Though bruised and battered, the bond between Europe and the United States that has endured 80 uninterrupted years lives to see another day.

That was the message that visibly relieved European leaders conveyed at the end of an extraordinary week that brought the two sides of the Atlantic dangerously close to an all-out, calamitous trade war over the future of Greenland.

For a total of five days, Donald Trump kept the continent on tenterhooks with his shock threat to impose an additional 10% tariff on eight European countries, all NATO members, in an attempt to strong-arm the acquisition of the mineral-rich, semi-autonomous island that belongs to the Kingdom of Denmark.

"This Tariff will be due and payable until such time as a Deal is reached for the Complete and Total purchase of Greenland," Trump wrote in his now-infamous message.

The outrage was deafening. Presidents and prime ministers came forth in unison to support Denmark's sovereignty and denounce what they saw as blatant blackmail from a president intent on reshaping the global order according to his own vision.

"No intimidation nor threat will influence us," said French President Emmanuel Macron.

What followed that first wave of condemnations was a frantic race against the clock to convince Trump to abandon his annexationist agenda and salvage the transatlantic relationship – and to prepare to hit back should the worst come to pass.

EU ambassadors met on Sunday, the day after Trump's social media message, to begin preparations for 1 February, the day on which the 10% tariffs were due to take effect.

France took the lead by publicly calling for the activation of the Anti-Coercion Instrument, which would allow broad retaliation across multiple economic sectors. Originally designed with China in mind, the instrument has never been used – not even during last year's trade negotiations with the White House, when Trump continuously upped the ante to browbeat Europeans into wide-ranging concessions.

Donald Trump. Laurent Gillieron/ KEYSTONE / LAURENT GILLIERON

Back then, member states had been sharply split on how to respond, with France and Spain advocating an offensive, and Italy and Germany urging a compromise. But this time, it was different – drastically so.

Trump was no longer applying tariffs to rebalance trade flows and boost domestic manufacturing, the reasons he had cited on his "Liberation Day" in spring 2025. This time, he was seeking to apply tariffs to seize territory from an ally.

"Plunging us into a dangerous downward spiral would only aid the very adversaries we are both so committed to keeping out of our strategic landscape," Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, said in a speech in Davos. "So our response will be unflinching, united and proportional."

The unprecedented dimension of the challenge weighed heavily on capitals, which swiftly came to terms with the prospect of actual retaliation. It was a stark contrast from the political divisions and reservations that plagued the 2025 talks.

Diplomats in Brussels spoke of a collective determination to endure economic pain for the sake of defending Greenland, Denmark and the sovereignty of the entire bloc. A detailed list of tit-for-tat measures worth €93 billion was put on the table to be introduced as soon as Trump's additional duties entered into force.

In parallel, the European Parliament, enraged by Trump's ultimatum, voted to indefinitely delay the ratification of the EU-US trade deal, blocking the zero-tariff benefits for American-made products that von der Leyen and Trump agreed on in July.

Push and pull

And yet, as European leaders closed ranks and pushed back against Trump's expansionism, they also made it clear to everyone who was listening that diplomacy was their preferred option to keep the transatlantic alliance alive.

"We want to avoid any escalation in this dispute if at all possible," said German Chancellor Friedrich Merz. "We simply want to try to resolve this problem together."

Europeans began searching for an "off-ramp", as Finnish President Alexander Stubb aptly put it, to prevent a full-blown clash, safeguard Greenland and let Trump score a victory of sorts. Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni suggested that Trump might have misunderstood the purpose of the reconnaissance mission sent to the island, which he cited in his social post as justification for threatening the 10% tariff.

At first, the diplomatic overtures fell flat. Von der Leyen and Merz attempted to meet Trump in Davos, but despite rampant speculation, the bilaterals never took place. Meanwhile, Trump leaked a text message from Macron in which the French leader told him, "I do not understand what you are doing on Greenland"

The text, confirmed as authentic by a source in the French president's entourage, also pitched a G7 summit with "the Russians in the margins", a proposal that immediately raised eyebrows given Europe's common strategy to isolate the Kremlin internationally.

As tensions rose ever higher, Trump took the stage at the World Economic Forum and doubled down on his desire to take over Greenland, which he at times referred to as "Iceland".

