It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Thursday, January 02, 2020

Sunday, July 05, 2020

Algeria buries fighters whose skulls were in Paris museum

A soldier and members of the Algerian Republican Guard, guard the remains of 24 Algerians at the Moufdi-Zakaria culture palace in Algiers, Friday, July, 3, 2020. After decades in a French museum, the skulls of 24 Algerians decapitated for resisting French colonial forces were formally repatriated to Algeria in an elaborate ceremony led by the teary-eyed Algerian president. The return of the skulls was the result of years of efforts by Algerian historians, and comes amid a growing global reckoning with the legacy of colonialism. (AP Photo/Toufik Doudou)

MORE PICTURES

https://apnews.com/695349764cae2a309c6d4ca82cbdd35a

ALGIERS, Algeria (AP) — Algeria at last buried the remains of 24 fighters decapitated for resisting French colonial forces in the 19th century, in a ceremony Sunday rich with symbolism marking the country’s 58th anniversary of independence.

The fighters’ skulls were taken to Paris as war trophies and held in a museum for decades until their repatriation to Algeria on Friday, amid a growing global reckoning with the legacy of colonialism.

Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune said he’s hoping for an apology from France for colonial-era wrongs.

“We have already received half-apologies. There must be another step,” he said in an interview broadcast Saturday with France-24 television. He welcomed the return of the skulls and expressed hope that French President Emmanuel Macron could improve relations and address historical disputes.

Tebboune presided over the interment of the remains Sunday in a military ceremony at El Alia cemetery east of Algiers, in a section for fallen independence fighters. Firefighters lay the coffins, draped with green, white and red Algerian flags, in the earth.

The 24 took part in an 1849 revolt after French colonial forces occupied Algeria in 1830. Algeria formally declared independence on July 5, 1962 after a brutal war.

Algeria’s veterans minister, Tayeb Zitouni, welcomed “the return of these heroes to the land of their ancestors, after a century and a half in post-mortem exile.”

Algerians from different regions lined up to pay respect to the fighters on Saturday, when their coffins were on public display at the Algiers Palace of Culture.

Mohamed Arezki Ferrad, history professor at the University of Algiers, said hundreds of other Algerian skulls remain in France and called for their return, as well as reparations for French nuclear tests carried out in the Algerian Sahara in the early 1960s.

