. citizens’ assemblies. participatory budgeting. Feminist scholars in particular would restore commons as the most promising socio- political structure for instilling widespread cooperation, collective care, and just governance. An international collaboration working on clear proposals for deep systemic change that cannot be expected from insider power players, the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) aligns with a vision to target what Ray McGovern dubbed the MICIMATT (Military-Industrial-Congressional-Intelligence-Media-Academia-Think-Tank), to define interconnected sectors of influence on policy-making. Stevenson’s outreach to other concerned figures segues with this partnership model.

Critics have not neglected Stevenson, with media articles, especially one in the Financial Times, quoting former colleagues disputing his claims, but this clutching at straws pales in the headlights of his sincerity. He is a member of Patriotic Millionaires UK, who describe themselves as, ‘millionaires fighting inequality. To move money from the rich & create political economies where wealth does not mean power.’

He closes Trading Game with these lines: “I don’t know; I suppose games are like that. Sometimes you win and sometimes you lose. And, you know, what’s more important than winning? I don’t know. I can think of nothing.”

Fortunately. Gary Stevenson has thought a lot about what’s more important than the few winning, and is among those doing something about the gap.

Caroline Hurley is a Degrowther and Fallibilist, who lives in a sustainable community in rural Ireland. Her range of poetry, fiction, reviews and other non-fiction has featured in a variety of publications including Books Ireland Magazine, ZNetwork, Ireland’s Own Magazine, Arena Magazine (Au), Village Magazine, Dublin Review of Books, and elsewhere.

.jpg)