"We want a piece of ice for world protection, and they (Europeans) won't give it," he told the packed room in Davos. "They have a choice: you can say 'yes' and we'll be very appreciative, and you can say 'no' and we will remember."

Yet Trump also said he did not want to use military force to accomplish his territorial designs, something which he had previously refused to rule out. The Europeans quickly caught on to the nuance and hoped that an opening was about to emerge.

The speech paved the way for NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte, who had kept a low profile in the spiralling crisis, to meet with Trump in Davos and strike what the two men called a "framework deal" to enhance security in Greenland and the entire Arctic region.

Giorgia Meloni and Mette Frederiksen. Geert Vanden Wijngaert/Copyright 2026 The AP. All rights reserved.

The agreement, details of which have not yet been made public and are subject to further discussions, was the "off-ramp" that allies were desperately looking for: Trump confirmed he would no longer apply tariffs or pursue the ownership of Greenland.

By the time EU leaders met in Brussels on Thursday for an emergency summit convened in reaction to the showdown, the atmosphere had shifted

Prime ministers were seen shaking hands and patting each other's backs with wide smiles on their faces. Upon arrival, they told reporters the transatlantic bond was too valuable to be ditched in one week.

The respite in the room was palpable, despite a sense of restlessness and confusion hanging in the air – and lingering fears that Trump's Greenland fixation might return.

"We remain extremely vigilant and ready to use our tools if there are further threats," Macron said, praising Europe's display of unity.

The morning after the late-night summit, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen met with Mark Rutte in Brussels and later flew to Nuuk to dispel the impression that the framework deal would be written without Danish or Greenlandic consent.

Whiplash

In a way, the chain of events ended as it started, with Europeans calling the US their closest ally and vowing to work together to confront global challenges.

But beneath the surface, a painful reckoning was underway.

Europeans have spent the last year scrambling to contain Trump's mercurial foreign policy, watching in disbelief as he floated business ventures with the Kremlin, sanctioned judges of the International Criminal Court, removed Nicolás Maduro from power in Venezuela, and expanded the Board of Peace ostensibly set up to manage post-war Gaza into a rival of the United Nations.

While those disruptive actions were, to a greater or lesser extent, tolerated, Trump's heavy-handed pursuit of Greenland proved to be too much to bear. For many, the tariff threat crossed a line and set a precedent, even if it was eventually withdrawn.

The whiplash from this turbulent week will not disappear.

As von der Leyen said, it will only amplify calls for a more independent Europe with a wider net of partners to fall back on.

"Everybody has drawn the conclusion that the relationship is on a different footing," said a senior EU official. "And that requires decisions on our side."

NATO, The EU, And Greenland: Alliance And

Security Implications In The Arctic –

Analysis

January 25, 2026

By Scott N. Romaniuk

US Focus Sharpens on Greenland

President Donald Trump’s renewed focus on Greenland, marked by escalating rhetoric and an increasingly assertive posture that challenges established norms of territorial sovereignty, has continued to thrust the Arctic into the centre of global politics. What initially seemed an offhand suggestion in August 2019—to purchase Greenland as a ‘large real estate deal’—has evolved into a major point of contention, exposing tensions among Washington’s ambitions, notions of American imperialism, alliance commitments, European security and sovereignty imperatives, and contours of great-power competition. Trump has framed Greenland as vital to US national security, citing concerns over Russian and Chinese activity in the region. Yet in doing so, he highlighted a paradox: the more aggressively the US administration seeks to secure its interests, the greater the risk of destabilising the region and straining the alliances that underpin its security.

Beyond the immediate diplomatic fallout, the Greenland debate raises a deeper and more uncomfortable question for Europe and the transatlantic alliance: what do European defence commitments and NATO’s collective-defence guarantees actually mean when pressure originates from within the alliance itself? Trump’s rhetoric forces allies to confront a theoretical but consequential dilemma—whether the political, legal, and normative assumptions underpinning NATO’s Article 5 and Europe’s own mutual-defence frameworks can withstand coercive behaviour by a leading ally. In doing so, Greenland becomes not merely an Arctic security issue, but a revealing measure for alliance cohesion, European strategic autonomy, and the credibility of collective defence in an era of intra-alliance tension rather than external attack.