Thursday, November 13, 2025

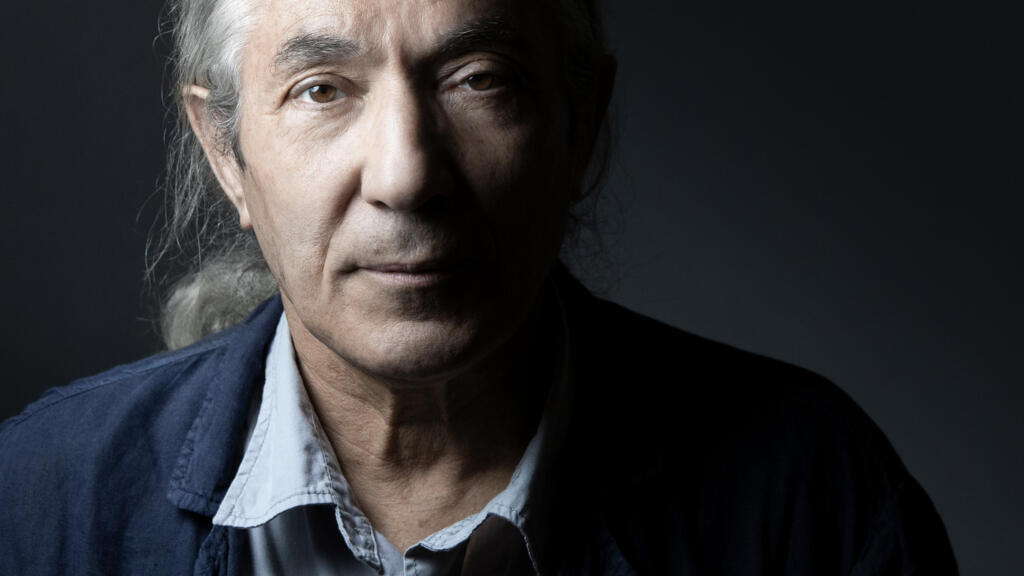

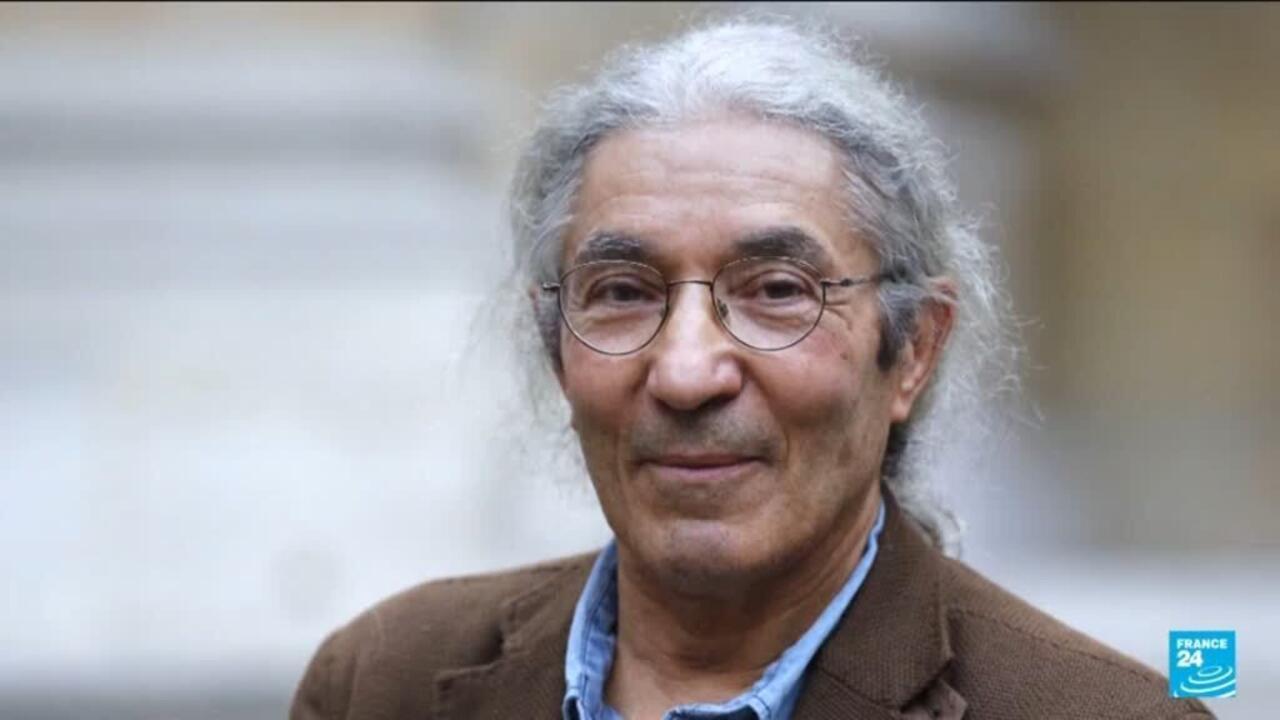

Algeria frees French-Algerian writer Boualem Sansal for transfer to Germany

Algeria has pardoned French-Algerian writer Boualem Sansal after a request from Germany, to where he will be transferred for medical treatment after a year in detention, it was announced Wednesday.

Issued on: 13/11/2025 RFI

After German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier on Monday urged Algeria to free the 81-year-old, "the president of the republic decided to respond positively", the Algerian presidency said.

The statement said Germany would take charge of the transfer and treatment of Sansal, who has prostate cancer, according to his family.

Sansal was given a five-year jail term in March, accused of undermining Algeria's territorial integrity after he told a far-right French outlet last year that France had unjustly transferred Moroccan territory to Algeria during the 1830 to 1962 colonial period.

France 'concerned' over disappearance of writer Boualem Sansal in Algeria

Algeria views those ideas - which align with longstanding Moroccan territorial claims - as a challenge to its sovereignty.

He was arrested in November 2014 at Algiers airport. Because he did not appeal March's ruling, he was eligible for a presidential pardon.

Steinmeier urged Algeria to make a humanitarian gesture "given Sansal's advanced age and fragile health condition" and said Germany would take charge of his "relocation to Germany and subsequent medical care".

'Mercy and humanity'

French President Emmanuel Macron had also urged Tebboune to show "mercy and humanity" by releasing the author.

Sansal's daughter Sabeha Sansal, 51, told Ffrench news agency AFP by telephone from her home in the Czech Republic of her relief.

"I was a little pessimistic because he is sick, he is old, and he could have died there," she said. "I hope we will see each other soon."

A prize-winning figure in North African modern francophone literature, Sansal is known for his criticism of Algerian authorities as well as of Islamists.

He acquired French nationality in 2024.

Appearing in court without legal counsel on June 24, Sansal had said the case against him "makes no sense" as "the Algerian constitution guarantees freedom of expression and conscience".

When questioned about his writings, Sansal asked: "Are we holding a trial over literature? Where are we headed?"

French-Algerian writer Boualem Sansal sentenced to five years in prison

His case has become a cause celebre in France, but his past support for Israel and his 2014 visit there have made him largely unpopular in Algeria.

The case has also become entangled in the diplomatic crisis between Paris and Algiers, which has led to the expulsion of officials on both sides, the recall of ambassadors and restrictions on holders of diplomatic visas.

Another point of contention was the sentencing to seven years in prison of French sportswriter Christophe Gleizes in Algiers on accusations of attempting to interview a member of the Movement for the Self-Determination of Kabylie (MAK), designated a terrorist organisation by Algeria in 2021.

Both Sansal and Gleizes's prosecution came amid the latest rise in tensions between Paris and Algiers, triggered in July 2024 when Macron backed Moroccan sovereignty over the disputed Western Sahara, where Algeria backs the pro-independence Polisario Front.

Civil servant turned novelist

An economist by training, Sansal worked as a senior civil servant in his native Algeria, with his first novel appearing in 1999.

"The Barbarians' Oath" dealt with the rise of fundamentalist Islam in Algeria and was published in the midst of the country's civil war which left some 200,000 people dead according to official figures.

He was fired from his post in the industry ministry in 2003 for his opposition to the government but continued publishing.

Algeria court upholds writer Boualem Sansal's five-year jail term

His 2008 work "The German Mujahid" was censored in Algeria for drawing parallels between Islamism and Nazism.