Greenland and Iceland: Precedents in the North Atlantic

During the Second World War, the US established a presence on the island to prevent Nazi Germany from securing bases in the North Atlantic, thereby protecting critical shipping lanes. Greenland’s position, shaped by historical US military presence and enduring alliance frameworks, is therefore part of a broader pattern in North Atlantic security. A parallel precedent can be found in Iceland, where the US established diplomatic and military footholds during the Second World War after German forces occupied Denmark. Just as Greenland became critical during the Cold War and remains so today, Iceland shows how the US has balanced territorial sovereignty with alliance interests and Arctic security needs, illustrating the enduring tension between strategic necessity and multilateral cooperation in the North Atlantic.

The US Consulate in Reykjavik, led by Consul Bertil Eric Kuniholm, was officially opened on July 8, 1940, following his arrival on May 24. That same year, British troops landed in Iceland to preempt a German invasion, and Iceland sought US protection under the Monroe Doctrine—an initiative initially met with American caution. At the height of the Allied presence in late 1940, over 25,000 British and Canadian troops were stationed on the island. Ultimately, at British urging and following discussions between President Roosevelt and Icelandic Prime Minister Hermann Jónasson, American forces arrived in July 1941 to reinforce and eventually replace the British-Canadian military presence, marking the beginning of a permanent US diplomatic and security foothold in the North Atlantic

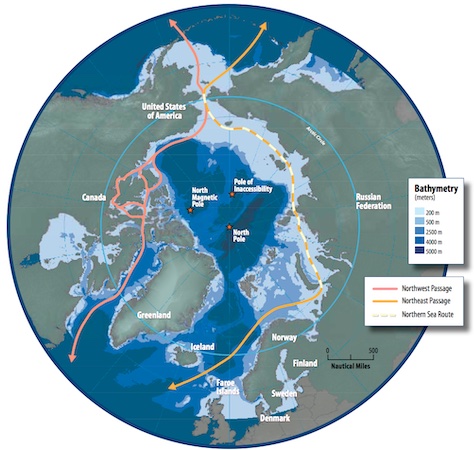

During the Cold War, Greenland became a key node in US early-warning architecture, monitoring Soviet missile activity and controlling access to the GIUK Gap—the maritime corridor between Greenland, Iceland, and the UK through which Soviet submarines could enter the Atlantic. The legal framework for US military presence was formalised in the 1951 US-Denmark Defense Agreement, granting the US the right to establish and operate bases while recognising Danish sovereignty. Subsequent bilateral arrangements and the Self-Government Act of 2009 expanded Greenlandic autonomy but left the provisions of the 1951 agreement largely intact. In 2023, the US and Denmark signed a Defense Cooperation Agreement (DCA), updating NATO frameworks for US forces in Denmark. As such, US operations in Greenland continue under a long-established legal and strategic framework, even as contemporary rhetoric can create the impression of extralegal ambition.

Today, Pituffik Space Base (renamed from Thule Air Base in 2023) is Greenland’s sole US military installation. Now staffed by 150 personnel—compared with roughly 10,000 American troops during the Cold War’s peak—the installation functions as a critical hub for missile warning, satellite surveillance, and Arctic monitoring on Greenland’s northwestern coast, across Baffin Bay from Nunavut, Canada. Sovereignty over Greenland remains unequivocally Danish, with all US military activity conducted under bilateral agreements that recognise Danish authority and regulate the construction and maintenance of facilities. Against this backdrop of established legal frameworks and alliance practice, Trump’s public musings about ‘taking’ Greenland represented a sharp departure from diplomatic convention and alliance norms.

The Security Dilemma at Play

Trump justified his interest in Greenland by invoking security threats from Russia and China, at times asserting that the island is heavily traversed by Russian and Chinese vessels—claims not supported by publicly available intelligence assessments—framing the issue in urgent terms and declaring, ‘Now it is time, and it will be done!!!’. These statements nonetheless reflect a familiar dynamic in international relations: the security dilemma. Actions taken by one state to enhance its own security can be perceived as threatening by others, prompting countermeasures that ultimately reduce overall stability.

Russia has expanded its Arctic capabilities, modernising northern bases, reinforcing its Northern Fleet, and asserting greater control over sea lanes. China, though not an Arctic state, has declared itself ‘Near-Arctic State’ and has invested in ports, research stations, and shipping infrastructure under its Polar Silk Road (PSR) initiative. A unilateral US move to assert control over Greenland could be interpreted in Moscow and Beijing as escalatory, accelerating militarisation rather than deterring it.

Allies and NATO: Tensions at the Core

Denmark responded firmly to Trump’s comments, reiterating that Greenland is Danish territory and that decisions regarding its future rest with Denmark and the people of Greenland. Danish officials also drew attention to a legal and political paradox within NATO. Article 5 obliges members to defend one another; in an extreme and highly unlikely scenario involving the use of force, alliance obligations could be thrown into contradiction.

While such a scenario remains theoretical, it points to a broader tension between unilateral ambition and alliance cohesion. European governments and international observers echoed concerns that the Arctic should remain a zone of co-operation rather than unilateral assertion, highlighting the fragility of trust even among close allies. This perspective was reflected decades earlier in his 1987 Murmansk speech, when Mikhail Gorbachev characterised the Arctic as a ‘peace and cooperation zone’, underscoring the long-standing emphasis on collaborative approaches in the region.

European and NATO Mutual-Defense Frameworks

European security is structured around overlapping mutual-defense obligations. The EU’s Mutual Defence Clause, introduced in 2009 under Article 42(7) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU, as amended by the Lisbon Treaty), obligates member states to provide ‘all the necessary aid and assistance’ if another member is the victim of armed aggression. It further specifies that Member States ‘shall act jointly in the spirit [emphasis added] of solidarity’, denoting a principle-based commitment rather than a rigid, legally prescribed obligation. This wording emphasises political and normative support while allowing flexibility in how assistance—military, humanitarian, logistical, or intelligence—is provided.

The clause also accommodates states with longstanding policies of neutrality, such as Austria and Ireland, which can participate in cooperative security measures without engaging directly in combat. Finland and Sweden, historically considered ‘neutral’ despite their contingent wartime alignments and Cold War security positions, joined NATO in April 2023 and March 2024, respectively, marking a shift in their security posture while maintaining engagement with EU cooperative frameworks. In practice, Article 42(7) has never been tested in a large-scale interstate conflict, leaving its operational scope and political consequences largely theoretical despite its symbolic and deterrent value.

NATO’s Article 5, in contrast, establishes that an attack against one ally is considered an attack against all, forming the bedrock of collective defence in the Euro-Atlantic area. Yet Article 5 has been formally invoked only once, following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 (9/11), and has never been applied in response to a conventional armed attack on alliance territory. As a result, while both Article 5 and Article 42(7) function as powerful political messages intended to deter aggression, their precise legal and operational implications in a high-intensity conflict remain subject to interpretation and political discretion. These frameworks are complemented by initiatives such as the EU’s Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), which seeks to enhance interoperability and integrated planning among European militaries.

Within NATO’s own treaty framework—the North Atlantic Treaty, or Washington Treaty—the US’ stated threats regarding a potential Greenland takeover appear inconsistent with several core obligations. Article 1 commits members ‘to settle any international dispute in which they may be involved by peaceful means… and to refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force’, a standard that such rhetoric appears to undermine. Article 2 further requires that ‘The Parties will contribute toward the further development of peaceful and friendly international relations’, an obligation difficult to reconcile with coercive statements directed at allied territory. Article 6 makes clear that collective defence under Article 5 applies only to an ‘armed attack… on the territory of any of the Parties’, meaning Greenland cannot credibly be framed as a defensive trigger within NATO’s own legal definitions. Article 7 underscores that the US, as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, carries a special responsibility ‘for the maintenance of international peace and security’, while Article 12 reiterates the obligation to pursue the ‘maintenance of international peace and security’, further highlighting the tension between treaty commitments and takeover threats.

In the context of Greenland, these arrangements introduce a complex legal and strategic judgement. Although Greenland is Danish territory, its international alignments differ from Denmark’s own: Greenland is institutionally part of NATO through Denmark’s membership and is part of the Council of Europe, covered by Denmark’s membership, but it is not part of the EU. As such, the extent of allied involvement in a crisis would depend on how a threat is defined, whether it falls within NATO or other institutional competencies, and the prevailing view that Greenland’s geographic distance means it remains primarily Denmark’s responsibility.