He has received several international prizes for his work, including in France and Germany.

In recent years Germany has offered refuge to several high-profile prisoners from other countries.

The late Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny was treated at Berlin's Charite hospital after being poisoned in August 2020.

Last year Germany welcomed several other high-profile Russian dissidents as part of a historic prisoner swap with Moscow.

(with newswires)

Algeria’s president on Wednesday granted a humanitarian pardon to French-Algerian novelist Boualem Sansal following a German request for his release. The 81-year-old writer, whose year-long imprisonment sparked widespread criticism, arrived in Berlin late Wednesday for medical treatment.

Issued on: 12/11/2025 -

By: FRANCE 24

French-Algerian writer Boualem Sansal was granted a humanitarian pardon, the Algerian presidential office said in a statement on Wednesday.

Sansal, 81, was arrested on November 16, 2024, in Algiers and sentenced on appeal in July 2025 to five years in prison for comments deemed harmful to national unity.

His pardon came after German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier urged Algeria to free Sansal. "The president of the republic decided to respond positively to the request of the esteemed president of the friendly Federal Republic of Germany", said the Algerian presidential statement.

READ MOREFrench-Algerian writer Boualem Sansal won't appeal sentence, hopes for pardon

Steinmeier thanked Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune in a statement for the "humanitarian gesture" that "demonstrates the quality of the relations and trust between Germany and Algeria".

Hours after the pardon was announced, Sansal arrived in Berlin, according to the German presidential office.

French President Emmanuel Macron on Wednesday thanked his counterparts in Algiers and Berlin for Sansal's release on humanitarian grounds.

Macron, while visiting the southern city of Toulouse, said he had spoken by phone with Steinmeier "to express my deep gratitude for Germany's good offices", after Berlin requested and obtained Boualem Sansal's pardon.

"I acknowledge this gesture of humanity from President Tebboune and thank him for it," he said of the Algerian leader, adding that he remained "available to discuss with him all matters of interest to our two countries".

Prior to the pardon, Macron had called on Tebboune to show "mercy and humanity" by releasing the author.

READ MOREMacron urges 'mercy' for jailed writer Sansal in call with Algeria's Tebboune

Sansal is known for his criticism of Algerian authorities as well as of Islamists. He was arrested in November after saying, in an interview with a far-right French media outlet, that France unfairly ceded Moroccan territory to Algeria during the colonial era.

His statement, which echoed a long-standing Moroccan claim, was viewed by Algeria as an affront to its national sovereignty.

The author's arrest in Algiers deepened a diplomatic rift with France, which analysts have said is the worst the two countries have seen in years.

04:16

'I hope we will see each other soon'

Sansal's daughter Sabeha Sansal, 51, expressed her relief over the decision in a phone call from her home in the Czech Republic.

"I was a little pessimistic because he is sick, he is old, and he could have died there," she said. "I hope we will see each other soon."

A prize-winning figure in North African modern francophone literature, Sansal acquired French nationality in 2024.

Appearing in court without legal counsel on June 24, Sansal had said the case against him "makes no sense" as "the Algerian constitution guarantees freedom of expression and conscience".

When questioned about his writings, Sansal asked: "Are we holding a trial over literature? Where are we headed?"

His case has become a cause celebre in France, but his past support for Israel and his 2014 visit there have made him largely unpopular in Algeria.

The case has also become entangled in the diplomatic crisis between Paris and Algiers, which has led to the expulsion of officials on both sides, the recall of ambassadors and restrictions on holders of diplomatic visas.

READ MORE'Insult to injury': What’s behind the rising tensions between France and Algeria?

Another point of contention was the sentencing to seven years in prison of French sportswriter Christophe Gleizes in Algiers on accusations of attempting to interview a member of the Movement for the Self-Determination of Kabylie (MAK), designated a terrorist organisation by Algeria in 2021.

Both Sansal and Gleizes's prosecution came amid the latest rise in tensions between Paris and Algiers, triggered in July 2024 when Macron backed Moroccan sovereignty over the disputed Western Sahara, where Algeria backs the pro-independence Polisario Front.

Civil servant turned novelist

An economist by training, Sansal worked as a senior civil servant in his native Algeria, with his first novel appearing in 1999.

"The Barbarians' Oath" dealt with the rise of fundamentalist Islam in Algeria and was published in the midst of the country's civil war which left some 200,000 people dead according to official figures.

He was fired from his post in the industry ministry in 2003 for his opposition to the government but continued publishing.

His 2008 work "The German Mujahid" was censored in Algeria for drawing parallels between Islamism and Nazism.

He has received several international prizes for his work, including in France and Germany.

In recent years Germany has offered refuge to several high-profile prisoners from other countries.

The late Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny was treated at Berlin's Charite hospital after being poisoned in August 2020.

Last year Germany welcomed several other high-profile Russian dissidents as part of a historic prisoner swap with Moscow.

(FRANCE 24 with AFP)

Friday, June 28, 2024

After fighting for its independence, the country exported its ideology — and arms — across the continent

“The Algerian army made me a man,” declared Nelson Mandela as soon as he landed in Algiers on May 16, 1990, choosing the country that had introduced him to armed resistance as his first stop on his diplomatic tour after being released from prison in South Africa. Barely out of the plane and still inside Boumediene Airport, the revolutionary figure spoke of the influential time he spent in the training camps of the Algerian National Front of Liberation (FLN) in 1962, where, alongside fighters from the FLN’s armed wing, he learned about the ideology — and practicalities — of leading a war of liberation. Mandela would reflect fondly on his time with the FLN in his 1994 memoir, “Long Walk to Freedom,” despite it being the main reason he would be branded as a “terrorist” when arrested and sent to prison that summer.

Mandela’s recollection of Algeria’s support for the African National Congress (ANC) testified to the crucial but forgotten role the country played in Africa’s decolonization throughout the 1960s. At the start of the decade, the newly born North African state was signing its independence after winning what The New York Times called “the cruelest colonial war of the modern epoch.” As many as 1.5 million Algerians died in the eight-year conflict, instigated by the FLN with independence as its central aim. The war itself was riddled with guerrilla warfare and war crimes; the political turmoil it caused in France forced the undoing of the Fourth Republic.

But the successful armed struggle for independence enabled Algeria to position itself as the spearhead of African liberation and the champion of pan-African unification. A foreign policy focused on providing material and political support to every African liberation movement propelled Algeria to the forefront of a nascent postcolonial order overflowing with optimism and idealism for a new Africa — free, anticolonial and revolutionary.

“Well before we won independence, our country was conscious of its responsibility toward the peoples engaged in struggles against colonialism like we were,” Ahmed Ben Bella declared in his first public address as prime minister of the independent state of Algeria during the Nov. 1, 1962, celebrations held to mark the anniversary of the FLN’s insurrection. His speech was punctuated by thunderous troops marching, the sheer number of which garnered a telling comment from Tunisia’s foreign minister: “There are arms enough in this country to supply all of Africa.”

Within a year, Ben Bella had successfully supplied such cross-continental material support. His first action was to transform Algiers into a host city welcoming any liberation movement, guerrilla group, anti-fascist organization, opposition party or exiled revolutionary seeking refuge, training or help. By the end of 1963, more than 80 organizations found safe haven in the capital city, including representatives from colonized countries across the continent: Namibia seeking independence from Germany; South Africa from Dutch settlers; and Angola, Mozambique and Cape Verde from Portugal. All were given villas and official buildings — vacated by the French a year prior — to live in and work from, a monthly stipend and passports to travel to international conferences for diplomatic work, as well as weapons and supplies to train their militants. Seven hundred South African freedom fighters were training in Algerian camps to learn the FLN’s guerrilla-style warfare, 60 Congolese cadres were interning in the FLN’s government to learn about revolutionary politics, and all officers from the Canary Islands’ independence movement were training in Algerian military schools.

The capital city that had been destroyed by French troops during the 1957 Battle of Algiers was now sheltering every aspiring revolutionist and exiled militant. In its streets brewed radical, subversive theories and hope for a new order led by a free, united Africa. Stephane Hessel, a French diplomat stationed in Algiers, would explain this utopia in his memoir: “Dissidents from every authoritarian regime in the Southern Hemisphere flocked to Algiers to devise the ideology that came to be known as ‘Third Worldism.’ It rejected the inertia of Western civilization and counted on the new youth of the world, who sought to liberate themselves once and for all.”

Home to some of the most famous revolutionary fronts in the world, from the ANC to the Black Panthers, Algiers was baptized the “Mecca of Revolution” in 1967 by Guinean nationalist militant Amilcar Cabral who, speaking with a journalist, declared: “Take your pens and write: Muslims go on pilgrimage to Mecca, Christians to the Vatican, revolutionaries to Algiers.”

Algeria’s bloody efforts to wrench itself from French control became a clarion call to so many movements, which saw their own struggle reflected in its fight for independence. “The situation in Algeria was the closest model to our own,” wrote Mandela in his memoir, “in that the rebels faced a large white settler community that ruled the indigenous majority.”

Algeria’s unwavering dedication to African liberation followed its 132-year struggle against French occupation and colonization. In 1830, France invaded Algiers to distract public opinion from the failing Bourbon monarchy and a divided, roiling country. After 41 years of war, France declared Algeria a metropolitan department, reducing natives to second-class subjects devoid of any citizenship status while French settlers moved en masse to what they deemed their new territory. The resulting order was upended when the FLN launched a series of violent attacks across Algeria on Nov. 1, 1954, after decades of thwarted legal resistance.

The seed of Algeria’s radical solidarity with other colonized states was planted during the next seven years of war by the FLN’s prime theorist, Frantz Fanon, an Afro-Caribbean former psychiatrist living in Algiers. Fanon, who was born in the French overseas department of Martinique, had been responsible for the psychiatric care of patients distressed by the French army’s routine use of torture and the consequences of a century of subjugation. He used the Algerian experience to theorize liberation: To him, Algeria was demonstrating to the world that independence could be seized only by force, never gifted.

To publicize the Algerian cause across Africa, Fanon led the FLN’s delegation to join heads of African nations at the All-African Peoples’ Conference, hosted by Ghana, in 1958. There, he included Algeria in a long list of African countries choked by the hand of Euro-American imperialism. Fanon upheld Algeria as a “guide territory” where “the rot of the [colonial] system … the defeat of racism and the exploitation of man” was at stake. In his 1964 book, “Toward the African Liberation,” he eloquently described the FLN’s pan-African mission: “Having carried Algeria to the four corners of Africa, we shall return with all of Africa towards African Algeria, towards the north, towards Algiers, continental city, and launch a continent upon the assault of the last rampart of colonial power.”

By the time independence was declared, the FLN’s liberating action against a colonial state, which had reportedly displaced 2 million Algerians into surveillance camps and killed 1 million people, had won the country admiration, moral authority and a long list of supporters among African heads of state. Because Algeria had gained recognition as the first African country to win its independence by means of force, it became natural for the FLN to advocate for the country’s responsibility to help other African nations win back their freedom.

In every speech, Ben Bella would highlight Algeria’s “duty toward our African brothers,” defining brotherhood not by blood or ethnicity but by degree of revolutionary zeal and the commonality of a history of suffering under colonialism. “The Africans expect a great deal from us. We cannot let them down,” Ben Bella stated in a public address, explaining that “Africanism [is] deeply embedded in the [Algerian] popular consciousness.”

To achieve Africa’s unity, mending the ideological divide that split the continent was a first necessity. While radical states like Algeria, Sudan, Congo-Brazzaville and Guinea believed in a pan-African project achieved through revolutionary means, more conservative states still had ties to Western governments and were distrustful of revolutionary rhetoric. To rally them, Algeria promoted the use of force as a tool of liberation. As ardent defenders of armed resistance, the FLN argued for the necessity of violence as underlined by Fanon in his final study of the Algerian war, “The Wretched of the Earth”: Occupation being a violent phenomenon imposed through violent means, the colonized had no choice but to take back the initial violence and force it upon the occupying powers in order to break it.

Through Fanon’s philosophy, the FLN successfully rallied supporters of nonviolent resistance to its cause, like Ghanaian Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah, whose commitment to nonviolence dwindled after the FLN’s visit in 1958. Similarly, following his initial time in Algeria, Mandela concluded that “South Africa ruled by the gun could only be liberated with use of force,” despite years of having believed that peaceful liberation was possible. Colonialism “understands only the language of force and violence,” Ben Bella would explain. “We tell our South African brothers that hunger strikes and demonstrations will get you nowhere.”

With the African political limelight increasingly occupied by radical states, the continental city of Algiers established as the mecca of revolutionaries, and the FLN military camps full of African resistance figures, the pan-African unity and revolutionary solidarity Algeria had dreamed of leading was taking shape. One event in April 1963 would propel it to greater heights — the creation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU). The new intergovernmental institution was the first of its kind, designed as a continental equivalent to the United Nations, free from Western influence and oversight.

A month later, the largest African Union festival was organized to celebrate the founding of the OAU, which opened its doors in Addis Ababa. The choice of Ethiopia as a host was immensely symbolic: It was the only country in attendance that was never under the yoke of colonialism. The festival welcomed 32 African countries and upheld culture and art from every corner of the continent to give concrete expression to African unity and identity.

There, Algeria took the stage, front and center, and for Ben Bella, it was time to talk of blood. “We have spoken of a development bank. Why haven’t we spoken of a bank of blood to come to the aid of those who are fighting in Angola and elsewhere in Africa?” the Algerian president declared in one of his many flamboyant speeches. “We have no right to think of eating better when people fall in Angola, Mozambique, in South Africa. But we have a ransom to pay. We must accept to die together so that African unity does not become a vain word.” He continued, “Let us all agree to die a little … so that the people still under colonial rule may be free.”

Impassioned and charismatic, Ben Bella never missed an opportunity to take the mic and call for collective responsibility. Yet his enthusiasm was not without a patronizing tone and risked giving rise to a cult of personality. Struck by the talk of martyrdom and the belligerent imagery conjured, one attending journalist recorded, “I do not think that I have ever had such a profound sense of African unity as when I listened to Ben Bella, tears in his eyes, visibly moved, urging his listeners to rush to the assistance of the men dying south of the equator.”

Melodramatic as they were, the speeches from the Algerian contingent did produce tangible measures — the OAU festival concluded with the creation of a Liberation Committee and an African Battalion tasked to come to the aid of revolutionary and liberation movements in need of weapons, money or militants. The committee’s role was to coordinate support among states and consolidate newly won independence by fostering cooperation across the continent.

Through the committee, Algeria started to advocate for African solutions to African problems. In 1963, Ben Bella blocked British military aid meant to be sent to Tanganyika (now Tanzania) to resist armed mutiny and provided arms to Prime Minister Julius Nyerere instead. The goal was to maintain sufficiency within the continent and avoid being indebted to the West.

While Ben Bella rebuked Western states for their interventions in Africa, he did not hesitate to come to the aid of Latin American and Middle Eastern movements. He defied the embargo to meet with Cuba’s Fidel Castro, welcomed a delegation of the Venezuelan National Liberation Front, inaugurated an embassy and an African-American center for the Black Panthers in central Algiers, and opened the first office abroad for Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat’s Fatah.

These actions quickly attracted the ire of the American press. To The New York Times, Ben Bella was bordering on hubris — the paper painted Algeria as being “proud to the point of arrogance,” criticizing the government’s constant need to “meddle in the affairs of others.” The criticism did not stop Algeria from continuing to export its support for radical movements internationally, choosing to let its diplomatic ties with America and Britain fray and leaning toward non-Western countries instead. It was a decisive choice in the context of a Cold War that drew lines between pro-Soviet and pro-Western blocs.

But transnational revolutionary solidarity and unity was a heavy demand to ask of a continent the size of Africa. Although the first half of the 1960s brimmed with limitless possibility and galvanizing talks, application of the policies set in place by the OAU was lukewarm at best. Conservative African states continued trading with Portugal and South Africa despite the embargo enforced by Algeria, and too many did not meet their mandatory financial contribution to the Liberation Committee. Meanwhile, liberation movements began to grow frustrated by conservative states’ efforts to constrain their activities and the Liberation Committee’s constant oversight. To some, the committee had become a stifling authority rather than the intended facilitating institution.

During a decade when a new international order was rapidly taking shape, African states’ had to prioritize consolidating their own statehood. Ghana’s idea of African federalism was shut down soon after being promoted — a weakening of the nation-state was not a price African countries were ready to pay to establish pan-African unity.

Simultaneously, African solidarity was used as a tool to serve national sovereignty. The FLN’s own colorful speeches about Algeria’s duty and responsibility toward colonized peoples conveniently fed into the country’s heroic myth of resistance, one forged in this period to heighten nationalism and delineate national identity. In 1963, Ben Bella summoned and used revolutionary pan-African fervor to cement its borders and discredit Morocco’s territorial claims after the monarchy launched a military offensive to gain control over a portion of Algeria’s Sahara region. To garner the African community’s overwhelming sympathy and support, the Algerian government made a case highlighting Morocco’s alliances with the United States and France. “This aggression is a battle between progressive republic and conservative monarchy, between revolution and imperialism,” proclaimed Ben Bella. Morocco’s King Hassan II was thus isolated and was one of the only African heads of state who did not attend the OAU’s festival in Addis Ababa.

Domestically, Ben Bella’s international appeal and Algeria’s leadership role in Africa came with dire consequences. Kabyle separatist movements paid the price of a policy that upheld a unified national identity at all costs and that refused to accept ethnic diversity and the culture of the Amazigh people indigenous to Algeria. Many Algerians criticized Ben Bella as a hubristic president who preferred fixing the world’s problems instead of focusing on Algeria’s grim socioeconomic realities.

Ben Bella’s dream of Algeria as the social leader of the “Third World” was brought to an abrupt end in June 1965 after his right-hand man, Houari Boumediene, orchestrated a military coup against him. The event triggered outrage across Africa. The heads of many states had woven threads of affinity with the outspoken and charismatic Ben Bella, and his ouster was regarded as an unforgivable betrayal. Following the coup, the ties that held radical African countries together unraveled and the diplomatic relations with revolutionary leaders soured.

Boumediene, in his first address to the nation, did attempt to reaffirm Algeria’s principle of unconditional support to revolutionaries: “The riches of the third world have served the interests of the rich nations. It is time for those nations to understand that economic colonialism — like political colonialism before it — must vanish.” Yet the personal relationships that Ben Bella had forged never fully transferred to Boumediene.

Throughout the 1960s, the “country of a million martyrs” proved its dedication to anticolonial solidarity by giving substance to African unity and support to liberation movements. But unifying the continent and holding it together proved to be an ambitious project that failed to take into account the inner divisions and contentions of Africa’s nascent independent states. By the beginning of the 1970s, domestic upheavals and the demands of a growing capitalist order got the better of Algeria’s revolutionary idealism and its left-leaning, radical foreign policy.

The last gasp of utopia in Algiers came with the 1969 Pan-African Cultural Festival, which brought together singers, artists and intellectuals from every African country and diaspora to perform in the name of African unity and revolutionary consciousness. There, dissidents and revolutionaries from the continent mingled with the likes of poet and author Maya Angelou and the Black Panther leader Stokely Carmichael in between sets by famous Tuareg musicians and Nina Simone.

On a hot July night, the South African singer Miriam Makeba took to the stage at the main stadium to perform some of her greatest anthems to freedom. Makeba, who had become stateless after South Africa revoked her citizenship for criticizing the regime and calling for an arms embargo at the U.N., had been granted Algerian citizenship several years earlier. “I am honored to have the nationality of a country that did so much for the liberation of Africa,” she said at the time.

As the heat settled and the crowd buzzed, Makeba raised the microphone to her lips; her strong, pure voice rang out as she sang, in the Algerian dialect, “Ana hourra fi al-Jazair, watani, umm al-shaheed” — “I am free in Algeria, my homeland, the mother of martyrs.”

Friday, January 03, 2025

At the heart of Algeria's concerns lies the presence of Russian paramilitary Wagner Group in Libya and Mali—which orchestrated attacks near its border.

Basma El Atti

Rabat

03 January, 2025

THE NEW ARAB

On the Ukraine front, Algiers voted at the UN to condemn Russia's

Algeria and Russia, long-time allies, are scrambling to patch up ties after months of tension over the Sahel, Libya, and military presence in North Africa.

Vyacheslav Volodin, Speaker of Russia's State Duma, is scheduled to visit Algiers in the coming weeks, marking his second trip to the North African nation in six months, reported local media.

The visit comes after Wagner Group airstrikes near Algeria's southern border with Mali in April, which prompted Algeria to ask for the UN intervention.

Last month, the Algeria-Russia Friendship Parliamentary Group met in Algiers to discuss strengthening relations. "Our interests in Sudan, Syria, and energy overlap, but we need clearer dialogue," said Abdelsalam Bachagha.

This diplomatic push follows months of tensions, fuelled by Russia's military footprint in North Africa.

At the heart of Algeria's concerns lies the Wagner Group. Russia's paramilitary forces have become entrenched in Mali after French troops were ousted in 2022.

Last February, Algeria's permanent representative to the UN, called for international accountability for the parties responsible for a deadly a drone attack that struck civilians in the Tinzaouatene region of Mali, just meters from the Mali-Algeria border.

It was reportedly orchestrated by Malian army and Wagner Group against Tuareg "terrorists."

The Tuareg are an ethnic group who have been fighting for independence since 2012.

Algeria has been vocal in opposing Moscow's attempts to brand Tuareg political movements as "terrorists" warning that further military action in Mali would only destabilise the region.

"We told our Russian friends that we will not accept the rebranding of Tuareg political movements as terrorist groups to justify further military action in northern Mali," Foreign Minister Ahmed Attaf told state media.

"Military solutions have always failed," added Attaf stating his country's expertise in the Sahel.

The North African state is also worried about the escalating situation in Libya, its eastern neighbour—another country where Wagner is reportedly active.

Moscow is backing Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar, whose forces have targeted Algerian border crossings.

The Wagner Group has had a foothold in Libya since 2018.

Miloud Ould Essedik, a political analyst, suggests the tensions go deeper. "In addition to supporting Tuareg, Algeria's role in supplying natural gas to Europe amid the Ukraine war has irked Moscow," he said.

Historical accords and discord between Algeria and Russia

Algeria and Russia's cooperation dates back to the Soviet era, when the USSR supported Algeria's independence movement and became a major arms supplier. In 2001, they signed a "Strategic Partnership Agreement," Russia's first of its kind in the region.

However, cooperation has not been without its challenges. Competition over gas exports to Europe has created friction, and Algeria's refusal to join a Russia-led gas cartel proves that the North African state wanted to maintain its own autonomy instead of committing to one camp.

The Algerian "neutrality" diplomacy has often clashed with Russia's.

In Libya, the two countries are on opposing sides: Russia backs Haftar, while Algeria supports the UN-backed government in Tripoli. On the Ukraine front, Algiers voted at the UN to condemn Russia's invasion, angering Moscow.

Despite this, Algiers has remained resolute in its support for Russia, resisting Western pressure to isolate Moscow.

Meanwhile, arms trade and defence collaboration continue to serve as the cornerstone of their bilateral relations.

The two countries are set to sign a proposed $12-$17 billion arms deal, including advanced fighters, submarines, and air defence systems, according to local media.

Despite these frictions, both sides seem determined to repair their relationship. Diplomatic visits have increased, with Russian officials—including Deputy Defence Minister Alexander Fomin and Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov—visiting Algiers last year. Algeria has reciprocated with high-level trips to Moscow.

The two nations have also created a formal mechanism for quarterly consultations involving officials from both sides on foreign policy, security, and defence.

Saturday, February 15, 2025

The conflict over Western Sahara is just one layer of the deep-rooted geopolitical battle for regional leadership between Morocco and Algeria.

2008 protest calling for the independence of the Western Sahara. Image credit Natalia de la Rubia via Shutterstock.

Too often, the Western Sahara conflict is viewed as the root cause of tensions between Algiers and Rabat. Analyzing Algeria-Morocco relations through the lens of this conflict is, however, not only incomplete but, more importantly, largely incorrect. As academic Yahia Zoubir underlines in his piece The Algerian-Moroccan Rivalry: Constructing the Imagined Enemy, “Algeria and Morocco’s strained relations are not solely the result of the Western Sahara conflict; they derive from a historical evolution of which the Western Sahara is only one aspect.” The dispute over the Western Sahara isn’t just about ownership of the land, rather, the conflict serves as a vessel for Morocco to gain regional hegemony at the cost of Algeria’s influence.

The nearly five-decades-long Western Sahara conflict between Morocco and the Polisario Front has contributed to the complicated relationship between Algiers and Rabat. However, this conflict is only the tip of the iceberg. In 1963, when the countries were then young independent states, the War of the Sands armed conflict resulted from Rabat’s claim that large portions of land, including Tindouf and Béchar regions in Western Algeria, belong to Morocco. In October of that year, with the backup of the United States, Morocco invaded Algeria over its irredentist territorial claims. For Morocco, borders inherited from the colonial era were artificial and had to be reviewed, while for Algeria, these borders must remain unchanged. This Moroccan attack, which took place just 12 years before the dispute over Western Sahara, has undeniably created an environment of profound mistrust between Rabat and Algiers, still tangible today. Since then, animosity from both Moroccan authorities and the Moroccan people towards Algeria’s authorities and Algerians has intensified.

These challenging relations didn’t stop Algeria and Morocco from reopening their borders to one another in 1988. However, the 1994 Marrakech bombing changed this. At the time, Moroccan authorities accused Algerian elements and intelligence services of being the masterminds of the attack. Morocco unilaterally imposed a visa for all Algerians who sought to enter Moroccan territory. In response, Algiers closed off the land border with Morocco, which hasn’t reopened since 1994.

More recently, in August 2021, Algeria ended its diplomatic relations with Morocco. Officials cited an array of reasons for this move, including accusations that Rabat spied on Algerian diplomats and politicians using Pegasus spyware, and a July push by the Moroccan ambassador to the United Nations for member states of the Non-Aligned Movement to recognize the independence of the Kabylie region of Algeria—a red line for Algiers. While such crises have popped up between the two neighbors, it has never led to direct conflict.

Indeed, contrary to popular belief, the difficult relations between Algiers and Rabat is mainly the result of unbridled ambition for regional leadership. As the pivotal state, Algeria is the natural regional leader par excellence, given its geostrategic position, economic weight, and military power. Therefore, Morocco understands that it can’t achieve its hegemonic goal without the annexation of Western Sahara. This dynamic, accompanied by a history of mistrust, has heightened tensions between the two countries.

Opposing political ideologies have also nurtured the rivalry between Morocco and Algeria. After gaining its independence in 1962, Algeria joined the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), while Morocco, despite also being a member of NAM, embraced the West. While these two neighbors have much in common—such as language, religion, and even family ties (via thousands of intermarriages)—relations have been complicated since their respective independences.

Besides being a close geostrategic ally of France and the United States, and thus benefiting from their unconditional support since its independence in 1956, Morocco enjoys a very positive reputation internationally due to a well-applied communication strategy and its strategic use of diplomatic and political maneuvers, especially on the Western Sahara dossier. In 2018 alone, Morocco reportedly spent $1.38 million in lobbying against Algeria in the United States. Rabat also hired a consulting firm for US$75,000 per month to lobby in favor of Morocco.

The worldwide scandal involving Morocco’s attempts to spy on foreign journalists, politicians, and members of civil society using the spying software system Pegasus, which was developed by the Israeli company NSO Group, further emphasizes the obsessive surveillance and regional ambition of the Moroccan regime, which has been dubbed a North Korea–like dictatorship. For the United Nations, such spying on politicians is illegal and undermines their rights.

As I clearly underline in my work “Morocco’s Intelligence Services and the Makhzen Surveillance System,” Morocco is often presented as a modernist and progressive country. Such an idealistic portrayal is, however, erroneous. Indeed, as Yom argues, the Moroccan Makhzen looks like a democratic reformer when compared to some other states of the MENA region and the Gulf monarchies—which include some of the world’s most closed and coercive dictatorships. When plucked from this context and analyzed on its own terms, however, the trajectory of Morocco’s Alawite Dynasty does not look nearly so promising.

Moroccan media regularly portrays Algeria in a negative light on behalf of the Moroccan elite, and a large number of academics simply mimic the negative representation of Algeria that the media and decision-makers put forward. Moreover, in the event of a dispute, it is often the case that “Algeria ends up paying the cost diplomatically as all the [international] sympathy tends to be concentrated on Morocco.”

This attitude is even more pronounced in France, where the profound and visceral hostility of a large fringe of the political elite who have yet to accept Algeria’s independence—left and right alike—towards Algeria contributes to this negative image of Algeria and Algerians. Moreover, as the former French Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin underlines, Algeria is too often the scapegoat of France’s internal political illness. It is, therefore, through this Hegelian strategy, whereby a constantly repeated lie becomes the truth, that observers analyze the relations between Morocco and Algeria.

However, every communication strategy has its limits. In May 2021, following the Pegasus scandal, Morocco’s reputation was shaken by editorials from the Spanish El Mundo and the French Le Monde, characterizing Moroccan authorities as cynical and asserting that “it was time for Western chancelleries to review their naivety vis à vis Morocco.” As early as 2001, José Bono, the former defense minister of Spain, declared that Morocco was not a democracy but a covert dictatorship, a country dominated by a mafia.

The French recognition of Rabat’s sovereignty over the occupied Western Sahara territory may give more impetus to Rabat. But it will clearly not alter its rivalry (and animosity) towards Algeria. Indeed, due to the opposing nature of the two countries, compounded by a profound mistrust of each other and, more importantly, their regional leadership ambition, whatever the outcome of the Western Sahara conflict will eventually be, the battle for regional leadership will remain as fierce as ever.

Regarding the occupied Western Sahara, and regardless of Rabat’s external support, it is paramount to remember that Morocco’s illegal occupation of Western Sahara—the last colonized territory in Africa—is in direct violation of international law. In 1963, the UN included Western Sahara in a list of territories that sought self-determination. The notion of self-determination was enshrined in the UN Charter and is supported by UN Resolution 1514, which stipulates that “all people have the right to self-determination.” This was further supported by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in a ruling on October 16, 1975, declaring that Western Sahara was not “land belonging to no-one” (terra nullius) at the time of its colonization by Spain. The ICJ judgment, therefore, declared that Morocco had no valid claim on Western Sahara based on any historic title and that, even if it had, contemporary international law accorded priority to the Sahrawi right to self-determination.

Meanwhile, the security situation in the Maghreb remains worrying, and Morocco’s fait accompli annexation of Western Sahara will only fuel deeper instability. Without a fair and honest solution for the Sahrawis through a referendum, instability will only grow in North Africa, further destabilizing the neighboring Sahel region. If a dreadful scenario results from this instability, French authorities—and all their blind—would surely be ill-advised to intervene in any way.

Abdelkader Abderrahmane is a policy adviser on peace and security in North Africa and the Sahel. He is the author of “Morocco's Intelligence Services and the Makhzen Surveillance System.”