This ambiguity raises the question of whether Greenland can be considered an internal EU security matter. On one hand, Greenland’s constitutional link to an EU member state, its position in the Arctic, and its relevance to EU interests in areas such as resilience, critical infrastructure, climate security, and supply chains suggest that developments affecting Greenland may have indirect implications for the Union’s internal security environment. On the other hand, Greenland’s status outside the EU, its extensive autonomy, and the predominance of national and NATO competencies in defence and territorial security argue against classifying it as an internal EU security issue, instead situating it within the domain of external security and allied cooperation.

Canada: The Silent Arctic Stakeholder

For the most part, Canada’s response has been restrained, offering only that Ottawa is ‘concerned’ about Trump’s tariffs on European countries and growing assertiveness towards Greenland. In his recent Davos speech, Prime Minister Mark Carney stressed that Greenland’s future is a matter for Copenhagen and Nuuk alone, firmly backing Danish sovereignty and reiterating support for international norms regarding territorial integrity—a stance widely seen as a principled defence of alliance solidarity and the rules-based order in the Arctic. At the same time, Carney framed the broader international system as being in a state of ‘rupture,’ noting that middle powers must build new coalitions because great powers increasingly use economic and strategic influence as coercion. This implicit critique highlights the limits of existing alliance structures and Canada’s constrained leverage in shaping security outcomes around Greenland.

As European nations deploy small numbers of troops to Greenland, Carney has considered a similar, symbolic contribution—likely minimal. By comparison, Canada’s participation in Operation Prosperity Guardian in response to Houthi attacks in the Red Sea involved only a few staff officers and an intelligence analyst. As an Arctic nation, NATO member, and close US ally with northern security interests, Ottawa has largely adhered to general statements emphasising international law, sovereignty, and alliance commitments, without overt condemnation or visible diplomatic mobilisation.

This caution reflects Canada’s preference for quiet diplomacy, reinforced by deep integration with US defence structures through the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), longstanding Arctic cooperation, and a desire not to upset its close relations with Washington. Yet Ottawa’s muted posture introduces ambiguity. Unlike Denmark’s clear stance, Canada’s restraint underscores the uneven ways allies show dissent or acquiescence within NATO, raising questions about collective messaging and cohesion in the Arctic.

The Risks of Greenlandic Independence

The issue of Greenland’s potential independence will also require revisitation once the outlines of alliance obligations are clearer. Trump’s statements questioning Denmark’s historical claim to the island suggest that he might similarly withhold recognition of an independent Greenland, creating a potential diplomatic and legal grey zone. Aside from recognition issues, a newly independent Greenland could be exposed to acute vulnerabilities: it lacks the military resources, infrastructure, and capacity to defend itself in a region increasingly militarised by great powers. Independence without reliable security guarantees can leave the island exposed to coercion, foreign influence, or opportunistic actions, meaning that sovereignty in the Arctic entails more than formal political status.

Possible Paths Forward

The Greenland debate can be framed through several broad, illustrative scenarios. Each scenario reflects not only geopolitical choices but also the constraints and uncertainties introduced by overlapping EU and NATO obligations, whose precise operational scope remains largely untested.Diplomatic Expansion of Access

In this scenario, the US seeks expanded military or infrastructural access through negotiation rather than sovereignty claims. Danish and Greenlandic authority remains intact, and objectives are partially met. NATO and EU frameworks—while largely theoretical in their application to Greenland—serve as political and legal cues, reinforcing alliance cohesion without triggering formal obligations. Russia and China would likely monitor developments closely but refrain from dramatic escalation.

Unilateral Annexation or Seizure

A hypothetical attempt to seize or annex Greenland represents the most destabilising outcome. Legal ambiguities under Article 5 NATO and Article 42(7) TEU could complicate allied responses: Article 5 has only been invoked once (post-9/11), while Article 42(7) remains theoretical in practice. Such a move would almost certainly strain NATO and EU political coordination, accelerate Russian and Chinese Arctic militarisation, and undermine global sovereignty norms.

Symbolic Threat Without Action

Even absent concrete measures, repeated rhetorical threats regarding Greenland can alter behaviour. Denmark may feel pressured to grant limited concessions, allies may grow uneasy, and external powers could justify expanding their Arctic initiatives in response. In this context, NATO and EU frameworks act more as political deterrents than legally enforceable guarantees, highlighting the distinction between formal obligations and their practical application.

Incremental Influence Through Investment

Rather than formal military access or annexation, influence could be pursued through economic, scientific, or infrastructure projects. Over time, these initiatives could shift local leverage and alignment without triggering formal alliance obligations, reflecting how legal frameworks serve as markers rather than strict operational mandates.

Multilateral Arctic Cooperation

Greenland’s role could evolve within a coordinated multilateral framework involving Denmark, the US, Canada, and other Arctic nations. EU and NATO instruments, while largely theoretical in application to Greenland, provide a reference point for cooperation, interoperability, and shared intent. Joint research, coordinated military presence, or climate and security initiatives could strengthen regional governance and reduce unilateral tensions.

Local-Led Autonomy or Policy Shift

Greenland might assert stronger self-determination, negotiating terms directly with multiple powers. This could involve partnerships with non-Western states or alternative defence arrangements, creating a more complex geopolitical environment. EU and NATO frameworks would remain largely advisory, offering political guidance but limited enforceable authority, emphasising Greenland’s primary reliance on Denmark and alliance consensus.

Crisis-Driven Escalation

A security incident, environmental disaster, or resource dispute could trigger rapid involvement by multiple powers. In such a scenario, the untested nature of Article 5 and Article 42(7) would leave allied responses uncertain, highlighting the gap between treaty obligations and practical coordination. Outcomes would depend on political will, diplomatic agility, and the ability of Denmark and allies to manage escalation while preserving broader alliance cohesion.

Greenland, Great-Power Competition, and Arctic Security

The Greenland dilemma illustrates the Arctic’s shifting power dynamics. Russia increasingly treats the region as central to its security and economic strategy, while China positions itself as a key Arctic stakeholder through investment and scientific engagement. US rhetoric hinting at unilateral control risks pushing Moscow and Beijing toward closer alignment, reinforcing rather than mitigating competitive pressures.

Public discussion of annexation by a major power carries implications beyond Greenland. History shows that claims of necessity have been used to justify violations of territorial sovereignty—from Crimea and Ukraine to maritime disputes in the South China Sea—and other contested territories, such as Western Sahara, Northern Cyprus, the Golan Heights, and Nagorno-Karabakh, demonstrate how unilateral control can persist despite legal challenges. Greenland differs fundamentally: it is peaceful, allied, and largely self-governing. Yet precedent matters.

Arctic Security: What Next?

Discussions of long-term Arctic security frequently focus on NATO integration, infrastructure investment, and multilateral exercises. As the Arctic becomes more contested, regional stability—and the wider international order—hinges on how states project intent, exercise influence, and respect cooperative frameworks. Greenland demonstrates that even among allies, misjudged displays of power can undermine trust, provoke countermeasures, and destabilise what should be a zone of managed, predictable security.

Trump’s assertive posture has now prompted European allies to shift from passive security dependence toward a more active, even proactive, approach regarding territory associated with a European state. Recent events highlight a paradox: Trump has portrayed Greenland as threatened by Russia and China and framed its security as a national imperative for Washington, yet European deployments—intended to bolster security—have done little to temper those claims. Crucially, deployments have strengthened Greenland’s defence not against Russia or China, but rather in a posture directed at their own ally.

At its core, Greenland’s wider importance shows just how tricky it is to balance national ambitions, alliance commitments, and working together with other countries in the Arctic—a region where strategic interests, cooperation, and rivalry all collide. US interest underscores the enduring geostrategic value of the island, yet NATO and EU frameworks—while providing important political and legal guidance—remain largely untested in practice, leaving response and coordination contingent on political will. Stability in the Arctic will hinge not on unilateral ambition, but on careful diplomacy, coordinated multilateral action, and respect for established norms — ensuring Greenland remains a secure and predictable cornerstone of transatlantic and Arctic security.

Scott N. Romaniuk

Dr. Scott N. Romaniuk is a Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Contemporary Asia Studies, Corvinus Institute for Advanced Studies (CIAS), Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungary.